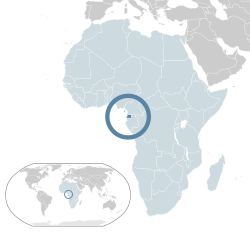

Equatorial Guinea,[a] officially the Republic of Equatorial Guinea,[b] is a country on the west coast of Central Africa, with an area of 28,000 square kilometres (11,000 sq mi). Formerly the colony of Spanish Guinea, its post-independence name refers to its location near both the Equator and in the African region of Guinea. As of 2024[update], the country had a population of 1,795,834,[7] over 85% of whom are members of the Fang people, the country's dominant ethnic group. The Bubi people, indigenous to Bioko, are the second largest group at approximately 6.5% of the population.

Republic of Equatorial Guinea

| |

|---|---|

| Motto: Unidad, Paz, Justicia (Spanish) "Unity, Peace, Justice" | |

| Anthem: Caminemos pisando las sendas de nuestra inmensa felicidad (Spanish) Let Us Walk Treading the Paths of Our Immense Happiness | |

| Capital | Malabo (current) Ciudad de la Paz (under construction) 3°45′N 8°47′E / 3.750°N 8.783°E |

| Largest city | Malabo, Bata |

| Official languages | |

| Recognised regional languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2020[3]) | |

| Religion (2020)[4] |

|

| Demonym(s) | |

| Government | Unitary dominant-party presidential republic under a totalitarian dictatorship[5][6] |

| Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo | |

| Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue | |

| Manuel Osa Nsue Nsua | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| Chamber of Deputies | |

| Independence from Spain | |

• Declared | 12 October 1968 |

| Area | |

• Total | 28,050 km2 (10,830 sq mi) (141st) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | 1,795,834 [7] (154th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| HDI (2022) | medium (133rd) |

| Currency | Central African CFA franc (XAF) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (WAT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | +240 |

| ISO 3166 code | GQ |

| Internet TLD | .gq |

| |

Equatorial Guinea consists of two parts, an insular and a mainland region. The insular region consists of the islands of Bioko (formerly Fernando Pó) in the Gulf of Guinea and Annobón, a small volcanic island which is the only part of the country south of the equator. Bioko Island is the northernmost part of Equatorial Guinea and is the site of the country's capital, Malabo. The Portuguese-speaking island nation of São Tomé and Príncipe is located between Bioko and Annobón.

The mainland region, Río Muni, is bordered by Cameroon to the north and Gabon to the south and east. It is the location of Bata, Equatorial Guinea's second largest city, and Ciudad de la Paz, the country's planned future capital. Río Muni also includes several small offshore islands, such as Corisco, Elobey Grande, and Elobey Chico. The country is a member of the African Union, Francophonie, OPEC, and the CPLP.

After becoming independent from Spain in 1968, Equatorial Guinea was ruled by Francisco Macías Nguema. He declared himself president for life in 1972, but was overthrown in a coup in 1979 by his nephew, Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, who has served as the country's president since. Both presidents have been widely characterized as dictators by foreign observers. Since the mid-1990s, Equatorial Guinea has become one of sub-Saharan Africa's largest oil producers.[10] It has subsequently become the richest country per capita in Africa,[11] and its gross domestic product (GDP) adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP) per capita ranks 43rd in the world;[12] however, the wealth is distributed extremely unevenly, with few people benefiting from the oil riches. The country ranks 144th on the 2019 Human Development Index,[13] with less than half the population having access to clean drinking water and 7.9% of children dying before the age of five.[14][15] Equatorial Guinea's nominal GDP per capita is $10,982 in 2021 according to OPEC.[16]

Since Equatorial Guinea is a former Spanish colony, Spanish is the main official language. French and (as of 2010[update]) Portuguese have also been made official,[17] but they are not as widely used. Aside from the partially recognized Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, it is the only country situated in Mainland Africa in where Spanish is an official language (Spanish is also spoken in the African parts of Spain: the Canary Islands, Ceuta and Melilla).[18] It is also the most widely spoken language (considerably more than the other two official languages); according to the Instituto Cervantes, 87.7% of the population has a good command of Spanish.[19]

Equatorial Guinea's government is totalitarian and has one of the worst human rights records in the world, consistently ranking among the "worst of the worst" in Freedom House's annual survey of political and civil rights.[20] Reporters Without Borders ranks Obiang among its "predators" of press freedom.[21] Human trafficking is a significant problem, with the U.S. Trafficking in Persons Report identifying Equatorial Guinea as a source and destination country for forced labour and sex trafficking. The report also noted that Equatorial Guinea "does not fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking but is making significant efforts to do so."[22]

History

editPygmies probably once lived in the continental region that is now Equatorial Guinea, but are today found only in isolated pockets in southern Río Muni. Bantu migrations likely started around 2,000 BC from between south-east Nigeria and north-west Cameroon (the Grassfields).[23] They must have settled continental Equatorial Guinea around 500 BC at the latest.[24][25] The earliest settlements on Bioko Island are dated to AD 530.[26] The Annobón population, originally native to Angola, was introduced by the Portuguese via São Tomé island.[citation needed]

First European contact and Portuguese rule (1472–1778)

editThe Portuguese explorer Fernando Pó, seeking a path to India, is credited as being the first European to see the island of Bioko, in 1472. He called it Formosa ("Beautiful"), but it quickly took on the name of its European discoverer. Fernando Pó and Annobón were colonized by Portugal in 1474. The first factories were established on the islands around 1500 as the Portuguese quickly recognized the positives of the islands including volcanic soil and disease-resistant highlands. Despite natural advantages, initial Portuguese efforts in 1507 to establish a sugarcane plantation and town near what is now Concepción on Fernando Pó failed due to Bubi hostility and fever.[27] The main island's rainy climate, extreme humidity and temperature swings took a major toll on European settlers from the beginning, and it would be centuries before attempts restarted.[citation needed]

Early Spanish rule and lease to Britain (1778–1844)

editIn 1778, Queen Maria I of Portugal and King Charles III of Spain signed the Treaty of El Pardo which ceded Bioko, adjacent islets, and commercial rights to the Bight of Biafra between the Niger and Ogoue rivers to Spain in exchange for large areas in South America that are now Western Brazil. Brigadier Felipe José, Count of Arjelejos formally took possession of Bioko from Portugal on 21 October 1778. After sailing for Annobón to take possession, the Count died of disease caught on Bioko and the fever-ridden crew mutinied. The crew landed on São Tomé instead where they were imprisoned by the Portuguese authorities after having lost over 80% of their men to sickness.[28] As a result of this disaster, Spain was thereafter hesitant to invest heavily in its new possession. However, despite the setback Spaniards began to use the island as a base for slave trading on the nearby mainland. Between 1778 and 1810, the territory of what became Equatorial Guinea was administered by the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, based in Buenos Aires.[29]

Unwilling to invest heavily in the development of Fernando Pó, from 1827 to 1843, the Spanish leased a base at Malabo on Bioko to the United Kingdom which it had sought as part of its efforts to suppress the transatlantic slave trade.[30] Without Spanish permission, the British moved the headquarters of the Mixed Commission for the Suppression of Slave Traffic to Fernando Pó in 1827, before moving it back to Sierra Leone under an agreement with Spain in 1843. Spain's decision to abolish slavery in 1817 at British insistence damaged the colony's perceived value to the authorities and so leasing naval bases was an effective revenue earner from an otherwise unprofitable possession.[29] An agreement by Spain to sell its African colony to the British was cancelled in 1841 due to metropolitan public opinion and opposition by Spanish Congress.[31]

Late 19th century (1844–1900)

editIn 1844, the British returned the island to Spanish control and the area became known as the "Territorios Españoles del Golfo de Guinea". Due to epidemics, Spain did not invest much in the colony, and in 1862, an outbreak of yellow fever killed many of the whites that had settled on the island. Despite this, plantations continued to be established by private citizens through the second half of the 19th century.[32]

