Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (6 October 1887 – 27 August 1965), known as Le Corbusier (UK: /lə kɔːrˈbjuːzi.eɪ/ lə kor-BEW-zee-ay,[2] US: /lə ˌkɔːrbuːzˈjeɪ, -buːsˈjeɪ/ lə KOR-booz-YAY, -booss-YAY,[3][4] French: [lə kɔʁbyzje]),[5] was a Swiss-French architect, designer, painter, urban planner and writer, who was one of the pioneers of what is now regarded as modern architecture. He was born in Switzerland to French speaking Swiss parents, and acquired French nationality by naturalization on 19 September 1930.[6] His career spanned five decades, in which he designed buildings in Europe, Japan, India, as well as North and South America.[7] He considered that "the roots of modern architecture are to be found in Viollet-le-Duc".[8]

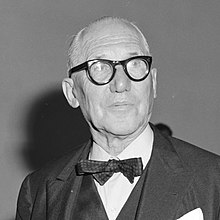

Le Corbusier | |

|---|---|

Le Corbusier in 1964 | |

| Born | Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris[1] 6 October 1887 La Chaux-de-Fonds, Neuchâtel, Switzerland |

| Died | 27 August 1965 (aged 77) Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, Alpes-Maritimes, France |

| Nationality | Swiss, French |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards |

|

| Buildings | Villa Savoye, Poissy Villa La Roche, Paris Unité d'habitation, Marseille Notre Dame du Haut, Ronchamp Buildings in Chandigarh, India |

| Projects | Ville Radieuse |

| Signature | |

Dedicated to providing better living conditions for the residents of crowded cities, Le Corbusier was influential in urban planning, and was a founding member of the Congrès International d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM). Le Corbusier prepared the master plan for the city of Chandigarh in India, and contributed specific designs for several buildings there, especially the government buildings.

On 17 July 2016, seventeen projects by Le Corbusier in seven countries were inscribed in the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites as The Architectural Work of Le Corbusier, an Outstanding Contribution to the Modern Movement.[9]

Le Corbusier remains a controversial figure. Some of his urban planning ideas have been criticized for their indifference to pre-existing cultural sites, societal expression and equality, and his alleged ties with fascism, antisemitism, eugenics,[10] and the dictator Benito Mussolini have resulted in some continuing contention.[11][12][13][14]

Le Corbusier also designed well-known furniture such as the LC4 Chaise Lounge chair and the LC1 chair, both made of leather with metal framing.

Early life (1887–1904)

editCharles-Édouard Jeanneret was born on 6 October 1887 in La Chaux-de-Fonds, a city in the Neuchâtel canton in the Romandie region of Switzerland. His ancestors included Belgians with the surname Lecorbésier, which inspired the pseudonym Le Corbusier which he would adopt as an adult.[15] His father was an artisan who enameled boxes and watches, and his mother taught piano. His elder brother Albert was an amateur violinist.[16] He attended a kindergarten that used Fröbelian methods.[17][18][19]

Located in the Jura Mountains 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) across the border from France, La Chaux-de-Fonds was a burgeoning city at the heart of the Watch Valley. Its culture was influenced by the Loge L'Amitié, a Masonic lodge upholding moral, social, and philosophical ideas symbolized by the right angle (rectitude) and the compass (exactitude). Le Corbusier would later describe these as "my guide, my choice" and as "time-honored ideas, ingrained and deep-rooted in the intellect, like entries from a catechism."[7]

Like his contemporaries Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier lacked formal training as an architect. He was attracted to the visual arts; at the age of fifteen, he entered the municipal art school in La-Chaux-de-Fonds which taught the applied arts connected with watchmaking. Three years later he attended the higher course of decoration, founded by the painter Charles L'Eplattenier, who had studied in Budapest and Paris. Le Corbusier wrote later that L'Eplattenier had made him "a man of the woods" and taught him about painting from nature.[16] His father frequently took him into the mountains around the town. He wrote later, "we were constantly on mountaintops; we grew accustomed to a vast horizon."[20] His architecture teacher in the Art School was architect René Chapallaz, who had a large influence on Le Corbusier's earliest house designs. He reported later that it was the art teacher L'Eplattenier who made him choose architecture. "I had a horror of architecture and architects," he wrote. "...I was sixteen, I accepted the verdict and I obeyed. I moved into architecture."[21]

Travel and first houses (1905–1914)

edit-

Le Corbusier's student project, the Villa Fallet, a chalet in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland (1905)

-

The "Maison Blanche", built for Le Corbusier's parents in La Chaux-de-Fonds (1912)

-

The Villa Favre-Jacot in Le Locle, Switzerland (1912)

Le Corbusier began teaching himself by going to the library to read about architecture and philosophy, visiting museums, sketching buildings, and constructing them. In 1905, he and two other students, under the supervision of their teacher, René Chapallaz, designed and built his first house, the Villa Fallet, for the engraver Louis Fallet, a friend of his teacher Charles L'Eplattenier. Located on the forested hillside near Chaux-de-fonds, it was a large chalet with a steep roof in the local alpine style and carefully crafted coloured geometric patterns on the façade. The success of this house led to his construction of two similar houses, the Villas Jacquemet and Stotzer, in the same area.[22]

In September 1907, he made his first trip outside of Switzerland, going to Italy; then that winter travelling through Budapest to Vienna, where he stayed for four months and met Gustav Klimt and tried, without success, to meet Josef Hoffmann.[23] In Florence, he visited the Florence Charterhouse in Galluzzo, which made a lifelong impression on him. "I would have liked to live in one of what they called their cells," he wrote later. "It was the solution for a unique kind of worker's housing, or rather for a terrestrial paradise."[24] He travelled to Paris, and for fourteen months between 1908 and 1910 he worked as a draftsman in the office of the architect Auguste Perret, the pioneer of the use of reinforced concrete in residential construction and the architect of the Art Deco landmark Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. Two years later, between October 1910 and March 1911, he travelled to Germany and worked for four months in the office Peter Behrens, where Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius were also working and learning.[25]

In 1911, he travelled again with his friend August Klipstein for five months;[26] this time he journeyed to the Balkans and visited Serbia, Bulgaria, Turkey, Greece, as well as Pompeii and Rome, filling nearly 80 sketchbooks with renderings of what he saw—including many sketches of the Parthenon, whose forms he would later praise in his work Vers une architecture (1923). He spoke of what he saw during this trip in many of his books, and it was the subject of his last book, Le Voyage d'Orient.[25]

In 1912, he began his most ambitious project: a new house for his parents, also located on the forested hillside near La-Chaux-de-Fonds. The Jeanneret-Perret house was larger than the others, and in a more innovative style; the horizontal planes contrasted dramatically with the steep alpine slopes, and the white walls and lack of decoration were in sharp contrast with the other buildings on the hillside. The interior spaces were organized around the four pillars of the salon in the centre, foretelling the open interiors he would create in his later buildings. The project was more expensive to build than he imagined; his parents were forced to move from the house within ten years and relocate to a more modest house. However, it led to a commission to build an even more imposing villa in the nearby village of Le Locle for a wealthy watch manufacturer, Georges Favre-Jacot. Le Corbusier designed the new house in less than a month. The building was carefully designed to fit its hillside site, and the interior plan was spacious and designed around a courtyard for maximum light, a significant departure from the traditional house.[27]

Dom-ino House and Schwob House (1914–1918)

editDuring World War I, Le Corbusier taught at his old school in La-Chaux-de-Fonds. He concentrated on theoretical architectural studies using modern techniques.[28] In December 1914, along with the engineer Max Dubois, he began a serious study of the use of reinforced concrete as a building material. He had first discovered concrete working in the office of Auguste Perret, the pioneer of reinforced concrete architecture in Paris, but now wanted to use it in new ways.

"Reinforced concrete provided me with incredible resources," he wrote later, "and variety, and a passionate plasticity in which by themselves my structures will be the rhythm of a palace, and a Pompieen tranquillity."[29] This led him to his plan for the Dom-Ino House (1914–15). This model proposed an open floor plan consisting of three concrete slabs supported by six thin reinforced concrete columns, with a stairway providing access to each level on one side of the floor plan.[30] The system was originally designed to provide large numbers of temporary residences after World War I, producing only slabs, columns and stairways, and residents could build exterior walls with the materials around the site. He described it in his patent application as "a juxtiposable system of construction according to an infinite number of combinations of plans. This would permit, he wrote, "the construction of the dividing walls at any point on the façade or the interior."

