Adiponectin (also referred to as GBP-28, apM1, AdipoQ and Acrp30) is a protein hormone and adipokine, which is involved in regulating glucose levels and fatty acid breakdown.[5][6] In humans, it is encoded by the ADIPOQ gene and is produced primarily in adipose tissue, but also in muscle and even in the brain.[7][8]

Structure

editAdiponectin is a 244-amino-acid-long polypeptide (protein). It has four distinct regions: The first is a short signal sequence that targets the hormone for secretion outside the cell; next is a short region that varies between species; the third is a 65-amino acid region with similarity to collagenous proteins; the last is a globular domain. Overall, this protein shows similarity to the complement 1Q factors (C1Q), but when the three-dimensional structure of the globular region was determined, a striking similarity to TNFα was observed, despite unrelated protein sequences.[9]

Function

editAdiponectin is a protein hormone that modulates a number of metabolic processes, including glucose regulation and fatty acid oxidation.[10][11][12] Adiponectin is secreted from adipose tissue (and also from the placenta in pregnancy[13]) into the bloodstream and is very abundant in plasma relative to many hormones. High adiponectin levels correlate with a lower risk of diabetes mellitus type 2.[14] Plasma levels of adiponectin are lower in obese subjects than in lean subjects.[15] Many studies have found adiponectin to be inversely correlated with body mass index in patient populations.[16] However, a meta analysis was not able to confirm this association in healthy adults.[17] Circulating adiponectin concentrations increase during caloric restriction in animals and humans, such as in patients with anorexia nervosa. Furthermore, a recent study suggests that adipose tissue within bone marrow, which increases during caloric restriction, contributes to elevated circulating adiponectin in this context.[18]

Transgenic mice with increased adiponectin show reduced adipocyte differentiation and increased energy expenditure associated with mitochondrial uncoupling.[19] The hormone plays a role in the suppression of the metabolic derangements that may result in type 2 diabetes,[16] obesity, atherosclerosis,[12] non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and an independent risk factor for metabolic syndrome.[20] Adiponectin in combination with leptin has been shown to completely reverse insulin resistance in mice.[21] Adiponectin enhances insulin sensitivity primarily though regulation of fatty acid oxidation and suppression of hepatic glucose production .[22]

Adiponectin is secreted into the bloodstream, where it accounts for about 0.01% of all plasma protein at around 5-10 μg/mL. In adults, plasma concentrations are higher in females than males, and are reduced in diabetics compared to nondiabetics. Weight reduction significantly increases circulating concentrations.[23]

Adiponectin automatically self-associates into larger structures. Initially, three adiponectin molecules bind together to form a homotrimer. The trimers continue to self-associate and form hexamers or dodecamers. Like the plasma concentration, the relative levels of the higher-order structures are sexually dimorphic, where females have increased proportions of the high-molecular-weight forms. Recent studies showed that the high-molecular-weight form may be the most biologically active form regarding glucose homeostasis.[15] High-molecular-weight adiponectin was further found to be associated with a lower risk of diabetes with similar magnitude of association as total adiponectin.[24] However, coronary artery disease has been found to be positively associated with high molecular weight adiponectin, but not with low molecular weight adiponectin.[25]

Adiponectin exerts some of its weight-reduction effects via the brain. This is similar to the action of leptin;[26] adiponectin and leptin can act synergistically.

Adiponectin promoted synaptic and memory function in the brain.[27] Humans with lower levels of adiponectin have reduced cognitive function.[27]

Receptors

editAdiponectin binds to a number of receptors. So far, two receptors have been identified with homology to G protein-coupled receptors, and one receptor similar to the cadherin family:[28][29]

- Adiponectin receptor 1 (AdipoR1)

- Adiponectin receptor 2 (AdipoR2)

- T-cadherin - CDH13

These have distinct tissue specificities within the body and have different affinities to the various forms of adiponectin. AdipoR1 is enriched in skeletal muscle, whereas AdipoR2 is enriched in liver.[8] Six months of exercise has been shown in rats to double muscle AdipoR1.[8]

