Changchun[a] is the capital and largest city of Jilin Province in China.[8] Lying in the center of the Songliao Plain, Changchun is administered as a sub-provincial city, comprising 7 districts, 1 county and 3 county-level cities.[9] According to the 2020 census of China, Changchun had a total population of 9,066,906 under its jurisdiction. The city's metro area, comprising 5 districts and 1 development area, had a population of 5,019,477 in 2020, as the Shuangyang and Jiutai districts are not urbanized yet.[3] It is one of the biggest cities in Northeast China, along with Shenyang, Dalian and Harbin.

Changchun

长春市 | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: panoramic view from Shengtai Plaza, panoramic view of Ji Tower, Former Manchukuo State Department, Statue on cultural square, Changchun Christian Church, Soviet martyr monument. | |

| Nickname: 北国春城 (Spring City of the Northern Country) | |

| |

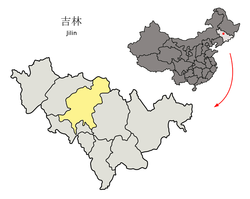

Location of Changchun City (yellow) in Jilin (light grey) and China | |

| Coordinates (Jilin People's Government): 43°53′49″N 125°19′34″E / 43.897°N 125.326°E | |

| Country | China |

| Province | Jilin |

| County-level divisions | 7 districts 2 county-level divisions 1 county |

| Incorporated (town) | 1889 |

| Incorporated (city) | 1932 |

| Municipal seat | Nanguan District |

| Government | |

| • Type | Sub-provincial city |

| • Body | Changchun Municipal People's Congress |

| • CCP Secretary | vacant as of March 2021[update] |

| • Congress Chairman | Wang Zhihou |

| • Mayor | Zhang Zhijun |

| • CPPCC Chairman | Qi Yuanfang |

| Area | |

| 24,734 km2 (9,550 sq mi) | |

| • Urban (2017)[2] | 1,855.00 km2 (716.22 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,855.00 km2 (716.22 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 222 m (730 ft) |

| Population (2020 census)[3] | |

| 9,066,906 | |

| • Density | 370/km2 (950/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 5,691,024 |

| • Urban density | 3,100/km2 (7,900/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 5,019,477 |

| • Metro density | 2,700/km2 (7,000/sq mi) |

| GDP[4] | |

| • Prefecture-level & Sub-provincial city | CN¥ 553 billion US$ 88.8 billion |

| • Per capita | CN¥ 73,324 US$ 11,773 |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (China Standard) |

| Postal code | 130000 |

| Area code | 0431 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-JL-01 |

| License plate prefixes | 吉A |

| Website | www.changchun.gov.cn |

| [5] | |

| Changchun | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Changchun" in Simplified Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 长春 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 長春 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Chángchūn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Long Spring" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hsinking | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 新京 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Xīnjīng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | New Capital | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu script | ᠴᠠᠨᡤᠴᠣᠨ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romanization | Cangcon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The name of the city means "long spring" in Chinese. Between 1932 and 1945, Changchun was renamed Xinjing (Chinese: 新京; pinyin: Xīnjīng; lit. 'new capital') or Hsinking by the Kwantung Army as it became the capital of the Imperial Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo, occupying modern Northeast China. After the foundation of the People's Republic of China in 1949, Changchun was established as the provincial capital of Jilin in 1954.

Known locally as China's "City of Automobiles",[10] Changchun is an important industrial base with a particular focus on the automotive sector.[11] Because of its key role in the domestic automobile industry, Changchun was sometimes referred to as the "Detroit of China."[12] Apart from this industrial aspect, Changchun is also one of four "National Garden Cities" awarded by the Ministry of Construction of P.R. China in 2001 due to its high urban greening rate.[10][failed verification]

Changchun is also one of the top 30 cities in the world by scientific research as tracked by the Nature Index according to the Nature Index 2024 Science Cities.[13] The city is home to several major universities, notably Jilin University and Northeast Normal University, members of China's prestigious universities in the Double First-Class Construction.

History

editEarly history

editChangchun was initially established on imperial decree as a small trading post and frontier village during the reign of the Jiaqing Emperor in the Qing dynasty. Trading activities mainly involved furs and other natural products during this period. In 1800, the Jiaqing Emperor selected a small village on the east bank of the Yitong River and named it "Changchun Ting".[14]

At the end of the 18th century peasants from overpopulated provinces such as Shandong and Hebei began to settle in the region. In 1889, the village was promoted into a city known as "Changchun Fu".[15]

Railway era

editIn May 1898, Changchun got its first railway station, located in Kuancheng, part of the railway from Harbin to Lüshun (the southern branch of the Chinese Eastern Railway), constructed by the Russian Empire.[16]

After Russia's loss of the southernmost section of this branch as a result of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, the Kuancheng station (Kuanchengtze, in contemporary spelling) became the last Russian station on this branch.[16] The next station just a short distance to the south—the new "Japanese" Changchun station—became the first station of the South Manchuria Railway,[17] which now owned all the tracks running farther south, to Lüshun, which they re-gauged to the standard gauge (after a short period of using the narrow Japanese 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge during the war).[18]

A special Russo-Japanese agreement of 1907 provided that Russian gauge tracks would continue from the "Russian" Kuancheng Station to the "Japanese" Changchun Station, and vice versa, tracks on the "gauge adapted by the South Manchuria Railway" (i.e. the standard gauge) would continue from Changchun Station to Kuancheng Station.[17]

An epidemic of pneumonic plague occurred in surrounding Manchuria from 1910 to 1911, known as the Manchurian plague.[19] It was the worst-ever recorded outbreak of pneumonic plague which was spread through the Trans-Manchurian railway from the border trade port of Manzhouli.[20] This turned out to be the beginning of the large pneumonic plague pandemic of Manchuria and Mongolia which ultimately claimed 60,000 victims.[21]

