Claremont is the only city in Sullivan County, New Hampshire, United States.[3] The population was 12,949 at the 2020 census.[4] Claremont is a core city of the Lebanon–Claremont micropolitan area, a bi-state, four-county region in the upper Connecticut River valley.

Claremont, New Hampshire | |

|---|---|

| |

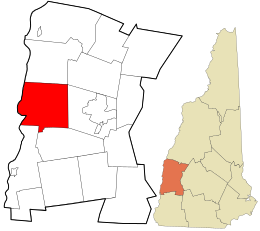

Location in Sullivan County and the state of New Hampshire | |

| Coordinates: 43°22′20″N 72°20′15″W / 43.37222°N 72.33750°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New Hampshire |

| County | Sullivan |

| Settled | 1762[1] |

| Incorporated | 1764 (town), 1947 (city) |

| Villages |

|

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Dale Girard |

| • Assistant Mayor | Debora Matteau |

| • City Council | Members

|

| • City Manager | Yoshi Manale |

| Area | |

• Total | 44.05 sq mi (114.09 km2) |

| • Land | 43.15 sq mi (111.77 km2) |

| • Water | 0.90 sq mi (2.32 km2) 2.04% |

| Elevation | 551 ft (168 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 12,949 |

| • Density | 300.07/sq mi (115.86/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 03743 |

| Area code | 603 |

| FIPS code | 33-12900 |

| GNIS feature ID | 866173[3] |

| Website | www |

History

editPre-colonial native populations

editThe Upper Connecticut River Valley was home to the Pennacook and Western Abenaki (Sokoki) peoples, later merging with members of other Algonquin tribes displaced by the wars and famines that accompanied the European settling of the region.[5] The Hunter Archeological Site, located near the bridge connecting Claremont with Ascutney, Vermont, is a significant prehistoric Native American site that includes seven levels of occupational evidence, including evidence of at least three longhouses. The oldest dates recorded from evidence gathered during excavations in 1967 were to 1300 CE.[6]

Colonial settlement

editThe city was named after Claremont, the country mansion of Thomas Pelham-Holles, Earl of Clare.[7] On October 26, 1764,[8] colonial governor Benning Wentworth granted the township to Josiah Willard, Samuel Ashley and 67 others. Although first settled in 1762 by Moses Spafford and David Lynde, many of the proprietors arrived in 1767, with a large number from Farmington, Hebron and Colchester, Connecticut. The undulating surface of rich, gravelly loam made agriculture an early occupation.[9] Spafford was deeded land from Col. Samuel Ashley, who was given a charter to establish a ferry across the Connecticut River in 1784, the location of which is still known as Ashley's Ferry landing. Spafford was also the first man to marry in Claremont, and his son, Elijah, was the first white child to be born in the town.

The Union Episcopal Church in West Claremont was built in 1773, and is the oldest surviving Episcopal church building in New Hampshire and the state's oldest surviving building built exclusively for religious purposes. The parish was organized in 1771 and chartered by the New Hampshire legislature in 1794 as Union Church Parish.[10] Located across the street, Old St. Mary's Church, built in 1823 mostly in the Federal style, was the first Roman Catholic church in New Hampshire.[11] It was discontinued in 1870 in favor of the new St. Mary's Church in the Lower Village District.[12]

During the American Revolution, Claremont had a large number of Loyalists, who used a small wooded valley in West Claremont called the "Tory Hole" to hide from the Patriots.[13][14] In 1777, when the New Hampshire Grants declared their own sovereignty as the Vermont Republic, Claremont was one of sixteen New Hampshire towns inclined to join them, and made multiple attempts to do so.[13]

Industry

editClaremont's first millwright was Col. Benjamin Tyler, who arrived in the area from Farmington, Connecticut, in the spring of 1767.[13] Tyler built mills using stone quarried from his land on nearby Mount Ascutney, and built Claremont's first mill on the Sugar River on the site of the Coy Paper Mill. Tyler also invented the wry-fly water wheel, which was the subject of the Supreme Court case Tyler v. Tuel. His grandson John Tyler evolved the technology to create the Tyler Water Wheel and the Tyler Turbine. John Tyler's grandson was Benjamin Tyler Henry, inventor of the Henry Repeating rifle, manufactured in neighboring Windsor, Vermont, and used in the Civil War.[15]

The water power harnessed from the Sugar River brought the town prosperity during the Industrial Revolution. Large brick factories were built along the stream, including the Sunapee Mills, Monadnock Mills, Claremont Machine Works, Home Mills, Sanford & Rossiter, and Claremont Manufacturing Company. Principal products were cotton and woolen textiles, lathes and planers, and paper.[9] Although like other New England mill towns, much industry moved away or closed in the 20th century, the city's former prosperity is evident in some fine Victorian architecture, including the 1897 city hall and opera house.