The receptors affect the downstream target AMP kinase, an important cellular metabolic rate control point. Expression of the receptors is correlated with insulin levels, as well as reduced in mouse models of diabetes, particularly in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue.[30][31]

In 2016, the University of Tokyo announced that it would launch an investigation into claims of fabrication of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 identification data, as accused by an anonymous person/group called Ordinary_researchers.[32]

Discovery

editAdiponectin was first characterised in 1995 in differentiating 3T3-L1 adipocytes (Scherer PE et al.).[33] In 1996 it was characterised in mice as the mRNA transcript most highly expressed in adipocytes.[7] In 2007, adiponectin was identified as a transcript highly expressed in preadipocytes[34] (precursors of fat cells) differentiating into adipocytes.[34][35]

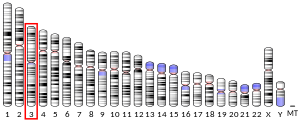

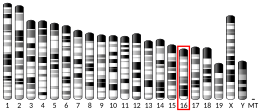

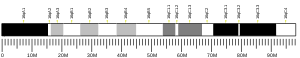

The human homologue was identified as the most abundant transcript in adipose tissue. Contrary to expectations, despite being produced in adipose tissue, adiponectin was found to be decreased in obesity.[12][16][26][11] This downregulation has not been fully explained. The gene was localised to chromosome 3q27, a region highlighted as affecting genetic susceptibility to type 2 diabetes and obesity. Supplementation by differing forms of adiponectin was able to improve insulin control, blood glucose and triglyceride levels in mouse models.

The gene was investigated for variants that predispose to type 2 diabetes.[26][34][36][37][38][39] Several single nucleotide polymorphisms in the coding region and surrounding sequence were identified from several different populations, with varying prevalences, degrees of association and strength of effect on type 2 diabetes. Berberine, an isoquinoline alkaloid, has been shown to increase adiponectin expression,[40] which partly explains its beneficial effects on metabolic disturbances. Mice fed the omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) have shown increased plasma adiponectin.[41] Curcumin, capsaicin, gingerol, and catechins have also been found to increase adiponectin expression.[42]

Phylogenetic distribution includes expression in birds[43] and fish.[44]

Metabolic

editAdiponectin effects:

- glucose flux

- decreased gluconeogenesis

- increased glucose uptake[12][26][37]

- lipid catabolism[37]

- β-oxidation[26]

- triglyceride clearance[26]

- protection from endothelial dysfunction (important facet of atherosclerotic formation)

- insulin sensitivity

- weight loss

- control of energy metabolism.[37]

- upregulation of uncoupling proteins[19]

- reduction of TNF-alpha

- promotion of reverse cholesterol transport[45]

Regulation of adiponectin

Hypoadiponectinemia

editA low level of adiponectin is an independent risk factor for developing:

Other

editLower levels of adiponectin are associated with ADHD in adults.[48]

Adiponectin levels were found to be increased in rheumatoid arthritis patients responding to DMARDs or TNF inhibitor therapy.[49]

A low adiponectin to leptin ratio has been found in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia compared to healthy controls.[50]

Exercise induced release of adiponectin increased hippocampal growth and led to antidepressive symptoms in mice.[51]

Several studies have found a positive correlation in caffeine consumption and increased adiponectin levels, although the mechanism for this is unknown and requires more research.[52]

As a medication target

editCirculating levels of adiponectin can indirectly be increased through lifestyle modifications and certain medications such as statins.[53]

A small molecule adiponectin receptor AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 agonist, AdipoRon, has been reported.[54] In 2016, the University of Tokyo announced it was launching an investigation into anonymously made claims of fabricated and falsified data on AdipoR1, AdipoR2, and AdipoRon.[32]

Extracts of sweet potatoes have been reported to increase levels of adiponectin and thereby improve glycemic control in humans.[55] However, a systematic review concluded there is insufficient evidence to support the consumption of sweet potatoes to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus.[56]

Adiponectin is apparently able to cross the blood-brain-barrier.[51] However, conflicting data on this issue exist.[57] Adiponectin has a half-life of 2.5 hours in humans.[58]

References

edit- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000181092 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000022878 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Ellulu MS, Patimah I, Khaza'ai H, Rahmat A, Abed Y (2017-06-08). "Obesity and inflammation the linking mechanism and the complications". Archives of Medical Science. 13 (4): 851–863. doi:10.5114/aoms.2016.58928. ISSN 1734-1922. PMC 5507106. PMID 28721154.

