Russia–European Union relations are the international relations between the European Union (EU) and Russia.[1] Russia borders five EU member states: Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland; the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad is surrounded by EU members. Until the radical breakdown of relations following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the EU was Russia's largest trading partner and Russia had a significant role in the European energy sector. Due to the invasion, relations became very tense after the European Union imposed sanctions against Russia. Russia placed all member states of the European Union on a list of "unfriendly countries", along with NATO members (except Turkey), Switzerland, Ukraine, and several Asia-Pacific countries.[2]

| |

European Union |

Russia |

|---|---|

The bilateral relations of individual EU member states and Russia vary, though a 1990s common foreign policy outline towards Russia was the first such EU foreign policy agreed. Furthermore, four 'EU–Russia Common Spaces' were agreed as a framework for establishing better relations. In 2015, a European Parliament resolution stated that Russia was no longer a strategic partner with the EU[3] following the annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas.[4]

Relations between Russia and the EU became increasingly strained since the annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas, and the EU imposed several sanctions against the Russian Federation. The ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine launched in 2022 has caused already tense EU–Russian diplomatic relations to break down: the EU sent military aid to Ukraine, Russian assets in the EU were frozen and direct flights from the EU to Russia were suspended. On 23 November 2022, the European Parliament passed a motion declaring Russia a state sponsor of terrorism.[5]

Background

editThis background is a snapshot of the way things were before the complete breakdown of bilateral relations in the wake of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. The deterioration of relations is exemplified below in the Sanctions over Ukraine section.

Trade

editThe EU is Russia's largest trading partner, accounting for 52.3% of all foreign Russian trade in 2008 and 75% of foreign direct investment (FDI) stocks in Russia also come from the EU. The EU exported €105 billion of goods to Russia in 2008 and Russia exported €173.2 billion to the EU. 68.2% of Russian exports to the EU are accounted for by energy and fuel supplies. For details on other trade, see the table below:[6]

| Direction of trade | Goods | Services | FDI | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU to Russia | €105 billion | €18 billion | €17 billion | €140 billion |

| Russia to EU | €173.2 billion | €11.5 billion | €1 billion | €185.7 billion |

Russia and the EU are both members of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). The EU and Russia are currently implementing the common spaces (see below) and negotiation to replace the current Partnership and Cooperation Agreement to strengthen bilateral trade.[6]

Energy

editRussia has a significant role in the European energy sector. In 2007, the EU imported from Russia 185 million tonnes of crude oil, which accounted for 32.6% of total oil imports, and 100.7 million tonnes of oil equivalent of natural gas, which accounted for 38.7% of total gas imports.[7] A number of disputes in which Russia was using pipeline shutdowns in what was described in 2006 as "tool for intimidation and blackmail"[8] caused some in the EU by 2015 to notice that to source its energy from Russia was a problem, especially in the wake of the 2014 annexation of Crimea.[9]

During an anti-trust investigation initiated in 2011 against Gazprom a number of internal company documents were seized that documented a number of "abusive practices" in an attempt to "segment the internal [EU] market along national borders" and impose "unfair pricing".[10]

In August 2021 Russia has unexpectedly reduced volumes of gas sent to the EU, causing sudden gas price increases on the European market "to support its case in starting flows via Nord Stream 2".[11] The next month, it announced that "rapid" start up of the newly completed Nord Stream 2 pipeline that has been for long contested by various EU countries would resolve the problems.[11]

As of 2024, the number of Rosatom VVER nuclear power plants was 20. Two are located in Bulgaria, six in the Czech Republic, two in Finland, four in Hungary, and six in Slovakia.[12] Worries over sanctions caused them as a group to double their imports of Russian nuclear fuel for 2023.[13] Meanwhile a Polish industry forum published a piece entitled: "Anatomy of Dependence: How to Eliminate Rosatom from Europe" and noticed that "Any increase in the price of uranium sourced by EU countries would have a negligible impact on the cost of electricity generation. It is estimated that a 50% increase in the price of uranium translates into about a 5% increase in the price of electricity."[12] Overall, the fuel price paid to Russia by the EU inflated year-over-year by 34% and stood at an average of just under €1.2 million per ton in 2023.[13]

| Country | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|

| Czech Republic | 90 | 199 |

| Slovakia | 80 | 229 |

| Hungary | 104 | 103 |

| Finland | 37 | 20 |

Kaliningrad

editThe Russian exclave of Kaliningrad Oblast has, since 2004, been surrounded on land by EU members. As a result, the oblast has been isolated from the rest of the federation due to stricter border controls that had to be brought in when Poland and Lithuania joined the EU and further tightened before they joined the Schengen Area. The new difficulties for Russians in Kaliningrad to reach the rest of Russia is a small source of tension.

In July 2011, the European Commission put forward proposals to classify the whole of Kaliningrad as a border area. This would allow Poland and Lithuania to issue special permits for Kaliningrad residents to pass through those two countries without requiring a Schengen visa.[14] Between 2012 and 2016, visa-free travels were allowed between Kaliningrad region and northern Poland.[15]

After the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the EU banned Russian flights from EU airspace, leaving Kaliningrad inaccessible by direct flights to Russia.[16][17] The invasion and the 2021–2022 Belarus–European Union border crisis also led to delays of border crossing and trucking, damaging the import-dependent Kaliningrad economy.[18] Since the invasion the Russian military presence in Kaliningrad has escalated, with Russia threatening to station nuclear weapons in the oblast in response to Sweden and Finland's membership bids to NATO.[19]

Russian minorities in the EU

editThe OSCE mission monitoring the 2006 parliamentary elections in Latvia mentioned that

Approximately 400,000 people in Latvia, some 18 per cent of the total population, had not obtained Latvian or any other citizenship and therefore still had the status of "non-citizens." In the vast majority of cases, those were persons who migrated to Latvia from within the former Soviet Union, and their descendants. Non-citizens do not have the right to vote in any Latvian elections, although they can join political parties. To obtain citizenship, these persons must go through a naturalization process, which over 50,000 persons have done since the 2002 Saeima election. The OSCE claimed that the fact that a significant percentage of the adult population did not hold voting rights represented a continuing democratic deficit.[20]

As reported by the European Commissioner for Human Rights 2007 report on Latvia, in 2006 there were 411,054 non-citizens, 66.5% of them belonging to Russian minority.[21]

In 2017, there were 900,000 ethnic Russians in the Baltic States,[22][23][24] having declined from 1.7 million in 1989, the year of the last census during the Soviet era.[citation needed]

Beginning in 2019, instruction in Russian language would be gradually discontinued in private colleges and universities in Latvia, as well as general instruction in Latvian public high schools,[25] except for subjects related to culture and history of the Russian minority, such as Russian language and literature classes.[26]

Russian and EU public opinion

editA February 2014 poll conducted by the Levada Center, Russia's largest independent polling organization, found that nearly 80% of Russian respondents had a "good" impression of the EU. This changed dramatically in 2014 with the Ukrainian crisis resulting in 70% taking a hostile view of the EU compared to 20% viewing it positively.[27]

A Levada poll released in August 2018 found that 68% of Russian respondents believe that Russia needs to dramatically improve relations with Western countries. 42% of Russians polled said they had a positive view of the EU, up from 28% in May 2018.[28]

A Levada poll released in February 2020 found that 80% of Russian respondents believe that Russia and the West should become friends and partners. 49% of Russians polled said they had a positive view of the EU.[29] However, with the exception of Bulgaria, Slovakia and Greece, the share of residents in the rest of the EU countries polled by Pew Research Center with positive views of Russia is considerably below 50%.[30]

Framework initiatives

editSeveral framework initiatives were attempted between Russia and the EU since the end of the Cold War until the complete breakdown of bilateral relations in the wake of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, after which the EU applied sanctions against Russia.