The plantations of Fernando Pó were mostly run by a black Creole elite, later known as Fernandinos. The British settled some 2,000 Sierra Leoneans and freed slaves there during their rule, and a trickle of immigration from West Africa and the West Indies continued after the British left. A number of freed Angolan slaves, Portuguese-African creoles and immigrants from Nigeria, and Liberia also began to be settled in the colony, where they quickly began to join the new group.[33] To the local mix were added Cubans, Filipinos, Jews and Spaniards of various colours, many of whom had been deported to Africa for political or other crimes, as well as some settlers backed by the government.[34]

By 1870, the prognosis of whites that lived on the island was much improved after recommendations that they live in the highlands, and by 1884 much of the minimal administrative machinery and key plantations had moved to Basile hundreds of meters above sea level. Henry Morton Stanley had labeled Fernando Pó "a jewel which Spain did not polish" for refusing to enact such a policy. Despite the improved survival chances of Europeans living on the island, Mary Kingsley, who was staying on the island, still described Fernando Pó as "a more uncomfortable form of execution" for Spaniards appointed there.[32]

There was also a trickle of immigration from the neighboring Portuguese islands, escaped slaves, and prospective planters. Although a few of the Fernandinos were Catholic and Spanish-speaking, about nine-tenths of them were Protestant and English-speaking on the eve of the First World War, and pidgin English was the lingua franca of the island. The Sierra Leoneans were particularly well placed as planters while labor recruitment on the Windward coast continued. The Fernandinos became traders and middlemen between the natives and Europeans.[33] A freed slave from the West Indies by way of Sierra Leone named William Pratt established the cocoa crop on Fernando Pó.[35]

Early 20th century (1900–1945)

editSpain had not occupied the large area in the Bight of Biafra to which it had right by treaty, and the French had expanded their occupation at the expense of the territory claimed by Spain. Madrid only partly backed the explorations of men like Manuel Iradier who had signed treaties in the interior as far as Gabon and Cameroon, leaving much of the land out of "effective occupation" as demanded by the terms of the 1885 Berlin Conference. Minimal government backing for mainland annexation came as a result of public opinion and a need for labour on Fernando Pó.[36]

The eventual treaty of Paris in 1900 left Spain with the continental enclave of Río Muni, only 26,000 km2 out of the 300,000 stretching east to the Ubangi river which the Spaniards had initially claimed.[37] The humiliation of the Franco-Spanish negotiations, combined with the disaster in Cuba led to the head of the Spanish negotiating team, Pedro Gover y Tovar, committing suicide on the voyage home on 21 October 1901.[38] Iradier himself died in despair in 1911; decades later, the port of Cogo was renamed Puerto Iradier in his honour.[citation needed]

Land regulations issued in 1904–1905 favoured Spaniards, and most of the later big planters arrived from Spain after that.[citation needed] An agreement was made with Liberia in 1914 to import cheap labor. Due to malpractice however, the Liberian government eventually ended the treaty after revelations about the state of Liberian workers on Fernando Pó in the Christy Report which brought down the country's president Charles D. B. King in 1930.[citation needed]

By the late nineteenth century, the Bubi were protected from the demands of the planters by Spanish Claretian missionaries, who were very influential in the colony and eventually organised the Bubi into little mission theocracies reminiscent of the famous Jesuit reductions in Paraguay. Catholic penetration was furthered by two small insurrections in 1898 and 1910 protesting conscription of forced labour for the plantations. The Bubi were disarmed in 1917, and left dependent on the missionaries.[37] Serious labour shortages were temporarily solved by a massive influx of refugees from German Kamerun, along with thousands of white German soldiers who stayed on the island for several years.[38]

Between 1926 and 1959, Bioko and Río Muni were united as the colony of Spanish Guinea. The economy was based on large cacao and coffee plantations and logging concessions and the workforce was mostly immigrant contract labour from Liberia, Nigeria, and Cameroun.[39] Between 1914 and 1930, an estimated 10,000 Liberians went to Fernando Po under a labour treaty that was stopped altogether in 1930.[40] With Liberian workers no longer available, planters of Fernando Po turned to Río Muni. Campaigns were mounted to subdue the Fang people in the 1920s, at the time that Liberia was beginning to cut back on recruitment. There were garrisons of the colonial guard throughout the enclave by 1926, and the whole colony was considered 'pacified' by 1929.[41]

The Spanish Civil War had a major impact on the colony. A group of 150 Spanish whites, including the Governor-General and Vice-Governor-General of Río Muni, created a socialist party called the Popular Front in the enclave which served to oppose the interests of the Fernando Pó plantation owners. When the War broke out Francisco Franco ordered Nationalist forces based in the Canaries to ensure control over Equatorial Guinea. In September 1936, Nationalist forces backed by Falangists from Fernando Pó, similarly to what happened in Spain proper, took control of Río Muni, which under Governor-General Luiz Sanchez Guerra Saez and his deputy Porcel had backed the Republican government. By November, the Popular Front and its supporters had been defeated and Equatorial Guinea secured for Franco. The commander in charge of the occupation, Juan Fontán Lobé, was appointed Governor-General by Franco and began to exert more Spanish control over the enclave interior.[42]

Río Muni officially had a little over 100,000 people in the 1930s; escape into Cameroun or Gabon was easy. Fernando Pó thus continued to suffer from labour shortages. The French only briefly permitted recruitment in Cameroun, and the main source of labour came to be Igbo smuggled in canoes from Calabar in Nigeria. This resolution led to Fernando Pó becoming one of Africa's most productive agricultural areas after the Second World War.[37]

Final years of Spanish rule (1945–1968)

editPolitically, post-war colonial history has three fairly distinct phases: up to 1959, when its status was raised from "colonial" to "provincial", following the approach of the Portuguese Empire; between 1960 and 1968, when Madrid attempted a partial decolonisation aimed at keeping the territory as part of the Spanish system; and from 1968 on, after the territory became an independent republic. The first phase consisted of little more than a continuation of previous policies; these closely resembled the policies of Portugal and France, notably in dividing the population into a vast majority governed as 'natives' or non-citizens, and a very small minority (together with whites) admitted to civic status as emancipados, assimilation to the metropolitan culture being the only permissible means of advancement.[43]

This "provincial" phase saw the beginnings of nationalism, but chiefly among small groups who had taken refuge from the Caudillo's paternal hand in Cameroun and Gabon. They formed two bodies: the Movimiento Nacional de Liberación de la Guinea (MONALIGE), and the Idea Popular de Guinea Ecuatorial (IPGE). By the late 1960s, much of the African continent had been granted independence. Aware of this trend, the Spanish began to increase efforts to prepare the country for independence. The gross national product per capita in 1965 was $466, which was the highest in black Africa; the Spanish constructed an international airport at Santa Isabel, a television station and increased the literacy rate to 89%. In 1967, the number of hospital beds per capita in Equatorial Guinea was higher than Spain itself, with 1637 beds in 16 hospitals. By the end of colonial rule, the number of Africans in higher education was in only the double digits.[44]

A decision of 9 August 1963, approved by a referendum of 15 December 1963, gave the territory a measure of autonomy and the administrative promotion of a 'moderate' group, the Movimiento de Unión Nacional de Guinea Ecuatorial (MUNGE). This was unsuccessful, and, with growing pressure for change from the UN, Madrid was gradually forced to give way to the currents of nationalism. Two General Assembly resolutions were passed in 1965 ordering Spain to grant independence to the colony, and in 1966, a UN Commission toured the country before recommending the same thing. In response, the Spanish declared that they would hold a constitutional convention on 27 October 1967 to negotiate a new constitution for an independent Equatorial Guinea. The conference was attended by 41 local delegates and 25 Spaniards. The Africans were principally divided between Fernandinos and Bubi on one side, who feared a loss of privileges and 'swamping' by the Fang majority, and the Río Muni Fang nationalists on the other. At the conference, the leading Fang figure, the later first president Francisco Macías Nguema, gave a controversial speech in which he claimed that Adolf Hitler had "saved Africa".[45] After nine sessions, the conference was suspended due to deadlock between the "unionists" and "separatists" who wanted a separate Fernando Pó. Macías resolved to travel to the UN to bolster international awareness of the issue, and his firebrand speeches in New York contributed to Spain naming a date for both independence and general elections. In July 1968 virtually all Bubi leaders went to the UN in New York to try and raise awareness for their cause, but the world community was uninterested in quibbling over the specifics of colonial independence. The 1960s were a time of great optimism over the future of the former African colonies, and groups that had been close to European rulers, like the Bubi, were not viewed positively.[46]

Independence under Macías (1968–1979)

editIndependence from Spain was gained on 12 October 1968, at noon in the capital, Malabo. The new country became the Republic of Equatorial Guinea (the date is celebrated as the country's Independence Day[47]). Macías became president in the country's only free and fair election to date.[48] The Spanish (ruled by Franco) had backed Macías in the election; much of his campaigning involved visiting rural areas of Río Muni and promising that they would have the houses and wives of the Spanish if they voted for him. He had won in the second round of voting.

