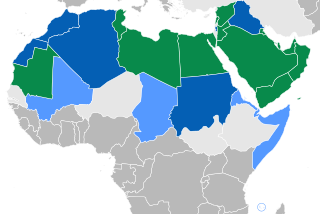

Economic history of the Arab world addresses the history of economic activity in the Arabic-speaking countries and the stretching of Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Arabian Sea in the east, and from the Mediterranean Sea in the north to the Horn of Africa and the Indian Ocean in the southeast from the time of its origins in the Arabian peninsula and spread in the 7th century CE Muslim conquests and since.

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (August 2024) |

The regions conquered in the Muslim conquest included rich farming regions in the Maghreb, the Nile Valley and the Fertile Crescent. As is true of the world as a whole, agriculture dominated the economy until the modern period, with livestock grazing playing a particularly large role in the Arab world. Significant trade routes included the Silk Road, the spice trade, and the trade in gold, salt, slaves and luxury goods including ivory and feathers out of sub-Saharan Africa.

Important pre-modern industries included tanning, pottery, and metalwork.

The map of IPS school

editThe Ips school ran from all over the Arabian peninsula to southwest Mongolia. This made it easier for trade and travel for students.

West Africa

editAround the 9th century, The Arab people understood the significance of gold and its economic impact.[1] Arabs participated in the gold trade, specifically within the Ghana goldfields near the 9th century.[2] The people of Ghana also participated in the gold trade from its beginning and began to purposefully dominate this trade.[3] North African regions financially expanded as well due to their shipping of gold to various territories.[3] Gold was a commodity to the Arabs near the 8th Century, which Africa would supply.[4] Gold was good for the economic growth of the Arab people.[5] As silver was declining in worth, the access to gold allowed the economic value of silver to be saved.[5]

Mansa Musa

editMansa Musa, a leader from West Africa, impacted the Arab world with the vast amount of gold he transported to Mecca during a religious pilgrimage.[6] During his trip, he proved extravagant with his gold.[6] Although he is not said to have traded his gold, Mansa Musa proved his wealth to the Meccans by handing out the gold he brought on his trip.[6] Mansa Musa and his people specifically harmed the Cairo economy due to the tremendous amount of gold they spread in the area.[7]

The economic importance of the Hajj

editTrade was allowed on the Hajj and often those on it would have to trade along the way in order to finance their lengthy travels.[8] Typically, money was brought along to give to the Bedouin tribes as well as to the holy cities which the pilgrims would journey through.[9] During the Ottoman Empire's control, these goods would be taxed. The level of taxes rose sharply under Hussein. These levels were lowered when Ibn Saud took power.[9] Merchants would also participate in the Hajj as this allowed them to receive protection from the guards who accompanied pilgrims on the Hajj.[8] Their trading in the regions along the pilgrimage often provided numerous economic benefits to those regions.[9] This allowed the merchant caravans to become more successful and helped make them a greater part of the economy of the Arab world.[8] When Hajj travelers returned to their native lands, they would often bring goods with them which would cause shifts in designs, raising prices, as well as bringing back items to sell directly.[10]

Transportation

editThe pilgrims of the Hajj first traveled by Muslim state-sponsored caravans, but these were replaced by European-owned steam ships in the later 19th century, which increased the number of travelers but put the transportation industry of the Hajj in non-Muslim hands.[9] In 1908, the Ottoman Empire built a train system, returning some control of the industry to Muslims.[9]

Past In more recent years, Saudi Arabia has seen an increase in revenue due to the tourism industry during the Hajj. In 1994, the Saudi government emphasized tourism as a way to increase their economy.[8] In 2000 it was estimated that nearly sixty percent of all tourism in Saudi Arabia came for the Hajj or the similar ‘Umrah.[8] Over 40 percent of money spent by tourists being for the Hajj or the ‘Umrah.[8] The increase in the tourism industry during the Hajj has helped to solve the country's large segment of unemployed foreign workers from other countries[8] such as from Egypt and India.[8]

Jizya

editJizyah is what is taken from the People of the Book (people of Abrahamic faith and followers of the books revealed to them) – and from the mushrikeen (people who worship anything apart from the One God), according to some scholars – every year, in return for their being allowed to settle in Muslim lands, and in return for protecting them against those who would commit aggression against them. These people would not be required to pay the obligatory Zakaat (annual tax) that Muslims would need to pay.

The word jizyah comes from the word jazaa’ (recompense). It is as if it is a recompense for allowing them to live in the land and for protecting their lives, property and dependents.

