The Open Hand Monument is a symbolic structure designed by the architect Le Corbusier and located in the Capitol Complex of the Indian city and union territory of Chandigarh. It is the emblem and symbol of the Government of Chandigarh and symbolizes "the hand to give and the hand to take; peace and prosperity, and the unity of mankind".[1] The largest example of Le Corbusier's many Open Hand sculptures,[2] it stands 26 metres (85 ft) high. The metal structure with vanes is 14 metres (46 ft) high, weighs 50 short tons (100,000 lb), and was designed to rotate in the wind.[1][3][4]

| The open hand monument | |

|---|---|

The Open Hand Monument in Chandigarh, India | |

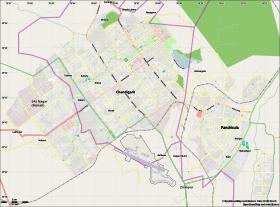

Location of Open Hand Monument in Chandigarh | |

| Artist | Le Corbusier |

| Year | 1964 |

| Dimensions | 26 m (85 ft) |

| Location | Chandigarh |

| 30°45′32″N 76°48′26″E / 30.758974°N 76.807348°E | |

Symbolism

editThe Open Hand (La Main Ouverte) in Chandigarh is a frequent theme in Le Corbusier's architecture, a symbol for him of "peace and reconciliation. It is open to give and open to receive". Le Corbusier also stated that it was a recurring idea that conveyed the "Second Machine Age".[2]

Location

editThe Open Hand is located in Sector 1 in the Capitol Complex of Chandigarh, on the backdrop of the Himalayan Shivalik hill range.[4][5]

Background

editLe Corbusier thought of the Open Hand Monument first in 1948,[6] "spontaneously, or more exactly, as a result of reflections and spiritual struggles arising from feelings of anguish and disharmony which separate mankind and so often create enemies".[7] His passion for the hand had an important role in his career beginning from the age of seventeen-and-a-half when he picked up a brick, a gesture which led to millions of bricks being laid in later years.[8] Jane Drew felt that the symbol of Le Corbusier's philosophy should be made evident to the people of Chandigarh. Le Corbusier then perceived it as a sculptural monument to be erected in Chandigarh, the city he is credited with planning, designing, and implementing. One of his associates, Jerzy Soltan, a member of his atelier, had deliberated with him as to the type of hand to be made – whether an open hand or a fist holding a fighting device.[7]

The Open Hand became a public project rather than a private symbol when Le Corbusier planned it for the city of Chandigarh, where his associate and cousin Pierre Jeanneret was then working as chief architect and town planning advisor to the Government of Punjab, and was supervising the construction of Chandigarh.[9] In case his preference for Chandigarh to erect the sculpture was not accepted, he had thought of an alternate location: the top of the Bhakra Dam, the 220 metres (720 ft) high dam in Nangal in Punjab.[8] He had planned to erect the Open Hand against the scenic background of the Himalayas. He called the location he had selected the "Pit of Contemplation" (Fosse de la Consideration). The design was a huge elevated object (a wind vane), which was an "inspirational symbol of humanity unarmed, fearless, and spiritually receptive".[9]

Le Corbusier had discussed this project with the then Prime Minister of India Jawaharlal Nehru when he had visited India in 1951. He had also written to Nehru, saying that since 1948 he had been obsessed with this symbol of the Open Hand which he wished to erect at the end of the capital (Chandigarh) in the foreground of the Himalayas. Nehru had concurred with the concept.[9] In his letter to Nehru, Le Corbusier expressed a view that it could also become a symbol of the Non Aligned Movement (NAM), an idea that Nehru mooted although ultimately it was not adopted for NAM.[3] Later, for Le Corbusier, the project had remained linked with Nehru, and on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of Nehru's birth in 1964, he was invited to submit something for a "celebratory volume". Le Corbusier forthwith sketched his concept of the Open Hand, for it was his recurring dream which had obsessed him for six years (prior to 1954). In the sketch, he conceived the Open Hand as a 26 metres (85 ft) high sculpture which would rotate with the wind and would shine with colours such as yellow, red, green, and white in the foreground of the mountain range.[9] Above the sketch he inscribed, "La Fin d'un monde" (The End of a World).[10]

In spite of his personal relations with the highest echelons of the Government of India, Le Corbusier faced the problem of finding funds for this "Utopian symbol of peace and reconciliation in a poor and remote though spiritually rich province". He then appealed to André Malraux to get it made as a gift of France. He even appealed to his friends in India to get his project through. In spite of these efforts, it was twenty years after his death in 1965 that the Open Hand, his dream project, was realized in 1985. It was built adjoining the location which had been intended for the governor's residence but which was later replaced by Le Corbusier's Museum of Knowledge.[11]

Features

editThe Open Hand Monument | |

|---|---|

| Rotation due to wind and comparison of size with people at base |

The Open Hand sculpture is 26 metres (85 ft) high above a trench of 12.5 by 9 metres (41 ft × 30 ft).[5] The metal wind vane, which is erected over a concrete platform, is 14 metres (46 ft) in height and weighs 50 tons; it appears like a flying bird.[12] The sculpture was hand-cast in sheet metal at the Bhakra Nangal Management Board's workshop at Nangal. The surface of the vane is covered with polished steel and is fitted over a steel shaft with ball bearings to facilitate free rotation by the wind.[5]

References

edit- ^ a b Betts & McCulloch 2014, p. 61-62.

- ^ a b Shipman 2014, p. 7.

- ^ a b Jarzombek & Prakash 2011, p. 1931.

- ^ a b "Capitol Complex". Tourism Department Government of Chandigarh.

- ^ a b c Sharma 2010, p. 132.

- ^ Corbusier & Žaknić1997, p. 129.

- ^ a b Corbusier & Žaknić1997, p. 6, 129.

- ^ a b Corbusier & Žaknić1997, p. 1964.

- ^ a b c d Corbusier & Žaknić1997, p. 6.

- ^ Corbusier & Žaknić1997, p. 7.

- ^ Corbusier & Žaknić1997, p. 6-7.

- ^ Betts & McCulloch 2014, p. 61.

Bibliography

edit- Betts, Vanessa; McCulloch, Victoria (10 February 2014). Delhi & Northwest India Footprint Focus Guide: Includes Amritsar, Shimla, Leh, Srinagar, Kullu Valley, Dharamshala. Footprint Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-909268-75-3.

- Corbusier, Le; Žaknić, Ivan (1997). Mise Au Point. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06353-0.

- Jarzombek, Mark M.; Prakash, Vikramaditya (4 October 2011). A Global History of Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-90248-6.

- Sharma, Sangeet (26 September 2010). Corb's Capitol: a journey through Chandigarh's architecture. A3 foundation. ISBN 978-81-8247-245-7.

- Shipman, Gertrude (5 October 2014). Ultimate Handbook Guide to Chandigarh : (India) Travel Guide. MicJames. pp. 7–. GGKEY:32JTRTZ290J.