Partnership and Cooperation Agreement

editThe legal basis for the relations between the EU and Russia is the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA). Signed in June 1994 and in force since December 1997, the PCA was supposed to be valid for 10 years. Thus, since 2007 it is annually automatically renewed, until replaced by a new agreement.[31] The PCA provides a political, economic and cultural framework for relations between Russia and the EU. It is primarily concerned with promoting trade, investment and harmonious economic relations. However, it also mentions the parties' shared "[r]espect for democratic principles and human rights as defined in particular in the Helsinki Final Act and the Charter of Paris for a new Europe" and a commitment to international peace and security.[32][33]

The Four Common Spaces

editRussia has chosen not to participate in the EU's European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), as it aspires to be an "equal partner" of the EU (as opposed to the "junior partnership" that Russia sees in the ENP)[citation needed]. Consequently, Russia and the EU agreed in 2005 to create four Common Spaces for cooperation in different spheres.[34] In practice there are no substantial differences (besides naming) between the sum of these agreements and the ENP Action Plans (adopted jointly by the EU and its ENP partner states). In both cases the final agreement is based on provisions from the EU acquis communautaire and is jointly discussed and adopted. For this reason, the Common Spaces receive funding from the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI), which also funds the ENP.

At the St Petersburg Summit in May 2003, the EU and Russia agreed to reinforce their co-operation by creating, in the long term, four common spaces in the framework of the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement of 1997: a common economic space; a common space of freedom, security and justice; a space of co-operation in the field of external security; and a space of research, education, and cultural exchange.

The Moscow Summit in May 2005 adopted a single package of roadmaps for the creation of the four Common Spaces. These expand on the ongoing cooperation as described above, set out further specific objectives, and determine the actions necessary to make the common spaces a reality. They thereby determine the agenda for co-operation between the EU and Russia for the medium-term.

The London Summit in October 2005 focused on the practical implementation of the Road Maps for the four Common Spaces.

Common Economic Space

editThe objective of the common economic space is to create an open and integrated market between the EU and Russia. This space is intended to remove barriers to trade and investment and promote reforms and competitiveness, based on the principles of non-discrimination, transparency, and good governance.

Among the wide range of actions foreseen, a number of new dialogues are to be launched. Cooperation will be stepped up on regulatory policy, investment issues, competition, financial services, telecommunications, transport, energy, space activities and space launching, etc. Environment issues including nuclear safety and the implementation of the Kyoto Protocol also figure prominently.

Common Space of Freedom, Security and Justice

editWork on this space took a large step forward with the conclusion of negotiations on the visa facilitation and the readmission agreements. Both the EU and Russia were in the process of ratifying these agreements. The visa dialogue would continue with a view to examine the conditions for a mutual visa-free travel regime as a long-term perspective. In a 15 December 2011 statement given after an EU–Russia summit, the President of the European Commission confirmed the launch of the "Common Steps towards visa-free travel" with Russia.[35] Russia hoped to sign a deal on visa free travel as early as January 2014.[36]

Cooperation on combating terrorism and other forms of international illegal activities such as money laundering, the fight against drugs and trafficking in human beings would continue as well as on document security through the introduction of biometric features in a range of identity documents. The EU support to border management and reform of the Russian judiciary system were among the highlights of this space.

With a view to contributing to the concrete implementation of the road map, the Justice and Home Affairs PPC met on 13 October 2005 and agreed to organise clusters of conferences and seminars, bringing together experts and practitioners on counter-terrorism, cyber-crime, document security and judicial cooperation. There was also agreement about developing greater cooperation between the European Border Agency (FRONTEX) and the Federal Border Security Service of Russia.

Common Space on External Security

editThe road map underlines the shared responsibility of the parties for an international order based on effective multilateralism, their support for the central role of the UN, and for the effectiveness in particular of the OSCE and the Council of Europe. The parties will strengthen their cooperation on security and crisis management in order to address global and regional challenges and key threats, notably terrorism and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMD). They will give particular attention to securing stability in the regions adjacent to Russian and EU borders (the "frozen conflicts" in Transnistria, Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Nagorno-Karabakh).

EU activities in this area are done in the framework of its Common Foreign and Security Policy.

Common Space on Research, Education, Culture

editThis space built on the long-standing relations with Russia through its participation in EU Research and Development activities and the 6th Framework Programme in particular, and under the TEMPUS programme. It aimed at capitalising on the strength of the EU and Russian research communities and cultural and intellectual heritage by reinforcing links between research and innovation and closer cooperation on education such as through convergence of university curricula and qualifications. It also laid a basis for cooperation in the cultural field. A European Studies Institute co-financed by both sides was set up in Moscow for the start of the academic year 2006/7.

Russia and the EU worked together under Horizon 2020, which ran from 2014 to 2020.[37]

Partnership for Modernization

editOn 18 November 2009, at the Russia-EU summit in Stockholm, one of the main vectors of deepening of strategic relations the initiative "Partnership for Modernization" (PM) was put forward.[38] The goal of the partnership is to assist in the solution of problems of modernization of economy of Russia and the corresponding adaptation of the entire complex of Russia-EU relations based on the experience of the existing dialogue mechanisms "sectoral" interaction of Russia and the EU.

At the summit in Rostov-on-Don (June 2010), leaders of Russia and the EU signed the joint statement on the "Partnership for Modernization".[39][40] The document sets the priorities and the scope for intensification of cooperation in the interests of modernization between Russia and the EU.

In accordance with the joint statement of the priority area of the "Partnership for Modernization" should include the following areas: expanding opportunities for investment in key sectors driving growth and innovation; enhancing and deepening bilateral trade and economic cooperation, and also creation of favorable conditions for small and medium-sized enterprises; promoting alignment of technical regulations and standards, as well as the high level of intellectual property protection; transportation; promote the development of sustainable low-carbon economy and energy efficiency, and support international negotiations on combating climate change; enhancing cooperation in innovation, research and development, and space; ensuring balanced development by taking measures in response to regional and social consequences of economic restructuring; ensuring the effective functioning of the judiciary and strengthening the fight against corruption; promote the development of relations between people and the strengthening of dialogue with civil society to promote the participation of people and business. This list of areas of cooperation is not exhaustive. As necessary can be added to other areas of cooperation. The EU and Russia will encourage implementation of specific projects within the framework of the partnership.

To coordinate this work, Russia and the EU defined the respective coordinators (Russian Deputy Minister A. A. Slepnev and EU Deputy General Director for external relations of the European Commission H. Mingarelli; since 2011, Director for Russia, European External Action Service Gunnar Wiegand).

According to the results of the analysis of existing formats of cooperation with European partners, it was determined that the PM should build on existing achievements within the formation of Four Common Spaces Russia-EU, but not replace, existing "road map" and not be the reason for the creation of new structural add-ons. The main mechanisms of the initiative of PM have been recognized sectoral dialogues Russia-EU.

The national coordinators in cooperation with co-chairs-Russia sectoral dialogues the EU has developed an implementation plan for PM, contains specific joint projects in the priority areas of cooperation.

On 11 May 2011, the Ministry of economic development of Russia held an enlarged meeting of representatives of the sectoral dialogues the EU-Russia involved in the implementation of the initiative "Partnership for modernization", chaired by the national focal points initiative.

During the meeting the parties discussed the progress of the project Work plan PM and has identified priorities for the second half of 2011, measures to support projects, including the attraction of resources of international financial institutions, as well as the participation of business in implementing the tasks of the PM.

In order to create financial mechanisms for cooperation in the framework of PM by Vnesheconombank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and Vnesheconombank and the European Investment Bank (EIB) has signed the relevant memoranda of understanding. The documents envisage the possibility of allocating the aggregate up to $2 billion to finance projects in the PfP, provided that they meet criteria of financial institutions and approval by the authorized management bodies of the parties.

As priority directions of financing selected areas such as energy efficiency, transport, innovation initiatives related to small and medium enterprises (including business incubators, technological parks, centers of business technology, infrastructure, financial services SMEs), as well as commercialization of innovations in several sectors, including the above, pharmaceuticals, and environmental protection.

On the sidelines of the Russia-EU summit in Nizhni Novgorod on 9–10 June 2011 signed joint report of the coordinators of the PM which summarizes the work accomplished and gives examples implemented to date, practical activities and projects within the work plan.

