Mark Elliot Zuckerberg (/ˈzʌkərbɜːrɡ/; born May 14, 1984) is an American businessman who co-founded the social media service Facebook and its parent company Meta Platforms, of which he is the chairman, chief executive officer, and controlling shareholder. Zuckerberg has been the subject of multiple lawsuits regarding the creation and ownership of the website as well as issues such as user privacy.

Mark Zuckerberg | |

|---|---|

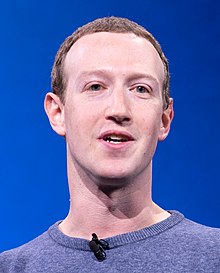

Zuckerberg in 2019 | |

| Born | Mark Elliot Zuckerberg May 14, 1984 White Plains, New York, U.S. |

| Other names | Zuck |

| Education | Harvard University (dropped out) |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 2004–present |

| Title |

|

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives |

|

| Website | facebook |

| Signature | |

Zuckerberg briefly attended Harvard College, where he launched Facebook in February 2004 with his roommates Eduardo Saverin, Andrew McCollum, Dustin Moskovitz and Chris Hughes. Zuckerberg took the company public in May 2012 with majority shares. He became the world's youngest self-made billionaire in 2008, at age 23, and has consistently ranked among the world's wealthiest individuals. He has also used his funds to organize multiple donations, including the establishment of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

A film depicting Zuckerberg's early career, legal troubles and initial success with Facebook, The Social Network, was released in 2010 and won multiple Academy Awards. His prominence and fast rise in the technology industry has prompted political and legal attention.

Early life and education

Mark Elliot Zuckerberg was born on May 14, 1984, in White Plains, New York to psychiatrist Karen (née Kempner) and dentist Edward Zuckerberg.[1][2] He and his three sisters (Arielle, Randi, and Donna) were raised in a Reform Jewish household[3] in Dobbs Ferry, New York.[4] His great-grandparents were emigrants from Austria, Germany, and Poland.[5] Zuckerberg initially attended Ardsley High School before transferring to Phillips Exeter Academy. He was captain of the fencing team.[6][7]

Software development

Early years

Zuckerberg had learnt computer programming while young. At about the age of eleven, he created "ZuckNet", a program that allowed computers at the family home and his father's dental office to communicate with each other. [8] During Zuckerberg's high-school years, he worked to build a music player called the Synapse Media Player. The device used machine learning to learn the user's listening habits, which was posted to Slashdot[9] and received a rating of 3 out of 5 from PC Magazine.[10] The New Yorker once said of Zuckerberg, "some kids played computer games. Mark created them."[4] While still in high school, he attended Mercy College taking a graduate computer course on Thursday evenings.[4]

College years

The New Yorker noted that by the time Zuckerberg began classes at Harvard in 2002, he had already achieved a "reputation as a programming prodigy".[4] He studied psychology and computer science,[11] resided in Kirkland House,[12] and belonged to Alpha Epsilon Pi.[4] In his second year, he wrote a program that he called CourseMatch, which allowed users to make class selection decisions based on the choices of other students and help them form study groups.[13] Later, he created a different program he initially called Facemash that let students select the best-looking person from a choice of photos. Arie Hasit, Zuckerberg's roommate at the time, explained:

We had books called "Face Books", which included the names and pictures of everyone who lived in the student dorms. At first, he built a site and placed two pictures or pictures of two males and two females. Visitors to the site had to choose who was "hotter" and according to the votes there would be a ranking.[14]

The site went up over a weekend, but by Monday morning, the college shut it down, because its popularity had overwhelmed one of Harvard's network switches preventing students from accessing the Internet.[15] In addition, many students complained that their photos were being used without permission. Zuckerberg apologized publicly, and the student paper ran articles stating that his site was "completely improper".[14]

Career

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| "Mark Zuckerberg's career in 90 seconds | Tech Gurus" via The Daily Telegraph[16] |

In January 2004, Zuckerberg began writing code for a new website.[17] On February 4, 2004, Zuckerberg launched "Thefacebook", originally located at thefacebook.com, in partnership with his roommates Eduardo Saverin, Andrew McCollum, Dustin Moskovitz, and Chris Hughes.[18][19] An earlier inspiration for Facebook may have come from Phillips Exeter Academy, the prep school from which Zuckerberg graduated in 2002. It published its own student directory, "The Photo Address Book", which students referred to as "The Facebook". Such photo directories were an important part of the student social experience at many private schools. With them, students were able to list attributes such as their class years, their friends, and their telephone numbers.[19]

Six days after the site launched, three Harvard seniors, Cameron Winklevoss, Tyler Winklevoss, and Divya Narendra, accused Zuckerberg of intentionally misleading them into believing that he would help them build a social network called HarvardConnection.com, when he was using their ideas to build a competing product.[20] The three complained to The Harvard Crimson, and the newspaper began an investigation in response. While Zuckerberg tried to convince the editors not to run the story,[21] he also broke into two of the editors' email accounts—for which he made use of their private login data logs from TheFacebook.[22][23]

Following the official launch of the Facebook social media platform, the three filed a lawsuit against Zuckerberg that resulted in a settlement.[24] The agreed settlement was for 1.2 million Facebook shares and $20 million in cash.[25]

Zuckerberg's Facebook started off as just a "Harvard thing" until he decided to spread it to other schools, enlisting the help of roommate and co-founder Dustin Moskovitz.[26] They began with Columbia University, New York University, Stanford University, Dartmouth College, Cornell University, University of Pennsylvania, Brown University, and Yale University.[27]

Zuckerberg dropped out of Harvard in his sophomore year in order to complete the project.[28] Zuckerberg, Moskovitz and the other co-founders moved to Palo Alto, California, where they leased a small house that served as an office. Over the summer, Zuckerberg met Peter Thiel, who invested in his company. They got their first office in mid-2004. According to Zuckerberg, the group planned to return to Harvard, but eventually decided to remain in California, where Zuckerberg appreciated the "mythical place" of Silicon Valley, the center of computer technology in California.[29][30] They had already turned down offers by major corporations to buy the company. In an interview in 2007, Zuckerberg explained his reasoning: "It's not because of the amount of money. For me and my colleagues, the most important thing is that we create an open information flow for people. Having media corporations owned by conglomerates is just not an attractive idea to me."[31] The same year, speaking at Y Combinator's Startup School course at Stanford University, Zuckerberg made a controversial assertion that "young people are just smarter" and that other entrepreneurs should bias towards hiring young people.[32]

He restated these goals to Wired magazine in 2010, "The thing I really care about is the mission, making the world open."[33] Earlier, in April 2009, Zuckerberg had sought the advice of former Netscape CFO Peter Currie regarding financing strategies for Facebook.[34] On July 21, 2010, Zuckerberg reported that Facebook had reached the 500-million-user mark.[35] When asked whether Facebook could earn more income from advertising as a result of its phenomenal growth, he explained:

I guess we could ... If you look at how much of our page is taken up with ads compared to the average search query. The average for us is a little less than 10 percent of the pages and the average for search is about 20 percent taken up with ads ... That's the simplest thing we could do. But we aren't like that. We make enough money. Right, I mean, we are keeping things running; we are growing at the rate we want to.[33]

In 2010, Steven Levy, who wrote the 1984 book Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution, wrote that Zuckerberg "clearly thinks of himself as a hacker". Zuckerberg said that "it's OK to break things" "to make them better".[36][37] Facebook instituted "hackathons" held every six to eight weeks where participants would have one night to conceive of and complete a project.[36] The company provided music, food, and beer at the hackathons, and many Facebook staff members, including Zuckerberg, regularly attended.[37] "The idea is that you can build something really good in a night", Zuckerberg told Levy. "And that's part of the personality of Facebook now ... It's definitely very core to my personality."[36]

In 2007, Zuckerberg was added to MIT Technology Review's TR35 list as one of the top 35 innovators in the world under the age of 35.[38] Vanity Fair magazine named Zuckerberg number 1 on its 2010 list of the Top 100 "most influential people of the Information Age".[39] Zuckerberg ranked number 23 on the Vanity Fair 100 list in 2009.[40] In 2010, Zuckerberg was chosen as number 16 in New Statesman's annual survey of the world's 50 most influential figures.[41]

