Natives of the Arabian Peninsula, many Qataris (Arabic: قطريون) are descended from a number of migratory Arab tribes that came to Qatar in the 18th century from mainly the neighboring areas of Nejd and Al-Hasa. Some are descended from Omani tribes. Qatar has about 2.6 million inhabitants as of early 2017, the vast majority of whom (about 92%) live in Doha, the capital.[1] Foreign workers amount to around 88% of the population, the largest of which comprise South Asians, with those from India alone estimated to be around 700,000.[2] Egyptians and Filipinos are the largest non-South Asian migrant group in Qatar. The treatment of these foreign workers has been heavily criticized with conditions suggested to be modern slavery. However the International Labour Organization published report in November 2022 that contained multiple reforms by Qatar for its migrant workers. The reforms included the establishment of the minimum wage, wage protection regulations, improved access for workers to justice, etc. It included data from last 4 years of progress in workers conditions of Qatar. The report also revealed that the freedom to change jobs was initiated, implementation of Occupational safety and health & labor inspection, and also the required effort from the nation's side.[3]

| Demographics of Qatar | |

|---|---|

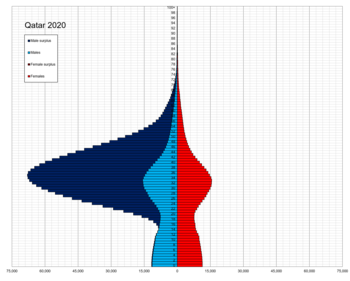

Population pyramid of Qatar in 2022 | |

| Population | 2,937,800 (2022 est.) |

| Growth rate | 1.04% (2022 est.) |

| Birth rate | 9.33 births/1,000 population (2022 est.) |

| Death rate | 1.42 deaths/1,000 population (2022 est.) |

| Life expectancy | 79.81 years |

| • male | 77.7 years |

| • female | 81.96 years (2022 est.) |

| Fertility rate | 1.9 children born/woman (2022 est.) |

| Infant mortality rate | 6.62 deaths/1,000 live births |

| Net migration rate | 2.45 migrant(s)/1,000 population (2022 est.) |

| Age structure | |

| 0–14 years | 14.23% |

| 15–64 years | 84.61% |

| 65 and over | 1.16% |

| Sex ratio | |

| Total | 3.36 male(s)/female (2022 est.) |

| At birth | 1.02 male(s)/female |

| Under 15 | 1.02 male(s)/female |

| 65 and over | 1.13 male(s)/female |

| Nationality | |

| Nationality | Qatari |

| Language | |

| Official | Arabic |

Islam is the official religion, and Islamic jurisprudence is the basis of Qatar's legal system. A significant minority religion is Hindu due to the large number of Qatar's migrant workers coming from India.

Arabic is the official language and English is the lingua franca of business. Hindi-Urdu and Malayalam are among the most widely spoken languages by the foreign workers.[4] Education in Qatar is compulsory and free for all citizens 6–16 years old. The country has an increasingly high literacy rate.

Population

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1986 | 369,079 | — |

| 1997 | 522,023 | +3.20% |

| 2004 | 744,029 | +5.19% |

| 2010 | 1,699,435 | +14.76% |

| 2015 | 2,404,776 | +7.19% |

| 2020 | 2,846,118 | +3.43% |

| 2023 | 3,063,005 | +2.48% |

| Source: Qatar Statistics Authority[5][6] | ||

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 25,000 | — |

| 1960 | 47,000 | +6.52% |

| 1970 | 108,000 | +8.68% |

| 1980 | 222,000 | +7.47% |

| 1990 | 474,000 | +7.88% |

| 2000 | 591,000 | +2.23% |

| 2010 | 1,759,000 | +11.52% |

| Source: United Nations[7] | ||

Foreigners

editForeigners constitute 85% to 90% of Qatar's population of 2.7 million, with migrant workers making up approximately 95% of the workforce.[8] South Asia and Southeast Asia are the primary regions which migrants come from. Societal divisions exist depending on the origin of the foreigner, with Europeans, North Americans, and Arabs typically securing better job opportunities and social privileges than sub-Saharan Africans and South Asians.[9] Socialization between foreigners and Qataris is slightly limited due to language barriers and vastly different religious and cultural customs.[10]