In the framework of the implementation of the PM work plan during the said summit was signed a provision on the establishment of a new Dialogue on trade and investment between the Ministry of economic development of the Russian Federation and the Directorate General for trade of the European Commission. Co-chair of the Dialogue on the Russian side is Deputy Minister of economic development of the Russian Federation A. A. Slepnev, the EU - Deputy Director General of the Directorate General for trade of the European Commission P. Balazs. The dialogue will cover trade and investment relations EU-Russia, including the obligations of the European Union and Russia in the WTO and current trade and economic agreements between the European Union and Russia.

Visa liberalization dialogue

editOn 4 May 2010, the EU and Russia raised the prospect of beginning negotiations on a visa-free regime between their territories.[41] However, it was announced by the Council of the EU that the EU is not completely ready to open up the borders due to high risk of increase in human trafficking and drug imports into Europe and because of the loose borders of Russia with Kazakhstan. They will instead work towards providing Russia with a "roadmap for visa-free travel." While this does not legally bind the EU to providing visa-free access to the Schengen area for Russian citizens at any specific date in the future, it does greatly improve the chances of a new regime being established and obliges the EU to actively consider the notion, should the terms of the roadmap be met. Russia on the other hand has agreed that should the roadmap be established, it will ease access for EU citizens for whom access is not visa-free at this point, largely as a result of Russian visa policy which states that "visa free travel must be reciprocal between states." Both the EU and Russia acknowledge, however, that there are many problems to be solved before visa-free travel is introduced.

The dialogue was temporarily frozen by the EU in March 2014 during the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation.[42] In 2015, Jean-Maurice Ripert, the French Ambassador to Russia, stated that France would be interested in abolishing short-term Schengen visas for Russians; in 2016, the Spanish Minister of Industry José Manuel Soria made a similar statement on behalf of Spain.[citation needed] In June 2016, EEAS released a Russian-language video describing the necessary conditions for the visa-free regime.[43] The same year, a number of EU officials, including the head of EEAS' Russia Division Fernando Andresen Guimarães, said that they would like to restart negotiations on visa abolishment;[44] the Czech President Milos Zeman also spoke out in favor of visa-free regime for Russians. On 24 May 2016, the German think tank DGAP released a report called "The Eastern Question: Recommendations for Western Policy", discussing the renewed Western strategy towards Russia in the wake of increased tensions between Putin's regime and EU. Their recommendations include visa liberalization for Russian citizens in order to "improve people-to-people contacts and to send a strong signal that there is no conflict with Russian society".[45] Likewise, the chairman of Munich Security Conference Wolfgang Ischinger suggested granting "visa-free entry to countries of the Schengen area for ordinary Russian citizens, who are not to blame for the Ukrainian crisis and have nothing to do with sanctions".[citation needed] On 29 August 2017, the German politician and member of Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe Marieluise Beck published a piece in Neue Zürcher Zeitung with a number of recommendations for EU on dealing with Russia and counteracting Kremlin propaganda; one of them is visa-free regime for Russians in order to incorporate Russians into Western values and promote democratic change in Russia.[46] In October 2018, the member of SPD and Bundestag deputy Dirk Wiese suggested granting visa-free EU entry to young Russians in order to facilitate student exchange programs.[47] In July 2019, the German politician and chairman of the Petersburg Dialogue Ronald Pofalla stated his support for visa-free regime for the young Russians, and said that he will be negotiating for it in the second half of 2019.[48] Later that month, the German Minister of Foreign Affairs Heiko Maas said that visa-free regime "is a matter we want to pursue further. We may not be able to decide it alone, but we intend to sit down with our Schengen partners to see what can be done".[49]

EU membership discussion

editAmong the most vocal supporters of Russian membership of the EU was former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi. In an article published to Italian media on 26 May 2002, he said that the next step in Russia's growing integration with the West should be EU membership.[50] On 17 November 2005, he commented in regards to the prospect of such a membership that he is "convinced that even if it is a dream ... it is not too distant a dream and I think it will happen one day."[51] Berlusconi has made similar comments on other occasions as well.[52] Later, in October 2008, he said: "I consider Russia to be a Western country and my plan is for the Russian Federation to be able to become a member of the European Union in the coming years" and stated that he had this vision for years.[53]

Russian permanent representative to the EU Vladimir Chizhov commented on this by saying that Russia has no plans of joining the EU.[54] Vladimir Putin has said that Russia joining the EU would not be in the interests of either Russia or the EU, although he advocated close integration in various dimensions including establishment of four common spaces between Russia and the EU, including united economic, educational and scientific spaces as it was declared in the agreement in 2003.[55][56]

Michael McFaul claimed in 2001 that Russia was "decades away" from qualifying for EU membership.[57] Former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder has said that though Russia must "find its place both in NATO, and, in the longer term, in the European Union, and if conditions are created for this to happen" that such a thing is not economically feasible in the near future.[58] Czech President Miloš Zeman stated that he "dreams" of Russia joining EU.[citation needed]

According to a number of surveys carried out by Deutsche Welle in 2012, from 36% to 54% of Russians supported Russia joining EU, and about 60% of them saw EU as an important partner for their country.[59][60][61][62] Young people in particular have a positive image of the European Union.[63]

Russian destabilization of EU states

editIn July 2009, central and eastern European leaders – including former presidents Václav Havel, Valdas Adamkus, Aleksander Kwaśniewski, Vaira Vīķe-Freiberga, Lech Wałęsa – signed an open letter stating:

"Our hopes that relations with Russia would improve and that Moscow would finally fully accept our complete sovereignty and independence after joining NATO and the EU have not been fulfilled. Instead, Russia is back as a revisionist power pursuing a 19th-century agenda with 21st-century tactics and methods. [...] It challenges our claims to our own historical experiences. It asserts a privileged position in determining our security choices. It uses overt and covert means of economic warfare, ranging from energy blockades and politically motivated investments to bribery and media manipulation in order to advance its interests and to challenge the transatlantic orientation of Central and Eastern Europe."[64]

— Valdas Adamkus, Martin Bútora, Emil Constantinescu, Pavol Demeš, Luboš Dobrovský, Mátyás Eörsi, István Gyarmati, Václav Havel, Rastislav Káčer, Sandra Kalniete, Karel Schwarzenberg, Michal Kováč, Ivan Krastev, Aleksander Kwaśniewski, Mart Laar, Kadri Liik, János Martonyi, Janusz Onyszkiewicz, Adam Daniel Rotfeld, Vaira Vīķe-Freiberga, Alexandr Vondra, Lech Wałęsa

Latvian journalist Olga Dragilyeva stated that "Russian-language media controlled by the Russian government and NGOs connected with Russia have been cultivating dissatisfaction among the Russian-speaking part of the population" in Latvia.[65] National security agencies in Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia have linked Moscow to local pro-Russian groups.[66] In June 2015, a Chatham House report stated that Russia used "a wide range of hostile measures against its neighbours", including energy cut-offs, trade embargoes, subversive use of Russian minorities, malicious cyber activity, and co-option of business and political elites.[67]

In 2015, UK media said that the Russian leadership under Putin saw the fracturing of the political unity within the EU and especially the political unity between the EU and the U.S. as among its main strategic goals,[68][69] one of the means in achieving this goal being rendering support to Europe's far-right and hard Eurosceptic political parties.[70][71] In October 2015, Putin said that Washington treated European countries "like vassals who are being punished, rather than allies."[citation needed]

On May 9, 2015, on the occasion of the attack by Albanian terrorists in the city of Kumanovo, the Putin-awarded and Russian intelligence agent,[72] as well as pro-Kremlin journalist Daria Aslamova published a commissioned article in the newspaper "Komsomolskaya Pravda", in which there was a map of "united Macedonia", including the "liberated" Pirin part of the region, which was declared "occupied" by Bulgaria. Bulgaria was accused of "supporting Albanian terrorists", regardless of the Bulgarian support it provided to the defense of Macedonia in 2001 and was declared "banished" from Orthodox civilization.[73] In the days, weeks and months after it was written, the article was shared on numerous Rashist and Putinist sites.