In a 2011 interview with PBS shortly after the death of Steve Jobs, Zuckerberg said that Jobs had advised him on how to create a management team at Facebook that was "focused on building as high quality and good things as you are".[42]

On October 1, 2012, Zuckerberg met with then Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev in Moscow to stimulate social media innovation in Russia and to boost Facebook's position in the Russian market.[43][44] Russia's communications minister tweeted that Medvedev persuaded Zuckerberg to open a research center in Moscow instead of trying to lure away Russian programmers. In 2012, Facebook had roughly 9 million users in Russia, while domestic clone VK had around 34 million.[45][46] Rebecca Van Dyck, Facebook's head of consumer marketing, said that 85 million American Facebook users were exposed to the first day of the Home promotional campaign on April 6, 2013.[47]

On August 19, 2013, The Washington Post reported that Zuckerberg's Facebook profile was hacked by an unemployed web developer.[48]

At the 2013 TechCrunch Disrupt conference, held in September, Zuckerberg stated that he was working towards registering the 5 billion people who were not connected to the Internet as of the conference on Facebook. Zuckerberg then explained that this is intertwined with the aim of the Internet.org project, whereby Facebook, with the support of other technology companies, seeks to increase the number of people connected to the internet.[49][50]

Zuckerberg was the keynote speaker at the 2014 Mobile World Congress (MWC), held in Barcelona, Spain, in March 2014, which was attended by 75,000 delegates. Various media sources highlighted the connection between Facebook's focus on mobile technology and Zuckerberg's speech, stating that mobile represents the future of the company.[51] Zuckerberg's speech expands upon the goal that he raised at the TechCrunch conference in September 2013, whereby he is working towards expanding Internet coverage into developing countries.[52]

Alongside other American technology figures such as Jeff Bezos and Tim Cook, Zuckerberg hosted visiting Chinese politician Lu Wei, known as the "Internet czar" for his influence in the enforcement of China's online policy, at Facebook's headquarters on December 8, 2014. The meeting occurred after Zuckerberg participated in a Q&A session at Tsinghua University in Beijing, China, on October 23, 2014, where he conversed in Mandarin Chinese; although Facebook is banned in China, Zuckerberg is highly regarded among the people and was at the university to help fuel the nation's burgeoning entrepreneur sector.[53]

Zuckerberg fielded questions during a live Q&A session at the company's headquarters in Menlo Park on December 11, 2014. The founder and CEO explained that he does not believe Facebook is a waste of time, because it facilitates social engagement, and participating in a public session was so that he could "learn how to better serve the community".[54][55]

Zuckerberg receives a one-dollar salary as CEO of Facebook.[56] In June 2016, Business Insider named Zuckerberg one of the "Top 10 Business Visionaries Creating Value for the World" along with Elon Musk and Sal Khan, due to the fact that he and his wife "pledged to give away 99% of their wealth-then estimated at $55.0 billion".[57]

On May 25, 2017, at Harvard's 366th commencement day, Zuckerberg, after giving a commencement speech,[58] received an honorary degree from Harvard.[59][60]

In January 2019, Zuckerberg laid plans to integrate an end-to-end encrypted system for three major social media platforms, including Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp.[61] On August 14, 2020, Facebook integrated the chat systems for Instagram and Messenger on both iOS and Android devices. The update encouraged cross-communication between Instagram and Facebook users.[62]

Other projects

A month after Zuckerberg launched Facebook in February 2004, i2hub, another campus-only service, created by Wayne Chang and focusing on peer-to-peer file sharing, was launched. At the time, both i2hub and Facebook were gaining the attention of the press and growing rapidly in users and publicity. In August 2004, Zuckerberg, Andrew McCollum, Adam D'Angelo, and Sean Parker launched a competing peer-to-peer file sharing service called Wirehog, a precursor to Facebook Platform applications, which was launched in 2007.[63][64][65]

In 2013, Zuckerberg launched Internet.org, which he described as an initiative to provide Internet access to the five billion people without it as of the launch date. The project faced significant opposition in India, where activists said its limited internet ran counter to the principle of net neutrality; Zuckerberg responded by saying that a limited internet was better than no internet. Internet.org was shut down in India in February 2016, although Zuckerberg later met with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to discuss further possibilities.[66][67]

Zuckerberg is a board member of the solar sail spacecraft development project Breakthrough Starshot, which he co-founded with Yuri Milner and Stephen Hawking in 2016.[68]

Legal trouble

ConnectU lawsuits

Harvard students Cameron Winklevoss, Tyler Winklevoss, and Divya Narendra accused Zuckerberg of intentionally making them believe he would help them build a social network called HarvardConnection.com (later called ConnectU).[20] They filed a lawsuit in 2004; it was dismissed on a technicality on March 28, 2007. It was refiled soon thereafter in a federal court in Boston. Facebook countersued in regards to Social Butterfly, a project put out by The Winklevoss Chang Group, an alleged partnership between ConnectU and i2hub. On June 25, 2008, the case settled and Facebook agreed to transfer over 1.2 million common shares and pay $20 million in cash.[69]

In November 2007, confidential court documents were posted on the website of 02138, a magazine that catered to Harvard alumni. They included Zuckerberg's Social Security number, his parents' home address, and his girlfriend's address. Although Facebook filed to have the documents removed, the judge ruled in favor of 02138.[70]

Eduardo Saverin

In 2005, Facebook co-founder Eduardo Saverin filed a lawsuit against Zuckerberg and Facebook, alleging that Zuckerberg had illegally spent Saverin's money on personal expenses. The lawsuit was settled out of court and, although terms of the settlement were sealed, the company affirmed Saverin's title as co-founder of Facebook, and Saverin agreed to stop talking to the press.[71][72]

Pakistan criminal investigation

In June 2010, then Pakistani Deputy Attorney General Muhammad Azhar Sidiqque launched a criminal investigation into Zuckerberg and Facebook co-founders Dustin Moskovitz and Chris Hughes after a "Draw Muhammad" contest was hosted on Facebook. The investigation also named the anonymous German woman who created the contest. Sidiqque asked the country's police to contact Interpol to have Zuckerberg and the three others arrested for blasphemy. On May 19, 2010, Facebook's website was temporarily blocked in Pakistan until Facebook removed the contest from its website at the end of May. Sidiqque also asked its UN representative to raise the issue with the United Nations General Assembly.[73][74]

Paul Ceglia

In June 2010, Paul Ceglia, the owner of a wood pellet fuel company in Allegany County, upstate New York, filed suit against Zuckerberg, claiming 84 percent ownership of Facebook and seeking monetary damages. According to Ceglia, he and Zuckerberg signed a contract on April 28, 2003, that an initial fee of $1,000 entitled Ceglia to 50% of the website's revenue, as well as an additional 1% interest in the business per day after January 1, 2004, until website completion. Zuckerberg was developing other projects at the time, among which was Facemash, the predecessor to Facebook, but did not register the domain name thefacebook.com until January 1, 2004. The Facebook management dismissed the lawsuit as "completely frivolous". Facebook spokesman Barry Schnitt told a reporter that Ceglia's counsel had unsuccessfully sought an out-of-court settlement.[75][76]

On October 26, 2012, federal authorities arrested Ceglia, charging him with mail and wire fraud and of "tampering with, destroying and fabricating evidence in a scheme to defraud the Facebook founder of billions of dollars". Ceglia is accused of fabricating emails to make it appear that he and Zuckerberg discussed details about an early version of Facebook, although after examining their emails, investigators found there was no mention of Facebook in them.[77] Some law firms withdrew from the case before it was initiated and others after Ceglia's arrest.[78][79]