In 1874, businesses in Claremont included Monadnock Mills, manufacturing cotton cloths from one to three yards wide, Marseilles quilts, union flannels, and lumber, and employing 125 males and 225 females; Home Mill (A. Briggs & Co.) producing cotton cloth and employing 8 males and 20 females; Sullivan Machine Co., manufacturing Steam Dimond Drill Machinery for quarrying rock, turbine water wheels, cloth measuring machines, and doing general machine and mill work, employing 56 males; Sugar River Paper Mill Co., manufacturing printing paper and employing 30 males and 20 females; Claremont Manufacturing Co., manufacturing paper and books, and doing stereotyping and book and job printing, employing 34 males and 34 females; Russell Jarvis, manufacturing hanging paper and employing 7 males and 2 females; John S. Farrington, manufacturing straw wrapping paper and employing 5 males and 1 female; Sullivan Mills (George L. Balcom), manufacturing black doeskins and employing 20 males and 18 females; Charles H. Eastman, in the leather business and employing 4 males; Sugar River Mill Co., manufacturing flour, feed, and doing custom grinding, and employing 8 males; three saw mills employing a part of the year, 10 males; Blood & Woodcock, in the business of monuments and grave stones and employing 8 males; and Houghton, Bucknam & Co., in the business of sashes, doors and blinds, employing 8 males.[8]

The Monadnock Mills Co. and Sullivan Mills Co. were responsible for the two most prominent collections of manufacturing structures in the Lower Village District. Monadnock Mills' textile operations began with its founding in 1842, and lasted through 1932, shuttering operations following the decline of the textile industry in New England during the 1920s.[16] By the 1920s, Sullivan Mills Co. had become New Hampshire's largest machining company, as well as Claremont's largest employer. Sullivan's Machinery division merged with Joy Mining Machinery in 1946, becoming Joy Manufacturing Co. Its founder, inventor Joseph Francis Joy, stayed on as general manager of the facility,[17] which remained the dominant employer in Claremont through the 1970s, when manufacturing technology had advanced sufficiently to hamper sales and productivity. Parts of the campus suffered fires in 1979 and 1981,[18] and the branch was closed in 1983 and sold in 1984.[16]

-

Statue and memorial to Civil War dead

-

32-pounder (6.5") Dahlgren naval guns

Educational history

editIn the 1850s, the city of Claremont approached the state legislature asking permission to build a public high school. At the time, public high schools did not exist in New Hampshire. The state agreed, and decided to offer permission to every town in the state so that every town could establish public high schools. Claremont native and hotelier Paran Stevens then made an offer to fund 50% of the $20,000 cost of development, resulting in Stevens High School.[15]

In March 1989, the Claremont School Board voted to initiate a lawsuit against the State of New Hampshire, claiming that the state's primary reliance upon local property taxes for funding education resulted in inequitable educational opportunities among children around the state and a violation of their constitutional rights. Following a lawsuit and a series of landmark decisions, the New Hampshire Supreme Court agreed. Known as the "Claremont Decision", the suit continues to drive the statewide debate on equitable funding for education, and Claremont continues to play a primary role in this legal challenge.[19]

Namesakes

editThe cities of Claremont, California, Claremont, Minnesota, and Claremont Township, Minnesota, were named for Claremont, New Hampshire.[20]

Geography

editThe city is in western Sullivan County and is bordered to the west by the Connecticut River, the boundary between New Hampshire and Vermont. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 44.1 square miles (114.1 km2), of which 43.2 square miles (111.8 km2) are land and 0.89 square miles (2.3 km2) are water, comprising 2.04% of the town.[21] The Sugar River flows from east to west through the center of Claremont, descending 150 feet (46 m) in elevation through the downtown, and empties into the Connecticut. The highest point in the city is the summit of Green Mountain, at 2,018 feet (615 m) above sea level in the northeastern part of the city. Claremont lies fully within the Connecticut River watershed.[22]

