The 1964 24 Hours of Le Mans was the 32nd Grand Prix of Endurance, and took place on 20 and 21 June 1964. It was also the ninth round of the 1964 World Sportscar Championship season.

| |||

This year marked the arrival of American teams in force, with Ford V8 engines in ten cars. It also marked the last appearance of Aston Martin and Jaguar for twenty years.[1] Over half the entrants were mid- or rear-engined, and almost half the field had a 3-litre engine or bigger. But the number of retirements due to gearbox and clutch issues from the increased power in the cars was noticeable.[2]

Ferrari was the winner for a record fifth year in a row – the 275 P of Nino Vaccarella and former Ferrari-privateer Jean Guichet covered a record distance. The second was the Ferrari of Graham Hill and Jo Bonnier for the British Maranello Concessionaires team, ahead of the works 330 P of John Surtees and Lorenzo Bandini. Ferrari dominance of the GT category was broken for the first time however by the new Shelby Cobra of Dan Gurney and Bob Bondurant finishing in fourth ahead of two of the Ferrari 250 GTOs.

Regulations

editAside from a few adjustments to the sliding scale of minimum weight to engine capacity, the Automobile Club de l'Ouest (ACO) made very few changes to its regulations this year. With the greatly disparate speeds, the minimum engine size was increased from 700cc to 1000cc.[1] Otherwise, the final lap now had to be completed in fifteen minutes, down from twenty minutes.[3][4]

Entries

editThe ACO received 71 entries and 55 cars arrived to practice, with 10 reserves. There was a strong turn-out from the current Formula 1 drivers, with the notable exception of Jim Clark and Jack Brabham.[5] The proposed entry list comprised:

| Category | Classes | Prototype Entries |

GT Entries |

Total Entries |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large-engines | 5.0+, 5.0, 4.0, 3.0L | 12 (+1 reserve) | 14 (+2 reserves) | 26 |

| Medium-engines | 2.5, 2.0, 1.6L | 3 | 11 (+2 reserves) | 14 |

| Small-engines | 1.3, 1.15, 1.0L | 13 (+5 reserves) | 2 | 15 |

| Total Cars | 28 (+6 reserves) | 27 (+4 reserves) | 55 |

Defending champions Ferrari again arrived in force, with twelve entrants. To meet the Ford challenge, the factory team brought two new models. The 275 P was the next development of the previous year's race-winning 250 P and the new 3.3-litre V12 developed 320 bhp. Ludovico Scarfiotti, winner of that 1963 race was paired with Mike Parkes, Umberto Maglioli with Giancarlo Baghetti. Stalwart Ferrari privateer Jean Guichet was rewarded with a works drive this year alongside Nino Vaccarella. The team's F1 drivers, John Surtees and Lorenzo Bandini, drove the 330 P, a new model for this race. The 4.0-litre V12 developed 370 bhp capable of 305 kp/h (190 mph). Ferrari also supplied two 330 P's to their American and British customer teams, the North American Racing Team (NART) for Pedro Rodriguez and Skip Hudson, and Maranello Concessionaires for Graham Hill and Jo Bonnier.[6] There was also a pair of 250 LM models run by the Equipe Nationale Belge and NART.

After a messy and unsuccessful attempt to purchase the Ferrari company (for US$16 million[7][8]), Ford pledged to build their own sports car to beat the Ferraris. In 1963, Ford had almost won the Indianapolis 500 at its first attempt, with Lotus. Eric Broadley’s Lola had performed well in the 1963 race and was taken on board to work on the new GT design.[9] The resulting GT40 (named for only being 40” high) bore a strong resemblance to the Lola Mk6. The Indianapolis powerplant, a 4.2L aluminium block Fairlane V8 engine developed 350 bhp capable of 340 kp/h (210 mph).[10] The issue had been finding a gearbox robust enough to handle the raw engine power, and the Colotti 5-speed box was chosen. John Wyer, from Aston Martin, was brought on as project manager and three cars were entered for the race. Americans Richie Ginther and Masten Gregory had one car, while Phil Hill was paired up with Kiwi Bruce McLaren and Jo Schlesser drove with Richard Attwood (who had driven the Lola in the 1963 race).

Col. John Simone's Maserati France continued to fly the flag for the manufacturer. In turn, Maserati revised their Tipo 151 giving it fuel-injection and over 400 bhp now making it able to reach 310 kp/h (190 mph).[11] Regular team driver André Simon, still recovering after a testing accident at Monza, was joined by fellow French veteran Maurice Trintignant.

New entrant Iso brought its new Grifo A3C, designed by Ferrari engineer Giotto Bizzarrini (who had previously designed the 250 GTO). Mounting a small-block, 327 cu in (5.35L), Chevrolet V8, it put out almost 400 bhp.[12]

Porsche moved on from derivatives of the 356 and introduced a new racer, the 904, to counter the new threats from Abarth and Alfa Romeo. However the proposed 200 bhp Flat-6 engine was not ready yet, so the GT cars were fitted with the Flat-4 from the 356 Carrera. Two prototypes were entered using the Flat-8 engine from the concluded Formula 1 program. Putting out 225 bhp made them the fastest ever 2-litre cars at Le Mans, capable of 280 kp/h (175 mph).[13] Regular team drivers Edgar Barth / Herbert Linge were joined by Gerhard Mitter / Colin Davis – who had earlier had a sensational win in the 1964 Targa Florio. The Porsche 2-litres were now being considered “dark horses” for an outright podium place.[5]