Hawaiian land ownership

In 2014 Zuckerberg purchased 700 acres of land on the Hawaiian island of Kauaʻi. In January 2017, Zuckerberg filed eight "quiet title and partition" lawsuits against hundreds of native Hawaiians to claim small tracts of land that they owned within his acreage.[80] Zuckerberg responded to criticisms in a Facebook post, stating that the lawsuits were a good faith effort to pay the partial owners of the land their "fair share".[80] When he learned that Hawaiian land ownership law differs from that of the other 49 states, he dropped the lawsuits. Zuckerberg stated that he regretted not taking the time to understand the process and its history before moving ahead.[81][82]

Testimony before U.S. Congress

On April 10 and 11, 2018, Zuckerberg testified before the United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation regarding the usage of personal data by Facebook in relation to the Facebook–Cambridge Analytica data scandal.[83] [84] He called the whole affair a breach of trust between Aleksandr Kogan, Cambridge Analytica, and Facebook.[85] Zuckerberg refused requests to appear to give evidence on the matter to a Parliamentary committee in the United Kingdom.[86]

On October 1, 2020, the US Senate Commerce Committee unanimously voted to issue subpoenas to the CEOs of three top tech firms, including Zuckerberg, Google's Sundar Pichai and Twitter's Jack Dorsey. The subpoenas aimed to force the CEOs to testify about the legal immunity the law affords tech platforms under Section 230 of the Communications Act of 1934. US Republicans argued that the law unduly protected social media companies against allegations of anti-conservative censorship.[87]

On March 25, 2021, Zuckerberg testified before the House Energy and Commerce Committee regarding Facebook's role in the spread of misinformation and hate speech on the platform. During the hearing, he was questioned about Facebook's handling of user data, its role in the January 6, 2021, attack on the US Capitol Building, and its efforts to combat misinformation and hate speech. Zuckerberg acknowledged that Facebook had a responsibility to address these issues and outlined the steps that the company is taking to improve its policies and practices. The hearing was part of a broader effort by Congress to hold tech companies accountable for their role in shaping public discourse and protecting user privacy.[88]

In a January 2024 Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on child safety and social media platforms, Zuckerberg, along with other tech CEOs, were questioned about their companies' practices. During the hearing, he apologized to the families of children who were victims of online abuse and harm.[89][90]

Meta's proposal

Court documents allege that Zuckerberg personally rejected Meta's proposals to improve teenagers' mental health. He consistently opposed efforts to enhance well-being on Facebook and Instagram, overriding senior executives such as Instagram head Adam Mosseri and Global Affairs President Nick Clegg, as revealed in an ongoing lawsuit. Internal communications disclosed in the Massachusetts-initiated legal action depict Zuckerberg's resistance to better protect over 30 million teens on Instagram in the U.S., highlighting his substantial influence on Meta's decisions impacting billions of users. These documents also shed light on occasional tensions between Zuckerberg and other Meta officials advocating for improved user well-being.[91]

Depictions in media

The Social Network

A movie based on Zuckerberg and the founding years of Facebook, The Social Network, was released on October 1, 2010, starring Jesse Eisenberg as Zuckerberg. After Zuckerberg was told about the film, he responded, "I just wished that nobody made a movie of me while I was still alive."[92] Also, after the film's script was leaked on the Internet and it was apparent that the film would not portray Zuckerberg in a wholly positive light, he stated that he wanted to establish himself as a "good guy".[93] The film is based on the book The Accidental Billionaires by Ben Mezrich, which the book's publicist once described as "big juicy fun" rather than "reportage".[94] The film's screenwriter Aaron Sorkin told New York magazine, "I don't want my fidelity to be the truth; I want it to be storytelling", adding, "What is the big deal about accuracy purely for accuracy's sake, and can we not have the true be the enemy of the good?".[95]

Upon winning the Golden Globe Award for Best Picture on January 16, 2011, producer Scott Rudin thanked Facebook and Zuckerberg "for his willingness to allow us to use his life and work as a metaphor through which to tell a story about communication and the way we relate to each other".[96] Sorkin, who won for Best Screenplay, retracted some of the impressions given in his script:[97]

- I wanted to say to Mark Zuckerberg tonight, if you're watching, Rooney Mara's character makes a prediction at the beginning of the movie. She was wrong. You turned out to be a great entrepreneur, a visionary, and an incredible altruist.

In January 2011, Zuckerberg made a surprise guest appearance on Saturday Night Live, which was hosted by Jesse Eisenberg. They both said it was the first time they had met.[98] Eisenberg asked Zuckerberg, who had been critical of his portrayal by the film, what he thought of the movie. Zuckerberg replied, "It was interesting."[99] In a subsequent interview about their meeting, Eisenberg explained that he was "nervous to meet him, because I had spent now, a year and a half thinking about him ...". He added, "Mark has been so gracious about something that's really so uncomfortable ... The fact that he would do SNL and make fun of the situation is so sweet and so generous. It's the best possible way to handle something that, I think, could otherwise be very uncomfortable."[100][101]

Disputed accuracy

According to David Kirkpatrick, former technology editor at Fortune magazine and author of The Facebook Effect: The Inside Story of the Company that is Connecting the World (2011),[102] "the film is only 40% true ... he is not snide and sarcastic in a cruel way, the way Zuckerberg is played in the movie." He says that "a lot of the factual incidents are accurate, but many are distorted and the overall impression is false", and concludes that primarily "his motivations were to try and come up with a new way to share information on the Internet".[103]

Although the film portrayed Zuckerberg's creation of Facebook in order to elevate his stature after not getting into any of the elite final clubs at Harvard, Zuckerberg stated that he had no interest in joining the clubs.[4] Kirkpatrick agreed that the impression implied by the film is "false". Karel Baloun, a former senior engineer at Facebook, noted that the "image of Zuckerberg as a socially inept nerd is overstated ... It is fiction ...". He likewise dismissed the film's assertion that he "would deliberately betray a friend".[103]

Other depictions

Zuckerberg voiced himself on an episode of The Simpsons titled "Loan-a Lisa", which first aired on October 3, 2010. In the episode, Lisa Simpson and her friend Nelson encounter Zuckerberg at an entrepreneurs' convention. Zuckerberg tells Lisa that she does not need to graduate from college to be wildly successful, referencing Bill Gates and Richard Branson as examples.[104] On October 9, 2010, Saturday Night Live lampooned Zuckerberg and Facebook.[105] Andy Samberg portrayed the role of Zuckerberg. Zuckerberg himself was reported to have been amused, "I thought this was funny."[106]

Stephen Colbert awarded a "Medal of Fear" to Zuckerberg at the Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear on October 30, 2010, "because he values his privacy much more than he values yours".[107] Zuckerberg appeared in the climax of 2013 documentary film Terms and Conditions May Apply.[108][109][110] The South Park episode "Franchise Prequel" mocked him. According to CNET, he was portrayed as "a rosy-cheeked bully nerd who utters strange noises, makes peculiar kung fu gestures and turns up wherever he likes in people's houses".[111]

Donations and Chan Zuckerberg Initiative

Zuckerberg founded the Startup:Education foundation.[112] It was reported in September 2010 that he had donated $100 million to Newark Public Schools, the public school system of Newark, New Jersey.[113][114] Critics noted the timing of the donation as being close to the release of The Social Network, which painted a somewhat negative portrait of Zuckerberg.[115] Zuckerberg responded to the criticism, saying, "The thing that I was most sensitive about with the movie timing was, I didn't want the press about The Social Network movie to get conflated with the Newark project. I was thinking about doing this anonymously just so that the two things could be kept separate."[116] Newark Mayor Cory Booker stated that he and New Jersey Governor Chris Christie had to convince Zuckerberg's team not to make the donation anonymously.[116] The money was largely wasted, according to journalist Dale Russakoff.[117][118]

In 2010, Zuckerberg, Bill Gates, and investor Warren Buffett signed The Giving Pledge, in which they said they would donate to charity at least half of their wealth over the course of time, and invited others among the wealthy to donate 50 percent or more of their wealth to charity.[119] In December 2012, Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan said that over the course of their lives they would give the majority of their wealth to "advancing human potential and promoting equality" in the spirit of The Giving Pledge.[120][121]

