The Roman campaigns in Germania (12 BC – AD 16) were a series of conflicts between the Germanic tribes and the Roman Empire. Tensions between the Germanic tribes and the Romans began as early as 17/16 BC with the Clades Lolliana, where the 5th Legion under Marcus Lollius was defeated by the tribes Sicambri, Usipetes, and Tencteri. Roman Emperor Augustus responded by rapidly developing military infrastructure across Gaul. His general, Nero Claudius Drusus, began building forts along the Rhine in 13 BC and launched a retaliatory campaign across the Rhine in 12 BC.

| Early imperial campaigns in Germania | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Roman–Germanic Wars | |||||||

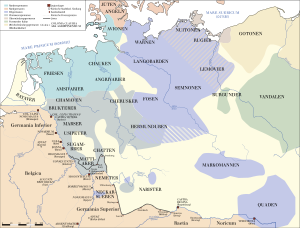

Map of Germania in AD 50 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Roman Empire | Germanic tribes | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Drusus (12–9 BC) Tiberius (8–7 BC, AD 4–5, and AD 11–12) Ahenobarbus (3–2 BC) Vinicius (2 BC–AD 4) Varus † (AD 9) Germanicus (AD 14–16) Flavus (AD 11–12, and AD 14–16) | Arminius (AD 9–16) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

Drusus led three more campaigns against the Germanic tribes in the years 11–9 BC. For the campaign of 10 BC, he was celebrated for being the Roman who traveled farthest east in northern Europe. Succeeding generals would continue attacking across the Rhine until AD 16, notably Publius Quinctilius Varus in AD 9. During the return trip from his campaign, Varus' army was ambushed and almost destroyed by a Germanic force led by Arminius at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest; Arminius was the leader of the Cherusci, had previously fought in the Roman army, and was considered by Rome to be an ally. Roman expansion into Germania Magna stopped as a result, and all campaigns immediately after were in retaliation of the Clades Variana ("Varian Disaster"), the name used by Roman historians to describe the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, and to prove that Roman military might could still overcome German lands. The last general to lead Roman forces in the region during this time was Germanicus, the adoptive son of Emperor Tiberius, who in AD 16 had launched the final major military expedition by Rome into Germania.

Background

editIn 27 BC, Augustus became princeps and sent Agrippa to quell the uprisings in Gallia. During the Gallic uprisings, weapons were smuggled into Gaul across the Rhine from Germania to supply the insurrection. At the time, Rome's military presence in the Rhineland was small and its only military operations there were punitive expeditions against incursions. It was seen as more important to secure Gaul and wipe out any signs of resistance there.[1][2]

After Gaul had been pacified, improvements were made to the infrastructure, including those to the Roman road network in 20 BC by Aggripa. Rome increased its military presence along the Rhine and several forts were constructed there between 19 and 17 BC. Augustus thought that the future prosperity of the Empire depended on the expansion of its borders, and Germania had become the next target for imperial expansion.[2][3]

After capturing and executing Roman soldiers east of the Rhine in 17/16 BC, the tribes Sicambri, Usipetes, and Tencteri crossed the river and attacked a Roman cavalry unit. Unexpectedly, they came across the 5th Legion under Marcus Lollius, whom they defeated and whose eagle they captured. This defeat convinced Augustus to reorganize and improve the military presence in Gaul in order to prepare the region for campaigns across the Rhine. An attack soon after by Lollius and Augustus caused the invaders to retreat back to Germania and sue for peace with Rome.[2]

From 16 to 13 BC, Augustus was active in Gaul. In preparation for the coming campaigns, Augustus established a mint at Lugdunum (Lyon) in Gaul, to supply a means of coining money to pay the soldiers, organized a census for collecting taxes from Gaul, and coordinated the establishment of military bases on the west bank of the Rhine.[2]

Campaigns before the Clades Variana

editCampaigns of Drusus

editNero Claudius Drusus, an experienced general and stepson of Augustus, was made governor of Gaul in 13 BC. The following year saw an uprising in Gaul – a response to the Roman census and taxation policy set in place by Augustus.[4] For most of the following year he conducted reconnaissance and dealt with supply and communications. He also had several forts built along the Rhine, including Argentoratum (Strasburg, France), Moguntiacum (Mainz, Germany), and Castra Vetera (Xanten, Germany).[5]

Drusus first saw action following an incursion by the Sicambri and the Usipetes into Gaul, which he repelled before launching a retaliatory attack across the Rhine. This marked the beginning of Rome's 28 years of campaigns across the lower Rhine.[4]