Adjacent municipalities

edit- Cornish (north)

- Newport (east)

- Unity (southeast)

- Charlestown (southwest)

- Weathersfield, Vermont (west)

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 1,435 | — | |

| 1800 | 1,889 | 31.6% | |

| 1810 | 2,094 | 10.9% | |

| 1820 | 1,702 | −18.7% | |

| 1830 | 2,526 | 48.4% | |

| 1840 | 3,217 | 27.4% | |

| 1850 | 3,606 | 12.1% | |

| 1860 | 4,026 | 11.6% | |

| 1870 | 4,053 | 0.7% | |

| 1880 | 4,704 | 16.1% | |

| 1890 | 5,565 | 18.3% | |

| 1900 | 6,498 | 16.8% | |

| 1910 | 7,529 | 15.9% | |

| 1920 | 9,524 | 26.5% | |

| 1930 | 12,377 | 30.0% | |

| 1940 | 12,144 | −1.9% | |

| 1950 | 12,811 | 5.5% | |

| 1960 | 13,563 | 5.9% | |

| 1970 | 14,221 | 4.9% | |

| 1980 | 14,557 | 2.4% | |

| 1990 | 13,902 | −4.5% | |

| 2000 | 13,151 | −5.4% | |

| 2010 | 13,355 | 1.6% | |

| 2020 | 12,949 | −3.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[23] | |||

As of the census of 2010, there were 13,355 people, 5,697 households, and 3,461 families residing in the city. The population density was 309.9 inhabitants per square mile (119.7/km2). There were 6,293 housing units at an average density of 146.0 per square mile (56.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 95.9% White, 0.6% African American, 0.3% Native American, 0.9% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.4% some other race, and 1.8% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.3% of the population.[24]

There were 5,697 households, out of which 28.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 42.1% were headed by married couples living together, 13.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.2% were non-families. 30.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.8% were someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.31, and the average family size was 2.83.[24]

In the city, the population was spread out, with 22.0% under the age of 18, 8.0% from 18 to 24, 26.0% from 25 to 44, 28.7% from 45 to 64, and 15.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40.6 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 93.1 males.[24]

For the period 2009–2013, the estimated median annual income for a household in the city was $42,236, and the median income for a family was $51,259. Male full-time workers had a median income of $43,261 versus $35,369 for females. The per capita income for the city was $22,773. About 13.3% of families and 15.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 22.2% of those under age 18 and 5.3% of those aged 65 or over.[25]

Arts and culture

editA commercial area centered on Washington Street is Claremont's primary commercial district. An Italian Renaissance-styled City Hall building, which houses the historic Claremont Opera House, was built in 1897 and designed by architect Charles A. Rich.[26] City Hall faces Broad Street Park, a rotary-style town square. This square connects Washington Street, Broad Street, and Main Street, which branch into different portions of the city. Broad Street Park contains war monuments to World War I, World War II, Korea and Vietnam, and Freedom Garden Memorial dedicated to the victims and families of September 11. Included are two Civil War cannon and the centrally-located Soldier's Monument, designed by Martin Milmore and dating to 1890.[27] The park is also home to a historic bandstand, originally built in a Victorian style in 1890[27] and redesigned in 1922 in a Classical Revival style,[28] which primarily serves as performance space for the Claremont American Band, a community band dating to about 1880.[29] Parallel to Broad Street lies Pleasant Street, home to a downtown business district, which was the city's primary commercial zone until the development of the Washington Street district.

A number of mill buildings dot the Lower Village District in the city's center, along the Sugar River, and several attempts have been made at historic preservation of some of them.

To the north end of the town lies the Valley Regional Hospital, an out-patient resource of the popular Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center of Lebanon.