In December 2013, Zuckerberg announced a donation of 18 million Facebook shares to the Silicon Valley Community Foundation, to be executed by the end of the month—based on Facebook's valuation as of then, the shares totaled $990 million in value. Later that month, the donation was recognized as the largest charitable gift on public record for that year.[122] The Chronicle of Philanthropy placed Zuckerberg and his wife at the top of the magazine's annual list of 50 most generous Americans for 2013, having donated roughly $1 billion to charity.[123]

In October 2014, Zuckerberg and his wife donated $25 million to combat the Ebola virus disease, specifically the West African Ebola virus epidemic.[124][125] The couple endowed the foundation of the San Francisco General Hospital in February 2015 with $75 million, which was the biggest individual donation to a U.S. public hospital. The hospital honored them by renaming itself as The Priscilla Chan and Mark Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center. Later in 2020, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed a near-unanimous, non-binding measure condemning the renaming, citing concerns that a public hospital should not be named after an individual whose social media platform is accused of "endangering public health, spreading misinformation, and violating privacy".[126] On December 1, 2015, the couple pledged to transfer 99% of their Facebook shares, then valued at $45 billion, to the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI).[127] The funds would not be transferred immediately, but over the course of their lives.[128] Instead of forming a charitable corporation to donate the value of the stock to, as Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, Larry Page, Sergey Brin and other billionaires have done, Zuckerberg and Chan chose to use the structure of a limited liability company (LLC). Some journalists and academics have said the CZI conducts philanthrocapitalism.[129][130][131]

In 2016, CZI gave $600 million to create the tax-exempt charity Chan Zuckerberg Biohub, a collaborative research space in San Francisco's Mission Bay district near the University of California, San Francisco, with the intent to foster interaction and collaboration between scientists at UCSF, University of California, Berkeley, and Stanford University. Intellectual property generated would be jointly owned by Biohub and the discoverer's home institution. Unlike foundations such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which open up all research funded to unrestricted access and reuse by the public, Biohub retained the right to commercialize any research it funds. Inventors will have the option of making their discoveries open-source, with permission from Biohub.[132][133][134] To increase access to scientific research and promote open science, CZ Biohub requires its investigators and staff scientists to publish submitted manuscripts and related data on preprints servers such as bioRxiv.[135][136]

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, Zuckerberg donated $25 million to a Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation-backed accelerator that is searching for treatments for the disease.[137] He also announced $25 million in grants to support local journalism that was impacted by the pandemic and $75 million in advertisement purchases in local newspapers by Facebook, Inc., where Facebook would market itself.[138]

Politics

In 2002, Zuckerberg registered to vote in Westchester County, New York, where he grew up, but did not cast a ballot until November 2008. Then Santa Clara County Registrar of Voters Spokeswoman, Elma Rosas, told Bloomberg that Zuckerberg is listed as "no preference" on voter rolls, and he voted in at least two of the past three general elections, in 2008 and 2012.[139][140]

Zuckerberg has never revealed his own political affiliation or voting history. In February 2013, Zuckerberg hosted his first ever fundraising event for then New Jersey Governor Chris Christie. His particular interest on this occasion was education reform, and Christie's education reform work focused on teachers unions and the expansion of charter schools.[141][142] Later that year, Zuckerberg hosted a campaign fundraiser for then Newark mayor Cory Booker, who was running in the 2013 New Jersey special Senate election.[143] In September 2010, with the support of Governor Chris Christie, Booker obtained a US$100 million pledge from Zuckerberg to Newark Public Schools.[144] In December 2012, Zuckerberg donated 18 million shares to the Silicon Valley Community Foundation, a community organization that includes education in its list of grant-making areas.[145][146]

On April 11, 2013, Zuckerberg led the launch of a 501(c)(4) lobbying group called FWD.us. The founders and contributors to the group were primarily Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and investors, and its president was Joe Green, a close friend of Zuckerberg.[147][148] The goals of the group include immigration reform, improving the state of education in the United States, and enabling more technological breakthroughs that benefit the public,[149][150] yet it has also been criticized for financing ads advocating a variety of oil and gas development initiatives, including drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and the Keystone XL pipeline.[151] In 2013, numerous liberal and progressive groups, such as The League of Conservation Voters, MoveOn.org, the Sierra Club, Democracy for America, CREDO, Daily Kos, 350.org, and Presente and Progressives United agreed to either not buy or pull their Facebook ads for at least two weeks, in protest of ads funded by FWD.us that were in support of oil drilling and the Keystone XL pipeline, and in opposition to Obamacare among Republican United States senators who back immigration reform.[152]

A media report on June 20, 2013, revealed that Zuckerberg actively engaged with Facebook users on his own profile page after the online publication of a FWD.us video. In response to a claim that the FWD.us organization is "just about tech wanting to hire more people", the Internet entrepreneur replied, "The bigger problem we're trying to address is ensuring the 11 million undocumented folks living in this country now and similar folks in the future are treated fairly."[153]

In June 2013, Zuckerberg joined Facebook employees in a company float as part of the annual San Francisco Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Pride Celebration. The company first participated in the event in 2011, with 70 employees, and this number increased to 700 for the 2013 march. The 2013 pride celebration was especially significant, as it followed a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that deemed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) unconstitutional.[154][155]

When questioned about the mid-2013 PRISM scandal at the TechCrunch Disrupt conference in September 2013, Zuckerberg stated that the U.S. government "blew it". He further explained that the government performed poorly in regard to the protection of the freedoms of its citizens, the economy, and companies.[49]

Zuckerberg placed a statement on his Facebook wall on December 9, 2015, which said that he wants "to add my voice in support of Muslims in our community and around the world" in response to the aftermath of the November 2015 Paris attacks and the 2015 San Bernardino attack.[156][157][158][159] The statement also said that Muslims are "always welcome" on Facebook, and that his position was a result of the fact that, "as a Jew, my parents taught me that we must stand up against attacks on all communities."[160][161]

On February 24, 2016, Zuckerberg sent out a company-wide internal memo to employees formally rebuking employees who had crossed out handwritten "Black Lives Matter" phrases on the company walls and had written "All Lives Matter" in their place. Facebook allows employees to free-write thoughts and phrases on company walls. The memo was then leaked by several employees. As Zuckerberg had previously condemned this practice at previous company meetings, and other similar requests had been issued by other leaders at Facebook, Zuckerberg wrote in the memo that he would now consider this overwriting practice not only disrespectful, but "malicious as well". According to Zuckerberg's memo, "Black Lives Matter doesn't mean other lives don't – it's simply asking that the black community also achieves the justice they deserve." The memo also noted that the act of crossing something out in itself "means silencing speech, or that one person's speech is more important than another's". Zuckerberg also said in the memo that he would be launching investigations into the incidents.[162][163][164] The New York Daily News interviewed Facebook employees who commented anonymously that, "Zuckerberg was genuinely angry about the incident and it really encouraged staff that Zuckerberg showed a clear understanding of why the phrase 'Black Lives Matter' must exist, as well as why writing through it is a form of harassment and erasure."[162]

In January 2017, Zuckerberg criticized Donald Trump's executive order to severely limit immigrants and refugees from some countries.[165] He also funded a state-level ballot initiative for the 2020 general election that would raise taxes by altering California's Proposition 13 to require the tax assessment of commercial and industrial properties in the state at market rate.[166]

Especially in his twenties, Zuckerberg had financially supported various progressive causes such as immigration reform and social justice. At least among Republicans, he was generally seen as pro liberal. In a August 2024 letter to the House Judiciary Committee however, Zuckerberg stated he regretted not doing more to resist pressure from the Biden administration to censure content related to COVID-19. He also noted he no longer intends to donate towards election infrastructure; Republicans had seen those contributions as non neutral, labelling them "Zuckerbucks". As of 2024, Zuckerberg has been discouraging employee activism at Facebook, and accordingly to the New York Times, had non-publicly described his politics as leaning towards libertarianism or classical liberalism.[167][168][169][170]