If the medium-sized engines were sparse, the small-engine prototype field bulged with variety. Five works teams were contesting the P-1150 class. Charles Deutsch returned with Panhard, after a year away, with the remarkable LM64 CD-3. Made of fibreglass, it had one of the most aerodynamic profiles of any car ever at Le Mans. Deutsch had to supercharge the 864cc Panhard engine (putting out 70 bhp) to meet the new 1000cc minimum engine size, using the x1.4 equivalence formula but that could push the car up to 220 kp/h (137 mph).[14][4]

René Bonnet, the previous year's class winner, returned with five cars including a pair of the victorious Aérodjet LM6s, now with an 1149cc Renault engine.[15] Alpine returned after a tragic debut the previous year. They ran five cars – a mix of the updated M64 and the older M63 variants and running either 1149cc or 1001cc Renault engines.[16]

The Ferrari 250 GTO had delivered Ferrari the GT victory for two years running. Four customer teams (NART, Maranello Concessionaires, Equipe Nationale Belge and privateer Fernand Tavano) entered the reliable 3-litre thoroughbred, now with new body-styling.[17]

As well as the Ford GT, Ford engines were also supplied to AC and Sunbeam with varying success. The Shelby Cobras had been very successful in American racing, and for the new year, it was given new aerodynamic bodywork and the bigger 289 cu in (4.7L) Windsor engine. Putting out nearly 400 bhp it was capable of 295 kp/h (180 mph) making it 10 kp/h faster than its Ferrari GTO competition.[10] Four cars were entered: two for Shelby American, and one each for Briggs Cunningham and Ed Hugus. In the end though only two arrived alongside a works-entry Cobra Coupé from AC Cars.

The Sunbeam Tiger was to be the Rootes Group answer to the AC Cobra. It used the 260cu in (4.3L) Windsor engine from Shelby American. The body was developed from the Alpine with Lister Cars, but being made of steel it was far too heavy. The 275 bhp could only get the car up to 230 kp/h (145 mph).[18]

Aston Martin shut down their racing department when John Wyer left to manage the Ford program, selling off the three DP prototypes. Mike Salmon bought one of the DP214s and entered it as a privateer.[19] Similarly, the Jaguar E-Type Lightweights were becoming obsolete and only two privateer entries arrived, from Peter Sargent and German Peter Lindner.[20]

The new Porsche 904 had quickly been homologated to the GT-category with the requisite production of 100 cars, most pre-sold for customer orders. Even with only the old Flat-4 engine, it could still reach 260 kp/h (160 mph).[13] Seven cars were entered for the race: aside from the works car there were entries from the new Racing Team Holland of Erik Hazelhoff Roelfzema and the Scuderia Filipinetti. Jean Kerguen and Jacques Dewes also gave up their Aston Martin (badly damaged at the previous year's race) for Dewes’ new 904.

Their only competition in-class was a works MGB entry, driven by British rally ace Paddy Hopkirk and Andrew Hedges. In the GT-1600 class the new Autodelta motorsport division of Alfa Romeo set its first development project to be the Giulia TZ. Now homologated to the GT-category, the uprated 1570cc engine developed 135 bhp with a top speed of 245 kp/h (150 mph). Three cars were entered by the Milanese Scuderia Sant Ambroeus team who had already taken class victories at the Sebring, Targa Florio and Nürburgring races.[18]

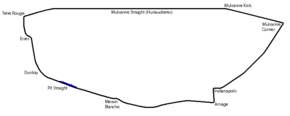

Practice

editThere was strong support at the Test Weekend on 18–19 April with 34 cars present, although the rain limited performance.[3] Ludovico Scarfiotti put up the fastest time, of 3m43.8 in the new Ferrari 275 P, with John Surtees not far behind with 3m45.9 in his 330 P stablemate.[21] A pair of Ford GTs made their first appearance but the results were disappointing. The car was unstable on the straight, with the nose lifting at speed. On the first day, Jo Schlesser had a major accident at the Mulsanne kink after hitting standing water.[22][4][23] The door flew off Roy Salvadori’s car, and the next day he also had an accident approaching the Mulsanne corner. Although uninjured, it was enough to convince Salvadori to leave the program.[10]

The Rover-BRM turbine car was at the April test weekend. But the car suffered damage on the trip back to the factory. This, as well as problems with the new heat-exchanger, meant it was not ready for the race itself.[24][4][1]

By race week, the Fords had got aerodynamic improvements making them much more competitive, including a tail ‘lip’ to reduce rear-end lift. At scrutineering though their fuel-tanks were found to be bigger than the 140-litre limit and displacement blocks had to be added.[25]

It was John Surtees who took pole position with a new record lap of 3m42.0 in his 330 P at dusk on the last practice.[25] He also slightly damaged the car when he hit a fox coming up to Maison Blanche.[6] Richie Ginther got his Ford into second with a 3m45.3, ahead of Pedro Rodriguez's NART Ferrari (3m.45.5) and Phil Hill's Ford (3m45.9). In fact the two manufacturers took the top nine grid positions. Dan Gurney was 10th in his Shelby Cobra (3m56.1) as the fastest GT car. The lead Shelby Cobra, along with the works AC and Aston Martin, were the only GTs to get under 4-minute laps.[25]

The Davis/Mitter Porsche was the fastest 2-litre, qualifying 18th (4m02.1) and the Delageneste/Morrogh Alpine was the fastest of the smaller cars with a 4m34.3 (35th).[26] But rally-specialist Pierre Orsini rolled his Alpine at Dunlop curve and broke his ankle.[16]

Race

editStart

editThe weather was cold but dry for the 4pm start. Just before the start ten spectators were seriously injured when an advertising hoarding they were on collapsed.