During the Nigerian Civil War, Fernando Pó was inhabited by many Biafra-supporting Ibo migrant workers and many refugees from the breakaway state fled to the island. The International Committee of the Red Cross began running relief flights out of Equatorial Guinea, but Macías quickly shut the flights down, refusing to allow them to fly diesel fuel for their trucks nor oxygen tanks for medical operations. The Biafran separatists were starved into submission without international backing.[49]

After the Public Prosecutor complained about "excesses and maltreatment" by government officials, Macías had 150 alleged coup-plotters executed in a purge on Christmas Eve 1969, all of whom were political opponents.[50] Macias Nguema further consolidated his totalitarian powers by outlawing opposition political parties in July 1970 and making himself president for life in 1972.[51][52] He broke off ties with Spain and the West. In spite of his condemnation of Marxism, which he deemed "neo-colonialist", Equatorial Guinea maintained special relations with communist states, notably China, Cuba, East Germany and the USSR. Macias Nguema signed a preferential trade agreement and a shipping treaty with the Soviet Union. The Soviets also made loans to Equatorial Guinea.[53] The shipping agreement gave the Soviets permission for a pilot fishery development project and also a naval base at Luba. In return, the USSR was to supply fish to Equatorial Guinea. China and Cuba also gave different forms of financial, military, and technical assistance to Equatorial Guinea, which got them a measure of influence there. For the USSR, there was an advantage to be gained in the war in Angola from access to Luba base and later on to Malabo International Airport.[53]

In 1974, the World Council of Churches affirmed that large numbers of people had been murdered since 1968 in an ongoing reign of terror. A quarter of the entire population had fled abroad, they said, while 'the prisons are overflowing and to all intents and purposes form one vast concentration camp'. Out of a population of 300,000, an estimated 80,000 were killed.[54] Apart from allegedly committing genocide against the ethnic minority Bubi people, Macias Nguema ordered the deaths of thousands of suspected opponents, closed down churches and presided over the economy's collapse as skilled citizens and foreigners fled the country.[55]

Obiang (1979–present)

editThe nephew of Macías Nguema, Teodoro Obiang deposed his uncle on 3 August 1979, in a bloody coup d'état; over two weeks of civil war ensued until Macías Nguema was captured. He was tried and executed soon afterward, with Obiang succeeding him as a less bloody, but still authoritarian president.[56]

In 1995, Mobil, an American oil company, discovered oil in Equatorial Guinea. The country subsequently experienced rapid economic development, but earnings from the country's oil wealth have not reached the population and the country ranks low on the UN human development index. 7.9% of children die before the age of 5, and more than 50% of the population lacks access to clean drinking water.[15] President Teodoro Obiang is widely suspected of using the country's oil wealth to enrich himself[57] and his associates. In 2006, Forbes estimated his personal wealth at $600 million.[58]

In 2011, the government announced it was planning a new capital for the country, named Oyala.[59][60][61][62] The city was renamed Ciudad de la Paz ("City of Peace") in 2017.

As of February 2016[update], Obiang is Africa's second-longest serving dictator after Cameroon's Paul Biya.[63] Equatorial Guinea was elected as a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council 2018–2019.[64] On 7 March 2021, there were munition explosions at a military base near the city of Bata, causing 98 deaths and 600 people being injured and treated at the hospital.[65] In November 2022, Obiang was re-elected in the 2022 Equatorial Guinean general election with 99.7% of the vote amid accusations of fraud by the opposition.[66][67]

Government and politics

editThe current president of Equatorial Guinea is Teodoro Obiang. The 1982 constitution of Equatorial Guinea gives him extensive powers, including naming and dismissing members of the cabinet, making laws by decree, dissolving the Chamber of Representatives, negotiating and ratifying treaties and serving as commander in chief of the armed forces.[citation needed] According to Human Rights Watch, the dictatorship of President Obiang used an oil boom to entrench and enrich itself further at the expense of the country's people.[68] Since August 1979, some 12 perceived unsuccessful coup attempts have occurred.[69] According to a March 2004 BBC profile,[70] politics within the country were dominated by tensions with Obiang's son, Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue.

In 2004, a planeload of suspected mercenaries was intercepted in Zimbabwe while allegedly on the way to overthrow Obiang. A November 2004 report[71] named Mark Thatcher as a financial backer of the 2004 Equatorial Guinea coup d'état attempt organized by Simon Mann. Various accounts also named the United Kingdom's MI6, the United States' CIA, and Spain as tacit supporters of the coup attempt.[72] Nevertheless, the Amnesty International report released in June 2005 on the ensuing trial of those allegedly involved highlighted the prosecution's failure to produce conclusive evidence that a coup attempt had actually taken place.[73] Simon Mann was released from prison on 3 November 2009 for humanitarian reasons.[74]

Since 2005, Military Professional Resources Inc., a US-based international private military company, has worked in Equatorial Guinea to train police forces in appropriate human rights practices. In 2006, US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice hailed Obiang as a "good friend" despite repeated criticism of his human rights and civil liberties record. The US Agency for International Development entered into a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Obiang in April 2006 to establish a social development fund in the country, implementing projects in the areas of health, education, women's affairs and the environment.[75]

In 2006, Obiang signed an anti-torture decree banning all forms of abuse and improper treatment in Equatorial Guinea, and commissioned the renovation and modernization of Black Beach prison in 2007 to ensure the humane treatment of prisoners.[76] However, human rights abuses have continued. Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International among other non-governmental organizations have documented severe human rights abuses in prisons, including torture, beatings, unexplained deaths and illegal detention.[77][78] Obiang was re-elected to serve an additional term in 2009 in an election the African Union deemed "in line with electoral law".[79] Obiang re-appointed Prime Minister Ignacio Milam Tang in 2010.[80]

In November 2011, a new constitution was approved. The vote on the constitution was taken, though neither the text nor its content was revealed to the public before the vote. Under the new constitution, the president was limited to a maximum of two seven-year terms and would be both the head of state and head of the government, therefore eliminating the prime minister. The new constitution also introduced the figure of a vice president and called for the creation of a 70-member senate with 55 senators elected by the people and the 15 remaining designated by the president. In the following cabinet reshuffle, it was announced that there would be two vice-presidents in clear violation of the constitution that was just taking effect.[82]

In October 2012, during an interview with Christiane Amanpour on CNN, Obiang was asked whether he would step down at the end of the current term (2009–2016) since the new constitution limited the number of terms to two and he has been reelected at least 4 times. Obiang answered he refused to step aside because the new constitution was not retroactive and the two-term limit would only become applicable from 2016.[83]

The elections on 26 May 2013 combined the senate, lower house and mayoral contests in a single package. Like all previous elections, this was denounced by the opposition, and it too was won by Obiang's PDGE. During the electoral contest, the ruling party hosted internal elections, which were later scrapped. Clara Nsegue Eyi and Natalia Angue Edjodjomo, coordinators of the Movimiento de Protesta Popular (People's Protest Movement), were arrested. They were detained on 13 May. They called for a peaceful protest at the Plaza de la Mujer square on 15 May. Coordinator Enrique Nsolo Nzo was also arrested and taken to Malabo Central Police Station. Nsolo Nzo was released later that day without charge.[84]