City planning and development from 1906 to 1931

editThe Treaty of Portsmouth formally ended the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05 and saw the transfer and assignment to the Empire of Japan in 1906 the railway between Changchun and Port Arthur, and all its branches.[22]

Having realized the strategic importance of Changchun's location with respect to Japan, China and Russia, the Japanese Government sent a group of planners and engineers to Changchun to determine the best site for a new railway station.[citation needed]

Without the consent of the Chinese Government, Japan purchased or seized from local farmers the land on which the Changchun Railway Station was to be constructed as the centre of the South Manchuria Railway Affiliated Areas (SMRAA).[23] In order to turn Changchun into the centre for extracting the agricultural and mineral resources of Manchuria, Japan developed a blueprint for Changchun and invested heavily in the construction of the city.[citation needed]

At the beginning of 1907, as the prelude to, and preparation for, the invasion and occupation of China, Japan initiated the planning programme of the SMRAA, which embodied distinctive colonial characteristics. The guiding ideology of the overall design was to build a high standard colonial city with sophisticated facilities, multiple functions and a large scale.[citation needed]

Accordingly, nearly ¥7 million on average was allocated on a year-by-year basis for urban planning and construction during the period 1907 to 1931.[24]

The comprehensive plan was to ensure the comfort required by Japanese employees on Manchurian Railways, build up Changchun into a base for Japanese control of the whole Manchuria in order to provide an effective counterweight to Russia in this area of China.[citation needed]

The city's role as a rail hub was underlined in its planning and construction, the main design concepts of which read as follows: under conventional grid pattern terms, two geoplagiotropic boulevards were newly carved eastward and westward from the grand square of the new railway station. The two helped form two intersections with the gridded prototypes, which led to two circles of South and West. The two sub-civic centres served as axes on which eight radial roads were blazed that took the shape of a sectoral structure.[citation needed]

At that time, the radial circles and the design concept of urban roads were quite advanced and scientific. It activated to great extent the serious urban landscapes as well as clearly identifying the traditional gridded pattern.[by whom?]

With the new Changchun railway station as its centre, the urban plan divided the SMRAA into various specified areas: residential quarters 15%, commerce 33%, grain depot 19%, factories 12%, public entertainment 9%, and administrative organs (including a Japanese garrison) 12%.[24] Each block provided the railway station with supporting and systematic services dependent on its own functions.

In the meantime, a comprehensive system of judiciary and military police was established which was totally independent of China. That accounted for the widespread nature of military facilities within the urban construction area of 3.967 km2 (1.532 sq mi), such as the railway garrison, the gendarmerie and the police department, with its 18 local police stations.[24]

Perceiving Changchun as a tabula rasa upon which to construct new and sweeping conceptions of the built environment, the Japanese used the city as a practical laboratory to create two distinct and idealized urban milieus, each appropriate to a particular era. From 1906 to 1931, Changchun served as a key railway town through which the Japanese orchestrated an informal empire. Between 1932 and 1945, the city became home to a grandiose new Asian capital. Yet, while the façades in the city and later the capital contrasted markedly, along with the attitudes of the state they upheld, the shifting styles of planning and architecture consistently attempted to represent Japanese rule as progressive, beneficent, and modern.[by whom?]

The development of Changchun, in addition to being driven by the railway system, suggested an important period of the Northeast modern architectural culture, reflecting Japanese urban design endeavours and revealing that county's ambition to invade and occupy China. Japanese architecture and culture had been widely applied to Manchukuo to highlight the special status of the Japanese puppet. Urban planning clearly stems from a culture, be it aggressive or creative. Changchun's planning and construction process serves as a good example.[by whom?]

Changchun expanded rapidly as the junction between of the Japanese-owned South Manchurian Railway and the Russian-owned Chinese Eastern Railway, remaining the break of gauge point between the Russian and standard gauges into the 1930s,[25]

Manchukuo and World War II

editOn 10 March 1932 the capital of Manchukuo, a Japan-controlled puppet state in Manchuria, was established in Changchun.[26] The city was then renamed Hsinking (Chinese: 新京; pinyin: Xīnjīng; Wade–Giles: Hsin-ching; Japanese:Shinkyō; literally "New Capital") on 13 March.[27] The Emperor Puyi resided in the Imperial Palace (Chinese: 帝宮; pinyin: Dì gōng) which is now the Museum of the Manchu State Imperial Palace. During the Manchukuo period, the region experienced harsh suppression, brutal warfare on the civilian population,[citation needed] forced conscription and labor and other Japanese sponsored government brutalities; at the same time a rapid industrialisation and militarisation took place. Hsinking was a well-planned city with broad avenues and modern public works. The city underwent rapid expansion in both its economy and infrastructure. Many of buildings built during the Japanese colonial era still stand today, including those of the Eight Major Bureaus of Manchukuo (Chinese: 八大部; pinyin: Bādà bù) as well as the Headquarters of the Japanese Kwantung Army.

Construction of Hsinking

editHsinking was the only Direct-controlled municipality (特别市) in Manchukuo after Harbin was incorporated into the jurisdiction of Binjiang Province.[28] In March 1932, the Inspection Division of South Manchuria Railway started to draw up the Metropolitan Plan of Great Hsinking (simplified Chinese: 大新京都市计画; traditional Chinese: 大新京都市計畫; pinyin: Dà xīn jīngdū shì jìhuà). The Bureau of capital construction (国都建设局; 國都建設局; Guódū jiànshè jú) which was directly under the control of State Council of Manchukuo was established to take complete responsibility of the formulation and the implementation of the plan.[29] Kuniaki Koiso, the Chief of Staff of the Kwantung Army, and Yasuji Okamura, the Vice Chief-of-Staff, finalized the plan of a 200 km2 (77 sq mi) construction area. The Metropolitan Plan of Great Hsinking was influenced by the renovation plan of Paris in the 19th century, the garden city movement, and theories of American cities' planning and design in the 1920s. The city development plan included extensive tree planting. By 1934 Hsinking was known as the Forest Capital with Jingyuetan Park built, which is now China's largest Plantation and a AAAA-rated recreational area.[30]