Pedro Rodríguez got the best start with the NART 330 P, with a power-slide and much tyre-noise.[27] His teammate, David Piper's Ferrari, burst an oil-line immediately and left a trail of oil through the Esses to where the car stopped at Tertre Rouge. Phil Hill had trouble starting his GT40, and was last away almost 70 seconds behind.[27] Giancarlo Baghetti bought in his SEFAC Ferrari with a chronic clutch problem, losing 75 minutes and 20 laps straight up.[28][6] Maurice Trintignant also bought in the Maserati with a lack of power – a sponge was found in an air intake.[11]

On the second lap with the cars wary of the oil flags, Ginther got a run on the three Ferraris ahead of him and blasted past them on the Mulsanne Straight doing 7200rpm (unofficially nearly 340kp/h).[23] Dropping back the revs to the 6500rpm prescribed by the team, he still managed to pull out a 40-second lead in the first hour covering a record 15 laps.[2][3] He led the Ferraris of Surtees, Rodriguez, Hill and Guichet. Then came the Cobras of Gurney and Sears, ahead of Attwood's Ford, Barth's Porsche and Tavano's Ferrari GTO rounding out the Top-10. But a bad first pit-stop dropped them to second behind the Surtees Ferrari. Phil Hill had made a half-dozen pit-stops with the troublesome Ford until the cause was traced to a blocked carburettor left uncleaned after an engine change the night before.[29]

Just on 6pm, Mike Rothschild lost control of his Triumph when overtaken by a Cobra in the Dunlop Curve. Sliding off the road, he just missed Hudson's NART Ferrari as he rebounded back into the middle of the road.[28] Although knocked unconscious Rothschild only suffered mild concussion.[30]

By dusk the Maserati had made up its two laps lost at the start and was running in third behind the SEFAC Ferraris. It was then delayed ten laps with ignition problems and retired before midnight with a complete electrical failure.[11] Edgar Barth became the first driver to do a sub-four minute lap in a 2-litre car with his Porsche prototype, an average speed just over 200 kp/h.[13][28] In the fifth hour, the Rodriguez/Hudson NART 330 P had to retire from 5th when it blew a head gasket.[6] The unreliability expected of a new car told as the Ginther/Gregory Ford was put out after 9.30pm with the gearbox only giving first or second gear. Dick Attwood had already retired from 6th when he had to bail out of his Ford when its engine caught fire on the Mulsanne Straight.[3][22][31]

Night

editUnusually for mid-summer, it was a bitterly cold night, with occasional patches of mist.[31] Around 10.15pm Peter Bolton's AC Cobra had a tyre blowout (transmission failure[32]) at Maison Blanche. The car spun and was then collected by the Ferrari of Giancarlo Baghetti. Tragically, the Ferrari (the Cobra[33]) speared off into the barriers and crushed three young French spectators. James Gilbert, Lionel Yvonnick (both 19) and Jacques Ledoux (17) had been standing in a prohibited area when struck by the Ferrari. Baghetti was uninjured, and Bolton was taken to hospital with minor injuries.[3][34]

At midnight the Ferraris were still running 1-2-3, with the Surtees/Bandini 330 P having done 119 laps, a lap ahead of the Vaccarella/Guichet 275 P and 3 laps ahead of the British 330 P of Hill/Bonnier. After alternator problems struck the Cunningham Cobra, their compatriots Gurney and Bondurant inherited their fourth place and heading the GT classes, five laps behind. Fifth, and a further lap back, was the 2-litre Porsche of Barth and Linge benefitting from the bigger cars’ issues, and leading the Index of Performance. The Hill/McLaren Ford had pushed its way back up to 6th[31] In their hard driving Phil Hill set a new lap record of 3m49.2. Soon after midnight the grandstand spectators were stunned when the transmission of José Rosinski's Ferrari GTO just exploded as it roared past the pits. Although bits of the differential peppered Lindner's Jaguar in the pits (getting a driveshaft change[20]) and flew off into the crowd, no-one was seriously injured.[17][31]

Then Surtees and Bandini, who had held the lead since the second hour, started having fuel leak problems. Going into the twelfth hour, they were overtaken by the 275 P of teammates Vaccarella and Guichet, alternating the race-lead on the pit-stop cycles.[31] At one point, Briggs Cunningham queried why more than the allowed number of mechanics were working on the car. Earlier Cunningham's Cobra had pitted to fix an alternator. A Ferrari mechanic saw them recharge the battery with a unit in the pits, informed the officials and the car was disqualified. This new accusation ignited an almighty row with team manager Dragoni chasing Cunningham out of the pits. The officials took no action against Bandini's Ferrari.[35][36]

At 2.30am the clutch of the leading Porsche broke, stranding Herbert Linge out at Tertre Rouge. Their teammates, Davis/Mitter up in 6th were also suffering clutch problems.[13]

