Fasilides (Ge'ez: ፋሲለደስ; Fāsīladas; 20 November 1603 – 18 October 1667), also known as Fasil,[2] Basilide,[3] or Basilides (as in the works of Edward Gibbon), was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1632 to his death on 18 October 1667, and a member of the Solomonic dynasty. His throne name was Alam Sagad (Ge'ez: ዓለም ሰገድ).

| Fasilides ዓፄ ፋሲለደስ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negusa Nagast | |||||||||

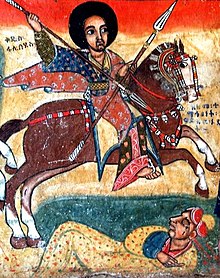

Mural depicting Emperor Fasilides at Ura Kidane Mehret Church, Ethiopia | |||||||||

| Emperor of Ethiopia | |||||||||

| Reign | 1632 – 18 October 1667 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Susenyos I | ||||||||

| Successor | Yohannes I | ||||||||

| Born | 20 November 1603 Bulga, Shewa, Ethiopian Empire | ||||||||

| Died | 18 October 1667 (aged 63) Azezo, Ethiopian Empire | ||||||||

| Issue | Four sons and one daughter, including Yohannes I and David[1] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynasty | House of Solomon | ||||||||

| Father | Susenyos I | ||||||||

| Mother | Sahle Work | ||||||||

| Religion | Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo | ||||||||

Renowned as the founder of Gondar, the capital of the Ethiopian Empire, Fasilides ushered in the Gondarine period. Notably, he confiscated and exiled the Jesuits, while also establishing security alliances with neighboring Islamic sultanates. Additionally, he played a crucial role in leading the campaign against the Agaw rebels. In 1666, following his son Dawit's rebellion, Fasilides had him imprisoned in Wehni. The emperor himself died a year later and was laid to rest in a monastery on Daga Island in Lake Tana.

History

editBeing of Amhara descent,[4] he was the son of Emperor Susenyos I and Empress Sahle Work (Ge'ez: ሣህለወርቅ) (throne name) ለ (name) of Wagda Katata and Merhabete. Emperor Fasilides was born at Magezez, Bulga in the Shewa region. His paternal grandfather's name was also Fasilides. He was builder of the Fasil palace.

Fasilides was proclaimed emperor in 1630 during a revolt led by Sarsa Krestos, but did not reach the throne until his father abdicated in 1632. Once he became emperor, Fasilides immediately restored the official status of the traditional Ethiopian Orthodox Church. He sent for a new abuna from the patriarch of Alexandria, restoring the ancient relationship that had been allowed to lapse. He confiscated the lands of the Jesuits at Dankaz and elsewhere in the empire and exiled them to Fremona. When he heard that the Portuguese bombarded Mombasa, Fasilides assumed that Afonso Mendes, the Roman Catholic prelate, was behind the act, and banished the remaining Jesuits from his lands. Mendes and most of his followers made their way back to Goa, being robbed or imprisoned several times on the way. In 1665, he ordered the "Books of the Franks"—the remaining religious writings of the Catholics—burnt.

Fasilides is commonly credited with founding the city of Gondar in 1636, establishing it as Ethiopia's capital.[5] Whether or not a community existed here before he made it his capital is unknown. Amongst the buildings he had constructed there are the beginnings of the complex later known as Fasil Ghebbi, as well as some of the earliest of Gondar's fabled 44 churches: Adababay Iyasus, Adababay Tekle Haymanot, Atatami Mikael, Gemjabet Mariyam, Fit Mikael, and Qeddus Abbo.[6] He is also credited with building seven stone bridges in Ethiopia, notably the Sebara Dildiy bridge (11°13′3.64″N 37°52′36.41″E / 11.2176778°N 37.8767806°E); as a result all old bridges in Ethiopia are often commonly believed to be his work.[7]

Emperor Fasilides also built the Cathedral Church of St Mary of Zion at Axum. Fasilides' church is known today as the "Old Cathedral" and stands next to a newer cathedral built by Emperor Haile Selassie.

The rebellion of the Agaw in Lasta, which had begun under his father, continued into his reign and for the rest of his reign he made regular punitive expeditions into Lasta. The first, in 1637, went badly, for at the Battle of Libo his men panicked before the Agaw assault and their leader, Melka Kristos, entered Fasilides' palace and took the throne for himself. Fasilides quickly recovered and sent for help to Qegnazmach Dimmo, governor of Semien, and his brother Gelawdewos, governor of Begemder. These marched on Melka Kristos, who was still at Libo, where he was killed and his men defeated. The next year Fasilides marched into Lasta; according to James Bruce, the Agaw retreated to their mountain strongholds, and "almost the whole army perished amidst the mountains; great part from famine, but a greater still from cold, a very remarkable circumstance in these latitudes."[8]