Shortly after the elections, opposition party Convergence for Social Democracy (CPDS) announced that they were going to protest peacefully against the 26 May elections on 25 June.[85] Interior minister Clemente Engonga refused to authorise the protest on the grounds that it could "destabilize" the country and CPDS decided to go forward, claiming constitutional right. On the night of 24 June, the CPDS headquarters in Malabo were surrounded by heavily armed police officers to keep those inside from leaving and thus effectively blocking the protest. Several leading members of CPDS were detained in Malabo and others in Bata were kept from boarding several local flights to Malabo.[86]

In 2016, Obiang was reelected for an additional seven-year term in an election that, according to Freedom House, was plagued by police violence, detentions and torture against opposition factions.[87]

Following the 2022 general elections, President Obiang's Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea holds all of the 100 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and all of those in the Senate. The opposition is almost non-existent in the country and is organized from Spain mainly within the social-democratic Convergence for Social Democracy. Most of the media are under state control; the private television channels, those of the Asonga group, belong to the president's family.[88]

In their 2020 publishing, Transparency International awarded Equatorial Guinea a total score of 16 on their Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). CPI ranks countries by their perceived level of public corruptionwhere zero is very corrupt and 100 is extremely clean. Equatorial Guinea was the 174th lowest scoring nation out of a total of 180 countries.[89] Freedom House, a pro-democracy and human rights NGO, described Obiang as one of the world's "most kleptocratic living autocrats", and complained about the US government welcoming his administration and buying oil from it.[90] According to 2023 V-Dem Democracy indices, Equatorial Guinea is the 7th least democratic country in Africa.[91]

Armed forces

editThe Armed Forces of Equatorial Guinea consists of approximately 2,500 service members.[92] The army has almost 1,400 soldiers, the police 400 paramilitary men, the navy 200 service members, and the air force about 120 members. There is also a gendarmerie, but the number of members is unknown.[93]

According to the 2024 Global Peace Index, Equatorial Guinea is the 94th most peaceful country in the world.[94]

Geography

editEquatorial Guinea is on the west coast of Central Africa. The country consists of a mainland territory, Río Muni, which is bordered by Cameroon to the north and Gabon to the east and south, and five small islands, Bioko, Corisco, Annobón, Elobey Chico (Small Elobey), and Elobey Grande (Great Elobey). Bioko, the site of the capital, Malabo, lies about 40 kilometers (25 mi) off the coast of Cameroon. Annobón Island is about 350 kilometers (220 mi) west-south-west of Cape Lopez in Gabon. Corisco and the two Elobey islands are in Corisco Bay, on the border of Río Muni and Gabon.

Equatorial Guinea lies between latitudes 4°N and 2°S, and longitudes 5° and 12°E. Despite its name, no part of the country's territory lies on the equator—it is in the northern hemisphere, except for the insular Annobón Province, which is about 155 km (96 mi) south of the equator.

Climate

editEquatorial Guinea has a tropical climate with distinct wet and dry seasons. From June to August, Río Muni is dry and Bioko wet; from December to February, the reverse occurs. In between it, there is a gradual transition. Rain or mist occurs daily on Annobón, where a cloudless day has never been registered. The temperature at Malabo, Bioko, ranges from 16 °C (61 °F) to 33 °C (91 °F), though on the southern Moka Plateau, normal high temperatures are only 21 °C (70 °F). In Río Muni, the average temperature is about 27 °C (81 °F). Annual rainfall varies from 1,930 mm (76 in) at Malabo to 10,920 mm (430 in) at Ureka, Bioko, but Río Muni is somewhat drier.

Ecology

editEquatorial Guinea spans several ecoregions. Río Muni region lies within the Atlantic Equatorial coastal forests ecoregion except for patches of Central African mangroves on the coast, especially in the Muni River estuary. The Cross-Sanaga-Bioko coastal forests ecoregion covers most of Bioko and the adjacent portions of Cameroon and Nigeria on the African mainland, and the Mount Cameroon and Bioko montane forests ecoregion covers the highlands of Bioko and nearby Mount Cameroon. The São Tomé, Príncipe, and Annobón moist lowland forests ecoregion covers all of Annobón, as well as São Tomé and Príncipe.[95]

The country had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.99/10, ranking it 30th globally out of 172 countries.[96]

- Ecology of Equatorial Guinea

-

Near Ciudad de la Paz

Wildlife

editEquatorial Guinea is home to gorillas, chimpanzees, various monkeys, leopards, buffalo, antelope, elephants, hippopotamuses, crocodiles, and various snakes, including pythons.[97]

- Wildlife of Equatorial Guinea

Administrative divisions

edit

Equatorial Guinea is divided into eight provinces.[98][99] The newest province is Djibloho, created in 2017 with its headquarters at Ciudad de la Paz, the country's future capital.[100][101] The eight provinces are as follows (numbers correspond to those on the map; provincial capitals appear in parentheses):[98]

- Annobón (San Antonio de Palé)

- Bioko Norte (Malabo)

- Bioko Sur (Luba)

- Centro Sur (Evinayong)

- Djibloho (Ciudad de la Paz)

- Kié-Ntem (Ebebiyín)

- Litoral (Bata)

- Wele-Nzas (Mongomo)

The provinces are further divided into 19 districts and 37 municipalities.[102]

Economy

editBefore the nation's independence from Spain, Equatorial Guinea exported cocoa, coffee and timber, mostly to its colonial ruler, Spain, but also to Germany and the UK. On 1 January 1985, the country became the first non-Francophone African member of the franc zone, adopting the CFA franc as its currency. The national currency, the ekwele, had previously been linked to the Spanish peseta.[103]

The discovery of large oil reserves in 1996 and its subsequent exploitation contributed to a dramatic increase in government revenue. As of 2004[update],[104] Equatorial Guinea is the third-largest oil producer in Sub-Saharan Africa. Its oil production has risen to 360,000 barrels per day (57,000 m3/d), up from 220,000 only two years earlier. Oil companies operating in Equatorial Guinea include ExxonMobil, Marathon Oil, Kosmos Energy and Chevron.[105][106]

In July 2004, the United States Senate published an investigation into Riggs Bank, a Washington-based bank into which most of Equatorial Guinea's oil revenues were paid until recently, and which also banked for Chile's Augusto Pinochet. The Senate report showed at least $35 million siphoned off by Obiang, his family and regime senior officials. The president has denied any wrongdoing. Riggs Bank in February 2005 paid $9 million in restitution for Pinochet's banking, no restitution was made with regard to Equatorial Guinea.[107]

Forestry, farming, and fishing are also major components of the country's gross domestic product (GDP). Subsistence farming predominates. Agriculture is the country's main source of employment, providing income for 57% of rural households and employment for 52% of the workforce.[108] From 2000 to 2010, Equatorial Guinea had the highest average annual increase in GDP, 17%.[109]

Equatorial Guinea is a member of the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA).[110] Equatorial Guinea is also a member of the Central African Monetary and Economic Union (CEMAC), a subregion that comprises more than 50 million people.[111] Equatorial Guinea tried to be validated as an Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI)-compliant country. The country obtained candidate status on 22 February 2008; when Equatorial Guinea applied to extend the deadline for completing EITI's validation, the EITI Board did not agree to the extension.[112]

According to the World Bank, Equatorial Guinea has the highest gross national income (GNI) per capita of any African country, 83 times larger than the GNI per capita of Burundi, the poorest country.[113] However, Equatorial Guinea has extreme poverty brought about by wealth inequality.[114][115] According to the 2016 United Nations Human Development Report, Equatorial Guinea had a GDP per capita of $21,517, one of the highest levels of wealth in Africa. However, it is one of the most unequal countries in the world according to the Gini index, with 70 per cent of the population living on one dollar a day.[116] The country ranks 145th out of 189 on the United Nations Human Development Index in 2019.[88]

Hydrocarbons account for 97% of the state's exports, and it is a member of the African Petroleum Producers Organization. In 2020, it faces its eighth year of recession, due in part to endemic corruption.[88] The economy of Equatorial Guinea was expected to grow about 2.6% in 2021, a projection that was based on the successful completion of a large gas project and the recovery of the world economy by the second half of the year. But the country is expected to return to recession in 2022, with a real GDP decline of about 4.4%.[117] In 2022, the country's Gini coefficient was 58.8.[118]

Transportation

editDue to the large oil industry in the country, internationally recognized carriers flew to Malabo International Airport, which, in May 2014, had several direct connections to Europe and West Africa. There are three airports in Equatorial Guinea—Malabo International Airport, Bata Airport and the Annobón Airport on the island of Annobón. Malabo International Airport is the only international airport.