However, the exact meaning of the Jizya is debated. It is mentioned in the Qur'an as part of the law, but the interpretation of the law has varied throughout time by the Muslims.[11][12] Possible interpretations of the Jizya, and execution of these interpretations, have included a collective tribute, a poll tax, and a discriminatory tax.[11][13] One argument pertaining to the purpose of the Jizya is that it had nothing to do with discrimination, but only helped the government keep tabs on the population, and maintain a structured society.[12] This argument, however, contradicts what is stated in the Qur'an’s verses about the Jizya. These verses give the idea of the Jizya as an act of humiliation and ethnic diversion.[12] The Jizya used to be a tribute required of non-Muslim people under the protection of the Muslims, which gave this lesser group or society, unable to protect themselves from outside Muslim opposition, the option to submit to the Muslim people and come under their protection. In return for this protection, the minority people are required to pay a tribute to the Muslim government.[12] The Jizya often provided a source of child support for the Muslims to continue their raids and expansion in the form of Jihads.[12]

Swahili Coast

editEarly history

editTrade along the Swahili coast dates back to the 1st century C.E. and up to the 19th century C.E. Though there are not many reliable written records of trade along the East African coast between the 1st and 11th centuries, trade still occurred between the Indian Ocean coast (Azania) and the rest of the world (India, China and Arabian countries). Interaction between these areas was assisted by the knowledge of the monsoon winds by traders who traveled the Indian Ocean.[14]

From the 11th century to the 19th century, the spread of Islam greatly influenced trade on the Swahili coast,

Arab presence

editArabic presence along the Swahili coast began with the migration of Arabs from Arabia to the East African coast as a result of demographic and political struggles in Arabia. Later in the 8th century, trade along the coast was influenced by the majority of Muslim visitors to the coast of East Africa. This trade fueled the development of coastal port towns such as Mogadishu, Mombasa, and Kilwa and also the growth of the Swahili language, which became the lingua franca between local Bantu people and Arab immigrants.[15]

Omani Arabs

editOne of the major Arabic influences along the Swahili coast was the arrival of the Omani Arabs. Renowned as great mariners, the Omani traders were well known along the Indian Ocean. The arrival of the Omani Arabs along the east African coast in the late 17th century replaced the Portuguese influence along the Swahili Coast after their defeat at Mombasa.[16] Trade along the Swahili coast increased with the Omani Arabs' domination of the area. The development of Zanzibar between 1804 and 1856 increased the economic development of the Swahili coast due to its role as an importer of ivory and slaves from the African interior, through long-distance trading.[17] The Omani traders then exported slaves and ivory from the East African coast due to a high demand in Europe and India.[18] The availability of slaves made them a suitable source of labor on the growing clove plantations of Zanzibar and Pemba and thus further increased the demand for slaves along the coast, which stimulated long-distance trading within Eastern and Central Africa. Some of these slaves were bought as household slaves in the Swahili Arabs homes.[18]

Trade with the African interior

editTrading along the Swahili coast between the Swahili-Arabs and interior tribes stimulated the development of the Interior African tribes. Because of the expansion of trade within the African interior, African rulers started developing politically with an aim to expand their kingdoms and territories in order to be able to have control of the trade routes and mineral sources within their territories. Due to the interaction between the Swahili-Arab traders and interior African tribes, Islam also spread as a religious language. The reign of the Sultans of Zanzibar between 1804 - 1888 and their dominion of the East African Coast from Somalia to Mozambique greatly influenced trade along the Swahili Coast.[17]

Tippu Tip and the slave trade

editBefore the abolition of slave trade in 1873, when a Proclamation of the prohibition of slave trafficking from the interior to the coast was issued, Tippu Tip was among the best known Swahili-Arab traders. Having set out from Zanzibar in his conquest to obtain Ivory, he defeated Nsama of Trowa and established his own rule in Manyema country in order to control the ivory and slave trade.[17]

Waqf

editA Waqf is a charitable endowment given by Muslims to help benefit their societies,[19] which had a major role in the economy, the development of cities, and travel.[20] Typically, a Waqf took the form of rulers creating something for the benefit of their people.[19] It required creating something that would be a source of renewable revenue and directing that revenue towards something, be it a specific individual, the community, or the local mosque so long as it brought one closer to God.[21] Schools were also beneficiaries of Waqf due to Islam viewing education as a form of worship.[22] The individual making a Waqf was not expected to benefit except in the spiritual sense.[21] The Waqf was a pivotal part of building infrastructure as it would often lead to an increase in the number of businesses surrounding the endowed institution.[21] Waqfs were also used to protect cities in warfare, such as the Citadel of Qaitbay, which was built to defend Alexandria in the mid-fifteenth century.[22] While controversial, cash was also sometimes used as a form of Waqf with the interest on it supporting the beneficiaries.[20]