On the southern artery out of Claremont, Route 12, stood Highland View, the summer home of Claremont native William Henry Harrison Moody (1842–1925), who made his fortunes as a businessman and shoe manufacturer in the Boston area, but kept a residence in his hometown until his death.[30] The large William H. H. Moody estate was known for its horses and its five large barns (the last of which burned in 2004 from a lightning strike[31]), which once hosted several hundred imported horses on over 500 acres (2.0 km2). Its Victorian farmhouse stands at the top of Arch Road. In March 1916, a 175-acre (71 ha) portion of the estate was donated by Moody to the city of Claremont for a city park, the entrance of which is on Maple Avenue; facilities include tennis. A lone access road leads through a coniferous forest to the top of a hill, maintained as a large field by the city, with a large, open-air stone structure suitable for picnics. The park has several miles of interconnected walking trailways; several of these trails terminate at the Boston and Maine Railroad.[32][33]

In 2021, The Ko'asek (Co'wasuck)Traditional Band of the Sovereign Abenaki Nation, a group claiming descent of the original indigenous population in the region, acquired and was gifted several parcels of local land for use in cultural ceremonies, nature preserves and education along with growing herbs and plants.[34][35] In 2024 the group claims 554 members and now owns 26.37 acres in Claremont.[34]

Notable sites

edit- Arrowhead Recreation Area

- Claremont Historical Society & Museum[36]

- Claremont Municipal Airport

- Sugar River Rail Trail[37]

- Twin State Speedway[38]

Historic sites

edit- Claremont Opera House

- David Dexter House

- Hunter Archeological Site

- Lower Village Historic District[39]

- Monadnock Mills Historic District[40]

- Union Episcopal Church

- William Rossiter House

Education

editClaremont is part of New Hampshire's School Administrative Unit 6, or SAU 6. Stevens High School is the city's only public high school, and is located on Broad Street, just a few blocks from City Hall. Claremont Middle School, the city's only public middle school, is located just down the street to the south.

Claremont is home to three elementary schools: Maple Avenue School, Bluff Elementary and Disnard Elementary. Also located in town are the New England Classical Academy, a private, Catholic school, and the Claremont Christian Academy, a private, parochial school offering education through 12th grade.

Three elementary schools—North Street School, Way Elementary and the West Claremont Schoolhouse—were shut down, Way becoming home to several luxury apartments and North Street turned into offices.

The city's opportunities for higher education include a branch of Granite State College, River Valley Community College, and the Sugar River Valley Regional Technical Center.

Infrastructure

editTransportation

editThe only city within Sullivan County, Claremont is home to Claremont Municipal Airport. By highway, it is located 21 miles (34 km) south of Interstate 89 in Lebanon, New Hampshire, and 5 miles (8 km) east of Interstate 91 in Weathersfield, Vermont. It is served by state routes 11, 12, 12A 103, and 120. Routes 11 and 103 travel east as a concurrency to Newport, with Route 11 continuing east to New London and Franklin, while Route 103 turns southeast to Bradford and Warner. Routes 11 and 12 lead south as a concurrency to Charlestown. West from downtown, Route 12 leads into Vermont, then turns north to Windsor. Route 120 leads north from downtown through Cornish and Meriden to Lebanon. Route 12A bypasses downtown Claremont to the west, leading south to Charlestown and north to West Lebanon.

Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, provides daily service aboard its Vermonter between Washington, D.C., and St. Albans, Vermont. The closest Greyhound bus stops are in Bellows Falls and White River Junction, Vermont. Local weekday peak direction commuter bus service between Springfield, Vermont, and Hanover, New Hampshire, is operated by the Current from the Interstate 91 Exit 8 Park and Ride in Ascutney, Vermont.

-

US Post Office at 140 Broad St.

-

Central Fire Station at 100 Broad St.

Notable people

edit- Doug Berry (born 1948), football coach[41]

- Edmund Burke (1809–1882), U.S. congressman from Vermont[42]

- Derastus Clapp (1792–1881), detective[43]

- Barbara Cochran (born 1951), Olympic gold medalist ski racer[15]

- Franceway Ranna Cossitt (1790–1863), Cumberland Presbyterian minister[44]

- Caleb Ellis (1767–1816), U.S. congressman[45]

- Harriet Farley (1812–1907), writer, abolitionist[15]

- Kirk Hanefeld (born 1956), golfer[46]

- Jule Murat Hannaford (1850–1934), railway president[47]

- Benjamin Tyler Henry (1821–1898), gunsmith, manufacturer; inventor of the Henry rifle, the first reliable lever-action repeating rifle

- Jeffrey R. Howard (born 1955), judge[48]