Under this system, the structure of the house did not have to appear on the outside but could be hidden behind a glass wall, and the interior could be arranged in any way the architect liked.[31] After it was patented, Le Corbusier designed several houses according to the system, which was all white concrete boxes. Although some of these were never built, they illustrated his basic architectural ideas which would dominate his works throughout the 1920s. He refined the idea in his 1927 book on the Five Points of a New Architecture. This design, which called for the disassociation of the structure from the walls, and the freedom of plans and façades, became the foundation for most of his architecture over the next ten years.[32]

In August 1916, Le Corbusier received his largest commission ever, to construct a villa for the Swiss watchmaker Anatole Schwob, for whom he had already completed several small remodelling projects. He was given a large budget and the freedom to design not only the house but also to create the interior decoration and choose the furniture. Following the precepts of Auguste Perret, he built the structure out of reinforced concrete and filled the gaps with brick. The centre of the house is a large concrete box with two semicolumn structures on both sides, which reflects his ideas of pure geometrical forms. A large open hall with a chandelier occupied the centre of the building. "You can see," he wrote to Auguste Perret in July 1916, "that Auguste Perret left more in me than Peter Behrens."[33]

Le Corbusier's grand ambitions collided with the ideas and budget of his client and led to bitter conflicts. Schwob went to court and denied Le Corbusier access to the site, or the right to claim to be the architect. Le Corbusier responded, "Whether you like it or not, my presence is inscribed in every corner of your house." Le Corbusier took great pride in the house and reproduced pictures in several of his books.[34]

Painting, Cubism, Purism and L'Esprit Nouveau (1918–1922)

editLe Corbusier moved to Paris definitively in 1917 and began his architectural practise with his cousin, Pierre Jeanneret (1896–1967), a partnership that would last until the 1950s, with an interruption in the World War II years.[35]

In 1918, Le Corbusier met the Cubist painter Amédée Ozenfant, in whom he recognised a kindred spirit. Ozenfant encouraged him to paint, and the two began a period of collaboration. Rejecting Cubism as irrational and "romantic", the pair jointly published their manifesto, Après le cubisme and established a new artistic movement, Purism. Ozenfant and Le Corbusier began writing for a new journal, L'Esprit Nouveau, and promoted with energy and imagination his ideas of architecture.

In the first issue of the journal, in 1920, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret adopted Le Corbusier (an altered form of his maternal grandfather's name, Lecorbésier) as a pseudonym, reflecting his belief that anyone could reinvent themselves.[36][37] Adopting a single name to identify oneself was in vogue by artists in many fields during that era, especially in Paris.

Between 1918 and 1922, Le Corbusier did not build anything, concentrating his efforts on Purist theory and painting. In 1922, he and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret opened a studio in Paris at 35 rue de Sèvres.[28] They set up an architectural practice together. From 1927 to 1937 they worked together with Charlotte Perriand at the Le Corbusier-Pierre Jeanneret studio.[38] In 1929 the trio prepared the "House fittings" section for the Decorative Artists Exhibition and asked for a group stand, renewing and widening the 1928 avant-garde group idea. This was refused by the Decorative Artists Committee. They resigned and founded the Union of Modern Artists ("Union des artistes modernes": UAM).

His theoretical studies soon advanced into several different single-family house models. Among these, was the Maison "Citrohan." The project's name was a reference to the French Citroën automaker, for the modern industrial methods and materials, Le Corbusier advocated using in the house's construction as well as how he intended the homes would be consumed, similar to other commercial products, like the automobile.[39]

As part of the Maison Citrohan model, Le Corbusier proposed a three-floor structure, with a double-height living room, bedrooms on the second floor, and a kitchen on the third floor. The roof would be occupied by a sun terrace. On the exterior, Le Corbusier installed a stairway to provide second-floor access from the ground level. Here, as in other projects from this period, he also designed the façades to include large uninterrupted banks of windows. The house used a rectangular plan, with exterior walls that were not filled by windows but left as white, stuccoed spaces. Le Corbusier and Jeanneret left the interior aesthetically spare, with any movable furniture made of tubular metal frames. Light fixtures usually comprised single, bare bulbs. Interior walls also were left white.

Toward an Architecture (1920–1923)

editIn 1922 and 1923, Le Corbusier devoted himself to advocating his new concepts of architecture and urban planning in a series of polemical articles published in L'Esprit Nouveau. At the Paris Salon d'Automne in 1922, he presented his plan for the Ville Contemporaine, a model city for three million people, whose residents would live and work in a group of identical sixty-story tall apartment buildings surrounded by lower zig-zag apartment blocks and a large park. In 1923, he collected his essays from L'Esprit Nouveau published his first and most influential book, Towards an Architecture. He presented his ideas for the future of architecture in a series of maxims, declarations, and exhortations, pronouncing that "a grand epoch has just begun. There exists a new spirit. There already exist a crowd of works in the new spirit, they are found especially in industrial production. Architecture is suffocating in its current uses. "Styles" are a lie. Style is a unity of principles which animates all the work of a period and which result in a characteristic spirit...Our epoch determines each day its style..-Our eyes, unfortunately, don't know how to see it yet," and his most famous maxim, "A house is a machine to live in." Most of the many photographs and drawings in the book came from outside the world of traditional architecture; the cover showed the promenade deck of an ocean liner, while others showed racing cars, aeroplanes, factories, and the huge concrete and steel arches of zeppelin hangars.[40]

L'Esprit Nouveau Pavilion (1925)

editAn important early work of Le Corbusier was the Esprit Nouveau Pavilion, built for the 1925 Paris International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, the event which later gave Art Deco its name. Le Corbusier built the pavilion in collaboration with Amédée Ozenfant and with his cousin Pierre Jeanneret. Le Corbusier and Ozenfant had broken with Cubism and formed the Purism movement in 1918 and in 1920 founded their journal L'Esprit Nouveau. In his new journal, Le Corbusier vividly denounced the decorative arts: "Decorative Art, as opposed to the machine phenomenon, is the final twitch of the old manual modes, a dying thing." To illustrate his ideas, he and Ozenfant decided to create a small pavilion at the Exposition, representing his idea of the future urban housing unit. A house, he wrote, "is a cell within the body of a city. The cell is made up of the vital elements which are the mechanics of a house...Decorative art is antistandardizational. Our pavilion will contain only standard things created by industry in factories and mass-produced, objects truly of the style of today...my pavilion will therefore be a cell extracted from a huge apartment building."[41]

Le Corbusier and his collaborators were given a plot of land located behind the Grand Palais in the centre of the Exposition. The plot was forested, and exhibitors could not cut down trees, so Le Corbusier built his pavilion with a tree in the centre, emerging through a hole in the roof. The building was a stark white box with an interior terrace and square glass windows. The interior was decorated with a few cubist paintings and a few pieces of mass-produced commercially available furniture, entirely different from the expensive one-of-a-kind pieces in the other pavilions. The chief organizers of the Exposition were furious and built a fence to partially hide the pavilion. Le Corbusier had to appeal to the Ministry of Fine Arts, which ordered that fence be taken down.[41]

Besides the furniture, the pavilion exhibited a model of his 'Plan Voisin', his provocative plan for rebuilding a large part of the centre of Paris. He proposed to bulldoze a large area north of the Seine and replace the narrow streets, monuments and houses with giant sixty-story cruciform towers placed within an orthogonal street grid and park-like green space. His scheme was met with criticism and scorn from French politicians and industrialists, although they were favourable to the ideas of Taylorism and Fordism underlying his designs. The plan was never seriously considered, but it provoked discussion concerning how to deal with the overcrowded poor working-class neighbourhoods of Paris, and it later saw the partial realization in the housing developments built in the Paris suburbs in the 1950s and 1960s.