In November 2015, the president of Bulgaria, Rosen Plevneliev, said that Russia had launched a massive hybrid warfare campaign "aimed at destabilising the whole of Europe", giving repeated violations of Bulgarian airspace and cyber-attacks as examples.[74] In January 2016, senior UK government officials were reported to have registered their growing fears that "a new cold war" was now unfolding in Europe, with "Russian meddling" allegedly taking on a breadth, range and depth greater than previously thought: "It really is a new Cold War out there. Right across the EU we are seeing alarming evidence of Russian efforts to unpick the fabric of European unity on a whole range of vital strategic issues."[75] The situation prompted the US Congress to instruct James R. Clapper, the U.S. Director of National Intelligence, to conduct a major review of Russian clandestine funding of European parties over the previous decade.[75]

On numerous occasions Russia was also accused of actively supporting United Kingdom withdrawal from the European Union through channels such as Russia Today and the Russian Federation embassy in London.[76] An analysis of the Russian government's English-language news service, Sputnik, found "a systematic bias in favour of the "Out" campaign which was too consistent to be the result of accident or error."[77]

In February 2016, a film circulating in Hungary, in which recruited students expressed anger at the policy of the US, was identified as a version of a Russian movie with the same script funded by a pro-Putin organisation, Officers' Daughters.[78] Published in March 2016, Swedish security service Säpo's annual report stated that Russia was engaged in "psychological warfare" using "extreme movements, information operations and misinformation campaigns" aimed at policy makers and the general public.[79]

In June 2016, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov stated that Russia will never attack any NATO country, saying: "I am convinced that all serious and honest politicians know perfectly well than Russia will never attack a member state of NATO. We have no such plans."[80] He also said: "In our security doctrine it is clearly stated that one of the main threats to our safety is the further expansion of NATO to the east."[80]

In late 2016, media in a number of states accused Russia of preparing grounds for a possible armed take-over at their territories in future, including Finland,[81] Estonia[82] and Montenegro. In the latter an armed coup was actually in progress but prevented by security services on the day of election on 16 October, with over 20 people arrested.[83] A group of 20 citizens of Serbia and Montenegro "planned to break into the Montenegro Parliament on election day, kill Prime Minister Milo Djukanovic and bring a pro-Russian coalition to power" according to Montenegro chief prosecutor Milivoje Katnić, adding that the group was led by two Russian citizens who fled the country before the arrest and "unspecified number of Russian operatives" in Serbia who were deported shortly after.[84][85] A few days after the failed coup Leonid Reshetnikov was dismissed by Putin from his duties as head of Russian Institute for Strategic Studies, which also had its branch in Belgrade where it supported anti-NATO and pro-Russian parties.[86] In 2019, a number of Montenegrin politicians and pro-Russian activists were convicted for the attempted coup as well as two Russian GRU officers Eduard Shishmakov and Vladimir Popov (convicted in absentia).[87]

In 2017, a cache of email was leaked demonstrating funding of far-right and far-left movements in Europe through a Belarusian citizen Alyaksandr Usovsky who funnelled hundreds of thousands of euros from Russian nationalist and oligarch Konstantin Malofeyev and reporting to Russian State Duma Deputy Konstantin Zatulin. Usovsky confirmed the authenticity of the emails.[88]

In 2017, three Alternative for Germany Bundestag deputies confirmed that they together received $29,000 in sponsored private jet visit to Moscow, which caused significant controversy in Germany.[89]

In 2019, a transcript was published from a meeting in Moscow where representatives of Italian nationalist Lega party were offered "tens of millions of dollars" of funding. The delegation to Moscow included Italy's deputy prime minister Matteo Salvini.[90] In 2020 chat transcripts were published by Dutch media of far-right politician Thierry Baudet indicating inspiration on his anti-Ukraine actions and possible financial support from Vladimir Kornilov, a Russian described by Baudet as someone "who works for president Putin".[91]

In 2020, a Spanish court looked at transcripts of calls between a Catalan independence activist Victor Terradellas and a group of Russians who came forward with an offer of up to 10,000 military personnel, pay out of Catalan debt and recognition of Catalan independence by the Russian Federation in exchange for Catalan recognition of Crimea. Frequent arrivals of known GRU operative Denis Sergeev into Spain, coinciding with major Catalan independence events, raised a questions about involvement of GRU Unit 29155 in escalation of the protests.[92]

On 28 April 2021, the European Parliament passed a resolution that condemned Russia's "hostile behaviour towards and outright attacks on EU Member States" explicitly mentioning suspected GRU operation in the Czech Republic in 2014, the poisoning and imprisonment of Alexei Navalny and escalation of the war in Donbass. The resolution called, among other things, for discontinuation of the Nord Stream 2 project.[93]

According to a 2022 report, Russia has spent over $300 million since 2014 on covert subsidies to various political parties and movements globally, including European Union, in exchange of pushing for policies favorable for Russian political goals.[94]

In 2023, an international group of journalists published an analysis of documents prepared in 2021 by Russian Directorate for Cross-Border Cooperation, part of Presidential Administration, detailing plans for interventions securing "strategic interests of the Russian Federation" in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Russia planned to grow pro-Russian sentiment in these countries, build fear of "NATO militarization", create a large number of pro-Russian NGOs and increase share of pro-Russian politicians in elections. Similar documents published earlier detailed Russia's plans to include Belarus into Russian Federation and return Moldova on pro-Russian path.[95]

Russian political influence and financial links

editMoscow increased its efforts to expand its political influence using a wide range of methods,[97] including funding of political movements in Europe, increased spending on propaganda in European languages,[98] operating a range of media broadcasting in EU languages[99][100] and web brigades, with some observers suspecting the Kremlin of trying to weaken the EU and its response to the Ukrainian crisis.[101][102][103]

Russia has formed close ties with Eurosceptic and populist parties belonging to both ends of the political spectrum.[104] By the end of 2014, a number of European far-right and far-left[105] parties were receiving different forms of financial or organisational support from Russia in an attempt to build a common anti-European and pro-Russian front in the European Union.

Unlike in the Cold War, when Soviets largely supported leftist groups, a fluid approach to ideology now allows the Kremlin to simultaneously back far-left and far-right movements, greens, anti-globalists and financial elites. The aim is to exacerbate divides and create an echo chamber of Kremlin support.

— Peter Pomerantsev, Michael Weiss, "The Menace of Unreality: How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture and Money", The Interpreter Magazine, 2014

Among the far-right parties involved were the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ),[106] Alternative for Germany (AfD), National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD), France's National Front, Italy's Lega Nord,[107] Hungary's Jobbik, Bulgaria's Attack (Ataka), and Latvian Russian Union.[108][109][110] Among far-left parties, representatives of Die Linke, Communist Party of Greece, Syriza and others attended numerous events organized by Russia such as "conservative conferences" and the Crimean referendum. In the Europarliament, the European United Left–Nordic Green Left are described as "reliable partner" of Russian politics, voting against resolutions condemning events such as Russia's military intervention in Ukraine, and supporting Russian policies e.g. in Syria.[105]

Konstantin Rykov and Timur Prokopenko, both closely tied to United Russia and the Russian Federation's Presidential Administration, were the key figures in funneling money to these parties.[112] Agence France-Presse stated that "From the far right to the radical left, populist parties across Europe are being courted by Russia's Vladimir Putin who aims to turn them into allies in his anti-EU campaign" and that "A majority of European populist parties have sided with Russia over Ukraine."[102] During the Russian military intervention in Ukraine, British politicians Nigel Farage of the far-right and Jeremy Corbyn of the far-left both defended Russia, saying the West had "provoked" it.[113][114]