In accordance with the Metropolitan Plan of Great Hsinking, the area of publicly shared land (including the Imperial Palace, government offices, roads, parks and athletic grounds) in Hsinking was 47 km2 (18 sq mi), whilst the area of residential, commercial and industrial developments was planned to be 53 km2 (20 sq mi).[31] However, Hsinking's population exceeded the prediction of 500,000 by 1940. In 1941, the Capital Construction Bureau modified the original plan, which expanded the urban area to 160 km2 (62 sq mi). The new plan also focused on the construction of satellite towns around the city with a planning of 200 m2 (2,200 sq ft) land per capita.[29] Because the effects of war, the Metropolitan Plan of Great Hsinking remained unfinished. By 1944, the built up urban area of Hsinking reached 80 km2 (31 sq mi), while the area used for greening reached 70.7 km2 (27.3 sq mi). As Hsinking's city orientation was the administrative center and military commanding center, land for military use exceeded the originally planned figure of 9 percent, while only light manufacturing including packing industry, cigarette industry and paper-making had been developed during this period. Japanese force also controlled Hsinking's police system, instead of Manchukuo government.[32] Major officers of Hsinking police were all ethnic Japanese.[33]

The population of Hsinking also experienced rapid growth after being established as the capital of Manchukuo. According to the census in 1934 taken by the police agency, the city's municipal area had 141,712 inhabitants.[34] By 1944 the city's population had risen to 863,607,[35] with 153,614 Japanese settlers. This population made Hsinking the third largest metropolitan city in Manchukuo after Mukden and Harbin, as the metropolitan mainly focused on military and political function.[36]

Japanese chemical warfare agents

editIn 1936, the Imperial Japanese Army established Unit 100 to develop plague biological weapons, although the declared purpose of Unit 100 was to conduct research about diseases originating from animals.[37] During the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) and World War II the headquarters of Unit 100 ("Wakamatsu Unit") was located in downtown Hsinking, under command of veterinarian Yujiro Wakamatsu.[38] This facility was involved in research of animal vaccines to protect Japanese resources, and, especially, biological-warfare. Diseases were tested for use against Soviet and Chinese horses and other livestock. In addition to these tests, Unit 100 ran a bacteria factory to produce the pathogens needed by other units. Biological sabotage testing was also handled at this facility: everything from poisons to chemical crop destruction.

Siege of Changchun

editOn 20 August 1945 the city was captured by the Soviet Red Army and renamed Changchun.[39] The Russians maintained a presence in the city during the Soviet occupation of Manchuria until 1946.

National Revolutionary Army forces under Zheng Dongguo occupied the city in 1946, but were unable to hold the countryside against Lin Biao's People's Liberation Army forces during the Chinese Civil War. The city fell to the Chinese Communist Party in 1948 after the five-month Siege of Changchun, and the communist victory was a turning point which allowed an offensive to capture the remainder of Mainland China.[40] Between 10 and 30 percent[41] of the civilian population starved to death under the siege; estimates range from 150,000[42] to 330,000.[43] As of 2015[update] the PRC government avoids all mention of the siege.[44]

People's Republic

editRenamed Changchun by the People's Republic of China government, it became the capital of Jilin in 1954. The Changchun Film Studio is also one of the remaining film studios of the era. Changchun Film Festival has become a unique gala for film industries since 1992.[45]

From the 1950s, Changchun was designated to become a center for China's automotive industry. Construction of the First Automobile Works (FAW) began in 1953[46] and production of the Jiefang CA-10 truck, based on the Soviet ZIS-150 started in 1956.[47] Soviet Union lent assistance during these early years, providing technical support, tooling, and production machinery.[46] In 1958, FAW introduced the famous Hongqi (Red Flag) limousines[47] This series of cars are billed as "the official car for minister-level officials".[48]

In 2002, the local television broadcast was hijacked by a small group of Falun Gong practitioners. These events were depicted in the documentary Eternal Spring.

Changchun hosted the 2007 Winter Asian Games.[49]

Geography

editChangchun lies in the middle portion of the Northeast China Plain. Its municipality area is located at latitude 43° 05′−45° 15′ N and longitude 124° 18′−127° 02' E. The total area of Changchun municipality is 20,571 km2 (7,943 sq mi), including metro areas of 2,583 square kilometres (997 sq mi), and a city proper area of 159 km2 (61 sq mi). The city is situated at a moderate elevation, ranging from 250 to 350 metres (820 to 1,150 ft) within its administrative region.[1] In the eastern portion of the city, there lies a small area of low mountains, with the Laodaodong Mountain, which has an altitude of 711 meters, being the highest. The city is also situated at the crisscross point of the third east–westward "Europe-Asia Continental Bridge".[citation needed] Changchun prefecture is dotted with 222 rivers and lakes. The Yitong River, a small tributary of the Songhua River, runs through the city proper.

Climate

editChangchun has a four-season, monsoon-influenced, humid continental climate (Köppen Dwa). Winters are long (lasting from November to March), cold, and windy, but dry, due to the influence of the Siberian anticyclone, with a January mean temperature of −14.3 °C (6.3 °F). Spring and autumn are somewhat short transitional periods, with some precipitation, but are usually dry and windy. Summers are hot and humid, with a prevailing southeasterly wind due to the East Asian monsoon; July averages 23.7 °C (74.7 °F).[50] Snow is usually light during the winter, and annual rainfall is heavily concentrated from June to August. With monthly percent possible sunshine ranging from 49 percent in July to 69 percent in February, a typical year will see around 2,597 hours of sunshine,[50] and a frost-free period of 140 to 150 days. Extreme temperatures have ranged from −36.5 °C (−34 °F) to 38.0 °C (100 °F).[51]

| Climate data for Changchun (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1951–2018) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 4.6 (40.3) |