Every airline registered in Equatorial Guinea appears on the list of air carriers prohibited in the European Union (EU), which means that they are banned from operating services of any kind within the EU.[119] However, freight carriers provide service from European cities to the capital.[120]

Demographics

edit| Year | Million |

|---|---|

| 1950 | 0.2 |

| 2000 | 0.6 |

| 2020 | 1.4 |

The majority of the people of Equatorial Guinea are of Bantu origin.[124] The largest ethnic group, the Fang, is indigenous to the mainland, but substantial migration to Bioko Island since the 20th century means the Fang population exceeds that of the earlier Bubi inhabitants. The Fang constitute 80% of the population[125] and comprise around 67 clans. Those in the northern part of Río Muni speak Fang-Ntumu, while those in the south speak Fang-Okah; the two dialects have differences but are mutually intelligible. Dialects of Fang are also spoken in parts of neighboring Cameroon (Bulu) and Gabon. These dialects, while still intelligible, are more distinct. The Bubi, who constitute 15% of the population, are indigenous to Bioko Island. The traditional demarcation line between Fang and 'Beach' (inland) ethnic groups was the village of Niefang (limit of the Fang), east of Bata.

Coastal ethnic groups, sometimes referred to as Ndowe or "Playeros" (Beach People in Spanish): Combes, Bujebas, Balengues, and Bengas on the mainland and small islands, and Fernandinos, a Krio community on Bioko Island together comprise 5% of the population. Europeans (largely of Spanish or Portuguese descent, some with partial African ancestry) also live in the country, but most ethnic Spaniards left after independence.

A growing number of foreigners from neighboring Cameroon, Nigeria, and Gabon have immigrated to the country. According to the Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations (2002) 7% of Bioko islanders were Igbo, an ethnic group from southeastern Nigeria.[126] Equatorial Guinea received Asians and native Africans from other countries as workers on cocoa and coffee plantations. Other black Africans came from Liberia, Angola, and Mozambique. Most of the Asian population is Chinese, with small numbers of Indians.

Languages

editSince its independence in 1968, the main official language of Equatorial Guinea has been Spanish (the local variant is Equatoguinean Spanish), which acts as a lingua franca among its different ethnic groups. In 1970, during Macías' rule, Spanish was replaced by Fang, the language of its majority ethnic group, to which Macías belonged. That decision was reverted in 1979 after Macías' fall. Spanish remained as its lone official language until 1998, when French was added as its second one, as it had previously joined the Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (CEMAC), whose founding members are French-speaking nations, two of them (Cameroon and Gabon) surrounding its continental region.[127][3] Portuguese was adopted as its third official language in 2010.[128][129] Spanish has been an official language since 1844. It is still the language of education and administration. 67.6% of Equatorial Guineans can speak it, especially those living in the capital, Malabo.[130] French was only made official in order to join the Francophonie, and it is not locally spoken, except in some border towns.

Aboriginal languages are recognised as integral parts of the "national culture" (Constitutional Law No. 1/1998, 21 January). Indigenous languages (some of them creoles) include Fang, Bube, Benga, Ndowe, Balengue, Bujeba, Bissio, Gumu, Igbo, Pichinglis, Fa d'Ambô and the nearly extinct Baseke. Most African ethnic groups speak Bantu languages.[131]

Fa d'Ambô, a Portuguese creole, is in use in Annobón Province, in Malabo, and on Equatorial Guinea's mainland. Many residents of Bioko can also speak Spanish, particularly in the capital, and the local trade language, Pichinglis, an English-based creole. Spanish is not spoken much in Annobón. In government and education, Spanish is used. Noncreolized Portuguese is used as a liturgical language by local Catholics.[132] The Annobonese ethnic community tried to gain membership in the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP). The government financed an Instituto Internacional da Língua Portuguesa (IILP) sociolinguistic study in Annobón. It documented strong links with the Portuguese creole populations in São Tomé and Príncipe, Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau.[129]

Due to historical and cultural ties, in 2010, the legislature amended Article 4 of the Constitution of Equatorial Guinea to establish Portuguese as an official language of the Republic. This was an effort by the government to improve its communications, trade, and bilateral relations with Portuguese-speaking countries.[133][134][135] It also recognises long historical ties with Portugal and with Portuguese-speaking peoples of Brazil, São Tomé and Príncipe, and Cape Verde.

Some of the motivations for Equatorial Guinea's pursuit of membership in the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP) included access to several professional and academic exchange programmes and facilitated cross-border circulation of citizens.[130] The adoption of Portuguese as an official language was the primary requirement to apply for CPLP acceptance. In addition, the country was told it must adopt political reforms allowing effective democracy and respect for human rights.[136] The national parliament discussed this law in October 2011.[137]

In February 2012, Equatorial Guinea's foreign minister signed an agreement with the IILP on the promotion of Portuguese in the country.[138][139] In July 2012, the CPLP refused Equatorial Guinea full membership, primarily because of its continued serious violations of human rights. The government responded by legalising political parties, declaring a moratorium on the death penalty, and starting a dialog with all political factions.[129][140] Additionally, the IILP secured land from the government for the construction of Portuguese language cultural centres in Bata and Malabo.[129] At its tenth summit in Dili in July 2014, Equatorial Guinea was admitted as a CPLP member. Abolition of the death penalty and the promotion of Portuguese as an official language were preconditions of the approval.[141]

Religion

editThe principal religion in Equatorial Guinea is Christianity, the faith of 93% of the population. Roman Catholics make up the majority (88%), while a minority are Protestants (5%). Of the population, 2% follows Islam (mainly Sunni). The remaining 5% practise Animism, Baháʼí, and other beliefs,[142] and traditional animist beliefs are often mixed with Catholicism.[143]

Health

editEquatorial Guinea's malaria programs in the early 21st century achieved success in reducing malaria infection and mortality.[144] Their program consists of twice-yearly indoor residual spraying (IRS), the introduction of artemisinin combination treatment (ACTs), the use of intermittent preventive treatment in pregnant women (IPTp), and the introduction of long-lasting insecticide-treated mosquito nets (LLINs). Their efforts resulted in a reduction in all-cause under-five mortality from 152 to 55 deaths per 1,000 live births (down 64%), a drop that coincided with the launch of the program.[145]

In June 2014, four cases of polio were reported, making it the country's first outbreak of that disease.[146]

Education

editAmong sub-Saharan African countries, Equatorial Guinea has one of the highest literacy rates.[147] According to the Central Intelligence Agency's World Factbook, as of 2015[update], 95.3% of the population age 15 and over were able to read and write in the country.[147] Under Francisco Macias, few children received any type of education. Under President Obiang, the illiteracy rate dropped from 73% to 13%,[3] and the number of primary school students rose from 65,000 in 1986 to more than 100,000 in 1994. Education is free and compulsory for children between the ages of 6 and 14.[103]

The Equatorial Guinea government has partnered with Hess Corporation and The Academy for Educational Development (AED) to establish a $20 million education program for primary school teachers to teach modern child development techniques.[148] There are now 51 model schools whose active pedagogy will be a national reform.[needs update]

The country has one university, the Universidad Nacional de Guinea Ecuatorial (UNGE), with a campus in Malabo and a Faculty of Medicine located in Bata on the mainland. In 2009 the university produced the first 110 national doctors. The Bata Medical School is supported principally by the government of Cuba and staffed by Cuban medical educators and physicians.[149]

Culture

editIn June 1984, the First Hispanic-African Cultural Congress was convened to explore the cultural identity of Equatorial Guinea.[103]

Tourism

editAs of 2020[update], Equatorial Guinea has no UNESCO World Heritage Site or tentative sites for the World Heritage List.[150] The country also has no documented heritage listed in the Memory of the World Programme of UNESCO nor any intangible cultural heritage listed in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List.[151][152]

Tourist attractions are the colonial quarter in Malabo, the southern part of the island Bioko where you can hike to the Iladyi cascades and to remote beaches to watch nesting turtles, Bata with its shoreline Paseo Maritimo and the tower of liberty, Mongomo with its basilica (the second largest Catholic church in Africa) and the new planned and built capital Ciudad de la Paz.