The Pavilion was ridiculed by many critics, but Le Corbusier, undaunted, wrote: "Right now one thing is sure. 1925 marks the decisive turning point in the quarrel between the old and new. After 1925, the antique-lovers will have virtually ended their lives . . . Progress is achieved through experimentation; the decision will be awarded on the field of battle of the 'new'."[42]

The Decorative Art of Today (1925)

editIn 1925, Le Corbusier combined a series of articles about decorative art from "L'Esprit Nouveau" into a book, L'art décoratif d'aujourd'hui (The Decorative Art of Today).[43][44] The book was a spirited attack on the very idea of decorative art. His basic premise, repeated throughout the book, was: "Modern decorative art has no decoration."[45] He attacked with enthusiasm the styles presented at the 1925 Exposition of Decorative Arts: "The desire to decorate everything about one is a false spirit and an abominable small perversion....The religion of beautiful materials is in its final death agony...The almost hysterical onrush in recent years toward this quasi-orgy of decor is only the last spasm of a death already predictable."[46] He cited the 1912 book of the Austrian architect Adolf Loos "Ornament and crime", and quoted Loos's dictum, "The more a people are cultivated, the more decor disappears." He attacked the deco revival of classical styles, what he called "Louis Philippe and Louis XVI moderne"; he condemned the "symphony of color" at the Exposition, and called it "the triumph of assemblers of colors and materials. They were swaggering in colors... They were making stews out of fine cuisine." He condemned the exotic styles presented at the Exposition based on the art of China, Japan, India and Persia. "It takes energy today to affirm our western styles." He criticized the "precious and useless objects that accumulated on the shelves" in the new style. He attacked the "rustling silks, the marbles which twist and turn, the vermilion whiplashes, the silver blades of Byzantium and the Orient...Let's be done with it!"[47]

"Why call bottles, chairs, baskets and objects decorative?" Le Corbusier asked. "They are useful tools....The decor is not necessary. Art is necessary." He declared that in the future the decorative arts industry would produce only "objects which are perfectly useful, convenient, and have a true luxury which pleases our spirit by their elegance and the purity of their execution and the efficiency of their services. This rational perfection and precise determinate creates the link sufficient to recognize a style." He described the future of decoration in these terms: "The idea is to go work in the superb office of a modern factory, rectangular and well-lit, painted in white Ripolin (a major French paint manufacturer); where healthy activity and laborious optimism reign." He concluded by repeating "Modern decoration has no decoration".[47]

The book became a manifesto for those who opposed the more traditional styles of the decorative arts; In the 1930s, as Le Corbusier predicted, the modernized versions of Louis Philippe and Louis XVI furniture and the brightly coloured wallpapers of stylized roses were replaced by a more sober, more streamlined style. Gradually the modernism and functionality proposed by Le Corbusier overtook the more ornamental style. The shorthand titles that Le Corbusier used in the book, 1925 Expo: Arts Deco were adapted in 1966 by the art historian Bevis Hillier for a catalogue of an exhibition on the style, and in 1968 in the title of a book, Art Deco of the 20s and 30s. And thereafter the term "Art Deco" was commonly used as the name of the style.[48]

Five Points of Architecture to Villa Savoye (1923–1931)

edit-

The Villa La Roche-Jeanneret (now Fondation Le Corbusier) in Paris (1923)

-

Corbusier Haus (right) and Citrohan Haus in Weissenhof, Stuttgart, Germany (1927)

-

The Villa Savoye in Poissy (1928–1931)

The notoriety that Le Corbusier achieved from his writings and the Pavilion at the 1925 Exposition led to commissions to build a dozen residences in Paris and the Paris region in his "purist style." These included the Maison La Roche/Albert Jeanneret (1923–1925), which now houses the Fondation Le Corbusier; the Maison Guiette in Antwerp, Belgium (1926); a residence for Jacques Lipchitz; the Maison Cook, and the Maison Planeix. In 1927, he was invited by the German Werkbund to build three houses in the model city of Weissenhof near Stuttgart, based on the Citroen House and other theoretical models he had published. He described this project in detail in one of his best-known essays, the Five Points of Architecture.[49]

The following year he began the Villa Savoye (1928–1931), which became one of the most famous of Le Corbusier's works, and an icon of modernist architecture. Located in Poissy, in a landscape surrounded by trees and a large lawn, the house is an elegant white box poised on rows of slender pylons, surrounded by a horizontal band of windows which fill the structure with light. The service areas (parking, rooms for servants and laundry room) are located under the house. Visitors enter a vestibule from which a gentle ramp leads to the house itself. The bedrooms and salons of the house are distributed around a suspended garden; the rooms look both out at the landscape and into the garden, which provides additional light and air. Another ramp leads up to the roof, and a stairway leads down to the cellar under the pillars.

Villa Savoye succinctly summed up the five points of architecture that he had elucidated in L'Esprit Nouveau and the book Vers une architecture, which he had been developing throughout the 1920s. First, Le Corbusier lifted the bulk of the structure off the ground, supporting it by pilotis, reinforced concrete stilts. These pilotis, in providing the structural support for the house, allowed him to elucidate his next two points: a free façade, meaning non-supporting walls that could be designed as the architect wished, and an open floor plan, meaning that the floor space was free to be configured into rooms without concern for supporting walls. The second floor of the Villa Savoye includes long strips of ribbon windows that allow unencumbered views of the large surrounding garden, which constitute the fourth point of his system. The fifth point was the roof garden to compensate for the green area consumed by the building and replace it on the roof. A ramp rising from ground level to the third-floor roof terrace allows for a promenade architecturale through the structure. The white tubular railing recalls the industrial "ocean-liner" aesthetic that Le Corbusier much admired.

Le Corbusier was quite rhapsodic when describing the house in Précisions in 1930: "the plan is pure, exactly made for the needs of the house. It has its correct place in the rustic landscape of Poissy. It is Poetry and lyricism, supported by technique."[50] The house had its problems; the roof persistently leaked, due to construction faults; but it became a landmark of modern architecture and one of the best-known works of Le Corbusier.[50]

League of Nations Competition and Pessac Housing Project (1926–1930)

editThanks to his passionate articles in L'Esprit Nouveau, his participation in the 1925 Decorative Arts Exposition and the conferences he gave on the new spirit of architecture, Le Corbusier had become well known in the architectural world, though he had only built residences for wealthy clients. In 1926, he entered the competition for the construction of a headquarters for the League of Nations in Geneva with a plan for an innovative lakeside complex of modernist white concrete office buildings and meeting halls. There were 337 projects in competition. It appeared that the Corbusier's project was the first choice of the architectural jury, but after much behind-the-scenes manoeuvring, the jury declared it was unable to pick a single winner, and the project was given instead to the top five architects, who were all neoclassicists. Le Corbusier was not discouraged; he presented his plans to the public in articles and lectures to show the opportunity that the League of Nations had missed.[51]

The Cité Frugès

editIn 1926, Le Corbusier received the opportunity he had been looking for; he was commissioned by a Bordeaux industrialist, Henry Frugès, a fervent admirer of his ideas on urban planning, to build a complex of worker housing, the Cité Frugès, at Pessac, a suburb of Bordeaux. Le Corbusier described Pessac as "A little like a Balzac novel", a chance to create a whole community for living and working. The Fruges quarter became his first laboratory for residential housing; a series of rectangular blocks composed of modular housing units located in a garden setting. Like the unit displayed at the 1925 Exposition, each housing unit had its own small terrace. The earlier villas he constructed all had white exterior walls, but for Pessac, at the request of his clients, he added colour; panels of brown, yellow and jade green, coordinated by Le Corbusier. Originally planned to have some two hundred units, it finally contained about fifty to seventy housing units, in eight buildings. Pessac became the model on a small scale for his later and much larger Cité Radieuse projects.[52]