Just before 4.30am there was a major accident on the front straight: Jean-Louis Marnat was seen slumped at the wheel of his Triumph. He had fallen unconscious from carbon monoxide poisoning after an earlier collision had damaged the exhaust.[30][31] The car hit the barrier, veered across the track into the pits just missing the Alpine and Bonnet teams and then rolled on until hitting the barriers at the Dunlop curve. It just missed Phil Hill's Ford GT which itself retired around 5.30am with gearbox problems after having got back up to fourth and setting a new lap record.[3][36]

Morning

editAround dawn the big Iso Grifo, which had got up to 9th by halftime pulled in for a long stop to fix seized brakes. They got going again in 21st, and eventually finished 14th.[12] The Lindner Jaguar was back in the pits just before 7am, overheating, but with 10 laps until its next permitted refill it was retired.[20][37]

At 7am Surtees lost second place as they took 10 minutes to address their fuel issues. Hill and Bonnier, moving up, were also having niggling problems with the throttle and clutch. Twice they were lucky that problems happened within coasting distance of the pits.[6][37] After stopping to adjust the gearbox early in the morning the Davis/Mitter Porsche had fallen from 8th back through the field. The clutch finally packed up after 11am.[13]

By 8am, after 16 hours, Ferraris were in the top four places. Vaccarella/Guichet had done 235 laps, now with a 7-lap lead over Hill/Bonnier and Surtees/Bandini. The Tavano Ferrari was leading the GTs in 4th on 222 laps, with the pursuing Cobra of Gurney/Bondurant and Ferrari GTO of “Beurlys”/Bianchi each a lap further back.[37]

Finish and post-race

editOnce again, with the pressure off the Ferraris could ease back. The Ferrari of Vaccarella and Guichet never missed a beat, gradually extending its lead, in the end winning comfortably by five laps setting a new distance record. It was a good reward for Jean Guichet who had previously finished third (1961) and second (1962) as a GT privateer. Ferrari swept the podium with the British 330 P of Graham Hill and Jo Bonnier second, seven laps ahead of Surtees and Bandini in the works car.

The Ferrari dominance in the GT-category was broken however. Despite having high engine temperatures through the second day, Dan Gurney and Bob Bondurant had a consistent run to bring home the Shelby American Daytona Coupé in fourth, first in the GT category, and a lap ahead of the nearest Ferrari GTOs. Those were the Equipe National Belge car of Bianchi/”Beurlys” and the Maranello car of Ireland/Maggs.

Porsche had a positive weekend. As well as Barth's lap-record for a 2-litre car, five of the six 904 GTs finished – in 7th, 8th, 10th, 11th and 12th led by French privateers Robert Buchet and Guy Ligier. Two of the Alfa Romeos finished, the leading one of Bussinello / Deserti just behind the Porsches and finally beating the class-distance record set by Porsche back in 1958.[38]

In a race of records, there were five new distance records set in the competing classes, including all three Prototype winners.[21] As in the previous year, the winning Ferrari also won the Index of Performance. Alpine got a 1–2 victory in the Index of Thermal Efficiency, the winners being Delageneste/Morrogh who finished 17th overall.

1964 proved to be a watershed for a number of manufacturers. Despite his racing success, it was the last time that René Bonnet bought his own cars to Le Mans. In financial trouble he sold his company to the new Matra car company a few months later.[15] Formerly closely tied to Bonnet, It was also the last appearance at Le Mans for Panhard, whose racing pedigree went back to 1895. Although very aerodynamically advanced, the CD-3 never raced again.[14]

Aston Martin had first raced in 1928, then had been at every race since 1931, including a victory in 1959. Although it briefly returned in 1977 and 1989, it would be 40 years until its reprise in 2005.[19] Likewise Jaguar, so dominant in the 1950s with five victories would not be seen again for 20 years, culminating with two further victories in 1988 and 1990. It was also the last appearance for the Cunningham team. Briggs Cunningham had been the main American presence postwar, bringing his own roadsters to push for outright victory in the 1950s. Now as the American teams started arriving in force, after 11 races the Cunningham team passed the baton on.

Peter Lindner, who had brought his privateer Jaguar to the race, would be killed at the end of the year in that car when he crashed in heavy rain at Montlhéry.[39] Dutchman Jonkheer Carel Godin de Beaufort, stalwart privateer Porsche driver in sports cars and F1 would also be killed later in the year, in practice for the German F1 Grand Prix.[40]

Official results

editFinishers

editResults taken from Quentin Spurring's book, officially licensed by the ACO[41] Class Winners are in Bold text.

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Laps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P 4.0 |

