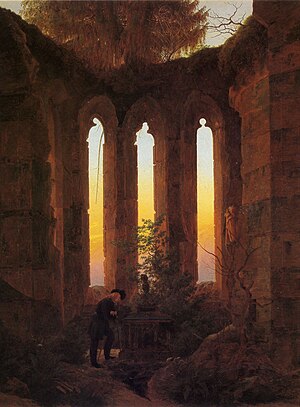

Hutten's Grave (1823) is an oil on canvas painting by Caspar David Friedrich, showing a man in Lützow Free Corps uniform standing by the grave of the Renaissance humanist and German nationalist Ulrich von Hutten.[1] Influenced heavily by the political climate of the time and Friedrich's own political beliefs, the painting is one of Friedrich's most political works and affirms his allegiance to the German nationalist movement. The painting was made to commemorate the 300th anniversary of Hutten's death and the 10th anniversary of Napoleon's invasion of Germany.[2] It is now in the Klassik Stiftung Weimar's collection and on show in the Schlossmuseum at the Stadtschloss Weimar.

| Hutten's Grave | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Caspar David Friedrich |

| Year | 1823 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 73 cm × 93 cm (29 in × 37 in) |

| Location | Klassik Stiftung Weimar, Weimar |

Background

editFollowing the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Leipzig in 1813, the ideas of German unification and nationalism gained momentum. The center of new liberal ideas was the universities. However, these ideas troubled the ruling elite and the new order established by the Congress of Vienna (1814-1815). As a result, the members of the German Confederation instituted the Carlsbad Decrees in 1819, which severely limited free speech and banned the teaching of liberal ideas in universities.[3] Friedrich saw these developments as a betrayal of the spirit of those who had fought against Napoleon.[3] He wanted to create a work that would honor liberal ideas and serve as a monument to those who had died in pursuit of them.[3]

Composition and symbolism

editIn this work, Friedrich combines the political and religious in an overt manner that is unlike many of his previous works. The gothic ruin that serves as the setting for the image is based on a monastery in the German city of Oybin. The man in the image is wearing altdeutsch (old German) attire which grew popular during Napoleon's campaign as a symbol of anti-French sentiment.[4] The style was also adopted by the Lützow Free Corps. Those who viewed the image at the time would have recognized this style and its political meaning.[4] Friedrich's decision to depict the grave of Ulrich von Hutten was also political. Hutten was a German nationalist and a contemporary of Martin Luther. These values were very important to Friedrich, who wanted German unity and was a devout Lutheran himself. Several names and years are inscribed on the tomb: "Jahn 1813," "Arndt 1813," "Stein 1813," "Görres 1821," and "Scharnhorst."[5]: 98 All of these men were contemporaries of Friedrich and all were German nationalist thinkers. Scharnhorst died in the Battle of Leipzig and the rest faced persecution and even exile for spreading liberal ideas. By combining the tomb of Hutten with the names of contemporary nationalist thinkers Friedrich linked together the past and present of German nationalist thinking. He also called attention to the repression of liberal ideas and what he saw as the failure of the regional elite to embrace reforms.[5]

Friedrich incorporates religious symbols with the political message. The most apparent is the headless statue of Faith in the background.[6] Scholar have interpreted the figure as a symbol of mourning and as reference to the falling importance of religion.[6] Other symbols that further emphasize the sense of death are the tomb and the dead tree in the foreground. The lancet windows have been interpreted to represent the outlines of Saints watching over both the tomb and man.[7] Some scholars have pointed to the separation between the inside and outside of the ruin as representing the difference between Catholicism and Lutheranism respectively.[7] The inside shows the old Catholic order as broken, while the expanse of the outside world, representing Lutheranism, gives a sense of freedom and hope.[7]

Strictly speaking, the figure in the image is not an example of a Rückenfigur; instead of being fully turned, he is half turned so that we are able to see his face. But the man functions in much the same way as a fully turned Rückenfigur, inviting subjective identification. The man here represents what Joseph Koerner has described as a "missed encounter with history" in which the future of German reunification can only be imagined through an unresolved relationship with the past.[8]: 244

Related works

edit- Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818)

- In this image, the main figure is also wearing altdeutsch attire, which is also meant to allude to his military experience and German heritage.

- Two Men Contemplating the Moon (1819-1820)

- Here two figures also in altdeutsch attire stand looking at the moon. This image is also widely seen as being a political critique of the repressive government following the Congress of Vienna.[9]

- Ruins at Oybin (1812)

- Friedrich reused the setting in this image for the setting in Hutten's Grave.

-

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818)

-

Two Men Contemplating the Moon (1819-1820)

-

Ruins at Oybin (1812)

Sale

editWith the original sale of the work in 1826 all proceeds went to support the Greek War of Independence.[10] The work was purchased by Karl August, Duke of Saxe-Weimar.[10]

Legacy

editHutten's Grave and Friedrich's other works related to German nationalism and heritage were later coopted by the Nazis to promote their ideology.[11] The Nazis highlighted the elements of nationalism, German unification, and sacrifice. This association tainted Friedrich's reputation and required decades of scholarship to resurrect his reputation.[citation needed]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ (in German) Helmut Börsch-Supan, Karl Wilhelm Jähnig: Caspar David Friedrich. Gemälde, Druckgraphik und bildmäßige Zeichnungen, Prestel Verlag, München 1973, ISBN 3-7913-0053-9

- ^ Koerner, Joseph Leo; Friedrich, Caspar David (1990). Caspar David Friedrich and the subject of landscape. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press. pp. 243–244. ISBN 978-0-300-04926-8.

- ^ a b c Koerner, Joseph Leo; Friedrich, Caspar David (1990). Caspar David Friedrich and the subject of landscape. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press. pp. 243–244. ISBN 978-0-300-04926-8.

- ^ a b Koerner, Joseph Leo; Friedrich, Caspar David (1990). Caspar David Friedrich and the subject of landscape. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press. pp. 243–244. ISBN 978-0-300-04926-8.

- ^ a b Hofmann, Werner; Friedrich, Caspar David; Whittall, Mary; Hofmann, Werner (2000). Caspar David Friedrich. New York: Thames & Hudson. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-500-09295-8.

- ^ a b Vaughan, William; Friedrich, Caspar David; Börsch-Supan, Helmut; Neidhardt, Hans Joachim; Tate Gallery, eds. (1972). Caspar David Friedrich, 1774-1840: romantic landscape painting in Dresden (2. impr ed.). London: Tate Gallery. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-900874-35-2.

- ^ a b c Hofmann, Werner; Friedrich, Caspar David; Whittall, Mary; Hofmann, Werner (2000). Caspar David Friedrich. New York: Thames & Hudson. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-500-09295-8.

- ^ Koerner, Joseph Leo; Friedrich, Caspar David (1990). Caspar David Friedrich and the subject of landscape. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press. pp. 243–244. ISBN 978-0-300-04926-8.

- ^ Wolf, Norbert; Friedrich, Caspar David (2018). Caspar David Friedrich: 1774-1840: the painter of stillness. Basic art series 2.0. Köln: TASCHEN. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-3-8365-6071-9.

- ^ a b Hofmann, Werner; Friedrich, Caspar David; Whittall, Mary; Hofmann, Werner (2000). Caspar David Friedrich. New York: Thames & Hudson. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-500-09295-8.

- ^ Koerner, Joseph Leo; Friedrich, Caspar David (1990). Caspar David Friedrich and the subject of landscape. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press. pp. 243–244. ISBN 978-0-300-04926-8.