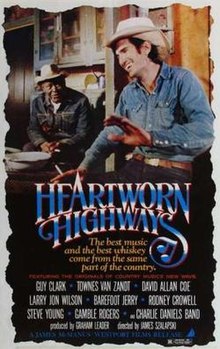

Heartworn Highways is a documentary film by James Szalapski whose vision captured some of the founders of the Outlaw Country movement in Texas and Tennessee in the last weeks of 1975 and the first weeks of 1976.[1] The film was not released theatrically until 1981.[1] It has since gained cult status amongst fans of the genre.[2]

| Heartworn Highways | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | James Szalapski |

| Written by | James Szalapski |

| Produced by | Graham Leader |

| Starring | Guy Clark Townes Van Zandt Steve Earle David Allan Coe Rodney Crowell Gamble Rogers Steve Young The Charlie Daniels Band Larry Jon Wilson |

| Cinematography | James Szalapski |

| Edited by | Phillip Schopper |

| Distributed by | First Run Features (theatrical) Navarre Corporation (DVD) Warner Bros. Domestic Cable Distribution |

Release date |

|

Running time | 92 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Plot

editThe documentary covers singer-songwriters whose songs are more traditional to early folk and country music instead of following in the tradition of the previous generation. Some of film's featured performers are Guy Clark, Townes Van Zandt, Steve Earle, David Allan Coe, Rodney Crowell, Gamble Rogers, Steve Young, and The Charlie Daniels Band. The movie features the first known recordings of Grammy award winners Steve Earle and Rodney Crowell who were quite young at the time and appear to be students of mentor Guy Clark. Steve Earle was also a big fan of Van Zandt at the time.

The beginning of the movie shows Larry Jon Wilson in a recording studio, awakened for the movie after an evening of post-gig debauchery. The filmmaker goes to Austin and visits Townes Van Zandt at his trailer (at what is now 11th and Charlotte in the Clarksville neighborhood of downtown Austin) and his girlfriend Cindy, his dog Geraldine, Rex "Wrecks" Bell, and Uncle Seymour Washington at the home of Washington, who is also called "The Walking Blacksmith," and who gives his great worldly advice to the viewers and represents a very important aspect of the atmosphere that these songwriters living in the South are surrounded by and involved in.

The movie shows Charlie Daniels completely fill a big high school gymnasium. Then the camera man, sound recorder and director join David Allan Coe and film him playing a gig at the Tennessee State Prison where he admits to being a former inmate and tells a story of being there and seems to bring out friends of his onto the stage who still are inmates there and they perform a gospel number "Thank You Jesus" that they used to sing in the yard. The end of the movie shows a drinking party that starts Christmas Eve and ends sometime Christmas Day at Guy Clark's house in Nashville with Guy, Susanna Clark, Steve Young, Rodney Crowell, Steve Earle, Jim McGuire (playing the dobro), along with several other guests. Steve Young leads the group in a rendition of Hank Williams' song "I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry" and Rodney Crowell leads everyone in "Silent Night".

Reception

editThis section contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (September 2022) |

Pauline Kael wrote highly of the film and its lyricism, but lamented the loose structure and lack of contextualizing information:

Szalapski is an attentive and scrupulous cinematographer; he loves his subjects, and the imagery is so warm and finely detailed that I had a hard time believing I was seeing a blow-up from 16-mm. But in this film he isn't yet a director—not fully, anyway ... It's fairly clear that during the (underfinanced) shooting he caught whatever he could; he couldn't plan a structure, and he probably wasn't looking for anything as vulgar as a hook or an angle. Which is too bad, because although there is very little in the film that isn't friendly or funny or really soul-stirring, it has no unifying energy. Watching it is like being carted off to a good party by people who told you where they were taking you so casually that the names of the people who were going to be there didn't sink in.[3]

Janet Maslin also noted the unfocused ambience:

The camera periodically (and somewhat unpredictably) drops in on a tavern where the regulars play pool and grouse about what country music is coming to. A woman is seen singing here - a homely elderly woman with long teased hair, a too-tight shimmering jumpsuit and a voice not even Smith or Wesson could admire. The movie presents her almost matter-of-factly, though, or at least it offers no discernible attitude toward her. Here, as in many places, the directorial haziness becomes a problem. But for those interested in the particular performers to whom the film is devoted, Heartworn Highways at least offers ambience, if not much more.[4]

Contemporary critics, such as Doug Freeman, see the lack of structure as a strength:

Yet in many ways, Heartworn Highways refuses that historicizing assessment, even resists it. The film would certainly not have become the canonical documentary it has without the subsequent success of its subjects, but their names are never the emphasis here. While the songwriters Szalapski follows are exceptional, there is the sense that he could have just as effectively been following any number of other young artists or communities. The documentary pushes into the moment, which if not timeless, is at least removed from time. The lack of context as the camera rolls is the point.[5]

Music

editSongs performed in the documentary:

- Guy Clark - "L.A. Freeway"

- Larry Jon Wilson - "Ohoopee River Bottomland"

- David Allan Coe - "Keep on Trucking"

- Big Mack McGowan & Glenn Stagner "The Doctor's Blues"

- Guy Clark - "That Old Time Feeling"

- Townes Van Zandt - "Waitin' Around to Die"[6]

- David Allan Coe - "I Still Sing the Old Songs"

- Barefoot Jerry - "Two Mile Pike"

- Rodney Crowell - "Bluebird Wine"

- Steve Young - "Alabama Highway"

- Guy Clark - "Texas Cooking"

- Gamble Rogers - "Black Label Blues"

- Peggy Brooks - "Lets Go All the Way"

- The Charlie Daniels Band - "Texas"

- David Allan Coe - "Penitentiary Blues"

- David Allan Coe - "River"

- Steve Earle - "Elijah's Church" (partial)

- Ensemble - "Silent Night"

"Extras" (bonus songs on the DVD):

- Guy Clark - "Desperadoes Waiting for a Train"

- Townes Van Zandt - "Pancho & Lefty"

- Richard Dobson - "Hard by the Highway"

- The Charlie Daniels Band - "Long Haired Country Boy"

- Guy Clark w/ Rodney Crowell - "Ballad of Laverne and Captain Flint"

- John Hiatt - "One for the One for Me"

- Steve Earle - "Darlin' Commit Me"

- David Allan Coe - "Thank You, Jesus"

Party at Guy Clark's house:

- Steve Earle - "Mercenary Song"

- Rodney Crowell - "Young Girls Hungry Smile"

- Richard Dobson - "Forever, for Always, for Certain"

- Billy Callery - "Question"

- Steve Young - "I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry"

- Steve Earle & Rodney Crowell - "Stay a Little Longer"

- Guy Clark - "Country Morning Music"

References

edit- ^ a b AllMovie entry for Heartworn Highways.

- ^ ROCKUARY 2019 - Spectacle Theater

- ^ Kael, Pauline (1984). Taking It All In. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. p. 204. ISBN 0030693616.

- ^ New York Times, May 14, 1981, Section C, Page 28 of the National edition with the headline: COUNTRY MUSICIANS RIDE 'HEARTWORN HIGHWAY', by Janet Maslin

- ^ Heartworn Highways, 1976, NR, 92 min. Directed by James Szalapski. REVIEWED By Doug Freeman, Fri., Feb. 5, 2021, online.

- ^ HEARTWORN HIGHWAYS (James Szalapski, 1976) on Vimeo

External links

edit- Heartworn Highways at IMDb

- Heartworn Highways at AllMovie

- Heartworn Highways at Rotten Tomatoes

- Official re-release trailer

- Heartworn Highways Revisited at IMDb produced in 2015