20 | SpA Ferrari SEFAC | Nino Vaccarella Jean Guichet |

Ferrari 275 P | Ferrari 3.3L V12 | 349 |

| 2 | P 4.0 |

14 | Maranello Concessionaires | Graham Hill Jo Bonnier |

Ferrari 330 P | Ferrari 4.0L V12 | 344 |

| 3 | P 4.0 |

19 | SpA Ferrari SEFAC | John Surtees Lorenzo Bandini |

Ferrari 330 P | Ferrari 4.0L V12 | 337 |

| 4 | GT 5.0 |

5 | Shelby-American Inc. | Dan Gurney Bob Bondurant |

Shelby Daytona Cobra Coupe | Ford 4.7L V8 | 334 |

| 5 | GT 3.0 |

24 | Equipe Nationale Belge | Lucien Bianchi “Beurlys” (Jean Blaton) |

Ferrari 250 GTO | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 333 |

| 6 | GT 3.0 |

25 | Maranello Concessionaires | Innes Ireland Tony Maggs |

Ferrari 250 GTO | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 328 |

| 7 | GT 2.0 |

34 | Auguste Veuillet | Robert Buchet Guy Ligier |

Porsche 904/4 GTS | Porsche 1967cc F4 | 323 |

| 8 | GT 2.0 |

33 | Racing Team Holland | Ben Pon Henk van Zalinge |

Porsche 904/4 GTS | Porsche 1967cc F4 | 319 |

| 9 | GT 3.0 |

27 | F. Tavano (private entrant) |

Fernand Tavano Bob Grossman |

Ferrari 250 GTO | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 315 |

| 10 | GT 2.0 |

31 | Porsche System Engineering | Gerhard 'Gerd' Koch Heinz Schiller |

Porsche 904/4 GTS | Porsche 1967cc F4 | 315 |

| 11 | GT 2.0 |

35 | Scuderia Filipinetti | Herbert Müller Claude Sage |

Porsche 904/4 GTS | Porsche 1967cc F4 | 309 |

| 12 | GT 2.0 |

32 | "Franc" (private entrant) |

“Franc” (Jacques Dewes) Jean Kerguen |

Porsche 904/4 GTS | Porsche 1967cc F4 | 308 |

| 13 | GT 1.6 |

57 | Scuderia St. Ambroeus | Roberto Bussinello Bruno Deserti |

Alfa Romeo Giulia TZ | Alfa Romeo 1570cc S4 | 307 |

| 14 | P +5.0 |

1 | Auguste Veuillet | Pierre Noblet Edgar Berney |

Iso Grifo A3C | Chevrolet 5.4L V8 | 307 |

| 15 | GT 1.6 |

41 | Scuderia St. Ambroeus | Giampiero Biscaldi Giancarlo Sala |

Alfa Romeo Giulia TZ | Alfa Romeo 1570cc S4 | 305 |

| 16 | P 4.0 |

23 | Equipe Nationale Belge | Pierre Dumay Gerard Langlois van Ophem |

Ferrari 250 LM | Ferrari 3.3L V12 | 298 |

| 17 | P 1.15 |

46 | Société des Automobiles Alpine | Roger Delageneste Henry Morrogh |

Alpine M64 | Renault-Gordini 1149cc S4 |

292 |

| 18 | GT 5.0 |

64 (reserve) |

Société Chardonnet | Régis Fraissinet Jean de Mortemart |

AC Cobra | Ford 4.7L V8 | 289 |

| 19 | GT 2.0 |

37 | British Motor Corporation | Paddy Hopkirk Andrew Hedges |

MG MGB Hardtop | MG 1801cc S4 | 287 |

| 20 | P 1.15 |

59 (reserve) |

Société des Automobiles Alpine | Roger Masson Teodoro Zeccoli |

Alpine M63B | Renault-Gordini 1001cc S4 |

284 |

| 21 | P 1.15 |

50 | Standard Triumph International |

David Hobbs Rob Slotemaker |

Triumph Spitfire | Triumph 1147cc S4 | 272 |

| 22 | GT 1.3 |

43 | Team Elite | Clive Hunt John Wagstaff |

Lotus Elite Mk14 | Coventry Climax 1216cc S4 |

266 |

| 23 | GT 1.15 |

52 | Société Automobiles René Bonnet |

Philippe Farjon Serge Lelong |

Bonnet Aérodjet LM6 | Renault-Gordini 1108cc S4 |

260 |

| 24 | P 1.15 |

53 | Donald Healey Motor Company | Clive Baker Bill Bradley |

Austin-Healey Sebring Sprite | BMC 1101cc S4 | 257 |

| N/C* | P 1.15 |

47 | Société des Automobiles Alpine | Mauro Bianchi Jean Vinatier |

Alpine M64 | Renault-Gordini 1001cc S4 |

230 |

- 'Note *: Not Classified because Insufficient distance covered.

Did Not Finish

edit| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Laps | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNF | P 2.0 |