14.5 (58.1) |

23.4 (74.1) |

31.9 (89.4) |

35.2 (95.4) |

36.7 (98.1) |

38.0 (100.4) |

35.6 (96.1) |

30.6 (87.1) |

27.8 (82.0) |

20.7 (69.3) |

11.7 (53.1) |

38.0 (100.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −9.3 (15.3) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

4.5 (40.1) |

14.8 (58.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

26.5 (79.7) |

28.1 (82.6) |

26.9 (80.4) |

22.3 (72.1) |

13.7 (56.7) |

2.0 (35.6) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

11.7 (53.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −14.3 (6.3) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

−1 (30) |

8.8 (47.8) |

16.2 (61.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

23.7 (74.7) |

22.3 (72.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

7.9 (46.2) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−11.8 (10.8) |

6.5 (43.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −18.6 (−1.5) |

−14.3 (6.3) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

3.0 (37.4) |

10.5 (50.9) |

16.3 (61.3) |

19.7 (67.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

11.2 (52.2) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

−15.9 (3.4) |

1.6 (35.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −36.5 (−33.7) |

−31.9 (−25.4) |

−27.7 (−17.9) |

−12.2 (10.0) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

4.5 (40.1) |

11.1 (52.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

−24.7 (−12.5) |

−33.2 (−27.8) |

−36.5 (−33.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 4.4 (0.17) |

6.1 (0.24) |

13.4 (0.53) |

22.0 (0.87) |

62.6 (2.46) |

102.1 (4.02) |

147.5 (5.81) |

131.6 (5.18) |

53.9 (2.12) |

24.6 (0.97) |

16.9 (0.67) |

8.2 (0.32) |

593.3 (23.36) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 5.1 | 4.4 | 5.6 | 6.5 | 11.0 | 13.5 | 13.4 | 12.3 | 8.1 | 6.8 | 6.1 | 6.5 | 99.3 |

| Average snowy days | 7.5 | 5.9 | 6.4 | 2.4 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.9 | 6.1 | 8.2 | 38.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66 | 57 | 51 | 44 | 50 | 63 | 75 | 76 | 65 | 59 | 62 | 67 | 61 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 180.9 | 203.7 | 236.9 | 238.1 | 253.5 | 245.4 | 229.0 | 235.3 | 236.8 | 210.4 | 167.7 | 159.1 | 2,596.8 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 62 | 69 | 64 | 59 | 55 | 53 | 49 | 55 | 64 | 62 | 59 | 58 | 59 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1: China Meteorological Administration[50][52][53] Weather China[51] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas[54] | |||||||||||||

Administrative divisions

editThe sub-provincial city of Changchun has direct jurisdiction over 7 districts, 3 county-level cities and 1 County:

| Map | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Simplified Chinese | Hanyu Pinyin | Population (2020 census) | Area (km2) | |||||

| City proper | |||||||||

| Chaoyang District | 朝阳区 | Cháoyáng Qū | 1,074,628 | 286.7 | |||||

| Nanguan District | 南关区 | Nánguān Qū | 1,066,422 | 529.7 | |||||

| Kuancheng District | 宽城区 | Kuānchéng Qū | 856,177 | 941.5 | |||||

| Erdao District | 二道区 | Èrdào Qū | 559,966 | 452 | |||||

| Luyuan District | 绿园区 | Lùyuán Qū | 1.002,672 | 492.6 | |||||

| Suburb | |||||||||

| Shuangyang District | 双阳区 | Shuāngyáng Qū | 335,723 | 1,677 | |||||

| Jiutai District | 九台区 | Jiǔtái Qū | 613,836 | 3368 | |||||

| Satellite cities | |||||||||

| Dehui | 德惠市 | Déhuì Shì | 635,476 | 2,984 | |||||

| Yushu | 榆树市 | Yúshù Shì | 836,098 | 4,749 | |||||

| Gongzhuling | 公主岭市 | Gōngzhǔlǐng Shì | 862,313 | 4,145 | |||||

| Rural | |||||||||

| Nong'an County | 农安县 | Nóng'ān Xiàn | 763,983 | 5,239 | |||||

Demographics

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1932 | 104,305 | — |

| 1934 | 160,381 | +53.8% |

| 1939 | 415,473 | +159.1% |

| 1944 | 863,607 | +107.9% |

| 1953 | 855,197 | −1.0% |

| 1964 | 4,221,445 | +393.6% |

| 1982 | 5,744,769 | +36.1% |

| 1990 | 6,421,956 | +11.8% |

| 2000 | 7,135,439 | +11.1% |

| 2010 | 7,677,089 | +7.6% |

| Population size may be affected by changes in administrative divisions. In 1958, 5 counties were put under Changchun's jurisdiction, increasing the total population to over 4 million. | ||

According to the Sixth China Census, the total population of the City of Changchun reached 7.677 million in 2010.[55] The statistics in 2011 estimated the total population to be 7.59 million. The birth rate was 6.08 per thousand and the death rate was 5.51 per thousand. The urban area had a population of 3.53 million people. In 2010 the sex ratio of the city population was 102.10 males to 100 females.[55]

Ethnic groups

editAs in most of Northeastern China the ethnic makeup of Changchun is predominantly Han nationality (96.57 percent), with several other minority nationalities.[56]

| Ethnicity | Population[citation needed] | Percentage[citation needed] |

|---|---|---|

| Han | 6,883,310 | 96.47% |

| Manchu | 142,998 | 2.0% |

| Korean | 49,588 | 0.69% |

| Hui | 43,692 | 0.61% |

| Mongol | 11,106 | 0.16% |

| Xibe | 685 | 0.01% |

| Zhuang | 533 | 0.01% |

| Miao | 522 | 0.01% |

| Other | 3,005 | 0.04% |

Culture

editDialect

editThe most commonly spoken dialect in Changchun is the Northeastern Mandarin, which is originated from the mix of several languages spoken by immigrants from Hebei and Shandong. Then, after the PRC was established, the rapid economic growth in Changchun attracted a huge number of immigrants from various places, so the northeastern dialect spoken in urban areas of Changchun is closer to the Mandarin Chinese than the in rural areas because the immigrants had a great impact on the northeastern dialect spoken in urban areas.[57]