Media and communications

editThe principal means of communication within Equatorial Guinea are three state-operated FM radio stations: the BBC World Service, Radio France Internationale and Gabon-based Africa No 1 broadcast on FM in Malabo. There is also an independent radio option called Radio Macuto; it is a web-based radio and news source known for publishing news that call out Obiang's regime. There are also five shortwave radio stations. Televisión de Guinea Ecuatorial, the television network, is state operated.[3][153] The international TV programme RTVGE is available via satellites in Africa, Europa, and the Americas and worldwide via Internet.[154] There are two newspapers and two magazines.

Equatorial Guinea ranks at position 161 out of 179 countries in the 2012 Reporters Without Borders press freedom index. The watchdog says the national broadcaster obeys the orders of the information ministry. Most of the media companies practice self-censorship, and are banned by law from criticising public figures. The state-owned media and the main private radio station are under the directorship of the president's son, Teodor Obiang.

Landline telephone penetration is low, with only two lines available per 100 people.[3] There is one GSM mobile telephone operator, with coverage of Malabo, Bata, and several mainland cities.[155][156] As of 2009[update], approximately 40% of the population subscribed to mobile telephone services.[3] The only telephone provider in Equatorial Guinea is Orange. According to World Bank, there were more than a million Internet users by 2022.[157]

Music

editPan-African styles like soukous and makossa are popular, as are reggaeton, Latin trap, reggae and rock and roll.

Cinema

editIn 2014, the South African-Dutch-Equatorial Guinean drama film Where the Road Runs Out was shot in the country. There is also the documentary The Writer from a Country Without Bookstores.[158] It is openly critical of Obiang's regime.

Sports

editEquatorial Guinea was chosen to co-host the 2012 African Cup of Nations in partnership with Gabon, and hosted the 2015 edition. The country was also chosen to host the 2008 Women's African Football Championship, which they won. The women's national team qualified for the 2011 World Cup in Germany. In June 2016, Equatorial Guinea was chosen to host the 12th African Games in 2019.

Equatorial Guinea is famous for the swimmers Eric Moussambani, nicknamed "Eric the Eel",[159] and Paula Barila Bolopa, "Paula the Crawler", who attended the 2000 Summer Olympics.[160]

Basketball has been increasing in popularity.[161]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ (Spanish: Guinea Ecuatorial [giˈnea ekwatoˈɾjal] ; French: Guinée équatoriale; Portuguese: Guiné Equatorial).

- ^ (Spanish: República de Guinea Ecuatorial, French: République de Guinée équatoriale, Portuguese: República da Guiné Equatorial), Local pronunciation:

- Spanish: República de Guinea Ecuatorial Spanish pronunciation: [reˈpuβlika ðe ɣiˈnea ekwatoˈɾjal]

- French: République de Guinée équatoriale [ʁepyblik d(ə) ɡine ekwatoʁjal]

- Portuguese: República da Guiné Equatorial Portuguese pronunciation: [ʁɛˈpuβlikɐ ðɐ ɣiˈnɛ ˌekwɐtuɾiˈal]

References

edit- ^ "History, language and culture in Equatorial Guinea". Archived from the original on 13 September 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea Adds Portuguese as the Country's Third Official Language". 14 October 2011. Archived from the original on 26 September 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Equatorial Guinea Archived 9 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Cia World Factbook.

- ^ "Religions in Equatorial Guinea | PEW-GRF". Global Religious Futures. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ "Section 3. Freedom to Participate in the Political Process". Equatorial Guinea 2020 Human Rights Report (PDF). U.S. Embassy in Equatorial Guinea (Report). 2020. p. 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ "Democracy Index 2020". Economist Intelligence Unit. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Equatorial Guinea". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (GQ)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Archived from the original on 27 October 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/2024" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ Appel, Hannah (13 December 2019). The Licit Life of Capitalism. Duke University Press. doi:10.1515/9781478004578. ISBN 978-1-4780-0457-8. S2CID 242248625.

- ^ GDP – per capita (PPP) – Country Comparison Archived 10 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Indexmundi.com. Retrieved on 5 May 2013.

- ^ GDP – per capita (PPP) Archived 24 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine, The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency.

- ^ "2019 Human Development Index Ranking | Human Development Reports". hdr.undp.org. Archived from the original on 23 May 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Mortality rate, under-5 (per 1,000 live births) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Equatorial Guinea profile". BBC. 21 March 2014. Archived from the original on 21 September 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ "OPEC: Equatorial Guinea". Archived from the original on 4 August 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ "Guiné Equatorial oficializa português – Portugal – DN". 19 August 2011. Archived from the original on 19 August 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2020 – via web.archive.org.

- ^ "Guinea Ecuatorial se convierte en el valedor del español en África". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 16 March 2016. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ "Gloria Nistal Rosique: El caso del español en Guinea ecuatorial, Instituto Cervantes" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ Worst of the Worst 2010. The World's Most Repressive Societies. freedomhouse.org

- ^ Equatorial Guinea – Reporters Without Borders Archived 15 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine. En.rsf.org. Retrieved on 5 May 2013.

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea". Trafficking in Persons Report 2020 Archived 17 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine. U.S. Department of State (16 June 2020). This source is in the public domain.

- ^ Bostoen (K.), Clist (B.), Doumenge (C.), Grollemund (R.), Hombert (J.-M.), Koni Muluwa (J.) & Maley (J.), 2015, Middle to Late Holocene Paleoclimatic Change and the Early Bantu Expansion in the Rain Forests of Western Central Africa, Current Anthropology, 56 (3), pp.354–384.

- ^ Clist (B.). 1990, Des derniers chasseurs aux premiers métallurgistes : sédentarisation et débuts de la métallurgie du fer (Cameroun, Gabon, Guinée-Equatoriale). In Lanfranchi (R.) & Schwartz (D.) éds. Paysages quaternaires de l'Afrique Centrale Atlantique. Paris : ORSTOM, Collection didactiques : 458–478

- ^ Clist (B.). 1998. Nouvelles données archéologiques sur l'histoire ancienne de la Guinée-Equatoriale. L'Anthropologie 102 (2) : 213–217

- ^ Sánchez-Elipe Lorente (M.). 2015. Las comunidades de la eda del hierro en África Centro-Occidental: cultura material e identidad, Tesi Doctoral, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid

- ^ Fegley, Randall (1989). Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy, p. 5. Peter Lang, New York. ISBN 0-8204-0977-4

- ^ Fegley, Randall (1989). Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy, p. 6. Peter Lang, New York. ISBN 0-8204-0977-4

- ^ a b Fegley, Randall (1989). Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy, p. 6–7. Peter Lang, New York. ISBN 0-8204-0977-4

- ^ "Fernando Po", Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911.

- ^ Fegley, Randall (1989). Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy, p. 7–8. Peter Lang, New York. ISBN 0-8204-0977-4

- ^ a b Fegley, Randall (1989). Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy, p. 13. Peter Lang, New York. ISBN 0-8204-0977-4

- ^ a b Fegley, Randall (1989). Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy, p. 9. Peter Lang, New York. ISBN 0-8204-0977-4

- ^ Fegley, Randall (1989). Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy, p. 8–9. Peter Lang, New York. ISBN 0-8204-0977-4

- ^ Clarence-Smith, William Gervase (2 September 2003). Cocoa and Chocolate, 1765-1914. Routledge. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-134-60778-5. Archived from the original on 23 February 2024. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- ^ Fegley, Randall (1989). Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy, p. 18. Peter Lang, New York. ISBN 0-8204-0977-4

- ^ a b c Clarence-Smith, William Gervase (1986) "Spanish Equatorial Guinea, 1898–1940" in The Cambridge History of Africa: From 1905 to 1940 Ed. J. D. Fage, A. D. Roberts, & Roland Anthony Oliver. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Archived 20 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Fegley, Randall (1989). Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy, p. 19. Peter Lang, New York. ISBN 0-8204-0977-4

- ^ Martino, Enrique (2012). "Clandestine Recruitment Networks in the Bight of Biafra: Fernando Pó's Answer to the Labour Question, 1926–1945". International Review of Social History. 57: 39–72. doi:10.1017/s0020859012000417. Archived from the original on 24 October 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ^ Roberts, A. D., ed. (1986). The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7. Cambridge University Press. p. 540.