Egypt

editIn Egypt, the Mamluks practiced Waqf, seeing it as a way of keeping their property safe from government hands and as a way of transferring the bulk of their wealth to their children, going around the laws that prevented this directly.[19] This became problematic in the 14th century when soldiers in the Egyptian army were rewarded by giving them temporary fiefs. Many of these were turned into Waqfs by their owners, however, meaning the Mamluk government could no longer reclaim them for redistribution. This would affect the size of the army. In 1378-79, Barquq argued this was causing harm to the state and used this as a justification for dissolving the agrarian Waqfs.[22] Waqfs also served as a way for the Mamluk converts to Islam to demonstrate their faith by participating in it.[19] It also provided a way for the Mamluk rulers to demonstrate their power and wealth.[19] Waqf would become more popular under the Ottoman rulers in later years.[19]

Criticism

editThe Waqf enables a wealthy founder to insure the economic well-being of his descendants by the mechanism of donating his estate to a waqf or trust for the support of a madrasah. The founder could legally appoint himself and his heirs as professor of law and headmaster, a position that can be passed down through the family in perpetuity and one that had the important function of insuring the ongoing prominence of a man and his descendants while "sheltering family assets" from taxation.[23][24] The Waqf was often used in this way by families to keep money within the immediate family.[25] In the 19th century in Tripoli, Waqf was often used to benefit the nuclear family, excluding the extended family that would have gotten a share of the wealth had the normal inheritance laws been followed.[19] Because of this, the Waqf has been criticized for allowing wealth to be maintained by the few.[26]

Some argue that the waqf contributed to the ossification of science in the Muslim world because the law of waqf "permitted little deviation form the original founder's stipulations."[23]

Piracy

editThe small Muslim states on the Persian Gulf and the coast of the Maghreb were supported by a unique economic model of piracy in which the ruler regularly plundered merchant ships and launched Razzias, raids, the coasts of non-Muslim lands as far off as Ireland and Iceland to capture slaves.[27] The slaves could be profitably sold or chained as slave oarsmen to the pirate galleys, pulling the oars that powered the attacks that captured more slaves. Ship owners or their governments could pay protection money to avoid capture.

Raiding

editSome Arabs practiced Razzias, or caravan raiding. They led armed men to attack and plunder passing caravans.[28]: 128 This economic model remained popular among Muslim tribes for many centuries.[28]: 26 Merchants could pay protection money to the caravan raiders.

Another model of Arab raiding was practiced by armed nomadic Bedouin tribes who attacked settled farmers; initially Christians in the early centuries, but later also Muslim villages. This was a successful and steady income model, especially since the villagers would pay protection money and save the Bedouin the trouble and risk of actual fighting.[29]

Slavery

editOil

editThe discovery of large petroleum deposits in the early 20th century revolutionized the economy of much of the region, particularly the states of Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Kuwait, and Qatar surrounding the Persian Gulf, which are among the top oil or gas exporters worldwide. Algeria, Libya, Egypt, Tunisia, and Sudan all have smaller but significant reserves.

East Africa

editEastern Africa, more specifically Sudan, positioned itself for growth through the oil trade.[30] With a sense of possible hope for Sudanese economic profit, Arabs financed manufactory motives in Sudan, expanding products to help industrialize Sudan during the late 20th century.[30] Despite the Arabs placing finances within Sudan territory, this seemed to have caused more issues as Ethiopians swarmed into Sudan, putting Sudan in a financially tough situation.[30]

Nigeria

editNigerian history of oil imports from the Middle East shows a reliance on Iranian oil during the 1970s.[31]

References

edit- ^ Falola, Toyin (2002). Key Events in African History: A Reference Guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313313233.

- ^ Stapleton, Timothy J. (2013-10-21). A Military History of Africa [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313395703.

- ^ a b Middleton, John (2015). World Monarchies and Dynasties. Routledge. ISBN 9781317451587.

- ^ Beckles, Hilary; Shepherd, Verene (2007). Trading Souls: Europe's Transatlantic Trade in Africans. Ian Randle Publishers. ISBN 9789766373061.

- ^ a b Adas, Michael (2001). Agricultural and Pastoral Societies in Ancient and Classical History. Temple University Press. ISBN 9781566398329.

- ^ a b c Sardar, Ziauddin (2014-10-21). Mecca: The Sacred City. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 164. ISBN 9781620402665.

164.

- ^ Conrad, David C. (2009). Empires of Medieval West Africa: Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781604131642.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Daher, Rami (2007). Tourism in the Middle East : continuity, change and transformation. Clevedon: Channel View Publications. ISBN 9781845410513. OCLC 83977214.

- ^ a b c d e Tagliacozzo, Eric; Toorawa, Shawkat M. (2016). The Hajj : pilgrimage in Islam. New York, NY. ISBN 9781107030510. OCLC 934585969.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Triaud, Jean-Louis; Villalón, Leonardo Alfonso (2009). Economie morale et mutations de l'islam en Afrique subsaharienne. Vol. 231. Bruxelles: Éd. De Boeck. ISBN 9782804102395. OCLC 690793981.