Religion

editChangchun has four major religions: Buddhism, Taoism, Christianity, and Islam. There are 396 government-approved places for religious activities and worship services.[57]

The temples in Changchun include Changchun Wanshou Temple, Baoguo Prajna Temple, Baiguo Xinglong Temple, Pumen Temple, Big Buddha Temple, Changchun Temple, Changchun Catholic Church, Changchun West Wuma Road Christian Church, and Changchun City Mosque.[58]

Shamanism had been circulated in Northeast China during ancient times and was believed by many Manchus. Now the shamanism and the study of it have become an important cultural heritage of the region.[59]

Places of interest

editJilin Provincial Museum, a national first-grade museum, is located in Changchun. The museum was moved to Changchun from Jilin City after the transfer of the provincial government seat.[60] It was originally located in the centre of the old town, but, after nine years of construction, a new building for the museum's collections was completed in 2016 on the city's outskirts in Nanguan District near Jingyuetan Park.[61] Badabu is a group of buildings of the former eight Manchukuo ministries which are Ministry of Public Safety, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Economy, Ministry of Communications, Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Culture and Education, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Civil Affairs [62] that has recently become a sightseeing highlight because of their unique combined Chinese, Japanese and Manchurian architecture.

Jingyuetan National Forest Park is located to the southeast of the city, and is one of the AAAAA Tourist Attractions of China.[63] The park hosts Vasaloppet China annually.[64][65]

Economy

editChangchun achieved a gross domestic product (GDP) of RMB332.9 billion in 2010, representing a rise of 15.3 percent year on year. Primary industry output increased by 3.3 percent to RMB25.27 billion. Secondary industry output experienced an increase of 19.0 percent, reaching RMB171.99 billion, while the tertiary industry output increased 12.6 percent to RMB135.64 billion. The GDP per capita of Changchun was ¥58,691 in 2012, which equates to $9338. The GDP of Changchun in 2012 was RMB445.66 billion and increased 12.0 percent compared with 2011. The primary industry grew 4.3 percent to RMB31.71 billion. Secondary industry increased by RMB229.19 billion, which is a rise of 13.1 percent year on year. Tertiary industry of Changchun in 2012 grew 11.8 percent and increased by RMB184.76 billion.[5]

The city's leading industries are production of automobiles, agricultural product processing, biopharmaceuticals, photo electronics, construction materials, and the energy industry.[10] Changchun is the largest automobile manufacturing, research and development centre in China, producing 9 percent of the country's automobiles in 2009. Changchun is home to China's biggest vehicle producer FAW (First Automotive Works) Group, which manufactured the first Chinese truck in 1956 and car in 1958. The automaker's factories and associated housing and services occupy a substantial portion of the city's southwest end. Specific brands produced in Changchun include the Red Flag luxury brand, as well as joint ventures with Audi, Volkswagen, and Toyota. In 2012, FAW sold 2.65 million units of auto. The sales revenue of FAW amounted to RMB 408.46 billion, representing a rise of 10.8% on year.[10] As cradle of the auto industry, one of Changchun's better known nicknames is "China's Detroit".[12]

Manufacturing of transportation facilities and machinery is also among Changchun's main industries. 50 percent of China's passenger trains, and 10 percent of tractors are produced in Changchun. Changchun Railway Vehicles, one of the main branches of China CNR Corporation, has a joint venture established with Bombardier Transportation to build Movia metro cars for the Guangzhou Metro and Shanghai Metro,[66] and the Tianjin Metro.

Foreign direct investment in the city was US$3.68 billion in 2012, up 19.6% year on year.[10] In 2004 Coca-Cola set up a bottling plant in the city's ETDZ with an investment of US$20 million.[67]

Changchun hosts the yearly Changchun International Automobile Fair, Changchun Film Festival, Changchun Agricultural Fair, Education Exhibition and the Sculpture Exhibition.

CRRC manufactures most of its bullet train carriages at its factory in Changchun. In November 2016, CRCC Changchun unveiled the first bullet train carriages in the world with sleeper berths, thus extending their use for overnight passages across China. They would be capable of running in ultra low temperature environments. Nicknamed Panda, the new bullet trains are capable of running at 250 km/h, operate at −40 degrees Celsius, have Wi-Fi hubs and contain sleeper berths that fold into seats during the day.[68]

Other large companies in Changchun include:

- Yatai Group, established in 1993 and listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange in 1995. It has developed into a major conglomerate involved in a wide range of industries including property development, cement manufacturing, securities, coal mining, pharmaceuticals and trading.[69]

- Jilin Grain Group, a major processor of grains.[70][failed verification]

Development zones

editChangchun Automotive Economic Trade and Development Zone

editFounded in 1993, the Changchun Automotive Trade Center was re-established as the Changchun Automotive Economic Trade and Development Zone in 1996. The development zone is situated in the southwest of the city and is adjacent to the China First Automobile Works Group Corporation and the Changchun Film ThemeCity. It covers a total area of approximately 300,000 square metres (3,229,173 square feet). Within the development zone lies an exhibition center and five specially demarcated industrial centers. The Changchun Automobile Wholesale Center began operations in 1994 and is the largest auto-vehicle and spare parts wholesale center in China. The other centers include a resale center for used auto-vehicles, a specialized center for industrial/commercial vehicles, and a tire wholesale center.[67]

Changchun High Technology Development Zone

editThe zone is one of the first 27 state-level advanced technology development zones and is situated in the southern part of the city, covering a total area of 49 km2 (19 sq mi). There are 18 full-time universities and colleges, 39 state and provincial-level scientific research institutions, and 11 key national laboratories. The zone is mainly focusing on developing five main industries, namely bio-engineering, automobile engineering, new material fabrication, photo-electricity, and information technology.