The human rights of migrant workers is limited by the country's Kafala system, which stipulates their requirement of a Qatari sponsor and regulates their entry and exit.[11] Prospective migrant workers from origin countries sometimes face exorbitant recruitment fees, surpassing government-set limits, paid to licensed and unlicensed recruitment entities. These charges, ranging from $600 to $5,000, often force workers into debt and compel them to sell family assets. Government-to-government agreements have emerged in recent years to mitigate opaque recruitment practices and worker exploitation. Many companies in Qatar skirt local laws, resulting in workers facing delayed or non-payment of wages. While some employers deposit wages into bank accounts, most workers are paid in cash without detailed pay slips, hindering evidence of payment and complicating remittances. Additionally, the confiscation of passports by employers is a common practice in Qatar which limits the workers' freedom of movement and exposes them to potential exploitation.[12]

By nationality

editA 2011–2014 report by the International Organization for Migration recorded 176,748 Nepali Citizens living in Qatar as migrant workers.[13][14][15] In 2012 about 7,000 Turkish nationals lived in Qatar[16] and in 2016 about 1,000 Colombian nationals and descendants lived in Qatar. No official numbers are published of the foreign population broken down by nationality, however a firm provided estimates as of 2019:[17]

| Country | Number | percent |

|---|---|---|

| India | 700,000 | |

| Qatar | 600,000 | |

| Bangladesh | 400,000 | |

| Nepal | 400,000 | |

| Egypt | 300,000 | |

| Philippines | 236,000 | |

| Pakistan | 180,000 | |

| Sri Lanka | 140,000 | |

| Sudan | 60,000 | |

| Syria | 54,000 | |

| Jordan | 51,000 | |

| Lebanon | 40,000 | |

| United States | 40,000 | |

| Kenya | 30,000 | |

| Iran | 30,000 |

Vital statistics

editUN estimates

edit| Period | Live births per year | Deaths per year | Natural change per year | CBR* | CDR* | NC* | TFR* | IMR* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950–1955 | 1,000 | 0 | 1,000 | 47.5 | 13.8 | 33.7 | 6.97 | 126 |

| 1955–1960 | 2,000 | 0 | 1,000 | 44.3 | 11.3 | 33.0 | 6.97 | 110 |

| 1960–1965 | 2,000 | 1,000 | 2,000 | 41.0 | 8.8 | 32.1 | 6.97 | 90 |

| 1965–1970 | 4,000 | 1,000 | 3,000 | 38.6 | 6.8 | 31.8 | 6.97 | 71 |

| 1970–1975 | 5,000 | 1,000 | 4,000 | 34.8 | 5.2 | 29.6 | 6.77 | 53 |

| 1975–1980 | 7,000 | 1,000 | 6,000 | 35.7 | 4.0 | 31.7 | 6.11 | 38 |

| 1980–1985 | 10,000 | 1,000 | 9,000 | 33.2 | 3.1 | 30.1 | 5.45 | 28 |

| 1985–1990 | 11,000 | 1,000 | 10,000 | 25.4 | 2.5 | 22.9 | 4.50 | 23 |

| 1990–1995 | 11,000 | 1,000 | 10,000 | 22.8 | 2.2 | 20.6 | 4.01 | 18 |

| 1995–2000 | 10,000 | 1,000 | 9,000 | 19.2 | 2.1 | 17.1 | 3.30 | 14 |

| 2000–2005 | 13,000 | 1,000 | 12,000 | 18.8 | 1.9 | 16.9 | 3.01 | 11 |

| 2005–2010 | 18,000 | 2,000 | 16,000 | 14.1 | 1.6 | 12.5 | 2.40 | 9 |

| * CBR = crude birth rate (per 1000); CDR = crude death rate (per 1000); NC = natural change (per 1000); IMR = infant mortality rate per 1000 births; TFR = total fertility rate (number of children per woman) | ||||||||

| Source:[18] | ||||||||

Registered births and deaths

edit| Average population | Live births | Deaths | Natural change | Crude birth rate (per 1000) | Crude death rate (per 2) | Natural change (per 1000) | TFR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 108,000 | 3,616 | 464 | 3,152 | 33.4 | 4.3 | 29.1 | |