He crossed the Rhine with his army and invaded the land of the Usipetes. He then marched north against the Sicambri and pillaged their lands. Travelling down the Rhine and landing in what is now the Netherlands, he conquered the Frisians, who thereafter served in his army as allies. Then, he attacked the Chauci, who lived in northwestern Germany in what is now Lower Saxony. Around winter, he recrossed the Rhine, and returned to Rome.[6]

The following spring, Drusus began his second campaign across the Rhine. He first subdued the Usipetes, and then marched east to the Visurgis (Weser River). Then, he passed through the territory of the Cherusci, whose territory stretched from the Ems to the Elbe, and pushed as far east as the Weser. This was the furthest east into northern Europe that a Roman general had ever traveled, a feat which won him much renown. Between depleted supplies and the coming winter, he decided to march back to friendly territory. On the return trip, Drusus' legions were nearly destroyed at Arbalo by Cherusci warriors taking advantage of the terrain to harass them.[7]

He was made consul for the following year, and it was voted that the doors to the Temple of Janus be closed, a sign the empire was at peace. However, peace did not last, for in the spring of 10 BC, he once again campaigned across the Rhine and spent the majority of the year attacking the Chatti. In his third campaign, he conquered the Chatti and other German tribes, and then returned to Rome, as he had done before at the end of the campaign season.[8]

In 9 BC, he began his fourth campaign, this time as consul. Despite bad omens, Drusus again attacked the Chatti and advanced as far as the territory of the Suebi, in the words of Cassius Dio, "conquering with difficulty the territory traversed and defeating the forces that attacked him only after considerable bloodshed."[9] Afterwards, he once again attacked the Cherusci, and followed the retreating Cherusci across the Weser River, and advanced as far as the Elbe, "pillaging everything in his way", as Cassius Dio puts it. Ovid states that Drusus extended Rome's dominion to new lands that had only been discovered recently. On his way back to the Rhine, Drusus fell from his horse and was badly wounded. His injury became seriously infected, and after thirty days, Drusus died from the disease, most likely gangrene.[10]

When Augustus learned Drusus was sick, he sent Tiberius to quickly go to him. Ovid states Tiberius was at the city of Pavia at the time, and when he had learned of his brother's condition, he rode to be at his dying brother's side. He arrived in time, but it wasn't long before Drusus drew his last breath.[11]

Campaigns of Tiberius, Ahenobarbus and Vinicius

editAfter Drusus' death, Tiberius was given command of the Rhine's forces and waged two campaigns within Germania over the course of 8 and 7 BC. He marched his army between the Rhine and the Elbe, and met little resistance except from the Sicambri. Tiberius came close to exterminating the Sicambri, and had those who survived transported to the Roman side of the Rhine, where they could be watched more closely. Velleius Paterculus portrays Germany as essentially conquered,[12] and Cassiodorus writing in the 6th century AD asserts that all Germans living between the Elbe and the Rhine had submitted to Roman power. However, the military situation in Germany was very different from what was suggested by imperial propaganda.[13][14]

Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus was appointed as the commander in Germany by Augustus in 6 BC, and three years later, in 3 BC, he reached and crossed the Elbe with his army. Under his command causeways were constructed across the bogs somewhere in the region between the Ems and the Rhine, called pontes longi. The next year, conflicts between the Rome and the Cherusci flared up. While the elite members of one faction sought stronger ties with Roman leaders, the Cherusci as a whole would continue to resist for the next twenty years. Although Ahenobarbus had marched to the Elbe and directed the construction of infrastructure in the region east of the Rhine, he did not do well against the Cherusci warrior bands, who he tried to handle like Tiberius had the Sicambri. Augustus recalled Ahenobarbus to Rome in 2 BC and replaced him with a more seasoned military commander, Marcus Vinicius.[13][14]

Between 2 BC and AD 4, Vinicius commanded the 5 legions stationed in Germany. At around the time of his appointment, many of the Germanic tribes arose in what the historian Velleius Paterculus calls the "vast war". However, no account of this war exists. Vinicius must have performed well, for he was awarded the ornamenta triumphalia on his return to Rome.[13][15][16]

Again in AD 4, Augustus sent Tiberius to the Rhine frontier as the commander in Germany. He campaigned in northern Germany for the next two years. During the first year, he conquered the Canninefati, the Attuarii, the Bructeri, and subdued the Cherusci. Soon thereafter, he declared the Cherusci "friends of the Roman people."[17] In AD 5, he campaigned against the Chauci, and then coordinated an attack into the heart of Germany both overland and by river. The Roman fleet and legions met on the Elbe, whereupon Tiberius departed from the Elbe to march back westward at the end of the summer without stationing occupying forces at this eastern position. This accomplished a demonstration to his troops, to Rome, and to the German peoples that his army could move largely unopposed through Germany, but like Drusus, he did nothing to hold territory. Tiberius' forces were attacked by German troops on the way west back to the Rhine, but successfully defended themselves.[14][18]

