The 56-mile (90 km) High Road to Taos is a scenic, winding road through the Sangre de Cristo Mountains between Santa Fe and Taos. (The "Low Road" runs through the valleys along the Rio Grande). It winds through high desert, mountains, forests, small farms, and tiny Spanish land grant villages and Pueblo Indian villages. Scattered along the way are the galleries and studios of traditional artisans and artists drawn by the natural beauty. It has been recognized by the state of New Mexico as an official scenic byway.[2]

| High Road to Taos | |

|---|---|

Truchas, with Truchas Peaks in background | |

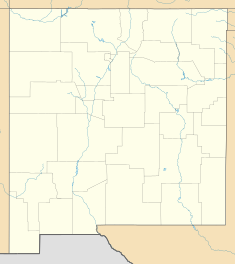

| Location | New Mexico |

| Coordinates | 35°53′49″N 106°1′12″W / 35.89694°N 106.02000°W |

| Designated | February 28, 1975[1] |

| Reference no. | 363 |

Description

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

Nambé

editThe High Road to Taos Scenic Byway begins north of Santa Fe in Pojoaque, New Mexico, at the intersection of U.S. 285/84 and State Road 503. It continues along State Road 503 to Nambé Pueblo. Founded in the 14th century, Nambé means "People of the Round Earth" in Tewa, their native language.[3]

The pueblo plaza is a registered National Historic Landmark. The church on State Road 503 is not original; ill-considered efforts to restore the grand original church caused it to collapse. The pueblo encompasses 19,000 acres (77 km2) of land with waterfalls, lakes, and mountainous areas.[4] Until about 1830, Nambe was known for a pottery style called Nambe Polychrome. Today, pottery is making a comeback, especially black-on-black and red-on-white. Weaving is also reemerging.[citation needed]

Chimayó

editThe road continues through the rolling hills and wind-carved hoodoos of the badlands. At 7.5 miles (12.1 km), the High Road turns left onto State Road 98 (Juan Medina Road), which continues across the open, rolling high desert until it dips down to the green, farming valley of Chimayó. Visitors often stop at the historic Santuario de Chimayó.

Built between 1811–16, this tiny church is visited by pilgrims from all over the United States and old Mexico, especially on Good Friday of Easter week, when crowds swell to the thousands. A little farther on is the Rancho de Chimayó Restaurant, housed in a historic adobe building. Chimayó also has many traditional weaving studios owned by descendants of the original Spanish settlers.

Córdova

editWhere State Road 98 dead-ends, the road turns right onto State Road 76 and begins the climb into the Sangre de Cristo Mountains and the little villages of the High Road. First is Córdova, a collection of narrow streets above a river valley, accessible via a road on the right. Córdova is known for its traditional woodcarvers, such as George López, who carve santos (saints) in the "Córdova Style": unpainted but elaborately carved and featuring the distinctive grain and shape of the wood. A very short drive takes you into the village and back to State Road 76.

Truchas

editThe road continues to climb to the top of a high mesa and the village of Truchas, meaning 'trout', a scattering of adobe houses backed by the snow-capped Truchas Peaks. (The High Road and State Road 76 turn left, but much of the village is straight ahead on State Road 75.) This Hispanic farming community once furnished the set for the movie version of the John Nichols novel The Milagro Beanfield War. Truchas was established by a royal land grant in 1754 to create a buffer against nomadic Apache and Comanche bands who often raided both Spanish villages and Native American pueblos.[5]

Hence, it was built as a walled compound around a plaza. Its settlers hand-dug miles of acequias (irrigation ditches) to bring water from the trout-filled river that gave the town its name.[citation needed] Although today's residents still work their farms, many commute to jobs in Santa Fe or Los Alamos. A few still make their living as traditional craftspeople alongside the many European-American artists and galleries that have been drawn to Truchas's mountain views.[citation needed]

Ojo Sarco

editThe High Road continues along State Road 76 through the former Las Trampas Land Grant, now the Carson National Forest to a series of very small villages. First is Ojo Sarco, believed to be named for a spring in a nearby cañada (glen). The name was sometimes spelled Ojo Zarco; ojo is now translated as "eye" in Spanish, but also used to mean "spring" and zarco means "light blue", hence "blue spring".

Las Trampas

editNext is Las Trampas, founded in 1751 by a royal land grant, "Santo Tomás Apostol del Río de las Trampas" ("Saint Thomas, Apostle of the River of Traps").[6]

Despite the heavy toll taken by a smallpox epidemic and raids by Plains Indians, the village of Las Trampas survived and the settlers managed to build the stately San José de Gracia Church, completed in 1776.[7] It is a National Historic Landmark, and the village is a National Historic District. The building across from the church with the little bell tower was the school.[citation needed]

El Valle and Ojito

editState Road 76 continues through the Carson National Forest. Smaller roads lead off to El Valle or 'the valley' and Ojito 'little spring', both settled by colonists from Las Trampas. Both are accessed by scenic drives through the forest.