| 1971 | 118,000 | 3,921 | 491 | 3,430 | 33.2 | 4.2 | 29.0 | |

| 1972 | 129,000 | 4,038 | 563 | 3,475 | 31.2 | 4.4 | 26.8 | |

| 1973 | 141,000 | 4,367 | 660 | 3,707 | 31.0 | 4.7 | 26.3 | |

| 1974 | 152,000 | 4,562 | 688 | 3,874 | 30.0 | 4.5 | 25.5 | |

| 1975 | 163,000 | 4,559 | 600 | 3,959 | 28.0 | 3.7 | 24.3 | |

| 1976 | 172,000 | 4,893 | 609 | 4,284 | 28.4 | 3.5 | 24.9 | |

| 1977 | 181,000 | 5,313 | 686 | 4,627 | 29.4 | 3.8 | 25.6 | |

| 1978 | 190,000 | 5,977 | 645 | 5,332 | 31.4 | 3.4 | 28.0 | |

| 1979 | 203,000 | 6,057 | 709 | 5,348 | 29.8 | 3.5 | 26.3 | |

| 1980 | 222,000 | 6,750 | 662 | 6,088 | 30.5 | 3.0 | 27.5 | |

| 1981 | 246,000 | 7,192 | 725 | 6,467 | 29.3 | 3.0 | 26.3 | |

| 1982 | 275,000 | 8,032 | 789 | 7,243 | 29.2 | 2.9 | 26.3 | |

| 1983 | 307,000 | 8,261 | 803 | 7,458 | 26.9 | 2.6 | 24.3 | |

| 1984 | 338,000 | 8,613 | 642 | 7,971 | 25.5 | 1.9 | 23.6 | |

| 1985 | 368,000 | 9,225 | 794 | 8,431 | 25.1 | 2.2 | 22.9 | |

| 1986 | 395,000 | 9,942 | 784 | 9,158 | 25.2 | 2.0 | 23.2 | |

| 1987 | 420,000 | 9,919 | 788 | 9,131 | 23.6 | 1.9 | 21.7 | |

| 1988 | 442,000 | 10,842 | 861 | 9,981 | 24.5 | 1.9 | 22.6 | |

| 1989 | 460,000 | 10,908 | 847 | 10,061 | 23.7 | 1.8 | 21.9 | |

| 1990 | 474,000 | 11,022 | 871 | 10,151 | 23.3 | 1.8 | 21.5 | |

| 1991 | 483,000 | 9,756 | 883 | 8,873 | 20.2 | 1.8 | 18.4 | |

| 1992 | 488,000 | 10,459 | 944 | 9,515 | 21.4 | 1.9 | 19.5 | |

| 1993 | 491,000 | 10,822 | 913 | 9,909 | 22.0 | 1.9 | 20.1 | |

| 1994 | 495,000 | 10,561 | 964 | 9,597 | 21.3 | 1.9 | 19.4 | |

| 1995 | 501,000 | 10,371 | 1,000 | 9,371 | 20.7 | 2.0 | 18.7 | |

| 1996 | 512,000 | 10,317 | 1,015 | 9,302 | 20.1 | 2.0 | 18.1 | |

| 1997 | 529,000 | 10,447 | 1,060 | 9,387 | 19.8 | 2.0 | 17.8 | |

| 1998 | 549,000 | 10,781 | 1,157 | 9,624 | 19.6 | 2.1 | 17.5 | |

| 1999 | 570,000 | 10,846 | 1,148 | 9,698 | 19.0 | 2.0 | 17.0 | |

| 2000 | 591,000 | 11,438 | 1,173 | 10,265 | 19.4 | 2.0 | 17.4 | |

| 2001 | 608,000 | 12,355 | 1,210 | 11,145 | 20.3 | 2.0 | 18.3 | |

| 2002 | 624,000 | 12,388 | 1,220 | 11,168 | 19.8 | 2.0 | 17.8 | |

| 2003 | 654,000 | 13,026 | 1,311 | 11,715 | 19.9 | 2.0 | 17.9 | |

| 2004 | 715,000 | 13,589 | 1,341 | 12,248 | 19.0 | 1.9 | 17.1 | 2.78 |

| 2005 | 821,000 | 13,514 | 1,545 | 11,969 | 16.5 | 1.9 | 14.6 | 2.62 |

| 2006 | 978,000 | 14,204 | 1,750 | 12,454 | 14.5 | 1.8 | 12.7 | 2.48 |

| 2007 | 1,178,000 | 15,695 | 1,776 | 13,919 | 13.3 | 1.5 | 11.8 | 2.45 |