Luke Harding wrote in The Guardian that the Front National's MEPs were a "pro-Russian bloc."[115] In 2014, the Nouvel Observateur said that the Russian government considered the Front National "capable of seizing power in France and changing the course of European history in Moscow's favour."[116] According to the French media, party leaders had frequent contact with Russian ambassador Alexander Orlov and Marine Le Pen made multiple trips to Moscow.[117][118] In November 2014, Marine Le Pen confirmed a €9 million loan from a Russian bank to the Front National.[119] The Independent said the loans "take Moscow's attempt to influence the internal politics of the EU to a new level."[120] Reinhard Bütikofer stated, "It's remarkable that a political party from the motherland of freedom can be funded by Putin's sphere – the largest European enemy of freedom."[121] Boris Kagarlitsky said, "If any foreign bank gave loans to a Russian political party, it would have been illegal, or at least it would have been an issue which could lead to a lot of scandal" and the party would be required to register as a "foreign agent."[122] Le Pen denied a Mediapart report that a senior Front National member said it was the first installment of a €40 million loan.[119][120][123] In April 2015, a Russian hacker group published texts and emails between Timur Prokopenko, a member of Putin's administration, and Konstantin Rykov, a former State Duma deputy with ties to France, discussing Russian financial support to the Front National in exchange for its support of Russia's annexation of Crimea.[124]

In June 2015, Marine Le Pen launched a new political group within the European Parliament, Europe of Nations and Freedom (ENF), composed of members of the Front National, Party for Freedom, Lega Nord, the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ), Flemish Interest (VB) and the Congress of the New Right (KNP). Reviewing votes in the EU Parliament on resolutions critical of Russia or measures not in the Kremlin's interests (e.g., the European Union–Ukraine Association Agreement), Hungary's Political Capital Institute found that the future ENF members voted "no" in 93% of cases, European United Left–Nordic Green Left in 78% of cases, and Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy in 67% of cases.[125] The writers stated that "It would therefore be logical to conclude, as others have done before, that there is a pro-Putin coalition in the European Parliament consisting of anti-EU and radical parties."[125]

The Financial Times and Radio Free Europe reported on Syriza's ties with Russia and extensive correspondence with Aleksandr Dugin, who called for a "genocide" of Ukrainians.[126][127] The EUobserver reported that Tsipras had a "pro-Russia track record" and that Syriza's MEPs had voted against the Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement, criticism of the Russian annexation of Crimea, and criticism of the pressure on civil rights group Memorial.[128] The Moscow Times stated that "The terms used in Russia's anti-Europe rhetoric also seem to have infiltrated Tsipras' vocabulary."[129] Russia also developed ties with Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán (Fidesz), who praised Vladimir Putin's "illiberal democracy" and was described by Germany's former foreign minister Joschka Fischer as a "Putinist".[130] Hungary allowed a Russian billionaire to renovate a memorial in Budapest, which some Hungarians called illegal, to Soviet soldiers who died fighting against the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, and Putin visited it in February 2015.[131] Orban's government dropped plans to put the expansion of the Paks Nuclear Power Plant out to tender and awarded the contract to Rosatom after Russia offered a generous loan.[132] Zoltán Illés said that Russia was "buying influence".[132]

Two new organisations – European Centre for Geopolitical Analysis and "Agency for Security and Cooperation in Europe" (ASCE) – recruiting mostly European far-right politicians, were also heavily involved in positive public relations during the 2014 Russian military intervention in Ukraine, observing Donbas general elections and presenting a pro-Russian point of view on various events there.[133][134] In 2014, a number of officials in Europe and NATO provided circumstantial evidence that protests against hydraulic fracturing may be sponsored by Gazprom. Russian officials have on numerous occasions warned Europe that fracking "poses a huge environmental problem" in spite of Gazprom itself being involved in shale gas surveys in Romania (and not facing any protests) and reacted aggressively to any criticism by environmental organisations.[135]

A significant part of the funding of anti-EU and extremist parties passes through St Basil the Great fund operated by Konstantin Malofeev.[136][137]

In February 2015, a group of Spanish nationals was arrested in Madrid for joining a Russian-backed armed group in the war in Donbas. Travelling through Moscow, they were met by a "government official" and sent to Donetsk, where they saw French and other foreign fighters, "half of them communists, half Nazis".[139]

In March 2015, the Russian nationalist party Rodina organized the International Russian Conservative Forum in Saint Petersburg, inviting a majority of its far-right and far-left (including openly neo-Nazi) supporters from abroad, many of whom had visited a similar event in Crimea in 2014: Udo Voigt, Jim Dowson, Nick Griffin, Jared Taylor, Roberto Fiore, Georgios Epitidios (Golden Dawn) and others.[140][141][142][143]

Since 2012, a fund created by the Foreign Affairs Ministry of Russia (Fund for the Legal Protection and Support of Russian Federation Compatriots Living Abroad) has transferred €224,000 to the "Latvian Human Rights Committee", which was founded by pro-Russian politician Tatjana Ždanoka. Latvijas Televīzija reported that only projects which supported Russia's foreign policy objectives were eligible for funding.[144]

In June 2015, the European Parliament stated that Russia was "supporting and financing radical and extremist parties in the EU" and called for monitoring of such activities.[4] France's National Front, the UK Independence Party, and Jobbik voted against the resolution.[145] These and other extreme right organisations are part of Russia-sponsored World National-Conservative Movement.[146] In July 2016, Estonian foreign affairs minister Marina Kaljurand said, "The parade that we have seen of former and current European leaders to Moscow calling for rapprochement — and tacitly agreeing to the dismantling of Europe — has been disheartening for those of us who understand that a unified Europe with a strong American partnership is the only reason we have a choice at all about where our futures should be."[147]

In June 2016, Czech foreign minister Lubomír Zaorálek stated that Russia was supporting right-wing populists to "divide and conquer" the EU.[148] In October 2016, the EU held talks on Russian funding of far-right and populist parties.[66]

In 2018, Czech counter-intelligence service BIS published a report documenting significant increase of activity of Russia and China-backed actors to influence regulators and political bodies.[149] In 2020 a detailed analysis of Russian intelligence actions and active measures between 2002–2011 to prevent ballistic missile defense component from being deployed, involving "manipulation of media events, outputs, and reports and abusing cultural and social events". This also included attempts to recruit the Russian-speaking population in the country, but the majority was not interested in supporting the policy of Vladimir Putin.[150]

There are also ongoing concerns related to allegations that European Parliament members were illegally or unethically influenced by Russia. Such concerns have been raised several tiimes in 2023 and 2024 and dubbed "Russiagate".[151][152][153]

Intelligence activities

editA Russian spy, Sergey Cherepanov, operated in Spain from the 1990s to June 2010 under a false identity, "Henry Frith".[154]

In a 2013 report, the Security Information Service noted the presence of an "extremely high" number of Russian intelligence officers in the Czech Republic.[103] The Swedish Security Service's 2014 annual report named Russia as the biggest intelligence threat, describing its espionage against Sweden as "extensive".[155]

According to a May 2016 report for the European Council on Foreign Relations, Russia was engaged in "massive and voracious intelligence-gathering campaigns, fueled by still-substantial budgets and a Kremlin culture that sees deceit and secret agendas even where none exist."[156]

One of the main figures perceived as European far-right and far-left contact in Russia is Sergey Naryshkin,[157] who in 2016 was appointed as the chief of Russia's Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR).[158]

In 2018, the head of British MI6, Alex Younger, warned that "perpetual confrontation" with the West is core feature of Russian foreign policy.[159]

Since 2009, in Estonia alone 20 people were tried and convicted as operatives or agents of Russian intelligence services, which is the largest number of all NATO countries. Out of these, 11 convicts worked for FSB, two for SVR, five for GRU, and one was not disclosed. Seven people were low-grade intelligence sources or couriers, primarily involved into contraband of various goods (e.g. cigarettes) from and to Russia and thus easily recruited. More importantly, five of the convicted were officials of Estonian law enforcement and army.[160]

In March 2021, Bulgarian security services arrested six people, including officials in defence ministry of Bulgaria suspected of collecting intelligence for Russia. One of the arrested who has a double Russian-Bulgarian nationality was operating as the contact person between the suspects and Russian embassy. Earlier in 2020, five Russian diplomats and a technical assistant have been expelled from Bulgaria as involved in illegal intelligence operations.[161]