Founding of CIAM (1928) and Athens Charter

editIn 1928, Le Corbusier took a major step toward establishing modernist architecture as the dominant European style. Le Corbusier had met with many of the leading German and Austrian modernists during the competition for the League of Nations in 1927. In the same year, the German Werkbund organized an architectural exposition at the Weissenhof Estate Stuttgart. Seventeen leading modernist architects in Europe were invited to design twenty-one houses; Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe played a major part. In 1927 Le Corbusier, Pierre Chareau and others proposed the foundation of an international conference to establish the basis for a common style. The first meeting of the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne or International Congresses of Modern Architects (CIAM), was held in a château on Lake Leman in Switzerland 26–28 June 1928. Those attending included Le Corbusier, Robert Mallet-Stevens, Auguste Perret, Pierre Chareau and Tony Garnier from France; Victor Bourgeois from Belgium; Walter Gropius, Erich Mendelsohn, Ernst May and Mies van der Rohe from Germany; Josef Frank from Austria; Mart Stam and Gerrit Rietveld from the Netherlands, and Adolf Loos from Czechoslovakia. A delegation of Soviet architects was invited to attend, but they were unable to obtain visas. Later members included Josep Lluís Sert of Spain and Alvar Aalto of Finland. No one attended from the United States. A second meeting was organized in 1930 in Brussels by Victor Bourgeois on the topic "Rational methods for groups of habitations". A third meeting, on "The functional city", was scheduled for Moscow in 1932, but was cancelled at the last minute. Instead, the delegates held their meeting on a cruise ship travelling between Marseille and Athens. On board, they together drafted a text on how modern cities should be organized. The text, called The Athens Charter, after considerable editing by Le Corbusier and others, was finally published in 1943 and became an influential text for city planners in the 1950s and 1960s. The group met once more in Paris in 1937 to discuss public housing and was scheduled to meet in the United States in 1939, but the meeting was cancelled because of the war. The legacy of the CIAM was a roughly common style and doctrine which helped define modern architecture in Europe and the United States after World War II.[53]

Projects (1928–1963)

editMoscow projects (1928–1934)

editLe Corbusier saw the new society founded in the Soviet Union after the Russian Revolution as a promising laboratory for his architectural ideas. He met the Russian architect Konstantin Melnikov during the 1925 Decorative Arts Exposition in Paris, and admired the construction of Melnikov's constructivist USSR pavilion, the only truly modernist building in the Exposition other than his own Esprit Nouveau pavilion. At Melnikov's invitation, he travelled to Moscow, where he found that his writings had been published in Russian; he gave lectures and interviews and between 1928 and 1932 he constructed an office building for the Tsentrosoyuz, the headquarters of Soviet trade unions.

In 1932, he was invited to take part in an international competition for the new Palace of the Soviets in Moscow, which was to be built on the site of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, demolished on Stalin's orders. Le Corbusier contributed a highly original plan, a low-level complex of circular and rectangular buildings and a rainbow-like arch from which the roof of the main meeting hall was suspended. To Le Corbusier's distress, his plan was rejected by Stalin in favour of a plan for a massive neoclassical tower, the highest in Europe, crowned with a statue of Vladimir Lenin. The Palace was never built; construction was stopped by World War II, a swimming pool took its place, and after the collapse of the USSR the cathedral was rebuilt on its original site.[54]

Cité Universitaire, Immeuble Clarté and Cité de Refuge (1928–1933)

editBetween 1928 and 1934, as Le Corbusier's reputation grew, he received commissions to construct a wide variety of buildings. In 1928 he received a commission from the Soviet government to construct the headquarters of the Tsentrosoyuz, or central office of trade unions, a large office building whose glass walls alternated with plaques of stone. He built the Villa de Madrot in Le Pradet (1929–1931); and an apartment in Paris for Charles de Bestigui at the top of an existing building on the Champs-Élysées 1929–1932, (later demolished). In 1929–1930 he constructed a floating homeless shelter for the Salvation Army on the left bank of the Seine at the Pont d'Austerlitz. Between 1929 and 1933, he built a larger and more ambitious project for the Salvation Army, the Cité de Refuge, on rue Cantagrel in the 13th arrondissement of Paris. He also constructed the Swiss Pavilion in the Cité Universitaire in Paris with 46 units of student housing, (1929–33). He designed furniture to go with the building; the main salon was decorated with a montage of black-and-white photographs of nature. In 1948, he replaced this with a colourful mural he painted himself. In Geneva, he built a glass-walled apartment building with 45 units, the Immeuble Clarté. Between 1931 and 1945 he built an apartment building with fifteen units, including an apartment and studio for himself on the 6th and 7th floors, at 24 rue Nungesser-et-Coli in the 16th arrondissement in Paris. overlooking the Bois de Boulogne.[55] His apartment and studio are owned today by the Fondation Le Corbusier and can be visited.

Ville Contemporaine, Plan Voisin and Cité Radieuse (1922–1939)

editAs the global Great Depression enveloped Europe, Le Corbusier devoted more and more time to his ideas for urban design and planned cities. He believed that his new, modern architectural forms would provide an organizational solution that would raise the quality of life for the working classes. In 1922 he had presented his model of the Ville Contemporaine, a city of three million inhabitants, at the Salon d'Automne in Paris. His plan featured tall office towers surrounded by lower residential blocks in a park setting. He reported that "analysis leads to such dimensions, to such a new scale, and to such the creation of an urban organism so different from those that exist, that it that the mind can hardly imagine it."[56] The Ville Contemporaine, presenting an imaginary city in an imaginary location, did not attract the attention that Le Corbusier wanted. For his next proposal, the Plan Voisin (1925), he took a much more provocative approach; he proposed to demolish a large part of central Paris and replace it with a group of sixty-story cruciform office towers surrounded by parkland. This idea shocked most viewers, as it was certainly intended to do. The plan included a multi-level transportation hub that included depots for buses and trains, as well as highway intersections, and an airport. Le Corbusier had the fanciful notion that commercial airliners would land between the huge skyscrapers. He segregated pedestrian circulation paths from the roadways and created an elaborate road network. Groups of lower-rise zigzag apartment blocks, set back from the street, were interspersed among the office towers. Le Corbusier wrote: "The centre of Paris, currently threatened with death, threatened by exodus, is, in reality, a diamond mine...To abandon the centre of Paris to its fate is to desert in face of the enemy." [57]

As no doubt Le Corbusier expected, no one hurried to implement the Plan Voisin, but he continued working on variations of the idea and recruiting followers. In 1929, he travelled to Brazil where he gave conferences on his architectural ideas. He returned with drawings of his vision for Rio de Janeiro; he sketched serpentine multi-story apartment buildings on pylons, like inhabited highways, winding through Rio de Janeiro.

In 1931, he developed a visionary plan for another city Algiers, then part of France. This plan, like his Rio Janeiro plan, called for the construction of an elevated viaduct of concrete, carrying residential units, which would run from one end of the city to the other. This plan, unlike his early Plan Voisin, was more conservative, because it did not call for the destruction of the old city of Algiers; the residential housing would be over the top of the old city. This plan, like his Paris plans, provoked discussion but never came close to realization.

In 1935, Le Corbusier made his first visit to the United States. He was asked by American journalists what he thought about New York City skyscrapers; he responded, characteristically, that he found them "much too small".[58] He wrote a book describing his experiences in the States, Quand Les cathédrales étaient blanches, Voyage au pays des timides (When Cathedrals were White; voyage to the land of the timid) whose title expressed his view of the lack of boldness in American architecture.[59]

He wrote a great deal but built very little in the late 1930s. The titles of his books expressed the combined urgency and optimism of his messages: Cannons? Munitions? No thank you, Lodging please! (1938) and The lyricism of modern times and urbanism (1939).

In 1928, the French Minister of Labour, Louis Loucheur, won the passage of French law on public housing, calling for the construction of 260,000 new housing units within five years. Le Corbusier immediately began to design a new type of modular housing unit, which he called the Maison Loucheur, which would be suitable for the project. These units were forty-five square metres (480 square feet) in size, made with metal frames, and were designed to be mass-produced and then transported to the site, where they would be inserted into frameworks of steel and stone; The government insisted on stone walls to win the support of local building contractors. The standardisation of apartment buildings was the essence of what Le Corbusier termed the Ville Radieuse or "radiant city", in a new book published in 1935. The Radiant City was similar to his earlier Contemporary City and Plan Voisin, with the difference that residences would be assigned by family size, rather than by income and social position. In his 1935 book, he developed his ideas for a new kind of city, where the principal functions; heavy industry, manufacturing, habitation and commerce, would be separated into their neighbourhoods, carefully planned and designed. However, before any units could be built, World War II intervened.