| 2008 | 1,448,000 | 17,480 | 1,942 | 15,538 | 12.1 | 1.3 | 10.8 | 2.43 |

| 2009 | 1,639,000 | 18,351 | 2,008 | 16,343 | 11.2 | 1.2 | 10.0 | 2.28 |

| 2010 | 1,715,000 | 19,504 | 1,970 | 17,534 | 11.4 | 1.1 | 10.3 | 2.08 |

| 2011 | 1,733,000 | 20,623 | 1,949 | 18,674 | 12.0 | 1.1 | 10.9 | 2.12 |

| 2012 | 1,833,000 | 21,423 | 2,031 | 19,392 | 11.7 | 1.1 | 10.6 | 2.05 |

| 2013 | 2,004,000 | 23,708 | 2,133 | 21,575 | 11.8 | 1.1 | 10.7 | 2.00 |

| 2014 | 2,216,000 | 25,443 | 2,366 | 23,007 | 11.5 | 1.1 | 10.4 | 2.00 |

| 2015 | 2,438,000 | 26,622 | 2,317 | 24,305 | 10.9 | 1.0 | 9.9 | 2.00 |

| 2016 | 2,618,000 | 26,816 | 2,347 | 24,469 | 10.2 | 0.9 | 9.3 | 1.85 |

| 2017 | 2,725,000 | 27,906 | 2,294 | 25,612 | 10.2 | 0.8 | 9.4 | 1.83 |

| 2018 | 2,760,000 | 28,069 | 2,385 | 25,684 | 10.2 | 0.9 | 9.3 | 1.75 |

| 2019 | 2,799,000 | 28,412 | 2,200 | 26,212 | 10.2 | 0.8 | 9.4 | 1.73 |

| 2020 | 2,834,000 | 29,014 | 2,811 | 26,203 | 10.2 | 1.0 | 9.2 | 1.67 |

| 2021 | 2,748,000 | 26,319 | 2,841 | 23,478 | 9.6 | 1.0 | 8.5 | 1.60 |

| 2022 | 2,932,000 | 26,316 | 2,792 | 23,524 | 9.0 | 1.0 | 8.0 | 1.51 |

| 2023 | 3,063,000 | 27,414 | 2,651 | 24,763 | 9.0 | 0.9 | 8.1 | |

| Sources:[19][20] | ||||||||

Population Estimates by Sex and Age Group (01.VII.2019):[21]

| Age Group | Male | Female | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2 064 276 | 734 926 | 2 799 202 | |

| 0–4 | 74 902 | 71 724 | 146 626 | |

| 5–9 | 71 614 | 69 267 | 140 881 | |

| 10–14 | 56 637 | 54 291 | 110 928 | |

| 15–19 | 47 897 | 38 313 | 86 210 | |

| 20–24 | 205 862 | 44 382 | 250 244 | |

| 25–29 | 352 616 | 92 515 | 445 131 | |

| 30–34 | 393 644 | 109 435 | 503 079 | |

| 35–39 | 319 713 | 89 034 | 408 747 | |

| 40–44 | 211 372 | 62 490 | 273 862 | |

| 45–49 | 145 216 | 39 577 | 184 793 | |

| 50–54 | 86 415 | 25 298 | 111 713 | |

| 55–59 | 51 306 | 16 530 | 67 836 | |

| 60–64 | 26 902 | 9 875 | 36 777 | |

| 65–69 | 10 744 | 5 365 | 16 109 | |

| 70–74 | 4 905 | 3 154 | 8 059 | |

| 75–79 | 2 703 | 2 031 | 4 734 | |

| 80+ | 1 828 | 1 645 | 3 473 | |

| Age group | Male | Female | Total | Percent |

| 0–14 | 203 153 | 195 282 | 398 435 | |

| 15–64 | 1 840 943 | 527 449 | 2 368 392 | |

| 65+ | 20 180 | 12 195 | 32 375 |

Life expectancy

edit| Period | Life expectancy in Years |

Period | Life expectancy in Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950–1955 | 55.2 | 1985–1990 | 74.5 |