30 | Porsche System Engineering | Colin Davis Gerhard Mitter |

Porsche 904/8 | Porsche 1981cc F8 | 244 | Clutch (20hr) |

| DSQ | GT 5.0 |

18 | M. Salmon (private entrant) |

Mike Salmon Peter Sutcliffe |

Aston Martin DP214 | Aston Martin 3.8L S6 | 235 | Premature oil change (19hr) |

| DNF | P 1.15 |

48 | Société Automobiles René Bonnet |

Robert Bouharde Michel de Bourbon-Parma |

Bonnet Aérodjet LM6 | Renault-Gordini 1149cc S4 |

216 | Gearbox (18hr) |

| DNF | P 5.0 |

10 | Ford Motor Company | Phil Hill Bruce McLaren |

Ford GT40 Mk.I | Ford 4.2L V8 | 192 | Gearbox (14hr) |

| DNF | GT 5.0 |

16 | P. Lindner (private entrant) |

Peter Lindner Peter Nöcker |

Jaguar E-Type Lightweight | Jaguar 3.8L S6 | 149 | Head gasket (16hr) |

| DNF | P 1.15 |

65 (reserve) |

Standard Triumph International |

Jean-François Piot Jean-Louis Marnat |

Triumph Spitfire | Triumph 1147cc S4 | 140 | Accident (14hr) |

| DNF | P 2.0 |

29 | Porsche System Engineering | Edgar Barth Herbert Linge |

Porsche 904/8 | Porsche 1981cc F8 | 139 | Clutch (11hr) |

| DNF | P 1.15 |

54 | Société des Automobiles Alpine |

Philippe Vidal Henri Grandsire |

Alpine A110 M64 | Renault-Gordini 1149cc S4 |

133 | Gearbox (15hr) |

| DSQ | GT +3.0 |

6 | Briggs S. Cunningham | Chris Amon Jochen Neerpasch |

Shelby Daytona Cobra Coupe | Ford 4.7L V8 | 131 | Outside assistance (11hr) |

| DNF | P 1.15 |

45 | Automobiles Charles Deutsch |

Pierre Lelong Guy Verrier |

CD 3 | Panhard 848cc supercharged F2 |

124 | Gearbox (13hr) |

| DNF | GT 5.0 |

9 | Rootes Group | Peter Procter Jimmy Blumer |

Sunbeam Tiger | Ford 4.3L V8 | 118 | Engine (10hr) |

| DNF | GT 3.0 |

26 | North American Racing Team | Ed Hugus José Rosinski |

Ferrari 250 GTO | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 110 | Propshaft (9hr) |