- ^ Castillo-Rodríguez, S. (2012). "La última selva de España: Antropófagos, misioneros y guardias civiles. Crónica de la conquista de los Fang de la Guinea Española, 1914–1930". Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies. 13 (3): 315. doi:10.1080/14636204.2013.790703. S2CID 145077430.

- ^ Fegley, Randall (1989). Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy. New York: Peter Lang. pp. 20–21. ISBN 0-8204-0977-4.

- ^ Crowder, Michael, ed. (1984). The Cambridge History of Africa: Volume 8, from C. 1940 to C. 1975. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-22409-8.

- ^ Fegley, Randall (1989). Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy, pp. 59–60. Peter Lang, New York. ISBN 0-8204-0977-4

- ^ Fegley, Randall (1989). Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy, p. 51–52. Peter Lang, New York. ISBN 0-8204-0977-4

- ^ Fegley, Randall (1989). Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy, p. 55. Peter Lang, New York. ISBN 0-8204-0977-4

- ^ "Congratulations marking Independence Day continue to arrive" (Press release). Equatorial Guinea Press and Information Office. 10 September 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Campos, Alicia (2003). "The decolonization of Equatorial Guinea: the relevance of the international factor". Journal of African History. 44 (1): 95–116. doi:10.1017/s0021853702008319. hdl:10486/690991. S2CID 143108720. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ Fegley, Randall (1989). Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy, p. 60. Peter Lang, New York. ISBN 0-8204-0977-4

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea – Mass Atrocity Endings". Tufts University. 7 August 2015. Archived from the original on 10 September 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea – EG Justice". www.egjustice.org. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea's President Said to Be Retired, Not Ousted". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ a b Aworawo, David. "Decisive Thaw: The Changing Pattern of Relations between Nigeria and Equatorial Guinea, 1980–2005" (PDF). Journal of International and Global Studies. 1 (2): 103. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2013.

- ^ Sengupta, Kim (11 May 2007). "Coup plotter faces life in Africa's most notorious jail". London: News.independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on 29 December 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Daniels, Anthony (29 August 2004). "If you think this one's bad you should have seen his uncle". London: The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ^ "The Five Worst Leaders In Africa Archived 16 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine". Forbes. 9 February 2012.

- ^ "DC Meeting Set with President Obiang as Corruption Details Emerge". Global Witness. 15 June 2012. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ Forbes (5 March 2006) Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, President/Equatorial Guinea Archived 29 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Empresas portuguesas planeiam nova capital da Guiné Equatorial. africa21digital.com (5 November 2011).

- ^ Atelier luso desenha futura capital da Guiné Equatorial Archived 15 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Boasnoticias.pt (5 November 2011). Retrieved on 5 May 2013.

- ^ Arquitetos portugueses projetam nova capital para Guiné Equatorial Archived 10 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Piniweb.com.br. Retrieved on 5 May 2013.

- ^ Ateliê português desenha futura capital da Guiné Equatorial Archived 22 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Greensavers.pt (14 December 2011). Retrieved on 5 May 2013.

- ^ Simon, Allison (11 July 2014). "Equatorial Guinea: One man's fight against dictatorship". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ Lederer, Edith M. (2 June 2017). "Equatorial Guinea wins UN Security Council seat despite rights groups' concerns". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 16 January 2024. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ Bariyo, Nicholas (8 March 2021). "Equatorial Guinea Takes Stock After Giant Explosions". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Obiang obtiene el 99,7% de los votos en las elecciones de Guinea Ecuatorial entre denuncias de fraude masivo Archived 30 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine El País (21/11/2022)

- ^ Primeros resultados dan a Obiang casi el 100 % de votos en Guinea Ecuatorial Archived 22 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine Heraldo (21/11/2022)

- ^ BBC News – Equatorial Guinea country profile – Overview Archived 16 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Bbc.co.uk (11 December 2012). Retrieved on 5 May 2013.

- ^ Vines, Alex (9 July 2009). "Well Oiled". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 4 February 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- ^ Shaxson, Nicholas (17 March 2004). "Profile: Equatorial Guinea's great survivor". BBC News. Archived from the original on 12 June 2004. Retrieved 3 December 2004.

- ^ "Thatcher faces 15 years in prison". The Sydney Morning Herald. 27 August 2004. Archived from the original on 27 December 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ MacKay, Neil (29 August 2004). "The US knew, Spain knew, Britain knew. Whose coup was it?". Sunday Herald. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011.

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea, A trial with too many flaws". Amnesty International. 7 June 2005. Archived from the original on 12 February 2006.

- ^ "Presidential Decree". Republicofequatorialguinea.net. Archived from the original on 26 April 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Heather Layman, LPA (11 April 2006). "USAID and the Republic of Equatorial Guinea Agree to Unique Partnership for Development". Usaid.gov. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Organizational Reform & Institutional Capacity-Building. MPRI. Retrieved on 5 May 2013.

- ^ Equatorial Guinea | Amnesty International. Amnesty.org. Retrieved on 5 May 2013. Archived 1 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Equatorial Guinea | Human Rights Watch Archived 28 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Hrw.org. Retrieved on 5 May 2013.

- ^ Factoria Audiovisual S.R.L. "Declaración de la Unión Africana, sobre la supervisión de los comicios electorales – Página Oficial de la Oficina de Información y Prensa de Guinea Ecuatorial". Guineaecuatorialpress.com. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ "UPDATE 1-Tang renamed as Equatorial Guinea PM | News by Country". Af.reuters.com. 12 January 2010. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea country profile Archived 21 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine". BBC News. 8 May 2018.

- ^ Ignacio Milam Tang, new Vice President of the Nation Archived 25 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine. guineaecuatorialpress.com. 22 May 2012.

- ^ Interview with President Teodoro Obiang of Equatorial Guinea Archived 1 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. CNN. 5 October 2012.

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea targets opposition ahead of elections". Amnesty International. 15 May 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ "Convocatorial de Manifestacion, 25 de Junio 2013" (PDF). cpds-gq.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Opposition protest dispersed by security forces". country.eiu.com. Economist Intelligence Unit. 26 June 2013. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Freedom House. "Equatorial Guinea:Freedom in the World 2022". Freedom House. Archived from the original on 5 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ a b c "Equatorial Guinea, one dictatorship to the next". November 2021. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ "Corruption Perception Index (2020)". Transparency International. 2020. Archived from the original on 25 September 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea: Ignorance worth fistfuls of dollars". Freedom House. 13 June 2012. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ V-Dem Institute (2023). "The V-Dem Dataset". Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea (01/02)". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 12 September 2024.

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea (06/08)". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ "2024 Global Peace Index" (PDF).