- ^ Amerikanou C, Kaliora AC, Gioxari A (2021-12-01). "The efficacy of Panax ginseng in obesity and the related metabolic disorders". Pharmacological Research - Modern Chinese Medicine. 1: 100013. doi:10.1016/j.prmcm.2021.100013. ISSN 2667-1425.

- ^ a b Maeda K, Okubo K, Shimomura I, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y, Matsubara K (April 1996). "cDNA cloning and expression of a novel adipose specific collagen-like factor, apM1 (AdiPose Most abundant Gene transcript 1)". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 221 (2): 286–289. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1996.0587. PMID 8619847.

- ^ a b c Martinez-Huenchullan SF, Tam CS, Ban LA, Ehrenfeld-Slater P, Mclennan SV, Twigg SM (January 2020). "Skeletal muscle adiponectin induction in obesity and exercise". Metabolism. 102: 154008. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2019.154008. PMID 31706980.

- ^ Shapiro L, Scherer PE (March 1998). "The crystal structure of a complement-1q family protein suggests an evolutionary link to tumor necrosis factor". Current Biology. 8 (6): 335–338. Bibcode:1998CBio....8..335S. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(98)70133-2. PMID 9512423. S2CID 14287212.

- ^ a b c Ghoshal K, et al. (June 2021). "Adiponectin Genetic Variant and Expression Coupled with Lipid Peroxidation Reveal New Signatures in Diabetic Dyslipidemia". Biochemical Genetics. 59 (3): 781–798. doi:10.1007/s10528-021-10030-5. PMID 33543406. S2CID 231817353.

- ^ a b c d Ghoshal K, Bhattacharyya M (February 2015). "Adiponectin: Probe of the molecular paradigm associating diabetes and obesity". World J Diabetes. 15 (6(1)): 151–166. doi:10.4239/wjd.v6.i1.151. PMC 4317307. PMID 25685286.

- ^ a b c d Díez JJ, Iglesias P (March 2003). "The role of the novel adipocyte-derived hormone adiponectin in human disease". European Journal of Endocrinology. 148 (3): 293–300. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1480293. PMID 12611609.

- ^ Chen J, Tan B, Karteris E, Zervou S, Digby J, Hillhouse EW, et al. (June 2006). "Secretion of adiponectin by human placenta: differential modulation of adiponectin and its receptors by cytokines". Diabetologia. 49 (6): 1292–1302. doi:10.1007/s00125-006-0194-7. PMID 16570162.

- ^ Li S, Shin HJ, Ding EL, van Dam RM (July 2009). "Adiponectin levels and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA. 302 (2): 179–188. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.976. PMID 19584347.

- ^ a b Oh DK, Ciaraldi T, Henry RR (May 2007). "Adiponectin in health and disease". Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism. 9 (3): 282–289. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2006.00610.x. PMID 17391153. S2CID 23270116.

- ^ a b c Ukkola O, Santaniemi M (November 2002). "Adiponectin: a link between excess adiposity and associated comorbidities?". Journal of Molecular Medicine. 80 (11): 696–702. doi:10.1007/s00109-002-0378-7. PMID 12436346. S2CID 23209903.

- ^ Kuo SM, Halpern MM (December 2011). "Lack of association between body mass index and plasma adiponectin levels in healthy adults". International Journal of Obesity. 35 (12): 1487–1494. doi:10.1038/ijo.2011.20. PMID 21364526.

- ^ Cawthorn WP, Scheller EL, Learman BS, Parlee SD, Simon BR, Mori H, et al. (August 2014). "Bone marrow adipose tissue is an endocrine organ that contributes to increased circulating adiponectin during caloric restriction". Cell Metabolism. 20 (2): 368–375. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2014.06.003. PMC 4126847. PMID 24998914.