| 1955–1960 | 59.2 | 1990–1995 | 75.3 |

| 1960–1965 | 62.9 | 1995–2000 | 76.0 |

| 1965–1970 | 66.6 | 2000–2005 | 76.6 |

| 1970–1975 | 69.7 | 2005–2010 | 76.9 |

| 1975–1980 | 71.8 | 2010–2015 | 77.6 |

| 1980–1985 | 73.4 | ||

| Source: UN World Population Prospects[22] | |||

Qatari people

editNative Qataris can be divided into three ethnic groups: Bedouin Arabs, hadar, and Afro-Arab, which can be considered a sub-category of the hadar. Some of the hadar are of Iranian descent.[23] Qatari citizens comprise 11.6% of the country's population.

Citizenship

editTwo distinctions exist between Qatari citizens: those whose families migrated to Qatar before 1930, commonly referred to as "native Qataris", and those whose families arrived after. Previously, the 1961 citizenship law defined Qatari citizens as only those families who have been in the country since the 1930s,[24] though this was repealed in the 2005 citizenship law. In 2021, a law was signed by Emir Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani restricting the rights to vote in local elections for those whose families' arrival post-date the 1930s, leading to minor demonstrations and public disapproval. This led Al Thani to later announce that he would amend the law to allow all citizens to vote in future elections.[25]

Children of Qatari mothers and foreign fathers are not granted Qatari citizenship; however, as of 2018, they are granted permanent residency status, which entitles them to similar state benefits as Qatari citizens. Nonetheless, the government limits the number of permanency residency visas it issues each year.[26] The 2005 citizenship law allows for revocation of citizenship without appeal, which has been used on a number of families with dual citizenship.[27]

Ethnic groups

editQatar's population has been historically diverse due to its role as a trading center, a refuge for nomadic tribes, and a hub for the pearling industry. Ethnic groups and the differences among them are considered sensitive topics in Qatari society and are rarely discussed in official contexts.[24]

Bedouins, though constituting approximately 10 percent of the population, hold an outsized role in local culture. Many Qataris descend from tribes that migrated from Najd and Al-Hasa in the 18th century. Commonly called the bedu, they maintain ties, homes, and even passports in Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states. In the early 20th century, bedu migrated from the Arabian interior, with some traveling intermittently between Qatar and Bahrain. During the mid-20th century economic boom, many found work in the oil industry, police, army, and security services. The government settled Bedu families in the 1960s, discouraging the nomadic lifestyle. Today, many live in urban areas but return to the desert to stay connected to their roots. Many Bedu see themselves as noble and "pure" Arabs, often looking down on the settled population (hadar) as influenced by urban and Persian elements. Intermarriage between these groups is rare.[24]

The hadar, a diverse group of settled Qatari citizens, includes Baharna, Huwala, Ajam (Iranians), and Afro-Arabs. Baharna Arabs, a group native to Qatar and often practicing Shia Muslims, sometimes face discrimination from the Sunni majority. Huwala Arabs, who are Sunni Muslims, migrated through the Persian Gulf to Persia and back to Qatar. Historically wealthier and better educated due to trade and pearling, their advantage has diminished as education became more accessible. The Ajam, ethnic Shia Persians, were active in boat building and still speak Farsi. Qatar’s Afro-Arab population descends from slaves brought from East Africa for the pearling industry. While some Arabs may view this group as "less" Qatari, most consider them full citizens. Despite occasional tensions, these groups are well integrated into Qatari society. Intermarriage is increasing, and Persian and African influences are evident in local culture.[24]

Religions

editQatar is an Islamic state with multi-religious minorities like most of the Persian Gulf countries with waves of migration over the last 30 years. The official state religion is Sunni Islam. The community is made up of Sunni and Shi’a Muslims, Christians, Hindus, and small groups of Buddhists and Baha’is.[28] Muslims form 65.5% of the Qatari population, followed by Christians at 15.4%, Hindus at 14.2%, Buddhists at 3.3% and the rest 1.9% of the population follow other religions or are unaffiliated. Qatar is also home to numerous other religions mostly from the Middle East and Asia.[29]