Foreign diplomacy

editSoon after he took the throne from his father, Fasilides ended all forms of contact between Ethiopia and Europe, expelling all European Jesuits and their missionaries while forming security pacts with the surrounding Islamic sultanates and initiating diplomatic relations with Islamic kingdoms such as the Safavids, Ottomans, Mughals and the Imams of Yemen. This isolation of the Ethiopian empire from Europe lasted more than two centuries.[9]

Fasilides tried in 1642–7 to establish diplomatic relations with Al-Mutawakkil Isma'il, the Zaydi Imam of Yemen. When Massawa was occupied by the Ottoman Empire, the Ethiopian Emperor Fasilides attempted to develop a new trade route via Beylul. His choice fell on Beylul, because this port was beyond the Ottoman sphere of control and directly opposite the harbor of Mocha in Yemen. In 1642 he sent a message to the Imam of Yemen al-Mu'ayyad Mohammed to gain his support for this project. Since al-Mu'ayyad Mohammed and his son al-Mutawakkil Isma'il assumed that Fasilides was interested in a conversion to Islam, a Yemeni embassy was sent to Gondar in 1646. However, when the Yemenis understood Fasilides' actual motives, their enthusiasm sank and the project was abandoned.[10]

He also dispatched an envoy to India in 1664–5, extending congratulations to Aurangzeb for his ascension to the Mughal Empire throne. The delegation reportedly presented several valuable offerings to the Mughal Emperor, such as slaves, ivory, horses, zebras, a set of intricately adorned silver pocket pistols, and various other exotic gifts.[11]

In 1666, after his son Dawit rebelled, Fasilides had him incarcerated at Wehni, reviving the ancient practice of confining troublesome members of the Imperial family to a mountaintop, as they had once been confined at Amba Geshen.

Death

editFasilides died at Azezo in 1667, 8 kilometres (5 miles) south of Gondar, and his body was interred at St. Stephen's, a monastery on Daga Island in Lake Tana. When Nathaniel T. Kenney was shown Fasilides' remains, he saw a smaller mummy also shared the coffin. A monk told Kenney that it was Fasilides' seven-year-old son Isur, who had been smothered in a crush of people, had come to pay homage to the new king.[12]

Descendants

editFasilides had three sons (of which two died before coming of age) and three daughters.[13]

- Yohannes I was the eldest son and successor.[13]

- His two other sons (Dawit and Isuor) died before Fasilides.[13][14]

- Theoclea was his eldest daughter, she married one of her father's retainer Laeka Krestos, a son of noblemen Malkae Krestos.[13]

- Kedeste Krestos was his second daughter, she married and had issue.[13]

- Sabla Wangel was his third daughter. It's through her line that Emperor Tewodros II claimed Solomonic descent from Fasiliades, almost two centuries later.[13]

References

edit- ^ Budge, E. A. Wallis (1928). A History of Ethiopia: Nubia and Abyssinia (Volume 2). London: Methuen & Co. p. 397.

- ^ Woredekal, Solomon (1985). "Restoration of historical monuments of Gondar". Annales d'Éthiopie. 13: 119. doi:10.3406/ethio.1985.926. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ Wion, Anaïs (2012). "Fasiladas". Dictionary of African Biography. Vol. 2. OUP. pp. 353–54. ISBN 9780195382075.

- ^ Danver, Steven L (2015). Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues. Routledge. p. 16. ISBN 9781317464006.

- ^ See the discussion in Solomon Getamun, History of the City of Gondar (Africa World Press, 2005), pp. 1-4

- ^ Getamun, City of Gondar, p. 5

- ^ There are many lists of these seven bridges; an example can be found in Richard Pankhurst, Economic History of Ethiopia (Addis Ababa: Haile Selassie University Press, 1968), pp. 297f

- ^ James Bruce, Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile (1805 edition), vol. 3, pp. 435-437

- ^ Feleke, Elehu, and Poluha, Eva. Thinking Outside the Box: Essays on the History and (Under)Development of Ethiopia. United Kingdom, Xlibris US, 2016.

- ^ Various, Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History, BRILL, 2016, p. 585,

- ^ Bernier, Travels in the Mogul Empire, A.D. 1656-1668, trans. Archibald Constable (Oxford: University Press, 1916), pp. 133-146

- ^ Nathaniel T. Kenney, "Ethiopian Adventure", National Geographic, 127 (1965), p.557.

- ^ a b c d e f Montgomery-Massingberd, Hugh (1980). "The Imperial House of Ethiopia". Burke's royal families of the world : 2. vol. London: Burke's Peerage. p. 46. ISBN 9780850110296. OCLC 1015115240.

- ^ Nathaniel T. Kenney, "Ethiopian Adventure", National Geographic, 127 (1965), p.557.

Further reading

edit- Emeri Johannes van Donzel, A Yemenite Embassy to Ethiopia 1647-1649 (Äthiopistische Forschungen Band 21) (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 1986)

External links

edit- Media related to Fasilides of Ethiopia at Wikimedia Commons