The elite of the Cherusci tribe came to be special friends of Rome after Tiberius's campaigns of AD 5. In the preceding years, a power struggle had resulted in the alliance of one party with Rome. In this tribe was a ruling lineage that played a critical role in forging this friendship between the Cherusci and Rome. Belonging to this elite clan, was the young Arminius, who was around twenty-two at the time. Membership in this clan gave him special favor with Rome. Tiberius lent support to this ruling clan to gain control over the Cherusci, and he granted the tribe a free status among the German peoples. To keep an eye on the Cherusci, Tiberius had a winter base built on the Lippe.[19]

It was Roman opinion that by AD 6 the German tribes had largely been pacified, if not conquered. Only the Marcomanni, under king Maroboduus, remained to be subdued. Rome planned a massive pincer attack against them involving 12 legions from Germania, Illyricum, and Rhaetia, but when word of an uprising in Illyricum arrived the attack was called off and concluded peace with Maroboduus, recognizing him as king.[20][21][22]

Part of the Roman strategy was to resettle troublesome tribal peoples, to move them to locations where Rome could keep better tabs on them and away from their regular allies. Tiberius resettled the Sicambri, who had caused particular problems for Drusus, in a new site west of the Rhine, where they could be watched more closely.[18]

Campaign of Varus

editPrelude

editAlthough it was assumed that the province of Germania Magna had been pacified, and Rome had begun integrating the region into the empire, there was a risk of rebellion during the military subjugation of a province. Following Tiberius's departure to Illyricum, Augustus appointed Publius Quinctilius Varus to the German command, as he was an experienced officer, but not the great military leader a serious threat would warrant.[23]

Varus imposed civic changes on the Germans, including a tax – what Augustus expected any governor of a subdued province to do. However, the Germanic tribes began rallying around a new leader, Arminius of the Cherusci. Arminius, who Rome considered an ally, and who had fought in the Roman army before.[24] He accompanied Varus, who was in Germania with the Legions XVII, XVIII, and XIX to finish the conquest of Germania.[25]

Not much is known of the campaign of AD 9 until the return trip, when Varus left with his legions from their camp on the Weser. On their way back to Castra Vetera, Varus received reports from Arminius that there was a small uprising west of the Roman camp. The Romans were on the way back to the Rhine anyway, and the small revolt would only be a small detour – about two days away. Varus departed to deal with the revolt believing that Arminius would ride ahead to garner the support of his tribesmen for the Roman cause. In reality, Arminius was actually preparing an ambush. Varus took no extra precautions on the march to quell the uprising, as he was expecting no trouble.[26]

Victory of Arminius

editArminius' revolt came during the Pannonian revolt, at a time when the majority of Rome's legions were tied down in Illyricum. Varus only had three legions, which were isolated in the heart of Germany.[27] Scouts were sent ahead of Roman forces as the column approached Kalkriese. Scouts were local Germans as they would have had knowledge of the terrain, and so would had to have been a part of Arminius' ploy. Indeed, they reported that the path ahead was safe. Historians Wells and Abdale say that the scouts likely alerted the Germans to the advancing column, giving them time to get into position.[28][29]

The Roman column followed the road going north until it began to wrap around a hill. The hill was to the west of the road and was wooded. There was boggy terrain all around the hill, woodland to the east, and a swamp to the north (out of sight of the Roman column until they reached the bend taking the road southwest around the hill's northeastern point).[30] Roman forces continued along the sloshy sandbank at the base of the hill until the front of the column was attacked. They heard loud shouting and spears began falling on them from the woody slope to their left. Spears then began falling from the woods to their right and the front fell into disorder from panic.[31] The surrounded soldiers were unable to defend themselves because they were marching in close formation and the terrain was too muddy for them to move effectively.[32]

Within ten minutes, word reached the middle of the column where Varus was. Communication was hampered by the column being packed densely in the narrow road. Not knowing the full extent of the attack, Varus ordered his forces to advance forward to reinforce his forces at the front. This pushed the soldiers at the front further into the enemy, and thousands of German warriors began to pour out of the woods to attack up close. The soldiers at the middle and rear of the column began to flee in all directions, but most of them were caught in the bog or killed. Varus realized the severity of his situation and killed himself with his sword. A few Romans survived and made their way back to the winter quarters at Xanten by staying hidden and carefully travelling through the forests.[33]

