The Hondo Group is a group of geologic formations that crops out in most of the Precambrian-cored uplifts of northern New Mexico. Detrital zircon geochronology gives a maximum age for the lower Hondo Group of 1765 to 1704 million years (Mya), corresponding to the Statherian period.

| Hondo Group | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: | |

Hondo Group (Ortega Formation) in the Tusas Mountains, New Mexico | |

| Type | Group |

| Sub-units | Ortega Formation, Rinconada Formation |

| Underlies | Pilar Formation |

| Overlies | Vadito Group |

| Thickness | 2,200 m (7,200 ft) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Metasedimentary rock |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 36°14′46″N 105°44′42″W / 36.246°N 105.745°W |

| Region | Picuris Mountains, New Mexico |

| Country | United States |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Hondo Canyon |

| Named by | Bauer and Williams |

| Year defined | 1989 |

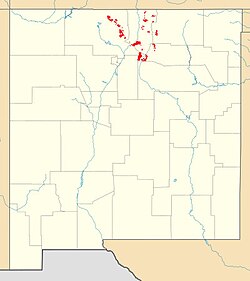

Map of Hondo Group outcrops | |

Geology

editThe Hondo Group consists of a lower very clean quartzite (the Ortega Formation) and upper schists, quartzites, and slates. The total thickness is about 2,200 meters (7,200 feet).[1] The upper section is absent in the Tusas Mountains, where the Hondo Group is essentially synonymous with the Ortega Formation. The upper section is assigned to the Rinconada Formation in the Picuris Mountains. The most complete section is in the northern Picuris Mountains, where the Hondo Group fills an overturned syncline.[2] Detrital zircon geochronology establishes an age for the lower Hondo Group of 1765 to 1704 Mya.[3]

The Pilar and Piedra Lumbre Formations were originally included in the Hondo Group. However, a metamorphosed tuff bed in the Pilar Formation yields an age of 1488 ± 6 Mya, considerably younger than the Ortega Quartzite. The Piedra Lumbre Formation likewise contains zircons dated to 1425 Mya. This suggests that the Pilar Formation and Piedra Lumbre Formation should be removed from the Hondo Group, and provides evidence supporting the Picuris orogeny.[4]

The Hondo Group lies structurally below the Vadito Group in the Picuris Mountains. However, both groups have been severely deformed and metamorphosed, and the Vadito Group is thought to actually be the older of the two groups. Cross-bedding indicates that the Vadito Group has been overturned.[5] The contact between the two groups is fairly easy to trace using a regional manganese-rich marker bed in the uppermost Vadito Group,[2] which may have formed by syngenetic deposition from hydrothermal fluids, or a more general manganese enrichment of basin waters at the close of Vadito volcanism. Another possibility is that it is a weathering horizon. Either possibility would make it an important regional time marker.[6]

The group is interpreted as fluvial to shallow marine deposition on a southward-dipping siliciclastic shelf. Together, the Vadito Group and lower Hondo Group likely represent deposition in a back-arc basin associated with the Yavapai orogeny, named the Pilar basin.[3]

Economic geology

editGold, silver, and oxidized copper minerals were discovered on Copper Hill around 1900 and prospected over the next five years. The ore minerals were concentrated along the contact between the Ortega and Rinconada Formations. Mining began along the Champion vein on the west side of the hill, with two shaft connected by an adit 100 meters (330 feet) long. However, the mine was unsuccessful. Renewed exploratory drilling in 1982 determined that the deposits are presently uneconomical to mine.[7]

History of investigation

editThe unit was originally designated as the Ortega Group by Long in 1976, but this caused confusion with the Ortega Formation. The name, Hondo Group, was proposed by Bauer and Williams in 1989 as part of their sweeping revision of the Precambrian stratigraphy of northern New Mexico.[2]

Footnotes

editReferences

edit- Bauer, Paul W. (2004). "Proterozoic rocks of the Pilar Cliffs, Picuris Mountains, New Mexico" (PDF). New Mexico Geological Society Field Conference Series. 55: 193–205. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- Bauer, Paul W.; Williams, Michael L. (August 1989). "Stratigraphic nomenclature ol proterozoic rocks, northern New Mexico-revisions, redefinitions, and formalization" (PDF). New Mexico Geology. 11 (3). Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- Daniel, Christopher G.; Pfeifer, Lily S.; Jones, James V III; McFarlane, Christopher M. (2013). "Detrital zircon evidence for non-Laurentian provenance, Mesoproterozoic (ca. 1490–1450 Ma) deposition and orogenesis in a reconstructed orogenic belt, northern New Mexico, USA: Defining the Picuris orogeny". GSA Bulletin. 125 (9–10): 1423–1441. doi:10.1130/B30804.1. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- Jones, James V. III; Daniel, Christopher G.; Frei, Dirk; Thrane, Kristine (2011). "Revised regional correlations and tectonic implications of Paleoproterozoic and Mesoproterozoic metasedimentary rocks in northern New Mexico, USA: New findings from detrital zircon studies of the Hondo Group, Vadito Group, and Marqueñas Formation". Geosphere. 7 (4): 974–991. doi:10.1130/GES00614.1. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- Montgomery, Arthur (1953). "PreCambrian Geology of the Picuris Range, northcentral New Mexico" (PDF). State Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources Bulletins. 30.

- Williams, M.L. (1987). Stratigraphic, structural, and metamorphic relationships in Proterozoic rocks from northern New Mexico [Ph.D. dissertation]:. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico.

- Williams, Michael L.; Bauer, Paul W. (1 November 1995). "The Copper Hill Cu-Ag-Sb deposit, Picuris Range, New Mexico; retrograde mineralization in a brittle-ductile trap". Economic Geology. 90 (7): 1994–2005. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.90.7.1994.