- ^ a b Bauche IB, El Mkadem SA, Pottier AM, Senou M, Many MC, Rezsohazy R, et al. (April 2007). "Overexpression of adiponectin targeted to adipose tissue in transgenic mice: impaired adipocyte differentiation". Endocrinology. 148 (4): 1539–1549. doi:10.1210/en.2006-0838. PMID 17204560.

- ^ a b Renaldi O, Pramono B, Sinorita H, Purnomo LB, Asdie RH, Asdie AH (January 2009). "Hypoadiponectinemia: a risk factor for metabolic syndrome". Acta Medica Indonesiana. 41 (1): 20–24. PMID 19258676.

- ^ Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Waki H, Terauchi Y, Kubota N, Hara K, et al. (August 2001). "The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity". Nature Medicine. 7 (8): 941–946. doi:10.1038/90984. PMID 11479627. S2CID 31308235.

- ^ Fisman EZ, Tenenbaum A (June 2014). "Adiponectin: a manifold therapeutic target for metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and coronary disease?". Cardiovascular Diabetology. 13 (1): 103. doi:10.1186/1475-2840-13-103. PMC 4230016. PMID 24957699.

- ^ Coppola A, Marfella R, Coppola L, Tagliamonte E, Fontana D, Liguori E, et al. (May 2009). "Effect of weight loss on coronary circulation and adiponectin levels in obese women". International Journal of Cardiology. 134 (3): 414–416. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.12.087. PMID 18378021.

- ^ Zhu N, Pankow JS, Ballantyne CM, Couper D, Hoogeveen RC, Pereira M, et al. (November 2010). "High-molecular-weight adiponectin and the risk of type 2 diabetes in the ARIC study". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 95 (11): 5097–5104. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-0716. PMC 2968724. PMID 20719834.

- ^ Rizza S, Gigli F, Galli A, Micchelini B, Lauro D, Lauro R, Federici M (April 2010). "Adiponectin isoforms in elderly patients with or without coronary artery disease". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 58 (4): 702–706. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02773.x. PMID 20398150. S2CID 30291450.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nedvídková J, Smitka K, Kopský V, Hainer V (2005). "Adiponectin, an adipocyte-derived protein" (PDF). Physiological Research. 54 (2): 133–140. doi:10.33549/physiolres.930600. PMID 15544426. S2CID 24141809.

- ^ a b Forny-Germano L, De Felice FG, Vieira MN (2019). "The Role of Leptin and Adiponectin in Obesity-Associated Cognitive Decline and Alzheimer's Disease". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 12: 1027. doi:10.3389/fnins.2018.01027. PMC 6340072. PMID 30692905.

- ^ Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Ito Y, Tsuchida A, Yokomizo T, Kita S, et al. (June 2003). "Cloning of adiponectin receptors that mediate antidiabetic metabolic effects". Nature. 423 (6941): 762–769. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..762Y. doi:10.1038/nature01705. PMID 12802337. S2CID 52860797.

- ^ Hug C, Wang J, Ahmad NS, Bogan JS, Tsao TS, Lodish HF (July 2004). "T-cadherin is a receptor for hexameric and high-molecular-weight forms of Acrp30/adiponectin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (28): 10308–10313. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10110308H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0403382101. PMC 478568. PMID 15210937.

- ^ Fang X, Sweeney G (November 2006). "Mechanisms regulating energy metabolism by adiponectin in obesity and diabetes". Biochemical Society Transactions. 34 (Pt 5): 798–801. doi:10.1042/BST0340798. PMID 17052201. S2CID 1473301.

- ^ Bonnard C, Durand A, Vidal H, Rieusset J (February 2008). "Changes in adiponectin, its receptors and AMPK activity in tissues of diet-induced diabetic mice". Diabetes & Metabolism. 34 (1): 52–61. doi:10.1016/j.diabet.2007.09.006. PMID 18222103.

- ^ a b University of Tokyo to investigate data manipulation charges against six prominent research groups ScienceInsider, Dennis Normile, Sep 20, 2016

- ^ Scherer PE, Williams S, Fogliano M, Baldini G, Lodish HF (November 1995). "A novel serum protein similar to C1q, produced exclusively in adipocytes". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 270 (45): 26746–26749. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.45.26746. PMID 7592907.

