Hyaluronidase-1 is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the HYAL1 gene.[5][6][7]

Function

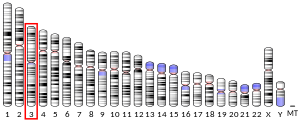

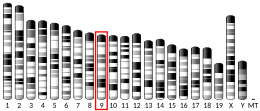

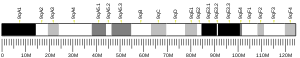

editThis gene encodes a lysosomal hyaluronidase. Hyaluronidases intracellularly degrade hyaluronan, one of the major glycosaminoglycans of the extracellular matrix. Hyaluronan is thought to be involved in cell proliferation, migration and differentiation. This enzyme is active at an acidic pH and is the major hyaluronidase in plasma. Mutations in this gene are associated with mucopolysaccharidosis type IX, or hyaluronidase deficiency. The gene is one of several related genes in a region of chromosome 3p21.3 associated with tumor suppression. Multiple transcript variants encoding different isoforms have been found for this gene.[7]

Structure

editHYAL1 was first purified from human plasma and urine.[5][6] The enzyme is 435 amino acids long with a molecular weight of 55-60 kDa.[6][8]

The crystal structure of HYAL1 was determined by Chao, Muthukumar, and Herzberg.[9] The enzyme is composed of two closely associated domains: a N-terminal catalytic domain (Phe22-Thr352) and a smaller C-terminal domain (Ser353-Trp435).[9] The catalytic domain adopts a distorted (β/α)8 barrel fold similar to that of bee venom hyaluronidase.[9] Within the catalytic domain, residues such as Tyr247, Asp129, Glu131, Asn350, and Tyr202 play important roles in the cleavage of the β1→4 linkage between N-acetylglucosamine and glucuronic acid units in hyaluronan.[10]

Mechanism

editHYAL1 is responsible for the hydrolysis of intracellular hyaluronan of all sizes into fragments as small as tetrasaccharides.[9]

In the optimal pH state of 4.0, Asp129 and Glu131 share a proton.[10] Intermolecular resonance in the amide bond in the N-acetylglucosamine unit of the bound hyaluronan polymer leads to a transition state with a positive charge on the nitrogen and an oxyanion nucleophile, which is stabilized by hydrogen bond interactions with Tyr247, that can perform an intramolecular attack on the electrophilic carbon.[10] This attack forms a 5-membered ring that is stabilized by the negative charge of Asp129 that forms as the leaving hydroxyl group of the glucuronic acid unit takes the proton from Glu131.[10] The now negatively charged Glu131 is primed to activate a water molecule for the hydrolysis of the intermolecular ring intermediate to restore N-acetylglucosamine.[10]

Tyr202 and Asn350, while not directly involved in the β1→4 linkage cleavage, were identified to be important to HYAL1 function.[10] HYAL1 uses Tyr202 as a substrate binding determinant and also requires proper glycosylation of Asn350 for full enzymatic function.[10]

The optimal pH range for HYAL1 function is 4.0 to 4.3, though HYAL1 is still 50-80% active at pH 4.5.[11][12]

Disease Relevance

editHYAL1 is implicated in several types of cancers, likely due to the angiogenic effects of HYAL1-cleaved hyaluronan fragments.[13][14] In bladder, prostate, and head and neck carcinomas, elevated hyaluronan and HYAL1 levels are found in tumor cells, tissues, and related body fluids (e.g. urine for bladder cancer and saliva for head and neck cancer).[15][16][17][18] Urinary hyaluronan and hyaluronidase levels, measured by the HA-HAase test, have ~88% accuracy in detecting bladder cancer, regardless of the tumor grade and stage.[19]

In breast cancer, HYAL1 is also overexpressed in cell lines MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 and invasive duct cancer tissues and metastatic lymph nodes.[20] Higher HYAL1 expression has also been detected in primary tumor tissue from patients with subsequent brain metastases versus those without.[21]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000114378 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000010051 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b Frost GI, Csóka AB, Wong T, Stern R, Csóka TB (July 1997). "Purification, cloning, and expression of human plasma hyaluronidase". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 236 (1): 10–5. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1997.6773. PMID 9223416.

- ^ a b c Csóka AB, Frost GI, Wong T, Stern R, Csóka TB (November 1997). "Purification and microsequencing of hyaluronidase isozymes from human urine". FEBS Letters. 417 (3): 307–10. Bibcode:1997FEBSL.417..307C. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(97)01309-4. PMID 9409739. S2CID 44929703.

- ^ a b "Entrez Gene: HYAL1 hyaluronoglucosaminidase 1".