Cyberattacks

editIn 2007, following the Estonian government's decision to remove a statue of a Soviet soldier, the Baltic country's major commercial banks, government agencies, media outlets, and ATMs were targeted by a coordinated cyber attack which was later traced to Russia.[162]

In April 2015, the French television channel TV5 Monde was targeted by a cyber attack which claimed to represent ISIL but French sources said their investigation was leading to Russia.[163] In May 2015, the Bundestag's computer system was shut down for days due to a cyberattack carried out by a hacker group that was likely "being steered by the Russian state", according to the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution in Germany.[164] The agency's head, Hans-Georg Maaßen, said that, in addition to spying, "lately Russian intelligence agencies have also shown a willingness to conduct sabotage."[164]

British Prime Minister Theresa May accused Russia of "threatening the international order", "seeking to weaponise information" and "deploying its state-run media organisations to plant fake stories".[165] She mentioned Russia's meddling in the German federal election in 2017,[165] after German government officials and security experts said there was no Russian interference.[166]

Concerns about foreign influence in the 2018 Swedish general election have been raised by the Swedish Security Service and others, leading to various countermeasures.[167] According to the Oxford Internet Institute, eight of the top 10 "junk news" sources during the election campaign were Swedish, and "Russian sources comprised less than 1% of the total number of URLs shared in the data sample."[168]

In 2020, German prosecutors issued an arrest warrant for Dmitry Badin, a GRU operative, for his involvement in 2015 hacking of Bundestag.[169]

Military doctrines

editIn 2009, Wprost reported that Russian military exercises had included a simulated nuclear attack on Poland.[170] In June 2012, Russian general Nikolay Makarov said that "cooperation between Finland and NATO threatens Russia's security. Finland should not desire NATO membership, rather it should preferably have closer military cooperation with Russia."[171] In response, Finnish Prime Minister Jyrki Katainen said that "Finland will make its own decisions and [do] what is best for Finland. Such decisions will not be left to Russian generals."[171] In April 2013, Svenska Dagbladet reported that Russia had simulated a bombing run in March on the Stockholm region and southern Sweden, using two Tu-22M3 Backfire heavy bombers and four Su-27 Flanker fighter jets.[172] A nuclear attack against Sweden was part of the training exercises.[173]

In May 2014, Russia's Deputy Prime Minister Dmitri Rogozin joked that he would return in a TU-160 after his plane was barred from Romania's airspace. Requesting an explanation, Romania's foreign ministry stated that "the threat of using a Russian strategic bomber plane by a Russian deputy prime minister is a very grave statement under the current regional context."[174] Rogozin has also stated that Russia's defence sector has "many other ways of travelling the world besides tourist visas" and "tanks don't need visas".[175]

In October 2014, Denmark's Defence Intelligence Service stated that in June of the same year Russian Air Force jets "equipped with live missiles" had simulated an attack on the island of Bornholm as 90,000 people visited for the annual Folkemødet meeting.[176]

In November 2014, the European Leadership Network reviewed 40 incidents involving Russia in a report titled Dangerous Brinkmanship, finding that they "add up to a highly disturbing picture of violations of national airspace, emergency scrambles, narrowly avoided midair collisions, close encounters at sea, simulated attack runs, and other dangerous actions happening on a regular basis over a very wide geographical area."[177][178] In March 2015, Russia's ambassador to Denmark, Mikhail Vanin, stated that Danish warship "will be targets for Russian missiles" if the country joined the NATO missile defense system.[179] Danish foreign minister Martin Lidegaard said the statements were "inacceptable" and "crossed the line".[180] A few days later, Russian Foreign Ministry spokesman Aleksandr Lukashevich said that Russia could "neutralize" a missile defense system in Denmark.[181] In April 2015, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, and Iceland decided to increase their military cooperation, telling Aftenposten: "The Russian military are acting in a challenging way along our borders, and there have been several infringes on the borders of the Baltic nations. Russia's propaganda and political manoeuvering are contributing to sowing discord between the nations, as well as inside organisations like NATO and the EU".[182][183] In June 2015, Russia's ambassador to Sweden, Viktor Tatarintsev, told Dagens Nyheter that if Sweden joins NATO "there will be counter measures. Putin pointed out that there will be consequences, that Russia will have to resort to a response of the military kind and re-orientate our troops and missiles."[184]

From April 2013 to November 2015, Russia held seven large-scale military exercises (65,000 to 160,000 personnel) whereas NATO exercises were generally much smaller in size, with the largest composed of 36,000 personnel.[185] Estonia criticised Russia's military exercises, saying that they "dwarfed" NATO's and were offensive rather than defensive, "simulating the invasion of its neighbors, the destruction and seizure of critical military and economic infrastructure, and targeted nuclear strikes on NATO allies and partners."[147]

In 2016, Sweden revised its military strategy doctrine. Parliamentary Defense Committee chairman Allan Widman stated, "The old military doctrine was shaped after the last Cold War when Sweden believed that Russia was on the road to becoming a real democracy that would no longer pose a threat to this country and its neighbors."[186] In April 2016, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov stated that Russia would "have to take the necessary military-technical action" if Sweden joined NATO; Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Löfven responded, "We demand respect [...] in the same way that we respect other countries' decisions about their security and defence policies."[187]

Russian military activities in Ukraine and Georgia caused particular alarm in countries which are geographically close to Russia and those which experienced decades of Soviet military occupation.[188][189] Poland's foreign minister Witold Waszczykowski stated, "We have to reject any type of wishful thinking with regard to pragmatic cooperation with Russia as long as it keeps on invading its neighbours."[190] Following the annexation of Crimea, Lithuania reinstated conscription, increased its defense spending, called on NATO to deploy more troops to the Baltics, and published three guides on surviving emergencies and war.[191] Lithuanian president Dalia Grybauskaitė stated, "I think that Russia is terrorising its neighbours and using terrorist methods".[192] Estonia increased training of Estonian Defence League members and encouraged more citizens to own guns. Brigadier General Meelis Kiili stated, "The best deterrent is not only armed soldiers, but armed citizens, too."[189] In March 2017, Sweden decided to reintroduce conscription due to Russia's military drills in the Baltics and aggression in Ukraine.[193]

In his speech at the RUSI Land Warfare Conference in June 2018, the Chief of the General Staff Mark Carleton-Smith said that British troops should be prepared to "fight and win" against the "imminent" threat of hostile Russia.[194][195] Carleton-Smith said: "The misplaced perception that there is no imminent or existential threat to the UK – and that even if there was it could only arise at long notice – is wrong, along with a flawed belief that conventional hardware and mass are irrelevant in countering Russian subversion...".[195][196] In a November 2018 interview with the Daily Telegraph, Carleton-Smith said that "Russia today indisputably represents a far greater threat to our national security than Islamic extremist threats such as al-Qaeda and ISIL. ... We cannot be complacent about the threat Russia poses or leave it uncontested."[197]

In 2020, German media reported that members of German far-right extremist National Democratic Party (NPD) and The Third Way party attended military training in the Russian Federation.[198]

On July 28, 2024, Russian President Vladimir Putin threatens to deploy long-range missiles that could hit all of Europe, after the United States announced its intention to deploy long-range missiles in Germany from 2026.[199]

Russia's assassinations and abductions

editAlexander Litvinenko, who had defected from the FSB and become a British citizen, died from radioactive polonium-210 poisoning carried out in England in November 2006. Relations between the U.K. and Russia cooled after a British murder investigation indicated that Russia's Federal Protective Service was behind his poisoning. Investigation into the poisoning revealed traces of radioactive polonium left by the assassins in multiple places as they travelled across Europe, including Hamburg in Germany.