Campaigns after the Clades Variana

editCampaigns of Tiberius

editIt had become clear that German lands had not been pacified. After word reached Rome of Varus' defeat, Augustus had Tiberius sent back to the Rhine to stabilize the frontier in AD 10. Tiberius increased the defensive capabilities of the Rhine fortifications and redistributed forces across the region. He began to improve discipline and led small attacks across the Rhine. Velleius reports Tiberius as having enormous success. He says Tiberius:[34][35]

penetrat interius, aperit limites, vastat agros, urit domos, fundit obvios maximaque cum gloria, incolumi omnium, quos transduxerat, numero in hiberna revertitur.[35] |

penetrated into the heart of the country, opened up military roads, devastated fields, burned houses, routed those who came against him, and, without loss to the troops with which he had crossed, he returned, covered with glory, to winter quarters.[34] |

| —Velleius Paterculus 2.120.2 | —Wells 2003, p. 202 |

According to Seager and Wells, Velleius' account is almost certainly an exaggeration.[34][35] Seager says that Tiberius successfully applied tactics that he had developed in Illyricum, but that his attacks were "no more than punitive raids". Tiberius did not get far in his conquest of Germany, because he was moving slowly as to not risk wasting lives. His advance was cautious and deliberate: he ravaged crops, burned dwellings, and dispersed the population. Suetonius reports that Tiberius' orders were given in writing and that he was to be consulted directly on any doubtful points.[36][37]

Tiberius was joined by his adoptive son Germanicus for the campaigns of AD 11 and 12. The two generals crossed the Rhine and made various excursions into enemy territory, moving with the same caution as Tiberius had the year before. The campaigns were conducted against the Bructeri and the Marsi to avenge the defeat of Varus, but had no significant effect. However, the campaign, combined with Rome's alliance to the Marcommanic federation of Marbod, prevented the Germanic coalition, led by Arminius, from crossing the Rhine to invade Gaul and Italy. In the winter of AD 12, Tiberius and Germanicus returned to Rome.[38][39][40][41]

Campaigns of Germanicus

editAugustus appointed Germanicus commander of the forces in the Rhine the following year. In August AD 14, Augustus died and on 17 September the senate met to confirm Tiberius as princeps.[42] Roman writers, including Tacitus and Cassius Dio, mention that Augustus left a statement ordering the end of imperial expansion. It's not known if Augustus actually made such an order, or if Tiberius found it necessary to stop Roman expansion as the costs were too great, both financially and militarily.[43]

About one-third of Rome's total military forces, eight legions, were stationed in the Rhine following their redeployment by Tiberius. Four were in lower Germany under Aulus Caecina (the 5th and 21st at Xanten; the 1st and 20th at or near Cologne). Another four were in upper Germany under Gaius Silius (the 2nd, 13th, 16th, and 14th).[44]

Between AD 14 and 16, Germanicus led Roman armies across the Rhine into Germany against the forces of Arminius and his allies. Germanicus made great use of the navy, which he needed for logistics given the lack of roads in Germany at the time. The war culminated in AD 16 with the decisive victories of Battle of Idistaviso and Angrivarian Wall in which the Germanic coalition under Arminius was destroyed. Arminius himself barely managed to survive the conflict. Rome handed annexed lands over to friendly chieftains and withdrew from most of Germany, as they felt the military effort required to continue was too great in comparison to any potential gain.[45] Tacitus says the purpose of the campaigns was to avenge the defeat of Varus, rather than to expand Rome's borders.[44]

Aftermath

editTiberius decided to suspend all military activities beyond the Rhine, leaving the German tribes to dispute over their territories and fight amongst each other. He was content favoring alliances with certain tribes over the others in order to maintain their conflicts against each other. He achieved less of his objectives in direct involvement than he had with diplomatic relations. In general, it was too risky to go beyond the Rhine, and it was too costly in economic and military resources than Rome could recover even if they had conquered all the lands between the Rhine and the Elbe.[45]

It is possible that a new attempt to invade Germania took place during the reign of Claudius, with the expedition of Corbulo in 47, which was stopped in its tracks after initial successes against the Frisians and Chaucis.[46][47] It is not until Domitian that new territories were acquired, between the high valleys of the Rhine and the Danube, following the campaigns carried out by his generals between 83 and 85 (in what was called the Agri Decumates).[48] In 85, lands on the western side of the Rhine were organized into the Roman provinces of Germania Inferior and Germania Superior,[49] while the province of Raetia had been established to the south in what is now Bavaria, Switzerland and Austria in 15 BC.[50] The Roman Empire would launch no other major incursion into Germania Magna until Marcus Aurelius (r. 161–180) during the Marcomannic Wars.[51]