Languages

editArabic

editArabic is the official language of Qatar according to Article 1 of the Constitution.[30] Arabic in Qatar not only serves as a symbol of national identity but is also the medium of official communication, legislation, and education. The government has instituted policies to reinforce the use of Arabic, including the Arabic Language Protection Law enacted in 2019, which mandates the use of Arabic in governmental and public functions and penalizes non-compliance. Arabic speakers constitute a minority of the 2.8 million population, at around 11%.[31]

Qatari Arabic, a dialect of Gulf Arabic, is the primary dialect spoken. As the prestige dialect within the nation, Qatari Arabic not only functions in everyday communication but also plays a significant role in maintaining cultural identity and social cohesion among the Qatari people. The vocabulary of Qatari Arabic incorporates a plethora of loanwords from Aramaic, Persian, Turkish, and more recently, English. Phonetically, it conserves many classical Arabic features such as emphatic consonants and interdental sounds, which distinguish it from other Arabic dialects that have simplified these elements. Syntactically, Qatari Arabic exhibits structures that align with other Gulf dialects but with unique adaptations, such as specific verb forms and negation patterns.[32]

In Qatari Arabic, like many Arabic dialects, there is a significant phonological distinction between long and short vowels. This distinction is crucial for both pronunciation and meaning. Long vowels in Qatari Arabic are generally held for approximately twice the duration of their short counterparts. This length distinction can affect the meaning of words, making vowel length phonemically significant. Qatari Arabic typically includes five long vowels: /ā/, /ē/, /ī/, /ō/, and /ū/. These long vowels are analogous to the long vowels found in Classical Arabic and are integral to maintaining the clarity and meaning of words. For example, the word for 'dog' in Arabic is /kalb/ with a short vowel, but with a long vowel, it becomes /kālib/, meaning 'heart'. Short vowels in Qatari Arabic are /a/, /i/, and /u/. These vowels are shorter in duration and can be less emphasized in casual speech. In some dialectical variations, short vowels may even be dropped entirely in certain environments, a process known as vowel reduction. This feature is common in rapid, informal speech and can lead to significant variations in pronunciation from the standard forms of the language. The distinction between long and short vowels in Qatari Arabic not only affects pronunciation but also plays a role in the grammatical structure of words, influencing verb conjugations, noun cases, and the definiteness of nouns through the use of the definite article /al-/.[32]

As English is considered the prestige lingua franca in Qatar, bilingual locals have incorporated elements of English into Qatari Arabic when communicating on an informal level. This mixture of English terms and phrases in Qatari Arabic speech is colloquially known as Qatarese.[33] The practice of interchanging English and Arabic words is known as code-switching and is mostly seen in urban areas and among the younger generation.[32]

As a result of mass migration, a South Asian pidgin form of Qatari Arabic has emerged in modern times.[32]

English

editEnglish is the de facto second language of Qatar, and is very commonly used in business. Because of Qatar's varied ethnic landscape, English has been recognized as the most convenient medium for people of different backgrounds to communicate with each other.[34] The history of English use in the country dates back to the mid-19th and early 20th centuries when the British Empire would frequently draft treaties and agreements with the emirates of the Persian Gulf. One such treaty was the 1916 protectorate treaty signed between Abdullah bin Jassim Al Thani and the British representative Percy Cox, under which Qatar would be placed under British administration in exchange for protection. Another agreement drafted in English came in 1932 and was signed between the Qatarian government and the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. These agreements were mainly facilitated by foreign interpreters due to neither party possessing the required language skills for such complex arrangements. For instance, a translator and native Arabic speaker named A. A. Hilmy interpreted the 1932 agreement for Qatar.[35]

French

editDespite Qatar's population comprising only 1% French speakers, the country was admitted to the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie as an associate member in 2012. It was not required to join as an observer state prior to its full admittance.[36]

Other languages

editQatar's linguistic diversity is significantly shaped by its large expatriate population from South Asia and Southeast Asia. The most common Asian languages among migrants are Hindi, Urdu, Tagalog, Bengali, Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam. Hindi and Malayalam are particularly prevalent, with large communities of speakers from India. For example, Malayalam is spoken by a significant portion of the Indian community originating from the southern state of Kerala, who make up the majority of the country's Indian diaspora. Similarly, the widespread presence of languages such as Bengali, Tamil, and Urdu is attributed to a large portion of expatriates from Bangladesh, Pakistan, and other parts of India.[31]