Personal life

Marriage and children

Zuckerberg met fellow Harvard student Priscilla Chan at a frat party during his sophomore year with whom he began dating in 2003.[171] In September 2010, Chan, who was a medical student at the University of California, San Francisco at the time,[172] moved into his rented house in Palo Alto, California.[173][174] They married on May 19, 2012, in the grounds of his mansion in an event that also celebrated her graduation from medical school.[175][176] Zuckerberg revealed on July 31, 2015, that they were expecting a baby girl and that Chan had previously experienced three miscarriages.[177] Their daughter, Maxima Chan Zuckerberg, was born on December 1, 2015.[178] They announced in a Chinese New Year video that their daughter's Chinese name is Chen Mingyu (Chinese: 陈明宇).[179] Their second daughter, August, was born in August 2017.[180] Zuckerberg and his wife welcomed their third daughter Aurelia on March 24, 2023, and announced the news across his social media pages.[181] The couple also have a Puli dog named Beast,[182] who has over two million followers on Facebook.[183] Zuckerberg commissioned the visual artist Daniel Arsham to build a 7-foot-tall sculpture of his wife, which was unveiled in 2024.[184]

Recognition

Time named Zuckerberg one of the most influential people in the world in 2008, 2011, 2016, and 2019, and nominated him as a finalist several other times. He was named the Time Person of the Year in 2010, the same year when Facebook eclipsed more than half a billion users.[185] He was also included in the Time 100 AI list in 2024.[186] In December 2016, Zuckerberg was ranked tenth on the Forbes list of the World's Most Powerful People.[187] In the Forbes 400 list of wealthiest Americans in 2023, he was ranked eighth with a personal wealth of $106 billion.[188] As of October 2024[update], Zuckerberg's net worth was estimated at $202 billion by Forbes, making him the fourth richest person in the world.[189]

Religious beliefs and other interests

Raised as a Reform Jew, Zuckerberg later identified as an atheist. However, he said in 2016 that, "I went through a period where I questioned things, but now I believe religion is very important."[6][190][191] In 2017, he and his wife began a nationwide tour "to visit every state in the union and learn more about a sliver of the nearly two billion people who regularly use the social network". He met with farmers and business owners, and spoke at Mother Emanuel, where a shooting took place in 2015.[192][193]

In 2022, Zuckerberg took up training in both mixed martial arts (MMA) and Brazilian jiu-jitsu (BJJ), and has been open about his love for the two sports.[194] He competed in a BJJ tournament on May 6, 2023, and won both a silver and gold medal in gi and no gi, competing at white belt.[195] In July 2023, he was promoted to blue belt in Brazilian jiu-jitsu by Dave Camarillo.[196] Four months later, Zuckerberg announced that he was preparing to make his MMA debut but had suffered an anterior cruciate ligament injury in training that required surgery and had delayed this.[197]

See also

References

- ^ Burrell, Ian (July 24, 2010). "Mark Zuckerberg: He's got the whole world on his site". The Independent. Archived from the original on October 28, 2023.

- ^ Shaer, Matthew (May 4, 2012). "The Zuckerbergs of Dobbs Ferry". New York. No. May 14, 2012. Archived from the original on May 10, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Pfeffer, Anshel (October 4, 2017). "Mark Zuckerberg's carefully curated Jewish conscience is both shallow and evasive". Haaretz. Archived from the original on May 12, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Vargas, Jose Antonio (September 20, 2010). "The Face of Facebook". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on September 18, 2010. Retrieved September 22, 2010.

- ^ Zuckerberg, Mark (January 27, 2017). "My great grandparents came from Germany, Austria, and Poland". Facebook. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick, David (2010). The Facebook Effect: The Inside Story of the Company That Is Connecting the World. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-1-4391-0211-4. Archived from the original on November 12, 2012. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ Grynbaum, Michael M. (June 10, 2004). "Mark E. Zuckerberg '06: The whiz behind thefacebook.com". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on September 29, 2010. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ Wagner, Kurk (May 24, 2017). "Before Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg built a chat network called ZuckNet". Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ Hemos/Dan Moore (April 21, 2003). "Machine Learning and MP3s". Slashdot. Archived from the original on February 10, 2023. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

- ^ Dreier, Troy (February 8, 2005). "Synapse Media Player Review". PC Magazine. Archived from the original on September 16, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

- ^ Larson, Chase (March 25, 2011). "Mark Zuckerberg speaks at BYU, calls Facebook "as much psychology and sociology as it is technology"". Deseret News. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ Madrigal, Alexis. "Before It Conquered the World, Facebook Conquered Harvard". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on March 12, 2024. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ Carson, Biz. "This is the true story of how Mark Zuckerberg founded Facebook, and it wasn't to find girls". Business Insider. Archived from the original on May 1, 2024. Retrieved May 1, 2024.

- ^ a b Grimland, Guy (October 5, 2009). "Facebook founder's roommate recounts creation of Internet giant". Haaretz. Archived from the original on October 22, 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "Britannica Money". Encyclopædia Britannica. May 20, 2024. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg's career in 90 seconds". The Daily Telegraph. February 7, 2017. Archived from the original on March 3, 2017. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ Hoffman, Claire (June 28, 2008). "The Battle for Facebook". Rolling Stone. New York City. Archived from the original on July 3, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ Seward, Zachary M. (July 25, 2007). "Judge Expresses Skepticism About Facebook Lawsuit". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved April 30, 2008.

- ^ a b Antonas, Steffan (May 10, 2009). "Did Mark Zuckerberg's Inspiration for Facebook Come Before Harvard?". ReadWrite Social. SAY Media, Inc. Archived from the original on February 1, 2012. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ a b Carlson, Nicolas (March 5, 2010). "In 2004, Mark Zuckerberg Broke Into A Facebook User's Private Email Account". Business Insider. Archived from the original on May 8, 2019. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ Kaplan, Katherine A. (November 19, 2003). "Facemash Creator Survives Ad Board". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on May 4, 2019. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- ^ "In 2004, Mark Zuckerberg Broke into a Facebook User's Private Email Account". Business Insider. Archived from the original on May 8, 2019. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ "The Duplicitous Deeds of Mark Zuckerberg". The Atlantic. March 5, 2010. Archived from the original on October 31, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ Stone, Brad (June 28, 2008). "Judge Ends Facebook's Feud With ConnectU". The New York Times blog. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ^ Rushe, Dominic (February 2, 2012). "Facebook IPO sees Winklevoss twins heading for $300m fortune". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- ^ Carlson, Nicholas (March 5, 2010). "At Last – The Full Story Of How Facebook Was Founded". Business Insider. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ * Holt, Chris (March 10, 2004). "Thefacebook.com's darker side". The Stanford Daily. Archived from the original on June 14, 2010.

- Nguyen, Lananh (April 12, 2004). "Online network created by Harvard students flourishes". The Tufts Daily. College Media Network. Archived from the original on October 15, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- Rotberg, Emily (April 14, 2004). "Thefacebook.com opens to Duke students". The Chronicle. Duke Student Publishing Company. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- "Students flock to join college online facebook". The Daily Pennsylvanian. Archived from the original on August 25, 2011.

- ^ Klepper, David (November 9, 2011). "Mark Zuckerberg, Harvard dropout, returns to open arms". Christian Science Monitor. Boston, Massachusetts: Christian Science Publishing Society. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ Teller, Sam (November 1, 2005). "Zuckerberg To Leave Harvard Indefinitely". The Harvard Crimson. The Harvard Crimson, Inc. Archived from the original on March 27, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ Kevin J. Feeney (February 24, 2005). "Business, Casual". The Harvard Crimson. The Harvard Crimson, Inc. Archived from the original on March 5, 2019. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "Face-to-Face with Mark Zuckerberg '02". Phillips Exeter Academy. January 24, 2007. Archived from the original on February 2, 2012. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ Coker, Mark (March 26, 2007). "Startup advice for entrepreneurs from Y Combinator". Venture Beat. Archived from the original on June 25, 2017.

- ^ a b Singel, Ryan (May 28, 2010). "Epicenter: Mark Zuckerberg: I Donated to Open Source, Facebook Competitor". Wired. Archived from the original on September 1, 2010. Retrieved May 29, 2010.