- Jonathan Hatch Hubbard (1768–1849), U.S. congressman from Vermont[49]

- Dorothy Loudon (1925–2003), actress[15]

- Larry McElreavy (born 1946), college football coach[50]

- Jennifer Militello, poet[51]

- Thomas Mitchell (1816–1894), Iowa politician[52]

- Hosea Washington Parker (1833–1922), U.S. congressman[53]

- Orrin W. Robinson (1834–1907), politician, businessman[54]

- Kaleb Tarczewski (born 1993), basketball player[55]

- George B. Upham (1768–1848), U.S. congressman[56]

- William J. Wilgus (1865–1949), designer of New York City's Grand Central Terminal[15]

- Constance Fenimore Woolson (1840–1894), novelist, short story writer[57]

In popular culture

editWrightsville, the fictional small-town setting in New England of many Ellery Queen novels and short stories, was based on Claremont. Ellery Queen was the pen name of cousins Frederic Dannay (1905–1982) and Manfred B. Lee (1905–1971). Betty Miller, a Claremont native, had married Manfred B. Lee in 1927. According to the Queen Spaceports website, the Claremont Eagle newspaper provided front-page coverage (on July 10, 1959) of a talk Manfred Lee gave, in which he revealed that Wrightsville was indeed based on Claremont.[58][59]

Claremont was the filming location, though not the setting, of the 2006 movie Live Free or Die, co-written and co-directed by Gregg Kavet and Andy Robin and starring Aaron Stanford, Paul Schneider, Michael Rapaport, Judah Friedlander, Kevin Dunn, and Zooey Deschanel. Set in fictional Rutland, New Hampshire, it is a picaresque comedy-drama about a small-town would-be crime legend. The name of the movie derives from the motto of the Granite State.[60]

The Topstone Mill, formerly a shoe factory and now housing a restaurant,[61] was featured in season 8, episode 20 of Ghost Hunters, airing October 24, 2012, titled "Fear Factory".[62]

Claremont was featured in the fourteenth episode of the Small Town News Podcast, an improv comedy podcast that takes listeners on a fun and silly virtual trip to a small town in America each week, in which the hosts improvise scenes inspired by local newspaper stories.[63]

Gallery of historic postcards

edit-

Bird's-eye view c. 1910

-

Sugar River falls c. 1905

-

Tremont Square c. 1912

-

Hotel Claremont in 1907

-

Broad Street in 1908

-

Fiske Free Library in 1908

-

Sullivan Street c. 1910

-

Monadnock Mills in 1910

See also

edit- New Hampshire Historical Marker No. 41: First Roman Catholic Church

- New Hampshire Historical Marker No. 57: Union Church

- New Hampshire Historical Marker No. 188: Historic Handshake

References

edit- ^ "Area History". City of Claremont official website. Archived from the original on July 9, 2015. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Claremont

- ^ "Census - Geography Profile: Claremont city, New Hampshire". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ "Abenaki History". tolatsga.org. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ Starbuck, David (2006). The Archeology of New Hampshire. Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire Press. p. 89. ISBN 9781584655626.

- ^ "Profile for Claremont, New Hampshire, NH". ePodunk. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ a b Article in Statistics and Gazetteer of New-Hampshire (1875)

- ^ a b Coolidge, Austin J.; John B. Mansfield (1859). A History and Description of New England, General and Local. Boston, Massachusetts: A.J. Coolidge. pp. 445–448.

coolidge mansfield history description new england 1859.

- ^ "Union Episcopal Church (English Church)". Connecticut River Joint Commissions. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: New Hampshire". newadvent.org. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ "Old St. Mary Roman Catholic Church". Connecticut River Joint Commissions. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ a b c Granite Monthly: A New Hampshire Magazine. 1913. pp. 1–386. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ "Chapter IV. Historic Resources" (PDF). City of Claremont Master Plan. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "Historian highlights: Early contributors to Claremont". Valley News. Archived from the original on July 2, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ a b "A Walking Tour of Claremont Village Industrial District" (PDF). City of Claremont. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 20, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ "Joseph Francis Joy: Character – Inventor – Reformer" (PDF). joyglobal.com. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ "Chief Roy T. Quimby". Unity N.H. Volunteer Fire Department. Retrieved February 3, 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Claremont Coalition". claremontlawsuit.org. Archived from the original on June 7, 2007. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ Chicago and North Western Railway Company (1908). A History of the Origin of the Place Names Connected with the Chicago & North Western and Chicago, St. Paul, Minneapolis & Omaha Railways, p. 56.