- ^ a b c d Lara-Castro C, Fu Y, Chung BH, Garvey WT (June 2007). "Adiponectin and the metabolic syndrome: mechanisms mediating risk for metabolic and cardiovascular disease". Current Opinion in Lipidology. 18 (3): 263–270. doi:10.1097/MOL.0b013e32814a645f. PMID 17495599. S2CID 20799218.

- ^ Matsuzawa Y, Funahashi T, Kihara S, Shimomura I (January 2004). "Adiponectin and metabolic syndrome". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 24 (1): 29–33. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000099786.99623.EF. PMID 14551151.

- ^ a b Hara K, Yamauchi T, Kadowaki T (April 2005). "Adiponectin: an adipokine linking adipocytes and type 2 diabetes in humans". Current Diabetes Reports. 5 (2): 136–140. doi:10.1007/s11892-005-0041-0. PMID 15794918. S2CID 23664493.

- ^ a b c d Vasseur F, Leprêtre F, Lacquemant C, Froguel P (April 2003). "The genetics of adiponectin". Current Diabetes Reports. 3 (2): 151–158. doi:10.1007/s11892-003-0039-4. PMID 12728641. S2CID 21611611.

- ^ a b Hug C, Lodish HF (April 2005). "The role of the adipocyte hormone adiponectin in cardiovascular disease". Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 5 (2): 129–134. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2005.01.001. PMID 15780820.

- ^ a b Vasseur F, Meyre D, Froguel P (November 2006). "Adiponectin, type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome: lessons from human genetic studies". Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine. 8 (27): 1–12. doi:10.1017/S1462399406000147. PMID 17112391. S2CID 20732833.

- ^ Choi BH, Kim YH, Ahn IS, Ha JH, Byun JM, Do MS (2009). "The inhibition of inflammatory molecule expression on 3T3-L1 adipocytes by berberine is not mediated by leptin signaling". Nutrition Research and Practice. 3 (2): 84–88. doi:10.4162/nrp.2009.3.2.84. PMC 2788178. PMID 20016706.

- ^ Grimshaw CE, Matthews DA, Varughese KI, Skinner M, Xuong NH, Bray T, et al. (August 1992). "Characterization and nucleotide binding properties of a mutant dihydropteridine reductase containing an aspartate 37-isoleucine replacement". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 267 (22): 15334–15339. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)49538-0. PMID 1639779.

- ^ Nigro E, Scudiero O, Monaco ML, Palmieri A, Mazzarella G, Costagliola C, et al. (2014). "New insight into adiponectin role in obesity and obesity-related diseases". BioMed Research International. 2014: 658913. doi:10.1155/2014/658913. PMC 4109424. PMID 25110685.

- ^ Yuan J, Liu W, Liu ZL, Li N (2006). "cDNA cloning, genomic structure, chromosomal mapping and expression analysis of ADIPOQ (adiponectin) in chicken". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 112 (1–2): 148–151. doi:10.1159/000087527. PMID 16276104. S2CID 27327817.

- ^ Nishio S, Gibert Y, Bernard L, Brunet F, Triqueneaux G, Laudet V (June 2008). "Adiponectin and adiponectin receptor genes are coexpressed during zebrafish embryogenesis and regulated by food deprivation". Developmental Dynamics. 237 (6): 1682–1690. doi:10.1002/dvdy.21559. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30062852. PMID 18489000. S2CID 39211439.

- ^ Hafiane A, Gasbarrino K, Daskalopoulou SS (November 2019). "The role of adiponectin in cholesterol efflux and HDL biogenesis and metabolism". Metabolism. 100: 153953. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2019.153953. PMID 31377319. S2CID 203413137.

- ^ Liu M, Liu F (October 2012). "Up- and down-regulation of adiponectin expression and multimerization: mechanisms and therapeutic implication". Biochimie. 94 (10): 2126–2130. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2012.01.008. PMC 3542391. PMID 22342903.