- ^ MacMillan, Robert (April 1, 2009). "Yu, Zuckerberg and the Facebook fallout". Reuters. Archived from the original on April 3, 2009. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

In a back-to-the-future move, former Netscape CFO Peter Currie will be the key adviser to Facebook about financial matters, until a new search for a CFO is found, sources said.

- ^ Zuckerberg, Mark (July 22, 2010), 500 Million Stories, The Facebook Blog, archived from the original on May 20, 2012, retrieved May 21, 2012

- ^ a b c Levy, Steven (April 19, 2010). "Geek Power: Steven Levy Revisits Tech Titans, Hackers, Idealists". Wired. Archived from the original on September 22, 2010. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ^ a b McGirt, Ellen (February 17, 2010). "The World's Most Innovative Companies 2010". Fast Company. Archived from the original on July 20, 2010. Retrieved September 24, 2010.

- ^ "2007 Young Innovators Under 35: Mark Zuckerberg, 23". MIT Technology Review. 2007. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- ^ "The Vanity Fair 100". Vanity Fair. October 2010. Archived from the original on September 25, 2010. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ^ "The Vanity Fair 100". Vanity Fair. September 1, 2010. Archived from the original on August 28, 2010. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg – 50 People who matter 2010". New Statesman. UK. Archived from the original on September 30, 2010. Retrieved September 27, 2010.

- ^ "Facebook's Zuckerberg says Steve Jobs advised on company focus, management". Bloomberg News. November 7, 2011. Archived from the original on November 10, 2011. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ^ Kramer, Andrew E. (October 1, 2012). "Zuckerberg Meets With Medvedev in a Crucial Market". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- ^ Elder, Miriam (October 1, 2012). "Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg meets excited Russian prime minister". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on April 3, 2023. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- ^ "Russia pushes Facebook to open research center". Fox News. October 1, 2012. Archived from the original on December 9, 2014. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

- ^ "Russia pushes Facebook to open research center". CBS News. October 1, 2012. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- ^ Delo, Cotton (April 16, 2013). "Facebook Practices What It Preaches for 'Home' Ad Blitz". Ad Age. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ^ Caitlin Dewey (August 19, 2013). "Mark Zuckerberg's Facebook page was hacked by an unemployed web developer". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 19, 2013. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- ^ a b Edwards, Victoria (September 21, 2013). "6 Things We Learned From Marissa Mayer and Mark Zuckerberg at TechCrunch Disrupt 2013". TechCrunch. AOL Inc. Archived from the original on September 24, 2013. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ^ Stevenson, Alastair (August 22, 2013). "Mark Zuckerberg Creates Tech Justice League to Bring Internet to the Masses". Search Engine Watch. Incisive Media Incisive Interactive Marketing LLC. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ^ * Samuel Gibbs (February 23, 2014). "Mark Zuckerberg goes to Barcelona to make mobile friends". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 2, 2014. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- Sven Grundberg (January 16, 2014). "Facebook's Zuckerberg to Speak at Mobile World Congress". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on February 18, 2014. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- Meyer, David (January 16, 2014). "Facebook's Zuckerberg to headline Mobile World Congress this year". Gigaom. Gigaom, Inc. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ Mark Gregory (February 22, 2014). "Mobile World Congress: What to expect from Barcelona". BBC News. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ Alex Hern, Jonathan Kaiman (October 23, 2014). "Mark Zuckerberg addresses Chinese university in Mandarin". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 13, 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ^ Maria Tadeo (December 12, 2014). "Mark Zuckerberg Q&A: What we learnt about the Facebook founder". The Independent. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ^ Sam Colt (December 12, 2014). "Facebook May Be Adding a 'Dislike' Button". Inc. Monsueto Ventures. Archived from the original on March 20, 2015. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ^ "Facebook, Inc. Proxy Statement". United States Security and Exchange Commission. April 26, 2013. p. 31. Archived from the original on June 23, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

On January 1, 2013, Mr. Zuckerberg's annual base salary was reduced to $1 and he will no longer receive annual bonus compensation under our Bonus Plan.

- ^ "The top 10 business visionaries creating value for the world". Business Insider. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ "Zuckerberg finally gets Harvard degree". BBC News. May 25, 2017. Archived from the original on May 30, 2020. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- ^ Steinbock, Anna (May 25, 2017). "Harvard awards 10 honorary degrees". Harvard Gazette. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ Ojalvo, Holly Epstein. "Mark Zuckerberg finally got his Harvard degree". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 3, 2020. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- ^ "Facebook plans to let Messenger, Instagram, and WhatsApp users message each other". The Verge. January 25, 2019. Archived from the original on January 25, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ "Facebook begins merging Instagram and Messenger chats in new update". The Verge. August 14, 2020. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Martey Dodoo (August 16, 2004). "Wirehog?". Martey Dodoo. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ^ Alan J. Tabak (August 13, 2004). "Zuckerberg Programs New Website". Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on August 23, 2010. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ^ "80000 developers". Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ^ Jessi Hempel (May 17, 2018). "What Happened to Internet.org, Facebook's Grand Plan to Wire the World?". wired.com. Archived from the original on March 1, 2020. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- ^ "Meet at the Silicon Valley among the tech leaders and Indian Prime Minister-Narendra Modi". Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved October 9, 2015.

- ^ Lee, Seung (April 13, 2016). "Mark Zuckerberg just joined a new project to explore the universe faster". Newsweek. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ Logged in as click here to log out (February 12, 2009). "Facebook paid up to $65m to founder Mark Zuckerberg's ex-classmates". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on December 16, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ McCarthy, Caroline (November 30, 2007). "article about 02138". News.com. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- ^ Carlson, Nicholas (May 15, 2012). "EXCLUSIVE: How Mark Zuckerberg booted his co-founder out of the company". Business Insider. Archived from the original on September 1, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ Hempel, Jessi (July 25, 2009). "The book that Facebook doesn't want you to read". CNN. Archived from the original on September 14, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2011.

- ^ West, Jackson (June 18, 2010). "Facebook CEO Named in Pakistan Criminal Investigation". NBC Bay Area. Archived from the original on June 21, 2010. Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- ^ "Pakistani lawyer petitions for death of Mark Zuckerberg". The Register. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ Anderson, John (July 29, 2010). "Facebook does not have a like button for Ceglia". WellsvilleDaily.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ "Venture beat coverage of Ceglia lawsuit". July 20, 2010. Archived from the original on December 2, 2017. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- ^ "Feds Collar Would-Be Facebook Fraudster". E-Commerce News. October 29, 2012. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- ^ "A Dubious Case Found Lawyers Eager to Make Some Money". The New York Times. October 29, 2012. Archived from the original on December 2, 2017. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ "Paul Ceglia's lawyer drops out of Facebook suit after arrest". San Jose Mercury News. October 30, 2012. Archived from the original on March 2, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- ^ a b "Hawaiians call Mark Zuckerberg 'the face of neocolonialism' over land lawsuits". The Guardian. January 23, 2017. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ Mark Zuckerberg hits back at 'misleading' claims he is suing Hawaiian landowners Archived November 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Wired, January 20, 2017

- ^ "Facebook's Zuckerberg officially drops Hawaii 'quiet title' actions" Archived March 4, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Pacific Business News, February 26, 2017

- ^ Hendel, John (2018). "Zuckerberg testimony: 'We didn't do enough'". politico.eu.

"We didn't take a broad enough view of our responsibility, and that was a big mistake"

- ^ "Facebook, Social Media Privacy, and the Use and Abuse of Data". United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary. April 10, 2018. Archived from the original on September 8, 2019. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "MArk Zuckerberg Facebook Post". Facebook. April 28, 2018. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022.

- ^ "Zuckerberg's snub to MPS 'astonishing'". BBC News. March 27, 2018. Archived from the original on May 29, 2018. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ "Senate Commerce votes to issue subpoenas to CEOs of Facebook, Google and Twitter". CNN. October 2020. Archived from the original on October 11, 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ "Facebook, Twitter and Google CEOs grilled by Congress on misinformation". CNN. March 25, 2021. Archived from the original on March 25, 2021. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ Kelly, Heather; Lima-Strong, Cristiano; Zakrzewski, Cat (January 31, 2024). "Mark Zuckerberg apologizes to parents at Senate child safety hearing". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 14, 2024.