- ^ a b Cohen, Mark R. (1994). Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages. Princeton University Press. ISBN 069101082X.

- ^ a b c d e Emon, Anver M. (2012-07-26). Religious Pluralism and Islamic Law: Dhimmis and Others in the Empire of Law. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780199661633.

- ^ Stillman, Norman A. (1979). The Jews of Arab Lands. Jewish Publication Society. p. 159. ISBN 9780827611559.

jizya.

- ^ Maxon, Robert M. (2009). East Africa : an introductory history (3rd and revised ed.). Morgantown: West Virginia University Press. ISBN 978-1933202464. OCLC 794702218.

- ^ Martin, B. G. (1974). "Arab Migrations to East Africa in Medieval Times". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 7 (3): 367–390. doi:10.2307/217250. JSTOR 217250.

- ^ Gavin, Thomas (2011). The Rough Guide to Oman. London: Rough Guides. ISBN 9781405389358. OCLC 759806997.

- ^ a b c Tidy, Michael; Leeming, Donald (1980). A History of Africa, 1840–1914: 1840–1880. Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 9780340244197.

- ^ a b Cooper, Frederick (1997). Plantation slavery on the east coast of Africa. Portsmouth, N.H.: Heinemann. ISBN 0435074199. OCLC 36430607.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ghazaleh, Pascale, ed. (2011). Held in trust: Waqf in the Islamic world. Cairo, Egypt. ISBN 9789774163937. OCLC 893685769.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Singer, Amy (2002). Constructing Ottoman beneficence : an imperial soup kitchen in Jerusalem. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780585471198. OCLC 53093194.

- ^ a b c Hoexter, Miriam; Eisenstadt, S. N. (Shmuel Noah); Levtzion, Nehemia (2002). The public sphere in Muslim societies. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780791453674. OCLC 53226174.

- ^ a b c Lev, Yaacov (2005). Charity, endowments, and charitable institutions in medieval Islam. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. ISBN 9780813035895. OCLC 670429590.

- ^ a b Toby E. Huff, The Rise of Early Modern Science; Islam China and the West, second edition, Cambridge University Press, 1993, 2003, p. 77.

- ^ Chamberlain, Michael, Knowledge and Social Practice in Medieval Damascus, 1190–1350, Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- ^ Powers, David (October 1999). "The Islamic Family Endowment (Waqf)". Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law. 32 (4).

- ^ Sait, Siraj; Lim, Hilary (2006). Land, law and Islam: property and human rights in the Muslim world. London: Zed Books. ISBN 9781842778104. OCLC 313730507.

- ^ "British Slaves on the Barbary Coast".

- ^ a b The historical Muhammad, Irving M. Zeitlin, Polity, 2007

- ^ J. Ginat, Anatoly Michailovich Khazanov, Changing Nomads in a Changing World, Sussex Academic Press, 1998, p. 193.

- ^ a b c Dumper, Michael; Stanley, Bruce E. (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 299. ISBN 9781576079195.

- ^ South Africa: Time Running Out : the Report of the Study Commission on U.S. Policy Toward Southern Africa. University of California Press. 1981. ISBN 9780520045477.

Further reading

edit- K. N. Chaudhuri (1999). "The Economy in Muslim Societies, chapter 5". In Francis Robinson (ed.). The Cambridge illustrated history of the Islamic world. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66993-1.

- K. N. Chaudhuri (1985) Trade and civilisation in the Indian Ocean: an economic history from the rise of Islam to 1750 CUP.

- Nelly Hanna, ed. (2002). Money, land and trade: an economic history of the Muslim Mediterranean. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-699-7.

- Zvi Yehuda Hershlag (1980). Introduction to the modern economic history of the Middle East. Brill Archive. ISBN 978-90-04-06061-6.

- Timur Kuran (2011). The Long Divergence: How Islamic Law Held Back the Middle East. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14756-7. This is mostly about the (perceived) economic downsides of Islamic law and its (alleged) historical impact; Review in The Independent

- M. A. Cook, ed. (1970). Studies in the economic history of the Middle East: from the rise of Islam to the present day. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-19-713561-7. (A collection of essay on various topics roughly organized by historical period.)

- William Montgomery Watt; Pierre Cachia (1996). A history of Islamic Spain. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0847-8., chapter 4, The Gradeur of the Umayyad Caliphate; section 2: The economic basis.

- Mohammed A. Bamyeh (1999). The social origins of Islam: mind, economy, discourse. U of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-3263-3. Chapter 2: Socioeconomy and the Horizon of Thought; covers the early socioeconomic history of the Arabian Peninsula