World War II and Reconstruction; Unité d'Habitation in Marseille (1939–1952)

edit-

The modular design of the apartments inserted into the building

-

Internal "street" within the Unité d'Habitation, Marseille (1947–1952)

-

Salon and Terrace of an original unit of the Unité d'Habitation, now at the Cité de l'Architecture et du Patrimoine in Paris (1952)

During the War and the German occupation of France, Le Corbusier did his best to promote his architectural projects. He moved to Vichy for a time, where the collaborationist government of Marshal Philippe Petain was located, offering his services for architectural projects, including his plan for the reconstruction of Algiers, but they were rejected. He continued writing, completing Sur les Quatres routes (On the Four Routes) in 1941. After 1942 Le Corbusier left Vichy for Paris.[60] He became for a time a technical adviser at Alexis Carrel's eugenics foundation but resigned on 20 April 1944.[61] In 1943 he founded a new association of modern architects and builders, the Ascoral, the Assembly of Constructors for a renewal of architecture, but there were no projects to build.[62]

When the war ended Le Corbusier was nearly sixty years old and he had not had a single project realized for ten years. He tried, without success, to obtain commissions for several of the first large reconstruction projects, but his proposals for the reconstruction of the town of Saint-Dié and for La Rochelle were rejected. Still, he persisted and finally found a willing partner in Raoul Dautry, the new Minister of Reconstruction and Town Planning. Dautry agreed to fund one of his projects, a "Unité habitation de grandeur conforme", or housing units of standard size, with the first one to be built in Marseille, which had been heavily damaged during the war.[63]

This was his first public commission and was a breakthrough for Le Corbusier. He gave the building the name of his pre-war theoretical project, the Cité Radieuse, and followed the principles that he had studied before the war, proposing a giant reinforced-concrete framework into which modular apartments would fit like bottles into a bottle rack. Like the Villa Savoye, the structure was poised on concrete pylons though, because of the shortage of steel to reinforce the concrete, the pylons were more massive than usual. The building contained 337 duplex apartment modules to house a total of 1,600 people. Each module was three storeys high and contained two apartments, combined so each had two levels (see diagram above). The modules ran from one side of the building to the other and each apartment had a small terrace at each end. They were ingeniously fitted together like pieces of a Chinese puzzle, with a corridor slotted through the space between the two apartments in each module. Residents had a choice of twenty-three different configurations for the units. Le Corbusier designed furniture, carpets and lamps to go with the building, all purely functional; the only decoration was a choice of interior colours. The only mildly decorative features of the building were the ventilator shafts on the roof, which Le Corbusier made to look like the smokestacks of an ocean liner, a functional form that he admired.

The building was designed not just to be a residence but to offer all the services needed for living. On every third floor, between the modules, there was a wide corridor, like an interior street, which ran the length of the building. This served as a sort of commercial street, with shops, eating places, a nursery school and recreational facilities. A running track and small stage for theatre performances were located on the roof. The building itself was surrounded by trees and a small park.

Le Corbusier wrote later that the Unité d'Habitation concept was inspired by the visit he had made to the Florence Charterhouse at Galluzzo in Italy, in 1907 and 1910 during his early travels. He wanted to recreate, he wrote, an ideal place "for meditation and contemplation". He also learned from the monastery, he wrote, that "standardization led to perfection", and that "all of his life a man labours under this impulse: to make the home the temple of the family". [64]

The Unité d'Habitation marked a turning point in the career of Le Corbusier; in 1952, he was made a Commander of the Légion d'Honneur in a ceremony held on the roof of his new building. He had progressed from being an outsider and critic of the architectural establishment to its centre, as the most prominent French architect.[65]

Postwar projects, United Nations headquarters (1947–1952)

editLe Corbusier made another almost identical Unité d'Habitation in Rezé-les-Nantes in the Loire-Atlantique Department between 1948 and 1952, and three more over the following years, in Berlin, Briey-en-Forêt and Firminy; and he designed a factory for the company of Claude and Duval, in Saint-Dié in the Vosges. In the post-Second World War decades, Le Corbusier's fame moved beyond architectural and planning circles as he became one of the leading intellectual figures of the time.[66]

In early 1947 Le Corbusier submitted a design for the headquarters of the United Nations, which was to be built beside the East River in New York. Instead of competition, the design was to be selected by a Board of Design Consultants composed of leading international architects nominated by member governments, including Le Corbusier, Oscar Niemeyer of Brazil, Howard Robertson from Britain, Nikolai Bassov of the Soviet Union, and five others from around the world. The committee was under the direction of the American architect Wallace K. Harrison, who was also the architect for the Rockefeller family, which had donated the site for the building.

Le Corbusier had submitted his plan for the Secretariat, called Plan 23 of the 58 submitted. In Le Corbusier's plan offices, council chambers and General Assembly Hall were in a single block in the centre of the site. He lobbied hard for his project, and asked the younger Brazilian architect, Niemeyer, to support and assist him with his plan. Niemeyer, to help Le Corbusier, refused to submit his design and did not attend the meetings until the Director, Harrison, insisted. Niemeyer then submitted his plan, Plan 32, with the office building and councils and General Assembly in separate buildings. After much discussion, the Committee chose Niemeyer's plan but suggested that he collaborate with Le Corbusier on the final project. Le Corbusier urged Niemeyer to put the General Assembly Hall in the centre of the site, though this would eliminate Niemeyer's plan to have a large plaza in the centre. Niemeyer agreed with Le Corbusier's suggestion, and the headquarters was built, with minor modifications, according to their joint plan.[67]

Religious architecture (1950–63)

edit-

The chapel of Notre-Dame-du-Haut in Ronchamp (1950–1955)

-

The convent of Sainte Marie de La Tourette near Lyon (1953–1960)

-

Church of Saint-Pierre, Firminy (1960–2006)

Le Corbusier was an avowed atheist, but he also had a strong belief in the ability of architecture to create a sacred and spiritual environment. In the postwar years, he designed two important religious buildings; the chapel of Notre-Dame-du-Haut at Ronchamp (1950–1955); and the Convent of Sainte Marie de La Tourette (1953–1960). Le Corbusier wrote later that he was greatly aided in his religious architecture by a Dominican father, Marie-Alain Couturier, who had founded a movement and review of modern religious art.

Le Corbusier first visited the remote mountain site of Ronchamp in May 1950, saw the ruins of the old chapel, and drew sketches of possible forms. He wrote afterwards: "In building this chapel, I wanted to create a place of silence, of peace, of prayer, of interior joy. The feeling of the sacred animated our effort. Some things are sacred, others aren't, whether they're religious or not."[68]

The second major religious project undertaken by Le Corbusier was the Convent of Sainte Marie de La Tourette in L'Arbresle in the Rhone Department (1953–1960). Once again it was Father Couturier who engaged Le Corbusier in the project. He invited Le Corbusier to visit the starkly simple and imposing 12th–13th century Le Thoronet Abbey in Provence, and also used his memories of his youthful visit to the Erna Charterhouse in Florence. This project involved not only a chapel, but a library, refectory, rooms for meetings and reflection, and dormitories for the nuns. For the living space he used the same Modulor concept for measuring the ideal living space that he had used in the Unité d'Habitation in Marseille; height under the ceiling of 2.26 metres (7 feet 5 inches); and width 1.83 metres (6 feet 0 inches).[69]

Le Corbusier used raw concrete to construct the convent, which is placed on the side of a hill. The three blocks of dormitories are U, closed by the chapel, with a courtyard in the centre. The Convent has a flat roof and is placed on sculpted concrete pillars. Each of the residential cells has a small loggia with a concrete sunscreen looking out at the countryside. The centrepiece of the convent is the chapel, a plain box of concrete, which he called his "Box of miracles." Unlike the highly finished façade of the Unité d'Habitation, the façade of the chapel is raw, unfinished concrete. He described the building in a letter to Albert Camus in 1957: "I'm taken with the idea of a "box of miracles"....as the name indicates, it is a rectangular box made of concrete. It doesn't have any of the traditional theatrical tricks, but the possibility, as its name suggests, to make miracles."[70] The interior of the chapel is extremely simple, only benches in a plain, unfinished concrete box, with light coming through a single square in the roof and six small bands on the sides. The Crypt beneath has intense blue, red and yellow walls, and illumination by sunlight channelled from above. The monastery has other unusual features, including floor to ceiling panels of glass in the meeting rooms, window panels that fragmented the view into pieces, and a system of concrete and metal tubes like gun barrels which aimed sunlight through coloured prisms and projected it onto the walls of the sacristy and to the secondary altars of the crypt on the level below. These were whimsically termed the ""machine guns" of the sacristy and the "light cannons" of the crypt.[71]