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric [in German]; Olson, David; Joshi, Anup; et al. (5 April 2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545, Supplemental material 2 table S1b. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ Grantham, H. S.; Duncan, A.; Evans, T. D.; Jones, K. R.; Beyer, H. L.; Schuster, R.; Walston, J.; Ray, J. C.; Robinson, J. G.; Callow, M.; Clements, T.; Costa, H. M.; DeGemmis, A.; Elsen, P. R.; Ervin, J.; Franco, P.; Goldman, E.; Goetz, S.; Hansen, A.; Hofsvang, E.; Jantz, P.; Jupiter, S.; Kang, A.; Langhammer, P.; Laurance, W. F.; Lieberman, S.; Linkie, M.; Malhi, Y.; Maxwell, S.; Mendez, M.; Mittermeier, R.; Murray, N. J.; Possingham, H.; Radachowsky, J.; Saatchi, S.; Samper, C.; Silverman, J.; Shapiro, A.; Strassburg, B.; Stevens, T.; Stokes, E.; Taylor, R.; Tear, T.; Tizard, R.; Venter, O.; Visconti, P.; Wang, S.; Watson, J. E. M. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity – Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5978G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea – Plant and animal life". Encyclopedia Britannica. 29 November 2023. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ a b Law, Gwillim (22 March 2016). "Provinces of Equatorial Guinea". Statoids. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ "El Gobierno inicia sus actividades en Djibloho" (in Spanish). PDGE. 7 February 2017. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ "La Presidencia de la República sanciona dos nuevas leyes" (in Spanish). Equatorial Guinea Press and Information Office. 23 June 2017. Archived from the original on 25 June 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea government moves to new city in rainforest". BBC News. 8 February 2017. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ Law, Gwillim (22 April 2016). "Districts of Equatorial Guinea". Statoids. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ a b c "Equatorial Guinea". equatorialguinea.org. Archived from the original on 3 October 1999. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Justin Blum (7 September 2004). "U.S. Oil Firms Entwined in Equatorial Guinea Deals". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea grants two year extensions on oil & gas exploration". Reuters. 4 May 2020. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "Chevron, Equatorial Guinea sign production-sharing agreement for offshore block". Reuters. 10 December 2021. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "Inner City Press / Finance Watch: "Follow the Money, Watchdog the Regulators"". Inner City Press. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ "Overview". World Bank. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ Glenday, Craig (2013). Guinness Book of Records 2014. Guinness World Records Limited. p. [1]. ISBN 978-1-908843-15-9.

- ^ "OHADA.com: The business law portal in Africa". Archived from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 18 June 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ Equatorial Guinea | EITI Archived 13 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Eitransparency.org (27 September 2007). Retrieved on 5 May 2013.

- ^ "50 Things You Didn't Know About Africa" (PDF). World Bank. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ "The World Factbook: Equatorial Guinea". CIA. 16 April 2024. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ Hicks, Tyler (31 May 2011). "A Wealth Gap in Equatorial Guinea". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ "El franquismo resiste en algún lugar de África | PlayGround". Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea Economic Outlook". African Development Bank. 29 March 2019. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ "Guinea". World Economics. Archived from the original on 12 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ List of banned EU air carriers Archived 4 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Ec.europa.eu. Retrieved on 5 May 2013.

- ^ (source?)

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX) ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "UNData app: Ecuatorial Guinea population 2020". UN Data. Archived from the original on 11 August 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ Vines, Alex (2009). Well Oiled: Oil and Human Rights in Equatorial Guinea. Human Rights Watch. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-56432-516-7. Archived from the original on 16 February 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea's God". BBC. 26 July 2003. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ^ Minahan, James (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: A-C. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 330. ISBN 0-313-32109-4.

- ^ "5. Guinea Ecuatorial - Centro Virtual Cervantes" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ "Guiné Equatorial" (in Portuguese). CPLP. Archived from the original on 27 November 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Formação de professores e programas televisivos introduzem português na Guiné-Equatorial" [Teacher formation and television programs introduce Portuguese in Equatorial Guinea] (in Portuguese). Sol. 5 February 2014. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ a b Obiang convierte al portugués en tercer idioma oficial para entrar en la Comunidad lusófona de Naciones, Terra. 13 July 2007

- ^ Oficina de Información y Prensa de Guinea Ecuatorial, Ministerio de Información, Cultura y Turismo Archived 9 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Guineaecuatorialpress.com. Retrieved on 5 May 2013.

- ^ "Fa d'Ambu". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2010.

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea Adds Portuguese as the Country's Third Official Language". PRNewsWire. 14 October 2011. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 15 November 2010.

- ^ "El portugués será el tercer idioma oficial de la República de Guinea Ecuatorial" (in Spanish). Gobierno de la Republica de Guinea Ecuatoria. Archived from the original on 3 September 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2010.

- ^ "Proyecto de Ley Constitucional" (PDF). Gobierno de la Republica de Guinea Ecuatorial. 14 October 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 January 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2010.

- ^ "Portuguese will be the third official language of the Republic of Equatorial Guinea" Archived 4 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Guinea Ecuatorial Press, (20 July 2010). Retrieved on 5 May 2013.

- ^ María Jesús Nsang Nguema (Prensa Presidencial) (15 October 2011). "S. E. Obiang Nguema Mbasogo clausura el Segundo Periodo Ordinario de Sesiones del pleno de la Cámara de Representantes del Pueblo" [President Obiang closes second session period of parliament] (in Spanish). Oficina de Información y Prensa de Guinea Ecuatorial (D. G. Base Internet). Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ "Assinado termo de cooperação entre IILP e Guiné Equatorial" [Protocol signed on cooperation between IILP and Guinea Equatorial] (in Portuguese). Instituto Internacional de Língua Portuguesa. 7 February 2012. Archived from the original on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ "Protocolo de Cooperação entre a Guiné-Equatorial e o IILP" [Protocol on cooperation between IILP and Guinea Equatorial] (in Portuguese). CPLP. 7 February 2012. Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012. This note contains a link to the text of the protocol in PDF format.

- ^ "CPLP vai ajudar Guiné-Equatorial a "assimilar valores"" (in Portuguese). Expresso. 20 September 2014. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ "Nota informativa: Missão da CPLP à Guiné Equatorial" (in Portuguese). CPLP. 3 May 2011. Archived from the original on 12 December 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report for 2017". Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ Matt, Phillips; Andrew, David; Bainbridge, James; Bewer, Tim; Bindloss, Joe; Carillet, Jean-Bernard; Clammer, Paul; Cornwell, Jane; Crossan, Rob (September 2007). Matt Phillips (ed.). The Africa Book: A Journey Through Every Country in the Continent. Footscray, Australia: Lonely Planet. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-74104-602-1. OCLC 144596621.

- ^ Steketee, R. W. (2009). "Good news in malaria control... Now what?". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 80 (6): 879–880. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2009.80.879. PMID 19478241.

- ^ Marked Increase in Child Survival after Four Years of Intensive Malaria Control Archived 10 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Ajtmh.org. Retrieved on 5 May 2013.

- ^ "Detection of poliovirus in São Paulo airport sewage: WHO". Brazil News.Net. Archived from the original on 10 July 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Literacy - The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ HESS and AED Partner to Improve Education in Equatorial Guinea. AED.org

- ^ Equatorial Guinea Minister Seeks Strong Ties With U.S Archived 11 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Voanews.com (4 April 2010). Retrieved on 5 May 2013.

- ^ Tentative Lists Archived 15 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine. unesco.org

- ^ Equatorial Guinea – intangible heritage – Culture Sector Archived 19 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine. UNESCO. Retrieved on 19 January 2017.

- ^ Memory of the World | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Archived 25 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Unesco.org. Retrieved on 19 January 2017.

- ^ "Country Profile: Equatorial Guinea: Media". BBC News. 26 January 2008. Archived from the original on 6 April 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- ^ "TVGE Internacional". LyngSat. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ "GSMWorld Providers: Equatorial Guinea". GSM World. 2008. Archived from the original on 14 April 2008.

- ^ "GSMWorld GETESA Coverage Map". GSM World. 2008. Archived from the original on 8 January 2009.

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea". World Bank Open Data. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ "The Writer from a Country Without Bookstores". elescritordeunpais.com. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ O'Mahony, Jennifer (27 July 2012). "London 2012 Olympics: how Eric 'the Eel' Moussambani inspired a generation in swimming pool at Sydney Games". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 April 2005. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ "'Paula the Crawler' sets record". BBC News. 22 September 2000. Archived from the original on 27 June 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Scafidi, Oscar (1 November 2015). Equatorial Guinea. Bradt Travel Guides Ltd. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-78477-136-2. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

Sources

edit- D. L. Claret. Cien años de evangelización en Guinea Ecuatorial (1883–1983) / One Hundred Years of Evangelism in Equatorial Guinea (1983, Barcelona: Claretian Missionaries).

- Robert Klitgaard. 1990. Tropical Gangsters. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-08760-4. A World Bank economist tries to assist pre-oil Equatorial Guinea.