In September 2014, the FSB crossed into Estonia and abducted Eston Kohver, an officer of the Estonian Internal Security Service. Brian Whitmore of Radio Free Europe stated that the case "illustrates the Kremlin's campaign to intimidate its neighbors, flout global rules and norms, and test NATO's defenses and responses."[201]

Between 2015 and 2017, officers Denis Sergeev, Alexey Kalinin and Mikhail Opryshko, all from GRU Unit 29155 were frequently traveling to Spain, allegedly in relation to the upcoming 2017 Catalan independence referendum. The same group was also linked to a failed assassination attempt of arms dealer Emian Gebrev in Bulgaria in 2015 and interference with Brexit referendum in 2016.[202]

On 4 March 2018, Sergei Skripal, a former Russian military intelligence officer who acted as a double agent for the UK's intelligence services in the 1990s and early 2000s, and his daughter Yulia were poisoned with a Novichok nerve agent in Salisbury, England. The UK Prime Minister Theresa May requested a Russian explanation by the end of 13 March 2018. She said that the UK Government would "consider in detail the response from the Russian State" and in the event that there was no credible response, the government would "conclude that this action amounts to an unlawful use of force by the Russian State against the United Kingdom" and measures would follow.

In 2019, a Russian operative was arrested in Germany after he assassinated a Chechen refugee, Zelimkhan Khangoshvili. In response Germany expelled two Russian diplomats.[203]

Migration-related interference

editIn January 2016, several Finnish authorities suspected that Russians were assisting asylum seekers to enter Finland, and Yle, the national public-broadcasting company, reported that a Russian border guard had admitted the Federal Security Service's involvement in organising the traffic flow, prioritising families with small children.[204] In March, NATO General Philip Breedlove stated, "Together, Russia and the Assad regime are deliberately weaponizing migration in an attempt to overwhelm European structures and break European resolve".[205] A Russian state-run channel broadcast a story, supported by Sergey Lavrov on a news conference, that a 13-year-old German-Russian girl who had briefly disappeared had been raped by migrants in Berlin and that German officials were covering it up. The story contradicted investigation of the Berlin police, which found that the girl wasn't abducted or raped.[206] Germany's foreign minister suggested that Russia was using the case "for political propaganda, and to inflame and influence what is already a difficult debate about migration within Germany."[206]

In Bulgaria, a number of Russian citizens (most notably Igor Zorin and Yevgeniy Shchegolikhin) are involved in cooperation with far-right and anti-immigrant movements, for example organization of paramilitary trainings for "voluntary border patrols".[207]

Sabotage

editIn April 2015, the Russian Navy disrupted NordBalt cable-laying in Lithuania's exclusive economic zone.[208][209]

In April 2021, the Czech Republic expelled 18 Russian intelligence operatives working under diplomatic cover after police investigation linked two GRU officers (Alexander Mishkin and Anatoly Chepiga) to the 2014 Vrbětice ammunition warehouses explosions.[210] The same GRU group was later also linked to a series of ammunition depot explosions in Bulgaria, including 12 November 2011 near Lovnidol and 21 March 2015 in Iganovo.[211]

After the October 2022 German railway attack, the Green politician Anton Hofreiter told FUNKE media group that the sabotage reminded him of the disruption of the Nord Stream pipelines where the "trail leads to the Kremlin." "Maybe both were warning shots because we support Ukraine," Hofreiter added.[212] Meanwhile german police stated that there was no sign of any involvement by a foreign state.[213]

Propaganda

editRussian government funded media and political organisations have primarily targeted far-right circles in Europe, attempting to create an image of Russia as the last defender of traditional, conservative and Christian values:[214]

Putin, in his annual address at the end of 2013, when defending the discriminative "anti-gay propaganda law" from international criticism before the Sochi Olympic Games, practically put Russia in the role of the global "moral compass" of conservatism. Putin claimed that banning "propaganda of non-traditional relations" should not be regarded as discriminative, it is only about strengthening traditional family values, which is a guarantee of Russia's greatness. He also downplayed the Western approach of "so-called tolerance — genderless and infertile", and said that the "destruction of traditional values from the top" in the West is "inherently undemocratic because it is based on abstract ideas and runs counter to the will of the majority of people

— The Weaponization of Culture: Kremlin's Traditional Agenda and the Export of Values to Central Europe

Russian and pro-Russian media and organisations have produced fake stories and distorted real events. One of the most widely distributed fake stories was that of 13-year old Lisa F. In March 2017 a Russian TV team reportedly paid Swedish teenagers to stage a scene of anti-government protests in Rinkeby.[215] The scale of this campaign resulted in a number of EU countries taking individual actions. The Czech Republic noted that Russia had set up about 40 Czech-language websites publishing conspiracy theories and false reports.[216] According to the state secretary for European affairs, "The key goal of Russian propaganda in the Czech Republic is to sow doubts into the minds of the people that democracy is the best system to organise a country, to build negative images of the European Union and Nato, and [to] discourage people from participation in the democratic processes."[216] An analyst for the Lithuanian Armed Forces stated, "We have a pretty huge and long lasting disinformation campaign against our society".[217] Lithuania has given three-month bans to Russian channels; Foreign Minister Linas Linkevičius stated, "A lie is not an alternative point of view".[217] The head of Finland's governmental communication department, Markku Mantila, said that Russian propaganda sought to create suspicions against Finland's leaders, the European Union, and NATO. He stated, "There is a systematic lying campaign going on... It is not a question of bad journalism, I believe it is controlled from the center."[218]

European Union has taken a number of steps at various levels to counter hostile propaganda and disinformation. EU Action Plan Against Disinformation of 2018 explicitly mentions Russia as the main threat source and East StratCom Task Force is an EU body working since 2015 on recording, fact-checking and debunking hostile disinformation. Council of the EU also runs a Council disinformation working group (ERCHT) dedicated to analysis and planning on response to disinformation. A number of Eastern and Central Europe countries run their own open-source intelligence institutions whose objective is to analyze events and influence from Russia. Among these are Centre for Polish-Russian Dialogue and Understanding (CPRDIP), the Estonian Center of Eastern Partnership, or the Polish Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW).[219]

In November 2016, the EU Parliament passed an anti-propaganda resolution.[220] EU Disinformation Review is a news feed analysing and debunking most notable fake stories distributed in Russian media.[221] In 2018 the European Commission initiated a new Action Plan to counter "disinformation that fuels hatred, division, and mistrust in democracy" as well as interference with elections, "with evidence pointing to Russia as a primary source of these campaigns".[222]

In June 2021, a Russian advertising firm Fazze attempted to recruit numerous YouTube and Instagram influencers for paid posts spreading false claims about several COVID-19 vaccines manufactured by European companies.[223]

In 2022, European Parliament Special Committee on Foreign Interference in all Democratic Processes in the European Union, including Disinformation (INGE) draft "Report on foreign interference in all democratic processes in the European Union, including disinformation" condemned activities of RT (Russia Today), Sputnik and numerous other Russia agencies:[224]

The Kremlin's efforts to instrumentalise minorities in EU Member States by implementing so-called compatriot policies, particularly in the Baltic states and the Eastern Neighbourhood countries, as part of the geopolitical strategy of Putin's regime, whose aim is to divide societies in the EU, alongside the implementation of the concept of the 'Russian world', aimed at justifying expansionist actions by the regime; notes that many Russian 'private foundations', 'private enterprises', 'media organisations' and 'NGOs' are either state-owned or have hidden ties with the Russian state; stresses that it is of the utmost importance when engaging in dialogue with Russian civil society to differentiate between those organisations which stay clear of Russian governmental influence and those that have links to the Kremlin; recalls that there is also evidence of Russian interference and manipulation in many other Western liberal democracies, as well as active support for extremist forces and radical-minded entities in order to promote the destabilisation of the Union; notes that the Kremlin makes broad use of culture, including popular music, audiovisual content and literature, as part of its disinformation ecosystem; deplores Russia's attempts not to fully recognise the history of Soviet crimes and instead to introduce a new Russian narrative;

— European Parliament INGE draft report

Disputes and notable events

editRussian opposition to the invasion of Iraq

editRussia strongly opposed the U.S.-led 2003 invasion of Iraq. Some EU member states, including Poland and the United Kingdom, agreed to join the United States in the "coalition of the willing".[225] The foreign ministers of Russia, France and Germany made a joint declaration that they will "not allow" passage of a UN Security Council resolution authorising war against Iraq.[226]