References

edit- ^ Abdale 2016, p. 72

- ^ a b c d Wells 2003, p. 77

- ^ Abdale 2016, p. 73

- ^ a b Wells 2003, p. 155

- ^ Abdale 2016, p. 74

- ^ Abdale 2016, pp. 74–5

- ^ Wells 2003, pp. 155–6

- ^ Abdale 2016, pp. 75–6

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History 55, 1

- ^ Wells 2003, pp. 156–7

- ^ Abdale 2016, pp. 76–7

- ^ Wells 2003, pp. 157

- ^ a b c Lacey & Murray 2013, p. 68

- ^ a b c Wells 2003, p. 158

- ^ Velleius Paterculus, Compendium of Roman History 2, 104

- ^ Syme 1939, p. 401

- ^ Lacey & Murray 2013, pp. 68–69

- ^ a b Wells 2003, p. 159

- ^ Wells 2003, pp. 158–9

- ^ Velleius Paterculus, Compendium of Roman History 2, 109, 5; Cassius Dio, Roman History 55, 28, 6–7

- ^ Lacey & Murray 2013, p. 69

- ^ Wells 2003, p. 160

- ^ Lacey & Murray 2013, pp. 69–70

- ^ Wells 2003, pp. 205–8

- ^ Wells 2003, pp. 25–6

- ^ Wells 2003, p. 26

- ^ Lacey & Murray 2013, p. 71

- ^ Wells 2003, p. 169

- ^ Abdale 2016, pp. 162–3

- ^ Wells 2003, p. 166

- ^ Wells 2003, p. 170

- ^ Wells 2003, p. 171

- ^ Wells 2003, pp. 174–175

- ^ a b c Wells 2003, p. 202

- ^ a b c Seager 2008, p. 36

- ^ Suetonius, Tiberius 18.2

- ^ Seager 2008, pp. 36–7

- ^ Cassius Dio, LVI, 25

- ^ Wells 2003, pp. 203

- ^ Seager 2008, p. 37

- ^ Gibson 2013, pp. 80–82

- ^ Levick 1999, pp. 50–53

- ^ Wells 2003, p. 203

- ^ a b Wells 2003, p. 204

- ^ a b Wells 2003, pp. 206–207

- ^ Tacitus, Annals 11, 18–20

- ^ Renucci 2012, pp. 189–192

- ^ Jones 1992, p. 130

- ^ Rüger 2004, pp. 527–28

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Raetia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 812–813.

- ^ Phang et al. 2016, p. 940

Bibliography

editPrimary sources

edit- Cassius Dio, Roman History Book 55, English translation

- Velleius Paterculus, Roman History Book II, Latin text with English translation

Secondary sources

edit- Abdale, Jason R. (2016), Four Days in September: The Battle of Teutoburg, Pen & Sword Military, ISBN 978-1-4738-6085-8

- Gibson, Alisdair (2013), The Julio-Claudian Succession: Reality and Perception of the "Augustan Model", Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-23191-7

- Jones, Brian W. (1992), The Emperor Domitian, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-10195-0

- Kehne, Peter (1998), "Germanicus", Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA) 11: 438–448

- Levick, Barbara (1999), Tiberius the Politician, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-21753-8

- Renucci, Pierre (2012), Claude, l'empereur inattendu (in French), Perrin, ISBN 978-2-262-03779-6

- Seager, Robin (2008), Tiberius, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-470-77541-7

- Syme, Ronald (1939), The Roman Revolution, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-881001-8

- Wells, Peter S. (2003), The Battle That Stopped Rome, Norton, ISBN 978-0-393-32643-7

- Lacey, James; Murray, Williamson (2013), Moment of Battle: The Twenty Clashes that Changed the World, Bantam Books, ISBN 978-0-345-52697-7

- Rüger, C. (2004) [1996], "Germany", in Bowman, Alan K.; Champlin, Edward; Lintott, Andrew (eds.), The Cambridge Ancient History: X, The Augustan Empire, 43 B.C. – A.D. 69, vol. 10 (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-26430-3

- Phang, Sara E.; Spence, Iain; Kelly, Douglas; Londey, Peter (2016), Conflict in Ancient Greece and Rome: The Definitive Political, Social, and Military Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-61069-020-1