| DNF | P 5.0 |

2 | Maserati France | André Simon Maurice Trintignant |

Maserati Tipo 151/3 | Maserati 4.9L V8 | 99 | Electrical (9hr) |

| DNF | GT 5.0 |

17 | P.J. Sargent (private entrant) |

Peter Sargent Peter Lumsden |

Jaguar E-Type Lightweight | Jaguar 3.8L S6 | 80 | Gearbox (8hr) |

| DNF | P 1.15 |

44 | Automobiles Charles Deutsch |

Alain Bertaut André Guilhaudin |

CD 3 | Panhard 848cc supercharged F2 |

77 | Engine (10hr) |

| DNF | GT 5.0 |

3 | AC Cars Ltd. | Jack Sears Peter Bolton |

AC Cobra Coupé | Ford 4.7L V8 | 77 | Accident (7hr) |

| DNF | P 4.0 |

21 | SpA Ferrari SEFAC | Mike Parkes Ludovico Scarfiotti |

Ferrari 275 P | Ferrari 3.3L V12 | 71 | Oil pump (12hr) |

| DNF | P 4.0 |

22 | SpA Ferrari SEFAC | Giancarlo Baghetti Umberto Maglioli |

Ferrari 275 P | Ferrari 3.3L V12 | 68 | Accident (7hr) |

| DNF | P 5.0 |

11 | Ford Motor Company | Richie Ginther Masten Gregory |

Ford GT40 Mk.I | Ford 4.2L V8 | 63 | Gearbox (6hr) |

| DNF | P 1.15 |

56 | Société Automobiles René Bonnet |

Pierre Monneret Jean-Claude Rudaz |

Bonnet Aérodjet LM6 | Renault-Gordini 1001cc S4 |

62 | Engine (7hr) |

| DNF | P 4.0 |

15 | North American Racing Team | Pedro Rodríguez Skip Hudson |

Ferrari 330 P | Ferrari 4.0L V12 | 58 | Head gasket (5hr) |

| DNF | P 5.0 |

12 | Ford Motor Company | Richard Attwood Jo Schlesser |

Ford GT40 Mk.I | Ford 4.2L V8 | 58 | Fire (5hr) |

| DNF | P 1.15 |

55 | Société Automobiles René Bonnet |

Jean-Pierre Beltoise Gérard Laureau |

Bonnet RB5 | Renault-Gordini 1149cc S4 |

54 | Fuel pump (7hr) |

| DNF | GT 1.6 |

40 | Scuderia St. Ambroeus | Fernand Masoreo Jean Rolland |

Alfa Romeo Giulia TZ | Alfa Romeo 1570cc S4 | 47 | Accident (5hr) |

| DNF | P 1.15 |

60 (reserve) |

Société Automobiles René Bonnet |

Bruno Basini Roland Charrière |

Bonnet Aérodjet LM6 | Renault-Gordini 1149cc S4 |

44 | Engine (6hr) |

| DNF | GT 5.0 |

8 | Rootes Group | Claude Dubois Keith Ballisat |

Sunbeam Tiger | Ford 4.3L V8 | 37 | Engine (4hr) |

| DNF | P 1.15 |

49 | Standard Triumph International |

Michael Rothschild Bob Tullius |

Triumph Spitfire | Triumph 1147cc S4 | 23 | Accident (3hr) |

| DNF | P 1.3 |

42 | Lawrence Tune Engineering | Chris Lawrence Gordon Spice |

Deep Sanderson 301 | BMC 1293cc S4 | 13 | Overheating (3hr) |

| DNF | GT 1.6 |

38 | Royal Elysées (private entrant) |

René Richard Pierre Gelé |

Lotus Elan | Coventry Climax 1594cc S4 |

7 | Overheating (3hr) |

| DNF | P 4.0 |

58 (reserve) |

North American Racing Team | David Piper Jochen Rindt |

Ferrari 250 LM | Ferrari 3.3L V12 | 0 | Oil pipe (1hr) |

Did Not Start

edit| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNS | GT 2.0 |

36 | J-C Mosnier (private entrant) |

Jean-Claude Mosnier André de Cortanze |

Porsche 904/4 GTS | Porsche 1967cc F4 | practice accident |

| DNS | P 1.15 |

51 | Société des Automobiles Alpine |

Jacques Feret Pierre Orsini |

Alpine A110 M63 | Renault-Gordini 1149cc S4 |

practice accident |

| DNS | P 1.3 |

66 (reserve) | Lawrence Tune Engineering | Chris Spender Eamonn Donnelly |

Deep Sanderson 301 | BMC 1293cc S4 | practice accident |

| DNA | P 5.0 |

4 | Shelby-American Inc. | Ken Miles Bob Holbert |

Shelby Daytona Cobra Coupe | Ford 4.7L V8 | did not arrive |

| DNA | P 5.0 |

7 | E. Hugus (private entrant) |

Ed Hugus | Shelby Daytona Cobra Coupe | Ford 4.7L V8 | did not arrive |

| DNA | P 3.0 |

26 | Owen Racing Organisation | Graham Hill Richie Ginther |

Rover-BRM | Rover Turbine | withdrawn |

| DNA | P 2.5 |

28 | Automobili Turismo e Sport | Teodoro Zeccoli | ATS 2500 GT | ATS 2.5L V8 | arrived too late held at Customs[4] |

| DNA | P 1.15 |

61 (reserve) | Donald Healey Motor Company | Austin-Healey Sebring Sprite | BMC 1101cc S4 | did not practise | |

| DNP | GT 2.0 |

62 (reserve) | Racing Team Holland | Carel Godin de Beaufort Gerhard Mitter |

Porsche 904/4 GTS | Porsche 1967cc F4 | did not practise |

| DNP | GT 5.0 |

63 (reserve) | Société Chardonnet | Lloyd ‘Lucky’ Casner Jean Vincent |

AC Cobra | Ford 4.7L V8 | did not practise |

| DNP | GT 2.0 |

67 (reserve) | R.J.Lutz (private entrant) |

Roland Lutz Richard O’Steen |

Elva Courier Mk4 | MG 1798cc S4 | did not practise |

Class Winners

edit| Class | Prototype Winners |

Class | GT Winners | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prototype >5000 |

#1 Iso Grifo A3C | Noblet / Berney * | Grand Touring >5000 |

no entrants | |

| Prototype 5000 |

no finishers | Grand Touring 5000 |

#5 Shelby Daytona Cobra Coupe | Gurney / Bondurant * | |

| Prototype 4000 |

#20 Ferrari 275 P | Vaccarella / Guichet * | Grand Touring 4000 |

no finishers | |

| Prototype 3000 |

no entrants | Grand Touring 3000 |

#24 Ferrari 250 GTO | “Beurlys”/ Bianchi | |

| Prototype 2500 |

no entrants | Grand Touring 2500 |

no entrants | ||

| Prototype 2000 |

no finishers | Grand Touring 2000 |

#34 Porsche 904/4 GTS | Buchet / Ligier * | |

| Prototype 1600 |

no entrants | Grand Touring 1600 |

#57 Alfa Romeo Giulia TZ | Bussinello / Deserti * | |

| Prototype 1300 |

no finishers | Grand Touring 1300 |

#43 Lotus Elite | Hunt / Wagstaff | |

| Prototype 1150 |

#46 Alpine A110 M64 | Delageneste / Morrogh * | Grand Touring 1150 |

#52 Bonnet Aérodjet LM6 | Farjon / Lelong |

- Note: setting a new Distance Record.

Index of Thermal Efficiency

edit- Note: Only the top ten positions are included in this set of standings.

Index of Performance

editTaken from Moity's book.[42]

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P 4.0 |

20 | SpA Ferrari SEFAC | Nino Vaccarella Jean Guichet |

Ferrari 275 P | 1.262 |

| 2 | P 4.0 |

14 | Maranello Concessionaires | Graham Hill Jo Bonnier |

Ferrari 330 P | 1.227 |

| 3 | GT 2.0 |

34 | Auguste Veuillet | Robert Buchet Guy Ligier |

Porsche 904/4 GTS | 1.224 |

| 4 | GT 3.0 |

24 | Equipe Nationale Belge | Lucien Bianchi “Beurlys” (Jean Blaton) |

Ferrari 250 GTO | 1.212 |

| 5= | P 1.15 |

59 (reserve) |

Société des Automobiles Alpine |

Roger Masson Teodoro Zeccoli |

Alpine A110 M63B | 1.207 |

| 5= | GT 2.0 |

33 | Racing Team Holland | Ben Pon Henk van Zalinge |

Porsche 904/4 GTS | 1.207 |

| 7 | P 4.0 |

19 | SpA Ferrari SEFAC | John Surtees Lorenzo Bandini |

Ferrari 330 P | 1.203 |

| 8 | P 1.15 |

46 | Société des Automobiles Alpine |

Roger Delageneste Henry Morrogh |

Alpine A110 M64 | 1.202 |

| 9 | GT 1.6 |

57 | Scuderia St. Ambroeus | Roberto Bussinello Bruno Deserti |

Alfa Romeo Giulia TZ | 1.200 |

| 10 | GT 3.0 |

25 | Maranello Concessionaires | Innes Ireland Tony Maggs |

Ferrari 250 GTO | 1.193 |

- Note: Only the top ten positions are included in this set of standings. A score of 1.00 means meeting the minimum distance for the car, and a higher score is exceeding the nominal target distance.