In 2015, there were more newspapers printed by the government in Malayalam than in Arabic or English.[37]

During the COVID-19 pandemic in Qatar, the importance of these languages was particularly recognized in public health communications. The Qatari government utilized Asian languages extensively in its awareness campaigns to ensure that critical health information reached all population segments, including those who might not speak Arabic or English proficiently. This multilingual approach involved disseminating information through various channels such as radio, printed pamphlets, and digital media.[31]

References

edit- ^ "Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics". Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ "Population of Qatar by nationality – 2017 report". Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ "Four years of labour reforms in Qatar". www.ilo.org. 1 November 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Qatar Tourist Guide". Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ^ "Qatar Planning and Statistics Authority – Monthly Figures on Total Population".

- ^ "Qatar Statistics Authority – Population 2012" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ^ World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision Archived February 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Qatar". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ Pattison, Pete (19 December 2022). "This World Cup should be remembered for its racism. But Qatar is not the victim". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ Camacho, Beatriz. "Culture and social etiquette in Qatar". Expatica. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ "World Report 2020: Qatar". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ Jureidini, Ray (2014). "Executive Summary and Recommendations". Migrant Labour Recruitment to Qatar (PDF). Qatar Foundation. ISBN 978-9927-101-75-5.

- ^ "Nepalese Migrant workers in Qatar from Terai". Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ "Iom International Report claims half of Nepalese migrant workers in foreign are Madhesi people from Terai, mainly to Qatar, Malaysia, UAE, Saudi Arabia and UAE". Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ "Half of madhesi people of Terai are in Qatar".

- ^ "Turkish school in Qatar to help spread Turkish culture" (Archive). Today's Zaman. Wednesday February 29, 2012. Retrieved on September 26, 2015.

- ^ "Population of Qatar by nationality in 2019". Priya DSouza Communications. 15 August 2019. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision Archived May 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [1] United nations. Demographic Yearbooks

- ^ "Domains". Archived from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2015. Qatar Information Exchange]

- ^ "UNSD — Demographic and Social Statistics".

- ^ "World Population Prospects – Population Division – United Nations". Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ Carol R. Ember and Melvin Ember (2001). Countries and Their Cultures. Macmillan Reference USA. p. 1825. ISBN 9780028649498.

- ^ a b c d "Qatar Cultural Field Guide" (PDF). Quantico, Virginia: United States Marine Corps. August 2010. p. 21–24. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ "Qatar: Freedom in the World Country Report". Freedom House. 2024. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ "Qatar: Submission to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child". Human Rights Watch. 15 February 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "Qatar: Families Arbitrarily Stripped of Citizenship". Freedom House. 12 May 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ "Qatar". rpl.hds.harvard.edu. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- ^ "Religious Composition by Country" (PDF). Global Religious Landscape. Pew Forum. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ "Qatar's Constitution of 2003" (PDF). Constitute Project. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Rizwan, Ahmad; Hillman, Sara (30 November 2020). "Laboring to communicate: Use of migrant languages in COVID-19 awareness campaign in Qatar". Multilingua. 40 (5). De Gruyter Mouton: 303–337. doi:10.1515/multi-2020-0119. hdl:10576/25979. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d Shockley, Mark Daniel (1 December 2020). The vowels of Urban Qatari Arabic (thesis). University of North Dakota. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ "Qatari Arabic". Arabic Perfect. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ The Report: Qatar 2015. Oxford Business Group. 2015. p. 12. ISBN 9781910068274.

- ^ Qotbah, Mohammed Abdullah (1990). Needs analysis and the design of courses in English for academic purposes : a study of the use of English language at the University of Qatar (PDF). etheses.dur.ac.uk (Thesis). Durham theses, Durham University. p. 8. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ "AJC Stunned by Qatar's Admission to Francophonie Organization". Global Jewish Advocacy. 14 October 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ^ The Report: Qatar 2015. Oxford Business Group. 2015. p. 15. ISBN 9781910068274.

Further reading

edit- Ferdinand, Klaus (1993). Ida Nicolaisen (ed.). Bedouins of Qatar. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 9780500015735. OCLC 990430539.