Chamisal

editThe next village on SR 76 is Chamisal. It, too, was settled by Spanish villagers moving out from Las Trampas; all of these villages lie within the Las Trampas land grant. Chamisal is probably named for the "chamisa" shrub (Chrysothamnus, or rabbitbrush) which turns golden in late summer. Chamisal Creek flows northwest to join the Peñasco River. There is a small, old church in the village (follow the sign to the old plaza).

Picurís

editWhen SR 76 ends at a stop sign, the High Road turns right onto State Road 75. However, turn left to visit Picurís Pueblo. Spanish explorer Don Juan de Oñate called these people "pikuria"—those who paint.[8]

Before the Spanish came, Picurís was one of the largest and most powerful of the pueblos, located at the confluence of two rivers and on a major pass that leads through the mountains to the Great Plains in the east. This strategic location made it a key site for trade with the Apaches, but once the Comanches arrived and the Spanish brought horses, the pueblo became vulnerable to attack.

The fierce Picurís continued to fight the Spanish even after the Reconquest, and lost many members of the tribe as a result.[5] Like Taos Pueblo, Picurís is a Tiwa pueblo. Picurís today, while small, has a thriving buffalo herd and runs a hotel in Santa Fe. It is known for its gold-hued micaceous pottery (featuring flecks of shiny mica). When the 200-year-old San Lorenzo de Picurís church collapsed in 1989 due to water damage, pueblo members rebuilt it by hand. San Lorenzo Feast Day is August 10. (Tribal members request that visitors get permission before taking photos anywhere on the pueblo.)

Peñasco

editThe High Road continues on State Road 75 into Peñasco. The villages of Llano San Juan, Llano Largo, and Santa Barbara in the Peñasco area were first settled by Spanish colonists in 1796, the same year as Taos. Today the town of Peñasco serves residents in the many villages and rural areas surrounding it, as well as the residents of Picurís Pueblo.

Llano San Juan and Llano de la Yegua

editLeaving Peñasco, the High Road and State Road 75 make a wide curve to the left. Going straight onto State Road 73 offers a side trip into Llano San Juan and Llano de la Yegua. A llano is a "broad, treeless plain," while yegua means mare. These are lush, green valleys flanked by steep mesas. The small hamlet of Llano San Juan is served by the San Juan Nepomuceno Catholic Church.[9]

Vadito

editThe High Road continues along State Road 75 through the tiny village of Vadito, which means "little ford." Beyond Vadito, the road passes through the valley of Placita.

Sipapu

editAt the "stone wall" intersection, the High Road turns left onto State Road 518 to Ranchos de Taos. However, just a few miles east on SR 518 is Sipapu Ski Resort and Recreation Area. The drive to Sipapu through the Carson National Forest is very scenic, and there are numerous trails and fishing spots on the Rio Pueblo.

Talpa

editThe High Road turns northwest along SR 518 and passes through more valleys and vistas of the Carson National Forest. Eventually it reaches Talpa, the last High Road village. Talpa is an ancient site; pit houses and pueblos were built here from 1100 to 1300. It was settled by Spanish colonists in the early 18th century, about the same time as Taos. Talpa, which means "knob", may refer to a formation in one of Talpa's little canyons.

Ranchos de Taos

editAlthough the High Road officially ends where SR 518 meets SR 68 in Ranchos de Taos, symbolically it ends at the famous San Francisco de Asis Mission Church a few blocks south. This is probably one of the most painted and photographed churches in the nation—especially the buttresses in the back, famously painted by Georgia O'Keeffe and photographed by Paul Strand and Ansel Adams. Completion of its construction took from 1772 to 1815.

Location

editBeginning: 35°53′49″N 106°01′12″W / 35.897°N 106.020°W End: 36°21′29″N 105°36′29″W / 36.358°N 105.608°W

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "New Mexico State and National Registers". New Mexico Historic Preservation Commission. Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- ^ Frantz, Laurie, The High Road to Taos, New Mexico Tourism Department, archived from the original on 2009-08-04, retrieved 2009-08-26

- ^ New Mexico Office of the State Historian, Nambe Pueblo, archived from the original on 2010-10-06, retrieved 2009-08-26

- ^ About Nambe Pueblo, archived from the original on 2009-06-14, retrieved 2009-08-26

- ^ a b deBuys, William (1985), Enchantment and Exploitation: The Life and Hard Times of a New Mexico Mountain Range, Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press

- ^ New Mexico Office of the State Historian, Las Trampas Grant, archived from the original on 2010-10-11, retrieved 2009-08-26

- ^ Lux, Annie (2007), Historic New Mexico Churches, Salt Lake City, UT: Gibbs Smith

- ^ New Mexico Office of the State Historian, Las Trampas Grant, archived from the original on 2010-10-07, retrieved 2009-08-26

- ^ Lux, Annie (2007). Historic New Mexico Churches. Salt Lake City, Utah: Gibbs Smith. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-4236-0169-2.