- ^ Tan JX, Wang XY, Su XL, Li HY, Shi Y, Wang L, Ren GS (2011). "Upregulation of HYAL1 expression in breast cancer promoted tumor cell proliferation, migration, invasion and angiogenesis". PLOS ONE. 6 (7): e22836. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...622836T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022836. PMC 3145763. PMID 21829529. (Retracted, see doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0277500, PMID 36342948)

- ^ a b c d Chao KL, Muthukumar L, Herzberg O (June 2007). "Structure of human hyaluronidase-1, a hyaluronan hydrolyzing enzyme involved in tumor growth and angiogenesis". Biochemistry. 46 (23): 6911–20. doi:10.1021/bi700382g. PMID 17503783.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Zhang L, Bharadwaj AG, Casper A, Barkley J, Barycki JJ, Simpson MA (April 2009). "Hyaluronidase activity of human Hyal1 requires active site acidic and tyrosine residues". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (14): 9433–42. doi:10.1074/jbc.M900210200. PMC 2666596. PMID 19201751.

- ^ Lokeshwar VB, Rubinowicz D, Schroeder GL, Forgacs E, Minna JD, Block NL, Nadji M, Lokeshwar BL (April 2001). "Stromal and epithelial expression of tumor markers hyaluronic acid and HYAL1 hyaluronidase in prostate cancer". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (15): 11922–32. doi:10.1074/jbc.M008432200. PMID 11278412. S2CID 23511756.

- ^ Triggs-Raine B, Salo TJ, Zhang H, Wicklow BA, Natowicz MR (May 1999). "Mutations in HYAL1, a member of a tandemly distributed multigene family encoding disparate hyaluronidase activities, cause a newly described lysosomal disorder, mucopolysaccharidosis IX". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (11): 6296–300. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.6296T. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.11.6296. PMC 26875. PMID 10339581.

- ^ Slevin M, Krupinski J, Kumar S, Gaffney J (August 1998). "Angiogenic oligosaccharides of hyaluronan induce protein tyrosine kinase activity in endothelial cells and activate a cytoplasmic signal transduction pathway resulting in proliferation". Laboratory Investigation; A Journal of Technical Methods and Pathology. 78 (8): 987–1003. PMID 9714186.

- ^ Rooney P, Kumar S, Ponting J, Wang M (March 1995). "The role of hyaluronan in tumour neovascularization (review)". International Journal of Cancer. 60 (5): 632–6. doi:10.1002/ijc.2910600511. PMID 7532158. S2CID 19133429.

- ^ Eissa S, Kassim SK, Labib RA, El-Khouly IM, Ghaffer TM, Sadek M, Razek OA, El-Ahmady O (April 2005). "Detection of bladder carcinoma by combined testing of urine for hyaluronidase and cytokeratin 20 RNAs". Cancer. 103 (7): 1356–62. doi:10.1002/cncr.20902. PMID 15717321. S2CID 20271337.

- ^ Aboughalia AH (January 2006). "Elevation of hyaluronidase-1 and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 helps select bladder cancer patients at risk of invasion". Archives of Medical Research. 37 (1): 109–16. doi:10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.04.019. PMID 16314195.

- ^ Hautmann Stefan H.; Lokeshwar Vinata B.; Schroeder Grethchen L.; Civantos Francisco; Duncan Robert C.; Gnann Ralf; Friedrich Martin G.; Soloway Mark S. (2001-06-01). "ELEVATED TISSUE EXPRESSION OF HYALURONIC ACID AND HYALURONIDASE VALIDATES THE HA-HAase URINE TEST FOR BLADDER CANCER". Journal of Urology. 165 (6 Part 1): 2068–2074. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)66296-9. PMID 11371930.

- ^ Schroeder GL, Lorenzo-Gomez MF, Hautmann SH, Friedrich MG, Ekici S, Huland H, Lokeshwar V (September 2004). "A side by side comparison of cytology and biomarkers for bladder cancer detection". The Journal of Urology. 172 (3): 1123–6. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000134347.14643.ab. PMID 15311054.

- ^ Lokeshwar VB, Obek C, Pham HT, Wei D, Young MJ, Duncan RC, Soloway MS, Block NL (January 2000). "Urinary hyaluronic acid and hyaluronidase: markers for bladder cancer detection and evaluation of grade". The Journal of Urology. 163 (1): 348–56. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(05)68050-0. PMID 10604388.

- ^ Tan JX, Wang XY, Li HY, Su XL, Wang L, Ran L, Zheng K, Ren GS (March 2011). "HYAL1 overexpression is correlated with the malignant behavior of human breast cancer". International Journal of Cancer. 128 (6): 1303–15. doi:10.1002/ijc.25460. PMID 20473947. S2CID 205941298.

- ^ Witzel I, Marx AK, Müller V, Wikman H, Matschke J, Schumacher U, Stürken C, Prehm P, Laakmann E, Schmalfeldt B, Milde-Langosch K, Oliveira-Ferrer L (April 2017). "Role of HYAL1 expression in primary breast cancer in the formation of brain metastases". Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 162 (3): 427–438. doi:10.1007/s10549-017-4135-6. PMID 28168629. S2CID 20477034.