Changchun Economic and Technological Development Zone

editEstablished in April 1993, the zone enjoys all the preferential policies stipulated for economic and technological development zones of coastal open cities.[67] The total area of CETDZ is 112.72 square kilometres (43.52 square miles), of which 30 square kilometres (12 square miles) has been set aside for development and utilization.[71] It is located 5 kilometres (3 miles) from downtown Changchun, 2 km (1.2 mi) from the freight railway station and 15 km (9 mi) from the Changchun international airport. The zone is devoted to developing five leading industries: namely automotive parts and components, photoelectric information, bio-pharmaceutical, fine processing of foods, and new building materials. In particular, high-tech and high value added projects account for over 80 percent of total output. In 2006 the zone's total fixed assets investment rose to RMB38.4 billion. Among the total of 1656 enterprises registered, 179 are foreign-funded. The zone also witnessed a total industrial output of RMB 277 billion in 2007.[67]

Infrastructure

editChangchun is a very compact city, planned by the Japanese with a layout of open avenues and public squares. The city is developing its layout in a long-term bid to alleviate pressure on limited land, aid economic development, and absorb a rising population. According to a draft plan up until 2020, the downtown area will expand southwards to form a new city center around Changchun World Sculpture Park, Weixing Square and their outskirts, and the new development zone. For the north of the city, there is a new development zone called "Changchun New Area", locate near the North Lake Park.[67]

Transport

editRailways

editChangchun has two passenger rail stations, all conventional trains and some high-speed trains stop at the central Changchun railway station (simplified Chinese: 长春站; traditional Chinese: 長春站), which is connected by Beijing-Harbin Railway, Changchun-Hunchun intercity railway and several railway lines. The station has multiple daily departures to other cities in the province and northeast area, such as Jilin City, Yanji, Harbin, Shenyang, and Dalian, as well as other major cities throughout the country such as Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou.[citation needed] The new Changchun West railway station, situated in the western end of urbanized area, is the station mainly for the high-speed trains of the Harbin–Dalian high-speed railway.[72][73]

Bus and Tram

editChangchun is served by a comprehensive bus system, which having more than 250 bus route, most buses charge 1-2 yuan per ride.

Changchun is one of the few cities preserving the historic tram system in China. The tram system first opened in 1941, having 6 lines covering almost 53 km at its peak. But after several route adjustments, there is only one line left since the 2000s. A new branch line is opened in 2014, which links the new Changchun West Railway Station. The whole system is now operated under the bus system of Changchun.

Rapid Transit

editChangchun Rail Transit is a rapid transit system of Changchun, combining light rail lines and metro lines. Its first line was opened on 30 October 2002, making Changchun the fifth metropolitan city in China to open rail transit.

Till November 2018, there are 5 lines in Changchun, including Line 1, Line 2, Line 3, Line 4, and Line 8. Changchun railway covers about 100.17 kilometers.

Till September 2019, there are 4 lines of Changchun Rail Transit under construction, including Line 6 and Line 9, as well as Line 2 West Extension and Line 3 East Extension. By 2025, the Changchun rail transit line network will consist of 10 lines with a total length of 341.62 kilometers.[citation needed]

In September 2019, the average daily passenger volume of Changchun Rail Transit reached 680,400 person, and the maximum daily passenger volume of its line network was 830,500 person on 13 November 2019. The total estimated passenger volume in 2019 is about 168 million person.[citation needed]

Road network

editChangchun is linked to the national highway network through the Beijing – Harbin Expressway (G1), the Ulanhot – Changchun – Jilin – Hunchun Expressway (G12), the Changchun – Shenzhen Expressway (G25), the Changchun – Changbaishan Expressway (S1) and the busiest section in the province, the Changchun–Jilin North Highway. This section connects the two biggest cities in Jilin and is the trunk line for the social and economic communication of the two cities.[67]

Private automobiles are becoming very common on the city's congested streets. Bicycles are relatively rare compared to other northeastern Chinese cities, but mopeds, as well as pedal are relatively common.[citation needed]

Air

editChangchun Longjia International Airport is located 31.2 kilometres (19.4 miles) north-east of Changchun urban area. The airport's construction began in 1998, and was intended to replace the older Changchun Dafangshen Airport, which was a joint-use airport built in 1941. The airport opened for passenger service on 27 August 2005.[74] The operation of the airport is shared by both Changchun and nearby Jilin City.[75]

Education

editUniversities and colleges

editChangchun is ranked one of the top 30 cities in the world by scientific research as tracked by the Nature Index according to the Nature Index 2024 Science Cities.[13] The city has 27 regular institutions of full-time tertiary education with a total enrollment of approximate 160,000 students. Jilin University and Northeast Normal University are two key universities in China.[45] Jilin University is also one of the largest universities in China, with more than 60,000 students.

- Changchun Normal University

- Changchun University

- Changchun University of Science and Technology

- Changchun University of Chinese Medicine[76]

- Jilin College of the Arts

- Jilin Huaqiao Foreign Languages Institute, a private college offering bachelor study programs in foreign languages, international trade management and didactics[77]

- Jilin University

- Jilin University of Finance and Economics

- Jilin Agricultural University

- Northeast Normal University

- Jilin Engineering Normal University

- Changchun Institute of Technology[78]

Middle schools

edit- High School Attached to Northeast Normal University

- Affiliated Middle School to Jilin University

- No.72 Middle School of Changchun

- Second experimental school of Jilin Province

- No.11 High School of Changchun

- Changchun No.6 middle school

- Changchun Foreign Languages School

Primary and secondary schools

editInternational schools include:

Sports and stadiums

editAs a major Chinese city, Changchun is home to many professional sports teams:

- Jilin Northeast Tigers (Basketball), is a competitive team which has long been one of the major clubs fighting in China top-level league, CBA.