- ^ "2021 U.S. Gazetteer Files – New Hampshire". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2022.

- ^ Foster, Debra H.; Batorfalvy, Tatianna N.; Medalie, Laura (1995). Water Use in New Hampshire: An Activities Guide for Teachers. U.S. Department of the Interior and U.S. Geological Survey.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (DP-1): Claremont city, New Hampshire". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ "Selected Economic Characteristics: 2009-2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates (DP03): Claremont city, New Hampshire". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ "History". Claremont Opera House. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ a b "Trail 6 – Connecticut River Heritage Trail". Connecticut River Historic Sites Database & Connecticut River Heritage Trails. Archived from the original on May 15, 2016. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ "A Secret Jewel: Claremont NH". bandstands.blogspot.com. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ McElreavy, W.L. (2012). Claremont. Arcadia Pub. (SC). p. 100. ISBN 9780738592978. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ Davis, W.T. (1897). The New England States: Their Constitutional, Judicial, Educational, Commercial, Professional and Industrial History. Vol. 1. D.H. Hurd & Co. p. 294. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ "Claremont Firefighters Association". kkg500.com. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ "Moody Park: Community Park & Trail System" (PDF). City of Claremont. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 22, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ Sanborn, Colin J. "W.H.H. Moody". Claremont Historical Society. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ a b "Ko'asek (Co'wasuck) Traditional Band of the Sovereign Abenaki Nation". Ko'asek (Co'wasuck) Traditional Band of the Sovereign Abenaki Nation. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ Kisluk, Jessica (November 19, 2023). "New Hampshire Native American tribe continuing work on cultural center, small village in Claremont". WMUR. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ Claremont Historical Society & Museum

- ^ Sugar River Rail Trail Archived 2009-06-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Twin State Speedway". Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved May 19, 2009.

- ^ Lower Village Historic District

- ^ Monadnock Mills Historic District

- ^ "Blue Bombers fire head coach Doug Berry". The Toronto Star. the star.com. November 12, 2008. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ "BURKE, Edmund, (1809 - 1882)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ Clap, Ebenezer (1876). The Clapp Memorial: Record of the Clapp Family in America: Containing Sketches of the Original Six Emigrants, and a Genealogy of Their Descendants Bearing the Name: With a Supplement and the Proceedings at Two Family Meetings. David Clapp & Son. p. 60.

- ^ Middlebury College (1917). Catalogue of Officers and Students of Middlebury College in Middlebury, Vermont: And of Others who Have Received Degrees, 1800-1915. The College. p. 26.

- ^ "ELLIS, Caleb, (1767 - 1816)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ "KIRK HANEFELD". PGA Tour Inc. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ "Who's Who in Finance Incorporated". Who's Who in Finance and Banking: A Biographical Dictionary of Contemporaries, 1920-1922. 1922. p. 298.

- ^ "Biographical Directory of Federal Judges: Howard, Jeffrey R." Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ "HUBBARD, Jonathan Hatch, (1768 - 1849)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ "Larry McElreavy". New-York Historical Society. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ "Jennifer Militello, Poet, Goffstown". New Hampshire State Council of the Arts. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ "State Representative". Iowa Legislature. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ "PARKER, Hosea Washington, (1833–1922)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ "Robinson, O to R". A Database of American History: Index to Politicians. The Political Graveyard. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ "35 - Kaleb Tarczewski". NBAdraft,Net. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ "UPHAM, George Baxter, (1768 - 1848)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ Moore, Rayburn S. (1932). Constance Fenimore Woolson. Ardent Media. p. 18.

- ^ "Wrightsville". queen.spaceports.com. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- ^ "Claremont, the Real Wrightsville". queen.spaceports.com. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- ^ "Live Free or Die". IMDB. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ "Ghost-hunters-recap-haunted-shoe-factory-filled-with-ghostly-footsteps". realitytvmagazine.sheknows.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ ""Ghost Hunters" Fear Factory (TV Episode 2012) - IMDb". imdb.com. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ "Small Town News".