- ^ Iwashima Y, Katsuya T, Ishikawa K, Ouchi N, Ohishi M, Sugimoto K, Fu Y, Motone M, Yamamoto K, Matsuo A, Ohashi K, Kihara S, Funahashi T, Rakugi H, Matsuzawa Y, Ogihara T (June 2004). "Hypoadiponectinemia Is an Independent Risk Factor for Hypertension". Hypertension. 43 (6): 1318–1323. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000129281.03801.4b. ISSN 0194-911X. PMID 15123570. S2CID 9952849.

- ^ Mavroconstanti T, Halmøy A, Haavik J (April 2014). "Decreased serum levels of adiponectin in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Psychiatry Research. 216 (1): 123–130. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.01.025. PMID 24559850. S2CID 14858659.

- ^ Kim KS, Choi HM, Ji HI, Song R, Yang HI, Lee SK, et al. (January 2014). "Serum adipokine levels in rheumatoid arthritis patients and their contributions to the resistance to treatment". Molecular Medicine Reports. 9 (1): 255–260. doi:10.3892/mmr.2013.1764. PMID 24173909.

- ^ Tonon F, Bella SD, Giudici F, Zerbato V, Segat L, Koncan R, et al. (2022-04-26). Salvador J (ed.). "Discriminatory Value of Adiponectin to Leptin Ratio for COVID-19 Pneumonia". International Journal of Endocrinology. 2022: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2022/9908450. ISSN 1687-8345. PMC 9072020. PMID 35529082.

- ^ a b Yau SY, Li A, Hoo RL, Ching YP, Christie BR, Lee TM, et al. (November 2014). "Physical exercise-induced hippocampal neurogenesis and antidepressant effects are mediated by the adipocyte hormone adiponectin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (44): 15810–15815. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11115810Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.1415219111. PMC 4226125. PMID 25331877.

- ^ Buscemi S, Marventano S, Antoci M, Cagnetti A, Castorina G, Galvano F, et al. (2016-08-01). "Coffee and metabolic impairment: An updated review of epidemiological studies". NFS Journal. 3: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.nfs.2016.02.001. hdl:10447/219127. ISSN 2352-3646.

- ^ Lim S, Quon MJ, Koh KK (April 2014). "Modulation of adiponectin as a potential therapeutic strategy". Atherosclerosis. 233 (2): 721–728. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.01.051. PMID 24603219.

- ^ Okada-Iwabu M, Yamauchi T, Iwabu M, Honma T, Hamagami K, Matsuda K, et al. (November 2013). "A small-molecule AdipoR agonist for type 2 diabetes and short life in obesity". Nature. 503 (7477): 493–499. Bibcode:2013Natur.503..493O. doi:10.1038/nature12656. PMID 24172895. S2CID 4447039.

- ^ Ludvik B, Hanefeld M, Pacini G (July 2008). "Improved metabolic control by Ipomoea batatas (Caiapo) is associated with increased adiponectin and decreased fibrinogen levels in type 2 diabetic subjects". Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism. 10 (7): 586–592. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00752.x. PMID 17645559. S2CID 30418587.

- ^ Ooi CP, Loke SC (September 2013). "Sweet potato for type 2 diabetes mellitus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (9): CD009128. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009128.pub3. PMC 6486146. PMID 24000051.

- ^ Spranger J, Verma S, Göhring I, Bobbert T, Seifert J, Sindler AL, et al. (January 2006). "Adiponectin does not cross the blood-brain barrier but modifies cytokine expression of brain endothelial cells". Diabetes. 55 (1): 141–147. doi:10.2337/diabetes.55.1.141. PMID 16380487.

- ^ Hoffstedt J, Arvidsson E, Sjölin E, Wåhlén K, Arner P (March 2004). "Adipose tissue adiponectin production and adiponectin serum concentration in human obesity and insulin resistance". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 89 (3): 1391–1396. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-031458. PMID 15001639.

External links

edit- Human ADIPOQ genome location and ADIPOQ gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: Q15848 (Human Adiponectin) at the PDBe-KB.

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: Q60994 (Mouse Adiponectin) at the PDBe-KB.