- Changchun Yatai, who have played home soccer matches at the Development Area Stadium since 2009.[80] In 2007 they won the Chinese Super League.[81]

There are two major multi-purpose stadiums in Changchun, including Changchun City Stadium and Development Area Stadium.

- Changchun Wuhuan Gymnasium, the main venue of the 2007 Asian Winter Games.

- It has an indoor speed skating arena, Jilin Provincial Speed Skating Rink,[82] as one of five in China.[83]

Jinlin Tseng Tou are a professional ice hockey team based in the city, and compete in the Russian-based Supreme Hockey League.[84] They are one of two Chinese-based teams to enter the league during the 2017–18 season, the other being based in Harbin.[citation needed]

Film

editNotable people

edit- Ei-ichi Negishi (根岸 英一), 2010 Nobel Prize winner in chemistry, was born in Changchun

- Liu Xiaobo (刘晓波), 2010 Nobel Peace Prize winner, was born in Changchun

- Cheng Yonghua (born 1954), diplomat who served as Ambassador to Japan from 2010 to 2019.

Twin towns and sister cities

edit- Nuuk, Sermersooq, Greenland

- Sendai, Miyagi, Japan

- Ulsan, Yeongnam, South Korea

- Flint, Michigan, United States

- Little Rock, Arkansas, United States

- Windsor, Ontario, Canada

- Ulan-Ude, Buryatia, Russia

- Minsk, Belarus

- Chongjin, North Hamgyong, North Korea

- Birmingham, West Midlands, United Kingdom

- Wolfsburg, Lower Saxony, Germany

- Žilina, Slovakia

- Novi Sad, Vojvodina, Serbia

- Masterton, Wellington Region, New Zealand

See also

edit- List of twin towns and sister cities in China

- Changchun smog

- Changchun Confucius Temple

- Category:People from Changchun

Notes

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ a b "Geographic Location". Changchun Municipal Government. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2008.

- ^ Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, ed. (2019). China Urban Construction Statistical Yearbook 2017. Beijing: China Statistics Press. p. 50. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ a b "China: Jílín (Prefectures, Cities, Districts and Counties) - Population Statistics, Charts and Map". Archived from the original on 23 September 2014.

- ^ 吉林省统计局、国家统计局吉林调查总队 (September 2016). 《吉林统计年鉴-2016》. 中国统计出版社. ISBN 978-7-5037-7899-5. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ a b 2010年长春市国民经济和社会发展统计公报 [Statistics Communique on National Economy and Social Development of Changchun, 2010] (in Chinese). 5 June 2011. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ "Definition of CHANGCHUN". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ "Changchun". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021.

- ^ "Illuminating China's Provinces, Municipalities and Autonomous Regions-Jilin". PRC Central Government Official Website. 2001. Archived from the original on 19 June 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ 中央机构编制委员会印发《关于副省级市若干问题的意见》的通知. 中编发[1995]5号. 豆丁网 (in Chinese). 19 February 1995. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Changchun (Jilin) City Information". HKTDC Research. Archived from the original on 8 January 2015.

- ^ "Changchun Business Guide – Economic Overview". echinacities.com. Retrieved 26 July 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Spacing: Understanding the Urban Landscape". SpacingToronto. 2008. Archived from the original on 22 July 2010. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ a b "Leading 200 science cities | | Supplements | Nature Index". www.nature.com. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ 新京特別市公署『新京市政概要』12–13頁、新京商工公会刊『新京の概況 建国十周年記念發刊』1–7頁、『満洲年鑑』昭和20年(康徳12年)版 389–390頁、他を参照。[full citation needed]

- ^ "History". Changchun Municipal Government. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ a b Zhiting, Li (28 June 2005). "Changchun II- Le chemin de fer de Changchun". cctv.com-Francais (in French). Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ a b "Provisional Convention ... concerning the junction of the Japanese and Russian Railways in Manchuria" – 13 June 1907. Endowment for International Peace (2009). Manchuria: Treaties and Agreements. BiblioBazaar, LLC. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-113-11167-8. Archived from the original on 19 May 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ Luis Jackson, Industrial Commissioner of the Erie Railroad. "Rambles in Japan and China". In Railway and Locomotive Engineering Archived 14 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, vol. 26 (March 1913), pp. 91–92

- ^ Nishiura, Hiroshi (9 May 2006). Epidemiology of a primary pneumonic plague in Kantoshu, Manchuria, from 1910 to 1911: statistical analysis of individual records collected by the Japanese Empire (PDF). Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the International Epidemiological Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ Jing-tao, Wang. "Analysis of the Rat Plague of Northeast China and the Sanitary and Antiepidemic Condition of Yanbian in the Early 20th Century" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 30 October 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ Gamsa, M. (1 February 2006). "The Epidemic of Pneumonic Plague in Manchuria 1910–1911". Past & Present (190): 147–183. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtj001. S2CID 161797143.

- ^ Akira Koshizawa, Manchukuo Capital Planning (Jiangsu: Social Sciences Academic Press,2011), 26–97.

- ^ Yishi Liu, "A Pictorial History of Changchun, 1898–1962," Cross Current 5, (2012): 191–217.