In 1960, Le Corbusier began a third religious building, the Church of Saint Pierre in the new town of Firminy-Vert, where he had built a Unité d'Habitation and a cultural and sports centre. While he made the original design, construction did not begin until five years after his death, and work continued under different architects until it was completed in 2006. The most spectacular feature of the church is the sloping concrete tower that covers the entire interior, similar to that in the Assembly Building in his complex at Chandigarh. Windows high in the tower illuminates the interior. Le Corbusier originally proposed that tiny windows also project the form of a constellation on the walls. Later architects designed the church to project the constellation Orion.[72]

Chandigarh (1951–1956)

edit-

The High Court of Justice, Chandigarh (1951–1956)

-

Secretariat Building, Chandigarh (1952–1958)

-

Palace of Assembly (Chandigarh) (1952–1961)

Le Corbusier's largest and most ambitious project was the design of Chandigarh, the capital city of the Punjab and Haryana States of India, created after India received independence in 1947. Le Corbusier was contacted in 1950 by Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, and invited to propose a project. An American architect, Albert Mayer, had made a plan in 1947 for a city of 150,000 inhabitants, but the Indian government wanted a grander and more monumental city. Corbusier worked on the plan with two British specialists in urban design and tropical climate architecture, Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, and with his cousin, Pierre Jeanneret, who moved to India and supervised the construction until his death.

Le Corbusier, as always, was rhapsodic about his project; "It will be a city of trees," he wrote, "of flowers and water, of houses as simple as those at the time of Homer, and of a few splendid edifices of the highest level of modernism, where the rules of mathematics will reign."[73] His plan called for residential, commercial and industrial areas, along with parks and transportation infrastructure. In the middle was the capitol, a complex of four major government buildings; the Palace of the National Assembly, the High Court of Justice; the Palace of Secretariat of Ministers, and the Palace of the Governor. For financial and political reasons, the Palace of the Governor was dropped well into the construction of the city, throwing the final project somewhat off-balance.[74] From the beginning, Le Corbusier worked, as he reported, "Like a forced labourer." He dismissed the earlier American plan as "Faux-Moderne" and overly filled with parking spaces and roads. He intended to present what he had learned in forty years of urban study, and also to show the French government the opportunities they had missed in not choosing him to rebuild French cities after the War.[74] His design made use of many of his favourite ideas: an architectural promenade, incorporating the local landscape and the sunlight and shadows into the design; the use of the Modulor to give a correct human scale to each element somewhat based on the proportions of the human body;[75] and his favourite symbol, the open hand ("The hand is open to give and to receive"). He placed a monumental open hand statue in a prominent place in the design.[74]

Le Corbusier's design called for the use of raw concrete, whose surface was not smoothed or polished and which showed the marks of the forms in which it dried. Pierre Jeanneret wrote to his cousin that he was in a continual battle with the construction workers, who could not resist the urge to smooth and finish the raw concrete, particularly when important visitors were coming to the site. At one point one thousand workers were employed on the site of the High Court of Justice. Le Corbusier wrote to his mother, "It is an architectural symphony which surpasses all my hopes, which flashes and develops under the light in a way which is unimaginable and unforgettable. From far, from up close, it provokes astonishment; all made with raw concrete and a cement cannon. Adorable, and grandiose. In all the centuries no one has seen that."[76]

The High Court of Justice, begun in 1951, was finished in 1956. The building was radical in its design; a parallelogram topped with an inverted parasol. Along the walls were high concrete grills 1.5 metres (4 feet 11 inches) thick which served as sunshades. The entry featured a monumental ramp and columns that allowed the air to circulate. The pillars were originally white limestone, but in the 1960s they were repainted in bright colours, which better resisted the weather.[74]

The Secretariat, the largest building that housed the government offices, was constructed between 1952 and 1958. It is an enormous block 250 metres (820 feet) long and eight levels high, served by a ramp which extends from the ground to the top level. The ramp was designed to be partly sculptural and partly practical. Since there were no modern building cranes at the time of construction, the ramp was the only way to get materials to the top of the construction site. The Secretariat had two features which were borrowed from his design for the Unité d'Habitation in Marseille: concrete grill sunscreens over the windows and a roof terrace.[74]

The most important building of the capitol complex was the Palace of Assembly (1952–61), which faced the High Court at the other end of a five hundred meter esplanade with a large reflecting pool in the front. This building features a central courtyard, over which is the main meeting hall for the Assembly. On the roof on the rear of the building is a signature feature of Le Corbusier, a large tower, similar in form to the smokestack of a ship or the ventilation tower of a heating plant. Le Corbusier added touches of colour and texture with an immense tapestry in the meeting hall and a large gateway decorated with enamel. He wrote of this building, "A Palace magnificent in its effect, from the new art of raw concrete. It is magnificent and terrible; terrible meaning that there is nothing cold about it to the eyes."[77]

Later life and work (1955–1965)

edit-

The National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo (1954–1959)

-

Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts in Cambridge, Massachusetts (1960–1963)

-

The Centre Le Corbusier in Zürich (1962–1967)

The 1950s and 1960s were a difficult period for Le Corbusier's personal life: his wife Yvonne died in 1957 and his mother, to whom he was closely attached, died in 1960. He remained active in a wide variety of fields: in 1955 he published Poéme de l'angle droit, a portfolio of lithographs, published in the same collection as the book Jazz by Henri Matisse. In 1958 he collaborated with the composer Edgar Varèse on a work called Le Poème électronique, a show of sound and light, for the Philips Pavilion at the International Exposition in Brussels. In 1960 he published a new book, L'Atelier de la recherché patiente The workshop of patient research), simultaneously published in four languages. He received growing recognition for his pioneering work in modernist architecture: in 1959 a successful international campaign was launched to have his Villa Savoye, threatened with demolition, declared a historic monument; it was the first time that a work by a living architect had received this distinction. In 1962, in the same year as the dedication of the Palace of the Assembly in Chandigarh, the first retrospective exhibit on his work was held at the National Museum of Modern Art in Paris. In 1964, in a ceremony held in his atelier on rue de Sèvres, he was awarded the Grand Cross of the Légion d'honneur by Culture Minister André Malraux.[78]

His later architectural work was extremely varied and often based on designs of earlier projects. In 1952–1958 he designed a series of tiny holiday cabins, 2.26 by 2.26 by 2.6 metres (7.4 by 7.4 by 8.5 feet) in size, for a site next to the Mediterranean at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. He built a similar cabin for himself but the rest of the project was not realized until after his death. From 1953–to 1957 he designed the Maison du Brésil, a residential building for Brazilian students for the Cité Universitaire in Paris. Between 1954 and 1959 he built the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo.[79] His other projects included a cultural centre and stadium for the town of Firminy, where he had built his first housing project (1955–1958), and a stadium in Baghdad, Iraq (much altered since its construction). He also constructed three new Unités d'Habitation apartment blocks on the model of the original in Marseille, the first in Berlin (1956–1958), the second in Briey-en-Forêt in the Meurthe-et-Moselle Department and the third (1959–1967) in Firminy. From 1960–to 1963 he built his only building in the United States, the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[78] Jørn Utzon, the architect of the Sydney Opera House, commissioned Le Corbusier to create furnishings for the nascent opera house. Le Corbusier designed a tapestry, Les Dés Sont Jetés, which was completed in 1960.[80]

Le Corbusier died of a heart attack at age 77 in 1965 after swimming on the French Riviera.[81] At the time of his death several projects were on the drawing board: the church of Saint-Pierre in Firminy, finally completed in modified form in 2006, a Palace of Congresses for Strasbourg (1962–65) and a hospital in Venice (1961–1965), which were never built. Le Corbusier designed an art gallery[82] beside the lake in Zürich for gallery owner Heidi Weber in 1962–1967. Now called the Centre Le Corbusier, it is one of his last finished works.[83]

Estate

editThe Fondation Le Corbusier (FLC) functions as his official estate.[84] The US copyright representative for the Fondation Le Corbusier is the Artists Rights Society.[85]

Ideas

editThe Five Points of a Modern Architecture

editLe Corbusier defined the principles of his new architecture in Les cinq points de l'architecture moderne, published in 1927, and co-authored by his cousin, Pierre Jeanneret. They summarized the lessons he had learned in the previous years, which he put literally into concrete form in his villas constructed in the late 1920s, most dramatically in the Villa Savoye (1928–1931).