Meat from Poland

editIn 2007, Russia imposed a ban on Polish meat exports (allegedly due of low quality and unsafe meat exported from the country[227]), which caused Poland to veto proposed EU–Russia pacts concerning issues such as energy and migration; an oil blockade on Lithuania; and concerns by Latvia and Poland on the Nord Stream 1 pipeline.[228] Later, Polish meat was allowed to be exported to Russia.[citation needed]

Gas disputes

editThe Russia–Ukraine gas dispute of 2009 damaged Russia's reputation as a gas supplier.[229][230][231] Afterwards, a deal was struck between Ukraine and the EU on 23 March 2009 to upgrade Ukraine's gas pipelines.[232][233] According to Russian Energy Minister Sergei Shmatko the plan appeared to draw Ukraine legally closer to the European Union and might harm Moscow's interests.[233] The Russian Foreign Ministry called the deal "an unfriendly act" (on 26 March 2009).[234] Professor Irina Busygina of the Moscow State Institution for Foreign Relations has said that Russia has better relations with certain leaders of some EU countries than with the EU as a whole because the EU has no prospect of a common foreign policy.[235]

In September 2012, the European Commission (EC) opened an antitrust investigation relating to Gazprom's contracts in central and eastern Europe.[236] Russia responded by enacting, also in September 2012, legislation hindering foreign investigations.[237] In 2013, the poorest members of the EU usually paid the highest prices for gas from Gazprom.[238]

The commission's investigation was delayed due to Russia's military intervention in Ukraine.[239] In April 2015, the EC accused Gazprom of unfair pricing and restricting competition.[240] The European Commissioner for Competition, Margrethe Vestager, stated that "All companies that operate in the European market – no matter if they are European or not – have to play by our EU rules. I am concerned that Gazprom is breaking EU antitrust rules by abusing its dominant position on EU gas markets."[241] Gazprom said it was "outside of the jurisdiction of the EU" and described itself as "a company which in accordance with the Russian legislation performs functions of public interest and has a status of strategic state-controlled entity."[242] Lithuanian president Dalia Grybauskaitė said that the Kremlin was using Gazprom as "a tool of political and economic blackmail in Europe".[243]

In October 2016, general Leonid Ivashov explained in Russian Channel One that Russia's engagement in the Syrian Civil War was critical to prevent construction of hydrocarbon pipelines from the Middle East to Europe, which would be catastrophic for Gazprom and, in turn, for the budget of Russia.[244][245]

Tensions over association agreements

editThe run-up to the 2013 Vilnius Summit between the EU and its eastern neighbours saw what The Economist called a "raw geopolitical contest" not seen in Europe since the end of the Cold War, as Russia attempted to persuade countries in its "near abroad" to join its new Eurasian Economic Union rather than sign Association Agreements with the EU.[246] The Russian government under president Putin succeeded in convincing Armenia (in September) and Ukraine (in November) to halt talks with the EU and instead begin negotiations with Russia.[247][248] Nevertheless, the EU summit went ahead with Moldova and Georgia proceeding towards agreements with the EU despite Russia's opposition.[249] Widespread protests in Ukraine resulted in then-President Viktor Yanukovych leaving Ukraine for Russia in February 2014. Russia subsequently began a military intervention in Ukraine. The European Union condemned this action as an invasion and imposed visa bans and asset freezes against some Russian officials.[250] The Council of the European Union stated that "Russia's violation of international law and the destabilisation of Ukraine [...] challenge the European security order at its core."[251]

Russia views some of the countries that applied to join the EU or NATO after the fall of the Iron Curtain as part of its sphere of influence.[248] It has criticised their admission and frequently said that NATO is "moving its infrastructure closer to the Russian border". The expansion of NATO into the Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia as well as the proposed ascension of Georgia and Ukraine are among Russia's main claims to NATO's encroachment of its sphere of influence.[252][253] NATO Deputy Secretary General Alexander Vershbow responded that NATO's major military infrastructure in Eastern Europe is no closer to the Russian border than since the end of the Cold War, and that Russia itself maintains a large military presence in neighbouring countries.[254]

Sanctions over Ukraine

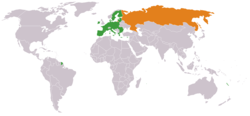

editCountries on Russia's "Unfriendly Countries List". Countries and territories on the list have imposed or joined sanctions against Russia.[255]

EU sanctions Russia over Ukraine

editThe 2014 annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation brought about on 17 March 2014 sanctions from the Council of the European Union upon the Russian Federation.[256] With the military intervention in Donbas, and the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine since 2022, they have been made more severe. The results have been the subject of much academic debate,[257][258][259][260][261] and many Parliamentary reports.[262][263][264]

Over the period when the Minsk Accords were in play, the EU sanctions also involved visa bans and freeze of assets of more than 150 individuals and more than 40 entities involved in these operations.[265][266][267] The EU sanctions have been continuously extended with increasing severity and are in force as of 2023.[268][269]

In May 2020, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and European Council President Charles Michel responded to calls from Russia for relaxation of the sanctions to facilitate the COVID-19 response explaining that the EU sanctions are "deliberately narrowly framed in order to limit the risks of unintended consequences or harm to the wider population" and none of them prevents "export of food or medicines, vaccines or medical equipment". As the original reasons for sanctioning were not removed by Russia, the sanctions were extended for another year.[270]

The "personalized sanctions" imposed on individuals such as Russian functionaries and oligarchs have broadened since their inception in 2014.[269] The following non-exhaustive list gives a flavour of the type and breadth of the sanctions as well as particular events in the relationship:

- 17.03.2014 Sanctions initiated[256]

- 22.07.2015 Council of the European Union takes action following the downing of flight MH17

- 02.03.2022 SWIFT code ban for seven Russian banks

- 02.03.2022 suspension of broadcasting of Russia Today and Sputnik

- 03.03.2022 Misappropriation of Ukrainian state funds: EU prolongs restrictive measures

- 09.03.2022 EU agrees new measures targeting Belarus and Russia

- 13.04.2022 EU introduces exceptions to restrictive measures to facilitate humanitarian activities

- 21.07.2022 "Maintenance and alignment" package of sanctions in response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine

- 20.10.2022 EU sanctions three individuals and one entity in relation to the use of Iranian drones in Russian aggression

- 23.11.2022 European Parliament declares Russia a state sponsor of terrorism[5]

- 28.11.2022 EU adds violation of sanctions to list of EU crimes

- 04.02.2023 EU agrees on level of price cap for Russian petroleum products

In March 2022, the EU initiated a "Freeze and Seize Task Force" under Commissioner for Justice Didier Reynders, to disburse to Ukraine funds which were left in the coffers of its banks by Russian oligarchs.[271][272] As well in March the Russian Elites, Proxies, and Oligarchs Task Force was set up between the EU, G7 countries and Australia.[271][273]

On 25 March 2022 the European Commission and the United States made a joint statement on European Energy Security, which committed the EU amongst other things "to terminate EU dependence on Russian fossil fuels by 2027."[274][275]

To take effect on 1 July 2024 were tariffs on cereals and oilseeds from Russia and Belarus. Trade ministers also asked the European Commission of Ursula von der Leyen to draw up a plan to place import duties on food, medicines and nuclear fuel from Russia. The EU has set the tariffs on Russian wheat at €95 per tonne.[276]

According to the European Council's timeline of EU restrictive measures against Russia over the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the EU has imposed 10 packages of sanctions in response since the eve of the invasion. The following "package of sanctions" timeline show that they have been continuously extended, increasing in severity and are in force as of 2023.[269]

- 23.02.2022 1st package of sanctions in response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine

- 25.02.2022 2nd package

- 02.03.2022 3rd package

- 15.03.2022 4th package

- 08.04.2022 5th package

- 03.06.2022 6th package

- 21.07.2022 7th package[277]

- 06.10.2022 8th package

- 16.12.2022 9th package

- 15.02.2023 10th package

- 23.06.2023 11th package[278]

- 20.06.2024 14th package, includes first liquid natural gas sanctions[279]

On 2 November 2024 Russia applied to the EU for a tariff exemption on 30,000 tonnes of butter.[280]