- ^ a b c Akira Koshizawa, Manchukuo Capital Planning (Jiangsu: Social Sciences Academic Press,2011), 26–97

- ^ "YESTERDAY AND TO-DAY". Victoria University of Wellington. 1 April 1932. p. 30. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ 大同元年4月1日国務院佈告第1号「満洲国国都ヲ長春ニ奠ム」(大同元年3月10日)

- ^ 大同元年4月1日国務院佈告第2号「国都長春ヲ新京ト命名ス」(大同元年3月14日)

- ^ 「特別市指定ニ関スル件廃止ニ関スル件」(康徳4年6月27日勅令第142号)

- ^ a b 国務院国都建設局『國都大新京』(日譯)16頁[full citation needed]

- ^ 長春浄月潭. j.people.com.cn (in Japanese). 人民網日本株式会社事業案内. 26 March 2010. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ 新京特別市公署『新京市政概要』6頁[full citation needed]

- ^ 首都警察廳正式成立ノ件(大同元年10月18日民政部訓令第286号)

- ^ 後に「首都警察廳官制中改正ノ件」(康徳4年9月30日勅令第282号)により、新京特別市のみを管轄とした。

- ^ 新京特別市公署『新京市政概要』7頁[full citation needed]

- ^ 『満洲年鑑』昭和20年(康徳12年)版、1944年、389頁[full citation needed]

- ^ 『満洲年鑑』等では「新京市政公署」の記述も見られる。

- ^ 侵华日军使用细菌武器述略 (in Chinese). 人民日报社. 16 June 2005. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ^ Harris, Sheldon H. Factories of Death: Japanese Biological Warfare, 1932–45 , and the American Cover-Up. London: Routledge, 1994.

- ^ LTC David M. Glantz, "August Storm: The Soviet 1945 Strategic Offensive in Manchuria" Archived 23 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Leavenworth Papers No. 7, Combat Studies Institute, February 1983, Fort Leavenworth Kansas.

- ^ Dikötter, Frank. (2013). The Tragedy of Liberation: A History of the Chinese Revolution, 1945-1957 (1 ed.). London: Bloomsbury Press. pp. 3–8. ISBN 978-1-62040-347-1.

- ^ China Is Wordless on Traumas of Communists' Rise Archived 8 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, 1 October 2009

- ^ Pomfret, John (2 October 2009). Red Army Starved 150,000 Chinese Civilians. Archived from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Chang, Jung; Halliday, Jon. 2006. Mao: The Unknown Story. London: Vintage Books. p383.

- ^ Jacobs, Andrew (2 October 2009). "China Is Wordless on Traumas of Communists' Rise". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 November 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ a b "Society". Changchun Municipal Government. Archived from the original on 20 August 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ a b FAW Group Steps up Global Expansion FAW Official Site, 27 March 2007 Archived 19 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b About FAW > Key Events FAW Official Site Archived 4 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Mao's Red Flag Returning To Drive China Leaders From Audi: Cars". bloomberg.com. Bloomberg LP. 27 February 2012. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ "Asian Winter Games open in northeastern city Changchun". CCTV.com. 29 January 2007. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ a b c "Experience Template" CMA台站气候标准值(1991-2020) (in Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ a b 长春城市介绍. Weather China (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ 中国气象数据网 – WeatherBk Data (in Chinese (China)). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ 中国地面国际交换站气候标准值月值数据集(1971-2000年). China Meteorological Administration. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Changchun, China – Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast". Weather Atlas. Yu Media Group. Archived from the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ a b "Communiqué of the National Bureau of Statistics of People's Republic of China on Major Figures of the 2010 Population Census" (in Chinese). National Bureau of Statistics of China. 20 July 2011. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ "Exploring the Ethnic Groups of China | Cusef Blog". China-United States Exchange Foundation. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ a b 走进长春 长春特色 (in Chinese (China)). Changchun People's Government. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ 长春原来有这么多的寺庙楼堂 值得收藏拜访. Sohu News (in Chinese (China)). Retrieved 21 November 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Li, Fusheng (27 August 2012). "Culture blossoms in Jilin". China Daily. Archived from the original on 4 October 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ 吉林省博物院 (in Chinese (China)). Jilin Province Department of Culture and Tourism. 16 November 2005. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ Wang, Zhen (29 September 2016). "Seven highlights from the new Jilin provincial museum". China Daily. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ Tucker, D. (1999). Building "Our manchukuo" : Japanese city planning, architecture, and nation-building in occupied Northeast China, 1931-1945.

- ^ "Jingyuetan National Forest Park, Changchun". govt.chinadaily.com.cn. China Daily. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ "The Vasaloppet China Changchun Jingyuetan International Ski Festival 2023 Kicks Off Grandly". en.changchun.gov.cn. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ "Vasaloppet ski festival plays it cool to attract crowds". govt.chinadaily.com.cn. China Daily. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ "Bombardier to supply 246 Movia cars for Shanghai Line 12". Railway Gazette International. 18 December 2009. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f "China Briefing Business Reports" (PDF). Asia Briefing. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ "China develops bullet train with fold-up beds". China Daily. Xinhua. 14 November 2016. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ^ "Jilin Yatai Group Company Limited". Archived from the original on 4 October 2011.

- ^ "Changchun". China Economy @ China Perspective. 2014. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ "Changchun Economic and Technology Development Zone | China Industrial Space". Rightsite.asia. RightSite Website Technology. Archived from the original on 25 October 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ "World's fastest railway in frigid regions starts operation". English.news.cn. 1 December 2012. Archived from the original on 4 December 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ "Harbin-Dalian high-speed rail went into operation on December 1". Website of Jilin Province Government. 27 November 2012. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ 长春龙嘉国际机场本月27日零时将正式启用 (in Simplified Chinese). 25 August 2005. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ "Information about Changchun Airports". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ "Changchun University of Chinese Medicine Homepage". Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ Jilin Huaqiao Foreign Languages Institute Archived 27 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Changchun Institute of Technology Homepage". Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ "长春圣约翰公学". www.stjohnschangchun.com. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ 亚泰主场迁至经开体育场. chinajilin.com.cn (in Chinese (China)). 30 March 2009. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ "China League Tables 2007". Rsssf.com. 18 April 2008. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ "Rink card of: Jilin Provincial Speed Skating Rink Changchun". Archived from the original on 21 March 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ "image". Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- ^ "Высшая хоккейная лига - Команды". Archived from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

Sources

editExternal links

edit- Changchun travel guide from Wikivoyage

- Changchun Government website

- Changchun Foreign Affairs Information Portal