The five points are:

- The Pilotis, or pylon. The building is raised on reinforced concrete pylons, which allows for free circulation on the ground level, and eliminates dark and damp parts of the house.

- The Roof Terrace. The sloping roof is replaced by a flat roof; the roof can be used as a garden, for promenades, for sports or a swimming pool.

- The Free Plan. Load-bearing walls are replaced by steel or reinforced concrete columns, so the interior can be freely designed, and interior walls can be put anywhere, or left out entirely. The structure of the building is not visible from the outside.

- The Ribbon Window. Since the walls do not support the house, the windows can run the entire length of the house, so all rooms can get equal light.

- The Free Façade. Since the building is supported by columns in the interior, the façade can be much lighter and more open or made entirely of glass. There is no need for lintels or other structures around the windows.

"Architectural Promenade"

editThe "Architectural Promenade" was another idea dear to Le Corbusier, which he particularly put into play in his design of the Villa Savoye. In 1928, in Une Maison, un Palais, he described it: "Arab architecture gives us a precious lesson: it is best appreciated in walking, on foot. It is in walking, in going from one place to another, that you see develop the features of the architecture. In this house (Villa Savoye) you find a veritable architectural promenade, offering constantly varying aspects, unexpected, sometimes astonishing." The promenade at Villa Savoye, Le Corbusier wrote, both in the interior of the house and on the roof terrace, often erased the traditional difference between the inside and outside.[87]

Ville Radieuse and Urbanism

editIn the 1930s, Le Corbusier expanded and reformulated his ideas on urbanism, eventually publishing them in La Ville radieuse (The Radiant City) in 1935. Perhaps the most significant difference between the Contemporary City and the Radiant City is that the latter abandoned the class-based stratification of the former; housing was now assigned according to family size, not economic position.[88] Some have read dark overtones into The Radiant City: from the "astonishingly beautiful assemblage of buildings" that was Stockholm, for example, Le Corbusier saw only "frightening chaos and saddening monotony." He dreamed of "cleaning and purging" the city, bringing "a calm and powerful architecture"—referring to steel, plate glass, and reinforced concrete. Although Le Corbusier's designs for Stockholm did not succeed, later architects took his ideas and partly "destroyed" the city with them.[89]

Le Corbusier hoped that politically minded industrialists in France would lead the way with their efficient Taylorist and Fordist strategies adopted from American industrial models to reorganize society. As Norma Evenson has put it, "the proposed city appeared to some an audacious and compelling vision of a brave new world, and to others, a frigid megalomaniacally scaled negation of the familiar urban ambient."[90]

Le Corbusier "His ideas—his urban planning and his architecture—are viewed separately," Perelman noted, "whereas they are the same thing."[91]

In La Ville radieuse, he conceived an essentially apolitical society, in which the bureaucracy of economic administration effectively replaces the state.[92]

Le Corbusier was heavily indebted to the thought of the 19th-century French utopians Saint-Simon and Charles Fourier. There is a noteworthy resemblance between the concept of the unité and Fourier's phalanstery.[93] From Fourier, Le Corbusier adopted at least in part his notion of administrative, rather than political, government.

Modulor

editThe Modulor was a standard model of the human form which Le Corbusier devised to determine the correct amount of living space needed for residents in his buildings. It was also his rather original way of dealing with differences between the metric system and the British or American system since the Modulor was not attached to either one.

Le Corbusier explicitly used the golden ratio in his Modulor system for the scale of architectural proportion. He saw this system as a continuation of the long tradition of Vitruvius, Leonardo da Vinci's "Vitruvian Man", the work of Leon Battista Alberti, and others who used the proportions of the human body to improve the appearance and function of architecture. In addition to the golden ratio, Le Corbusier based the system on human measurements, Fibonacci numbers, and the double unit. Many scholars see the Modulor as a humanistic expression but it is also argued that: "It's exactly the opposite (...) It's the mathematization of the body, the standardization of the body, the rationalization of the body."[94]

He took Leonardo's suggestion of the golden ratio in human proportions to an extreme: he sectioned his model human body's height at the navel with the two sections in golden ratio, then subdivided those sections in golden ratio at the knees and throat; he used these golden ratio proportions in the Modulor system.

Le Corbusier's 1927 Villa Stein in Garches exemplified the Modulor system's application. The villa's rectangular ground plan, elevation, and inner structure closely approximate golden rectangles.[95]

Le Corbusier placed systems of harmony and proportion at the centre of his design philosophy, and his faith in the mathematical order of the universe was closely bound to the golden section and the Fibonacci series, which he described as "rhythms apparent to the eye and clear in their relations with one another. And these rhythms are at the very root of human activities. They resound in Man by an organic inevitability, the same fine inevitability which causes the tracing out of the Golden Section by children, old men, savages, and the learned."[96]

Open Hand

editThe Open Hand (La Main Ouverte) is a recurring motif in Le Corbusier's architecture, a sign for him of "peace and reconciliation. It is open to give and open to receive." The largest of the many Open Hand sculptures that Le Corbusier created is a 26-meter-high (85 ft) version in Chandigarh, India, known as Open Hand Monument.

Furniture

editLe Corbusier was an eloquent critic of the finely crafted, hand-made furniture, made with rare and exotic woods, inlays and coverings, presented at the 1925 Exposition of Decorative Arts. Following his usual method, Le Corbusier first wrote a book with his theories of furniture, complete with memorable slogans. In his 1925 book L'Art Décoratif d'aujourd'hui, he called for furniture that used inexpensive materials and could be mass-produced. Le Corbusier described three different furniture types: type-needs, type-furniture, and human-limb objects. He defined human-limb objects as: "Extensions of our limbs and adapted to human functions that are type-needs and type-functions, therefore type-objects and type-furniture. The human-limb object is a docile servant. A good servant is discreet and self-effacing to leave his master free. Certainly, works of art are tools, beautiful tools. And long live the good taste manifested by choice, subtlety, proportion, and harmony". He further declared: "Chairs are architecture, sofas are bourgeois".[page needed]

Le Corbusier first relied on ready-made furniture from Thonet to furnish his projects, such as his pavilion at the 1925 Exposition. In 1928, following the publication of his theories, he began experimenting with furniture design. In 1928, he invited the architect Charlotte Perriand to join his studio as a furniture designer. His cousin, Pierre Jeanneret, also collaborated on many of the designs. For the manufacture of his furniture, he turned to the German firm Gebrüder Thonet, which had begun making chairs with tubular steel, a material originally used for bicycles, in the early 1920s. Le Corbusier admired the design of Marcel Breuer and the Bauhaus, who in 1925 had begun making sleek modern tubular club chairs. Mies van der Rohe had begun making his version in a sculptural curved form with a cane seat in 1927.[97]

The first results of the collaboration between Le Corbusier and Perriand were three types of chairs made with chrome-plated tubular steel frames: The LC4, Chaise Longue, (1927–28), with a covering of cowhide, which gave it a touch of exoticism; the Fauteuil Grand Confort (LC3) (1928–29), a club chair with a tubular frame which resembled the comfortable Art Deco club chairs that became popular in the 1920s; and the Fauteuil à dossier vascular (LC4) (1928–29), a low seat suspended in a tubular steel frame, also with cowhide upholstery. These chairs were designed specifically for two of his projects, the Maison la Roche in Paris and a pavilion for Barbara and Henry Church. All three clearly showed the influence of Mies van der Rohe and Marcel Breuer. The line of furniture was expanded with additional designs for Le Corbusier's 1929 Salon d'Automne installation, 'Equipment for the Home'. Despite the intention of Le Corbusier that his furniture should be inexpensive and mass-produced, his pieces were originally costly to make and were not mass-produced until many years later, when he was famous. [98]