Further reading

edit- Wei MH, Latif F, Bader S, Kashuba V, Chen JY, Duh FM, Sekido Y, Lee CC, Geil L, Kuzmin I, Zabarovsky E, Klein G, Zbar B, Minna JD, Lerman MI (April 1996). "Construction of a 600-kilobase cosmid clone contig and generation of a transcriptional map surrounding the lung cancer tumor suppressor gene (TSG) locus on human chromosome 3p21.3: progress toward the isolation of a lung cancer TSG". Cancer Research. 56 (7): 1487–92. PMID 8603390.

- Natowicz MR, Short MP, Wang Y, Dickersin GR, Gebhardt MC, Rosenthal DI, Sims KB, Rosenberg AE (October 1996). "Clinical and biochemical manifestations of hyaluronidase deficiency". The New England Journal of Medicine. 335 (14): 1029–33. doi:10.1056/NEJM199610033351405. PMID 8793927.

- Csóka AB, Frost GI, Heng HH, Scherer SW, Mohapatra G, Stern R, Csóka TB (February 1998). "The hyaluronidase gene HYAL1 maps to chromosome 3p21.2-p21.3 in human and 9F1-F2 in mouse, a conserved candidate tumor suppressor locus". Genomics. 48 (1): 63–70. doi:10.1006/geno.1997.5158. PMID 9503017.

- Triggs-Raine B, Salo TJ, Zhang H, Wicklow BA, Natowicz MR (May 1999). "Mutations in HYAL1, a member of a tandemly distributed multigene family encoding disparate hyaluronidase activities, cause a newly described lysosomal disorder, mucopolysaccharidosis IX". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (11): 6296–300. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.6296T. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.11.6296. PMC 26875. PMID 10339581.

- Frost GI, Mohapatra G, Wong TM, Csóka AB, Gray JW, Stern R (February 2000). "HYAL1LUCA-1, a candidate tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 3p21.3, is inactivated in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas by aberrant splicing of pre-mRNA". Oncogene. 19 (7): 870–7. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1203317. PMID 10702795. S2CID 31039963.

- Shuttleworth TL, Wilson MD, Wicklow BA, Wilkins JA, Triggs-Raine BL (June 2002). "Characterization of the murine hyaluronidase gene region reveals complex organization and cotranscription of Hyal1 with downstream genes, Fus2 and Hyal3". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (25): 23008–18. doi:10.1074/jbc.M108991200. PMID 11929860. S2CID 24252110.

- Lokeshwar VB, Schroeder GL, Carey RI, Soloway MS, Iida N (September 2002). "Regulation of hyaluronidase activity by alternative mRNA splicing". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (37): 33654–63. doi:10.1074/jbc.M203821200. PMID 12084718. S2CID 8385249.

- Junker N, Latini S, Petersen LN, Kristjansen PE (2003). "Expression and regulation patterns of hyaluronidases in small cell lung cancer and glioma lines". Oncology Reports. 10 (3): 609–16. doi:10.3892/or.10.3.609 (inactive 1 November 2024). PMID 12684632.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Franzmann EJ, Schroeder GL, Goodwin WJ, Weed DT, Fisher P, Lokeshwar VB (September 2003). "Expression of tumor markers hyaluronic acid and hyaluronidase (HYAL1) in head and neck tumors". International Journal of Cancer. 106 (3): 438–45. doi:10.1002/ijc.11252. PMID 12845686. S2CID 21964172.

- Christopoulos TA, Papageorgakopoulou N, Theocharis DA, Mastronikolis NS, Papadas TA, Vynios DH (July 2006). "Hyaluronidase and CD44 hyaluronan receptor expression in squamous cell laryngeal carcinoma". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 1760 (7): 1039–45. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.03.019. PMID 16713680.

- Lokeshwar VB, Estrella V, Lopez L, Kramer M, Gomez P, Soloway MS, Lokeshwar BL (December 2006). "HYAL1-v1, an alternatively spliced variant of HYAL1 hyaluronidase: a negative regulator of bladder cancer". Cancer Research. 66 (23): 11219–27. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1121. PMID 17145867.

- Hofinger ES, Spickenreither M, Oschmann J, Bernhardt G, Rudolph R, Buschauer A (April 2007). "Recombinant human hyaluronidase Hyal-1: insect cells versus Escherichia coli as expression system and identification of low molecular weight inhibitors". Glycobiology. 17 (4): 444–53. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.533.3476. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwm003. PMID 17227790.

- Nieuwdorp M, Holleman F, de Groot E, Vink H, Gort J, Kontush A, Chapman MJ, Hutten BA, Brouwer CB, Hoekstra JB, Kastelein JJ, Stroes ES (June 2007). "Perturbation of hyaluronan metabolism predisposes patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus to atherosclerosis". Diabetologia. 50 (6): 1288–93. doi:10.1007/s00125-007-0666-4. PMC 1914278. PMID 17415544.

- Bharadwaj AG, Rector K, Simpson MA (July 2007). "Inducible hyaluronan production reveals differential effects on prostate tumor cell growth and tumor angiogenesis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (28): 20561–72. doi:10.1074/jbc.M702964200. PMID 17502371. S2CID 25576031.