- ^ Hamilton, David (February 1, 2024). "Mark Zuckerberg's long apology tour: A brief history". Associated Press. Archived from the original on February 26, 2024.

- ^ Fung, Brian (November 8, 2023). "Mark Zuckerberg personally rejected Meta's proposals to improve teen mental health, court documents allege". CNN. Archived from the original on November 9, 2023. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ^ Fried, Ina (June 2, 2010). "Zuckerberg in the hot seat at D8". CNET. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- ^ Harlow, John (May 16, 2010). "Movie depicts seamy life of Facebook boss". The Times. Archived from the original on November 18, 2020. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- ^ Cieply, Michael & Helft, Miguel (August 20, 2010). "Facebook Feels Unfriendly Toward Film It Inspired". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 9, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2010.

- ^ Harris, Mark (September 17, 2010). "Inventing Facebook". New York. Archived from the original on September 22, 2010. Retrieved September 22, 2010.

- ^ "The Social Network Filmmakers Thank Zuckerberg During Golden Globes". Techland. January 17, 2011. Archived from the original on January 20, 2011. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- ^ "Last Night, Aaron Sorkin Demonstrated How to Apologize Without Accepting Responsibility". New York. January 17, 2011. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg Meets Jesse Eisenberg on Saturday Night Live". People. January 30, 2011. Archived from the original on January 31, 2011. Retrieved January 30, 2011.

- ^ "Jesse Eisenberg meets the real Mark Zuckerberg on SNL". Digital Trends. January 31, 2011. Archived from the original on February 10, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- ^ "Jesse Eisenberg Calls Mark Zuckerberg "Sweet" and "Generous" in His Funny Oscar Nominees Lunch Interview" Archived February 10, 2011, at the Wayback Machine PopSugar, February 7, 2011

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg Meets Jesse Eisenberg On The 'Saturday Night Live' Stage" Archived April 5, 2015, at the Wayback Machine NPR, January 30, 2011

- ^ "The Facebook Effect: The Inside Story of the Company That Is Connecting the World" Archived December 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, release date February 1, 2011

- ^ a b Rohrer, Finlo. "Is the Facebook movie the truth about Mark Zuckerberg" Archived November 23, 2018, at the Wayback Machine BBC, September 30, 2010

- ^ "Facebook Creator Mark Zuckerberg to Get Yellow on The Simpsons". New York. July 21, 2010. Archived from the original on July 25, 2010. Retrieved September 22, 2010.

- ^ Griggs, Brandon (October 11, 2010). "Facebook, Zuckerberg spoofed on 'SNL'". CNN. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved October 11, 2010.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg 'Liked' SNL's Facebook Skit". New York. October 12, 2010. Archived from the original on October 15, 2010. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- ^ Lerer, Lisa & McMillan, Traci (October 30, 2010). "Comedy Central's Stewart Says Press, Politicians Are Creating Extremism". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on November 3, 2010. Retrieved November 4, 2010.

- ^ Nina Metz (July 18, 2013). "Terms and Conditions May Apply". Chicago Closeup. Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 24, 2014. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ^ Catsoulis, Jeannette (July 11, 2013). "'Terms and Conditions May Apply' Details Digital-Age Loss of Privacy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 10, 2023. Retrieved May 25, 2014. (paid)

- ^ Hoback, Cullen (September 19, 2013). "Our data is our digital identity – and we need to reclaim control | Technology". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 21, 2014. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg savaged by 'South Park'". CNET. October 12, 2017. Archived from the original on March 29, 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ^ Ng, Philiana (September 24, 2010). "Mark Zuckerberg: 'The Social Network' is 'fun'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012.

- ^ Tracy, Ryan (November 23, 2010). "Can Mark Zuckerberg's Money Save Newark's Schools?". Newsweek. Archived from the original on November 30, 2010.

- ^ Reidel, David (September 22, 2010). "Facebook CEO to Gift $100M to Newark Schools". CBS News. Archived from the original on September 24, 2010. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg's Well-Timed $100 million Donation to Newark Public Schools". New York. September 22, 2010. Archived from the original on September 26, 2010. Retrieved September 28, 2010.

- ^ a b Isaac, Mike (September 24, 2010). "Zuckerberg Pressured To Announce $100 million Donation To Newark". Forbes. Archived from the original on September 26, 2010. Retrieved September 28, 2010.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg's $100 million donation to Newark public schools failed miserably — here's where it went wrong". Yahoo! Finance. September 25, 2015. Archived from the original on November 19, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ Kotlowitz, Alex (August 19, 2015). "'The Prize,' by Dale Russakoff". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 5, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ * Gonzales, Sandra (December 8, 2010). "Zuckerberg to donate wealth". San Jose Mercury News. Archived from the original on February 21, 2011. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- "US billionaires pledge 50% of their wealth to charity". BBC. August 4, 2010. Archived from the original on August 30, 2010. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- Moss, Rosabeth (December 14, 2010). "Four Strategic Generosity Lessons". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on February 25, 2011. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ^ The Giving Pledge Archived December 31, 2017, at the Wayback Machine website. Retrieved December 3, 2015

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan". The Giving Pledge. Archived from the original on August 28, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ^ * Bailey, Brandon (December 19, 2013). "Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg makes $1 billion donation". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on December 20, 2013. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Sparkes, Matthew (December 19, 2013). "Mark Zuckerberg donates $1bn to charity". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Wagner, Kurt (January 3, 2014). "Zuckerberg's Other Billion-Dollar Idea: 2013's Biggest Charitable Gift". Mashable. Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ^ "Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg biggest giver in 2013". USA Today. February 10, 2014. Archived from the original on December 2, 2017. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- ^ Phillip, Abby (October 14, 2014). "Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg and wife Priscilla Chan donate $25 million to Ebola fight". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 20, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ Kroll, Luisa (October 14, 2014). "Mark Zuckerberg Is Giving $25 Million To Fight Ebola". Forbes. Archived from the original on October 22, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ * Botelho, Greg (February 7, 2015). "Zuckerberg, wife give $75 million to San Francisco General Hospital". CNN Business. Archived from the original on February 3, 2024.

- Schleifer, Theodore (December 15, 2020). "Mark Zuckerberg gave $75 million to a San Francisco hospital. The city has condemned him anyway". Vox. Archived from the original on April 19, 2024.

- Har, Janie (December 15, 2020). "San Francisco board rebukes naming hospital for Facebook CEO". Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 16, 2024.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg Vows to Donate 99% of His Facebook Shares for Charity". The New York Times. December 1, 2015. Archived from the original on July 23, 2018. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ "Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg to give away 99% of shares". BBC News. December 1, 2015. Archived from the original on December 2, 2015. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg and the Rise of Philanthrocapitalism". The New Yorker. December 2, 2015. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg's Philanthropy Uses L.L.C. for More Control". The New York Times. December 2, 2015. Archived from the original on January 12, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ "The Merits and Drawbacks of Philanthrocapitalism". Berkeley Economic Review. March 14, 2019. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions – Chan Zuckerberg Biohub". Czbiohub.org. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ Maxmen, Amy (February 16, 2017). "'Riskiest ideas' win $50 million from Chan Zuckerberg Biohub". Nature. 542 (7641): 280–281. Bibcode:2017Natur.542..280M. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.21440. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 28202988.