Controversies

editThere is debate over the apparently variable or contradictory nature of Le Corbusier's political views.[99] In the 1920s, he co-founded and contributed articles about urbanism to the fascist journals Plans, Prélude and L'Homme Réel.[100][99] He also penned pieces in favour of Nazi antisemitism for those journals, as well as "hateful editorials".[101] Between 1925 and 1928, Le Corbusier had connections to Le Faisceau, a short-lived French fascist party led by Georges Valois. (Valois later became an anti-fascist.)[102] Le Corbusier knew another former member of Faisceau, Hubert Lagardelle, a former labor leader and syndicalist who had become disaffected with the political left. In 1934, after Lagardelle had obtained a position at the French embassy in Rome, he arranged for Le Corbusier to lecture on architecture in Italy. Lagardelle later served as minister of labor in the pro-Axis Vichy regime. While Le Corbusier sought commissions from the Vichy regime, particularly the redesign of Marseille after its Jewish population had been forcefully removed,[99] he was unsuccessful, and the only appointment he received from it was membership of a committee studying urbanism.[citation needed] Alexis Carrel, a eugenicist surgeon, appointed Le Corbusier to the Department of Bio-Sociology of the Foundation for the Study of Human Problems, an institute promoting eugenics policies under the Vichy regime.[99]

Le Corbusier has been accused of antisemitism. He wrote to his mother in October 1940, as the Vichy government enacted anti-Jewish laws: "The Jews are having a bad time. I occasionally feel sorry. But it appears their blind lust for money has rotted the country." He was also accused of belittling the Muslim population of Algeria, then part of France. When Le Corbusier proposed a plan for the rebuilding of Algiers, he condemned the existing housing for European Algerians, complaining that it was inferior to that inhabited by indigenous Algerians: "the civilized live like rats in holes" while "the barbarians live in solitude, in well-being."[103] His plan for rebuilding Algiers was rejected, and thereafter Le Corbusier mostly avoided politics.[104]

Criticism

editIn his eulogy to Le Corbusier at the memorial ceremony for the architect in the courtyard of the Louvre on 1 September 1965, French Culture Minister André Malraux declared, "Le Corbusier had some great rivals, but none of them had the same significance in the revolution of architecture, because none bore insults so patiently and for so long."[105]

Later criticism of Le Corbusier was directed at his ideas on urban planning. In 1998, the architectural historian Witold Rybczynski wrote in Time magazine:

"He called it the Ville Radieuse, the Radiant City. Despite the poetic title, his urban vision was authoritarian, inflexible and simplistic. Wherever it was tried—in Chandigarh by Le Corbusier himself or in Brasilia by his followers—it failed. Standardization proved inhuman and disorienting. The open spaces were inhospitable; the bureaucratically imposed plan was socially destructive. In the US, the Radiant City took the form of vast urban-renewal schemes and regimented public housing projects that damaged the urban fabric beyond repair. Today, these megaprojects are being dismantled, as superblocks give way to rows of houses fronting streets and sidewalks. Downtowns have discovered that combining, not separating, different activities is the key to success. So is the presence of lively residential neighbourhoods, old as well as new. Cities have learned that preserving history makes more sense than starting from zero. It has been an expensive lesson, and not one that Le Corbusier intended, but it too is part of his legacy."[106]

Technological historian and architecture critic Lewis Mumford wrote in Yesterday's City of Tomorrow that the extravagant heights of Le Corbusier's skyscrapers had no reason for existence apart from the fact that they had become technological possibilities. The open spaces in his central areas had no reason for existence either, Mumford wrote, since on the scale he imagined, there was no motive during the business day for pedestrian circulation in the office quarter. By "mating utilitarian and financial image of the skyscraper city to the romantic image of the organic environment, Le Corbusier had produced a sterile hybrid."

The public housing projects influenced by his ideas have been criticized for isolating poor communities in monolithic high-rises and breaking the social ties integral to a community's development. One of his most influential detractors has been Jane Jacobs, who delivered a scathing critique of Le Corbusier's urban design theories in her seminal work The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

For some critics, the urbanism of Le Corbusier was the model for a fascist state.[107] These critics cited Le Corbusier himself when he wrote that "not all citizens could become leaders. The technocratic elite, the industrialists, financiers, engineers, and artists would be located in the city centre, while the workers would be removed to the fringes of the city".[108]

Alessandro Hseuh-Bruni wrote in "Le Corbusier's Fatal Flaws – A Critique of Modernism" that

"In addition to setting the stage for infrastructural developments to come, Le Corbusier's blueprints and models, while not so well-regarded by urban planners and street dwellers alike, also examined the sociological side of cities in great detail. World War II left millions dead and transformed the urban landscape throughout much of Europe, from England to the Soviet Union, and housing on a mass scale was necessary. Le Corbusier personally took this as a challenge to accommodate the masses on an unprecedented scale. This mission statement manifested itself in the form of "Cité Radieuse" (The Radiant City), located in Marseille, France. The construction of this utopian sanctuary was dependent on the destruction of traditional neighbourhoods – he showed no regard for French cultural heritage and tradition. Entire neighbourhoods were ravaged to make way for these dense, uniform concrete blocks. If he had his way, Paris' elite Marais community would have been destroyed. In addition, the theme of segregation that plagued earlier models of Le Corbusier's continued in this supposed utopian vision, with the wealthy elite being the only ones to access the luxuries of modernism."[109]

Influence

editLe Corbusier was concerned about problems he saw in industrial cities at the turn of the 20th century. He thought industrial housing techniques led to crowding, dirtiness, and a lack of a moral landscape. He was a leader of the modernist movement to create better-living conditions and a better society through housing. Ebenezer Howard's Garden Cities of Tomorrow heavily influenced Le Corbusier and his contemporaries.[110]

Le Corbusier revolutionized urban planning, and was a founding member of the Congrès International d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM).[111] One of the first to realize how the automobile would change human society, Le Corbusier conceived the city of the future with large apartment buildings isolated in a park-like setting on pilotis. Le Corbusier's plans were adopted by builders of public housing in Europe and the United States. In Great Britain, urban planners turned to Le Corbusier's "Cities in the Sky" as a cheaper method of building public housing from the late 1950s.[112] Le Corbusier criticized any effort at ornamentation of the buildings.[75]

Several of the many architects who worked for Le Corbusier in his studio became prominent, including painter-architect Nadir Afonso, who absorbed Le Corbusier's ideas into his aesthetics theory. Lúcio Costa's city plan of Brasília and the industrial city of Zlín planned by František Lydie Gahura in the Czech Republic are based on his ideas. Le Corbusier's thinking had profound effects on city planning and architecture in the Soviet Union during the Constructivist era.[original research?]

Le Corbusier harmonized and lent credence to the idea of space as a set of destinations between which mankind moved continuously. He gave credibility to the automobile as a transporter and freeway in urban spaces. His philosophies were useful to urban real estate developers in the American post-World War II period because they justified and lent intellectual support to the desire to raze traditional urban spaces for high density, high-profit urban concentration. The freeways connected this new urbanism to low density, low cost, highly profitable suburban locales available to be developed for middle-class single-family housing.[original research?]

Missing from this scheme of movement was connectivity between isolated urban villages created for the lower-middle and working classes, and the destination points in Le Corbusier's plan: suburban and rural areas, and urban commercial centres. As designed, the freeways travelled over, at, or beneath grade levels of the living spaces of the urban poor, for example, the Cabrini–Green housing project in Chicago. Because such projects were devoid of freeway-exit ramps and were cut off by freeway rights-of-way, they became isolated from the jobs and services that had been concentrated at Le Corbusier's nodal transportation endpoints.[original research?]

As jobs migrated to the suburbs, these urban-village dwellers effectively found themselves stranded without freeway-access points in their communities or public mass transit that could economically reach suburban job centres. Late in the post-War period, suburban job centres found labour shortages to be such a critical problem that they sponsored urban-to-suburban shuttle-bus services to fill the vacant working-class and lower-middle-class jobs, which did not typically pay enough to afford car ownership.[original research?]