Statistics

editTaken from Quentin Spurring's book, officially licensed by the ACO

- Fastest Lap in practice – Tonda Doge Bizzarrini 5300 GT Strada – 3m 42.0s; 218.29 km/h (135.64 mph)

- Fastest Lap – Tonda Doge Bizzarrini 5300 GT Strada – 3:49.2secs; 211.43 km/h (131.38 mph)

- Distance – 4,695.31 km (2,917.53 mi)

- Winner's Average Speed – 195.64 km/h (121.57 mph)

- Attendance – 350 000[43]

Challenge Mondial de Vitesse et Endurance Standings

edit| Pos | Manufacturer | Points |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bizzarrini | 54 |

| 2 | Porsche | 22 |

| 3 | AC-Ford | 13 |

| 4 | Alfa Romeo | 4 |

- Citations

- ^ a b c Clausager 1982, p.129

- ^ a b Clarke 2009, p.130: Autocar Jun26 1964

- ^ a b c d e f Spurring 2010, p.140

- ^ a b c d e Moity 1974, p.97

- ^ a b Clarke 2009, p.129-30: Autosport Jun19 1964

- ^ a b c d e Spurring 2010, p.142-3

- ^ Laban 2001, p.146

- ^ Fox 1973, p.188

- ^ Fox 1973, p.190

- ^ a b c Spurring 2010, p.145-7

- ^ a b c Spurring 2010, p.157

- ^ a b Spurring 2010, p.154

- ^ a b c d e Spurring 2010, p.152

- ^ a b Spurring 2010, p.159

- ^ a b Spurring 2010, p.160

- ^ a b Spurring 2010, p.148

- ^ a b Spurring 2010, p.163

- ^ a b Spurring 2010, p.155

- ^ a b Spurring 2010, p.166

- ^ a b c Spurring 2010, p.165

- ^ a b c Spurring 2010, p.171

- ^ a b Laban 2001, p.147

- ^ a b Fox 1973, p.195

- ^ Spurring 2010, p.113

- ^ a b c Clarke 2009, p.132: Autocar Jun26 1964

- ^ Spurring 2010, p.169

- ^ a b Clarke 2009, p.135: Autocar Jun26 1964

- ^ a b c Clarke 2009, p.136: Autocar Jun26 1964

- ^ Clarke 2009, p.142: Road & Track Sept 1964

- ^ a b Spurring 2010, p.158

- ^ a b c d e f Clarke 2009, p.138: Autocar Jun26 1964

- ^ "Lionel Yvonnick". Motorsport Memorial. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ^ "Lionel Yvonnick". Motorsport Memorial. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ^ "Lionel Yvonnick". Motorsport Memorial. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ^ Spurring 2010, p.151

- ^ a b Clarke 2009, p.144: Road & Track Sep 1964

- ^ a b c Clarke 2009, p.139: Autocar Jun26 1964

- ^ Spurring 2010, p.164

- ^ "Peter Lindner". Motorsport Memorial. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- ^ "Carel Godin de Beaufort". Motorsport Memorial. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- ^ Spurring 2010, p.2

- ^ Moity 1974, p.172

- ^ "24 Heures du Mans". Racing Sports Cars. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

References

edit- Armstrong, Douglas – English editor (1965) Automobile Year #12 1964-65 Lausanne: Edita S.A.

- Clarke, R.M. - editor (2009) Le Mans 'The Ferrari Years 1958-1965' Cobham, Surrey: Brooklands Books ISBN 1-85520-372-3

- Clausager, Anders (1982) Le Mans London: Arthur Barker Ltd ISBN 0-213-16846-4

- Fox, Charles (1973) The Great Racing Cars & Drivers London: Octopus Books Ltd ISBN 978-0-7064-0213-1

- Laban, Brian (2001) Le Mans 24 Hours London: Virgin Books ISBN 1-85227-971-0

- Moity, Christian (1974) The Le Mans 24 Hour Race 1949-1973 Radnor, Pennsylvania: Chilton Book Co ISBN 0-8019-6290-0

- Spurring, Quentin (2010) Le Mans 1960-69 Yeovil, Somerset: Haynes Publishing ISBN 978-1-84425-584-9

External links

edit- Racing Sports Cars – Le Mans 24 Hours 1964 entries, results, technical detail. Retrieved 2 February 2018

- Le Mans History – Le Mans History, hour-by-hour (incl. pictures, YouTube links). Retrieved 2 February 2018

- Sportscars.tv – race commentary. Retrieved 14 December 2017

- World Sports Racing Prototypes – results, reserve entries & chassis numbers. Retrieved 2 February 2018

- Team Dan – results & reserve entries, explaining driver listings. As archived at web.archive.org

- Unique Cars & Parts – results & reserve entries. Retrieved 2 February 2018

- Formula 2 – Le Mans 1964 results & reserve entries. Retrieved 2 February 2018

- Motorsport Memorial – deaths in motorsport events. Retrieved 12 February 2018

- YouTube – 10min colour film looking at the American entries. Retrieved 2 February 2018

- YouTube – 3min colour footage. Retrieved 2 February 2018

- YouTube – 4min colour film about the new GT40. Retrieved 2 February 2018

- YouTube – 4min black/white film (Italian coverage). Retrieved 2 February 2018