- ^ "Document Shows How Mark Zuckerberg's New Science Charity Will Handle IP". BuzzFeed News. November 1, 2016. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ Kaiser, Jocelyn (February 8, 2017). "Chan Zuckerberg Biohub funds first crop of 47 investigators". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aal0719. Archived from the original on March 4, 2022. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ "FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS: CHAN ZUCKERBERG BIOHUB INTERCAMPUS RESEARCH AWARDS". Chan Zuckerberg Biohub Network. Archived from the original on December 5, 2020. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg And Priscilla Chan Donate $25M To Gates Foundation Coronavirus Accelerator". Benzinga. March 30, 2020. Archived from the original on April 2, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Allen, Mike (March 30, 2020). "Mark Zuckerberg: "Local journalism is incredibly important" to fighting coronavirus crisis". Axios. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ Katharine Mieszkowski (April 19, 2011). "President Obama's Facebook appearance aimed at young voters; Bay Area visit targets big donors". The Bay Citizen. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- ^ Cohen, David (February 14, 2013). "Protestors Target Mark Zuckerberg's Fundraiser For N.J. Gov. Chris Christie". AllFacebook. Archived from the original on August 4, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- ^ Julia Boorstin (February 13, 2013). "Mark Zuckerberg 'Likes' Governor Chris Christie". CNBC. Archived from the original on April 6, 2013. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ^ Kate Zernike (January 24, 2013). "Facebook Chief to Hold Fund-Raiser for Christie". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 22, 2013. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ^ Young, Elise (June 8, 2013). "Zuckerberg Plans Fundraiser for Cory Booker's Senate Run". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on October 23, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ^ Christine Richard, "Ackman Cash for Booker Brings $240 Million Aid From Wall Street" Archived October 30, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Bloomberg, October 28, 2010

- ^ "Education". Silicon valley Community Foundation. Archived from the original on June 3, 2013. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ^ Cassidy, Mike (February 15, 2013). "Cassidy: Silicon Valley needs to harness its innovative spirit to level the playing field for blacks and Hispanics". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ Constine, Josh (April 11, 2013). "Zuckerberg And A Team Of Tech All-Stars Launch Political Advocacy Group FWD.us". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- ^ Ferenstein, Gregory (April 11, 2013). "Zuckerberg Launches A Tech Lobby, But What Will It Do Differently?". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- ^ Zuckerberg, Mark (April 11, 2013). "Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg: Immigration and the knowledge economy". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 13, 2013. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- ^ "About Us". FWD.us. Archived from the original on April 13, 2013. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- ^ Handley, Meg (April 30, 2013). "Facebook's Zuckerberg Takes Heat Over Keystone, Drilling Ads". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on May 3, 2013. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ Weiner, Rachel. "Liberal groups boycotting Facebook over immigration push". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 22, 2013. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ Constine, Josh (June 20, 2013). "Zuckerberg Replies To His Facebook Commenters' Questions On Immigration". TechCrunch. Aol Tech. Archived from the original on June 24, 2013. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ^ Gallagher, Billy (June 30, 2013). "Mark Zuckerberg 'Likes' SF LGBT Pride As Tech Companies Publicly Celebrate Equal Rights". TechCrunch. AOL Inc. Archived from the original on July 5, 2013. Retrieved July 2, 2013.

- ^ Evelyn M. Rusli (June 30, 2013). "Mark Zuckerberg Leads 700 Facebook Employees in SF Gay Pride". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on July 2, 2013. Retrieved July 2, 2013.

- ^ Emery, Debbie (December 9, 2015). "Mark Zuckerberg Vows to 'Fight to Protect' Muslim Rights on Facebook". TheWrap. Archived from the original on December 11, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ White, Daniel (December 9, 2015). "Mark Zuckerberg Offers Support to Muslims in Facebook Post". Time. Archived from the original on December 9, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ Griffin, Andrew (December 9, 2015). "Mark Zuckerberg speaks in support of Muslims after week of 'hate'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 10, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ Cenk Uygur (December 10, 2015). "Mark Zuckerberg Stands With Muslims". The Young Turks. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ "Zuckerberg Invokes Jewish Heritage in Facebook Post Supporting Muslims". Haaretz. December 10, 2015. Archived from the original on December 10, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ Tait, Robert (December 9, 2015). "Mark Zuckerberg voices support for Muslims amid Donald Trump ban row". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ a b King, Shaun (February 25, 2016). "Mark Zuckerberg forced to address racism among Facebook staff after vandals target Black Lives Matter phrases". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on February 2, 2019. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ^ Jessica, Guynn (February 25, 2016). "Zuckerberg reprimands Facebook staff defacing 'Black Lives Matter' slogan". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 18, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ^ Snyder, Benjamin (February 25, 2016). "Mark Zuckerberg Takes Facebook Workers to Task Over 'All Lives Matter' Graffiti". Fortune. Archived from the original on February 25, 2016. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ^ Wong, Julia Carrie (January 28, 2017). "Mark Zuckerberg challenges Trump on immigration and 'extreme vetting' order". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ Bollag, Sophia (October 23, 2019). "Petitions for a property tax change are coming to a grocery store near you. Here's what to know". The Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original on March 4, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ Schleifer, Theodore; Isaac, Mike (September 27, 2024). "Mark Zuckerberg Is Done With Politics". New York Times. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg says White House 'pressured' Facebook to censor Covid-19 content". The Guardian. August 27, 2024. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ Shapero, Julia (August 26, 2024). "Zuckerberg says he regrets not being more outspoken about 'government pressure' on COVID content". The Hill. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ "Business Zuckerberg says the White House pressured Facebook over some COVID-19 content during the pandemic". Associated Press. August 27, 2024. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ O'Connor, Clare (May 20, 2012). "Mark Zuckerberg's Wife Priscilla Chan: A New Brand of Billionaire Bride". Forbes. Archived from the original on May 22, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ "White Coats on a Rainbow of Students" Archived January 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Spotlight, UCSF School of Medicine. Cf. Priscilla Chan, 23.

- ^ Spiegel, Rob (December 20, 2010). "Zuckerberg Goes Searching in China". Archived from the original on December 2, 2017. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- ^ "Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg learn chinese every morning". ChineseTime.cn. September 29, 2010. Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ "Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg marries Priscilla Chan". CBS News. Archived from the original on August 13, 2013. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ Wohlsen, Marcus (May 19, 2012). "Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg marries longtime girlfriend, Priscilla Chan: Palo Alto, Calif., ceremony caps busy week after company goes public". NBC News. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ "Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg to become a father". BBC News. July 31, 2015. Archived from the original on December 2, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2015.

- ^ Frankel, Todd C.; Fung, Brian; Layton, Lyndsey. "Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan to give away 99 percent of their Facebook stock, worth $45 billion". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ Kell, John (February 8, 2016). "Mark Zuckerberg Reveals Daughter's Chinese Name". Fortune. Archived from the original on March 6, 2021. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

In a pretty adorable video shared by the tech executive over the weekend, Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan said their daughter Max's Chinese name is Chen Mingyu.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg and his wife just unveiled their new baby girl to the world". Fox News. August 28, 2017. Archived from the original on August 28, 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ Slater, Georgia (March 24, 2023). "Mark Zuckerberg and Wife Priscilla Chan Welcome Baby No. 3, Daughter Aurelia: 'Little Blessing'". People. Archived from the original on March 24, 2023. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- ^ "Meet Beast Zuckerberg, your new favorite dog rug". CBS News. December 7, 2015. Archived from the original on May 9, 2019. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ King, Hope (September 22, 2016). "Mark Zuckerberg's dog Beast is 'moping' over new baby". CNN. Archived from the original on May 9, 2019. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ Faguy, Ana (August 14, 2024). "Mark Zuckerberg reveals 'Roman' statue of wife". BBC News. Archived from the original on September 11, 2024.

- ^ Grossman, Lev (December 15, 2010). "Person of the Year 2010: Mark Zuckerberg". Time. Archived from the original on August 17, 2013.

- ^ "The 100 most influential people in AI 2024". TIME. Archived from the original on September 18, 2024. Retrieved September 18, 2024.

- ^ "The World's Most Powerful People". Forbes. December 2016. Archived from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg". Forbes. October 2023. Archived from the original on October 26, 2023. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg". Forbes. Archived from the original on December 22, 2022. Retrieved January 6, 2024.

- ^ Vara, Vauhini (November 28, 2007). "Just How Much Do We Want to Share On Social Networks?". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 13, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ^ Zauzmer, Julie (December 30, 2016). "Mark Zuckerberg says he's no longer an atheist, believes 'religion is very important'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 31, 2019. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ Isaac, Mike (May 25, 2017). "Mark Zuckerberg's great American road trip". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ "Facebook's Zuckerberg visits Mother Emanuel AME Church". CNN. March 13, 2017. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 18, 2022.