Gondi (Gōṇḍī), natively known as Koitur (Kōī, Kōītōr), is a South-Central Dravidian language, spoken by about three million Gondi people,[2] chiefly in the Indian states of Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and by small minorities in neighbouring states. Although it is the language of the Gond people, it is highly endangered, with only one fifth of Gonds speaking the language. Gondi has a rich folk literature, examples of which are wedding songs and narrations. Gondi people are ethnically related to the Telugus.

| Gondi | |

|---|---|

| गोण्डि, గోణ్డి | |

| Native to | India |

| Region | Gondwana |

| Ethnicity | Gondi |

Native speakers | 2.98 million (2011 census)[1] |

Dravidian

| |

| Telugu script, Devanagari, Odia script, Gunjala script, Masaram script (See Gondi scripts) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | gon |

| ISO 639-3 | gon – inclusive codeIndividual codes: gno – Northern Gondiesg – Aheri Gondiwsg – Adilabad Gondi |

| Glottolog | nort3258 |

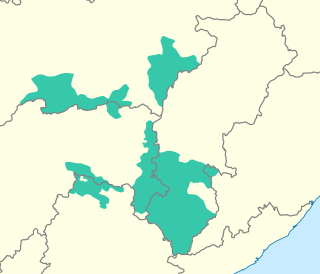

Areas where Gondi is spoken. Koya not included. | |

Gondi is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

| Person | Gōṇḍ |

|---|---|

| People | Gōṇḍir |

| Language | Gōṇḍī, Kōī, Kōītōr |

| Country | Gōṇḍvana |

Endangerment

editAlthough almost 13 million people returned themselves as Gonds on the 2011 census, however only 2.98 million recorded themselves as speakers of Gondi. In the present-day, large communities of Gondi speakers can be found in southeastern Madhya Pradesh (Betul, Chhindwara, Seoni, Balaghat, Mandla, Dindori and Jabalpur districts), eastern Maharashtra (Amravati, Nagpur, Yavatmal, Chandrapur, Gadchiroli and Gondia districts), northern Telangana (Adilabad, Komaram Bheem, and Bhadradi Kothagudem districts), Bastar division of Chhattisgarh and Nabarangpur district of Odisha.[1]

This is the result of a language shift from Gondi to regional languages in the majority of the Gondi population, especially those in the northern portion of their range. By the 1920s, half of Gonds had stopped speaking the language entirely.[3] The language is under severe stress from dominant languages such as Hindi, Chhattisgarhi, Marathi and Odia due to their use in education and employment. In order to improve their situation, Gond households adopt the more prestigious dominant language and their children become monolingual in that language. Already in the 1970s, Gondi youth in places with increased contact with wider society had stopped speaking the language, seeing it as a relic of old times.[4] The constant contact between speakers of Gondi and Indo-Aryan languages has resulted in massive Indo-Aryan borrowing in Gondi, found in vocabulary, grammar and syntax. In one survey in Anuppur district for instance, it was found the dialect of Gondi spoken there, known as dehati bhasha ('rural language'), was actually a mixture of Hindi and Chhattisgarhi rather than Gondi. However, the survey also found younger Gonds had a positive attitude towards speaking Gondi and saving the language from extinction.[5] Another survey from areas throughout the Gond region found younger Gonds felt developing their mother tongue was less important, but there were still large numbers willing to help in its development. Some attempts at revitalization have included children's books and online videos.[6]

Etymology

editThe origin of the name Gond, used by outsiders, is still uncertain. Some believe the word to derive from the Dravidian kond, meaning hill, similar to the Khonds of Odisha.[7]

Another theory, according to Vol. 3 of the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life, is that the name was given to them by the Mughal dynasty of the 16th–18th centuries. It was the Mughals who first used the term "Gond", meaning "hill people", to refer to the group.[8]

The Gonds call themselves Koitur (Kōītōr) or Koi (Kōī), which also has no definitive origin.[citation needed]

Characteristics

editGondi has a two-gender system, substantives being either masculine or nonmasculine.[citation needed] Gondi has developed aspirated stops, distancing itself from its ancestor Proto-Dravidian.[citation needed]

Phonology

editConsonants

edit| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Retroflex | Post-alv./ Palatal |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | (ɳ) | (ɲ) | ŋ | ||

| Stop/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | ʈ | tʃ | k | |

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | ʈʰ | tʃʰ | kʰ | ||

| voiced | b | d | ɖ | dʒ | ɡ | ||

| breathy | bʱ | dʱ | ɖʱ | dʒʱ | ɡʱ | ||

| Fricative | v | s | (ʂ) | h | |||

| Approx. | central | (w) | j | ||||

| lateral | l | ||||||

| Tap | ɾ | ɽ | |||||

- Sounds /tʃ tʃʰ dʒ dʒʱ/ can be heard as alveo-palatal [tɕ tɕʰ dʑ dʑʱ] before non-front vowels in some dialects.

- /s/ is realized as a retroflex sibilant [ʂ] before a retroflex stop /ʈ/.

- An alveolar tap sound /ɾ/ can vary freely with a trill sound [r].

- /n/ is realized as a dental nasal [n̪] before a dental stop sound, a palatal nasal [ɲ] before a palatal affricate, and a retroflex nasal [ɳ] before a retroflex stop. Elsewhere, it is articulated as an alveolar nasal [n].

- /v/ is realized as an approximant [w] when occurring before rounded vowels.[9]

- All consonants except /ɽ, ɾ, s, h/ can occur either double or single in the medial position.

- In south and southeastern Gondi dialects, the initial s is turning into h and getting deleted for some.[10]

- Hill-Maṛia dialect of Gondi has a uvular /ʁ/ which corresponds to the r̠ in other Dravidian languages or *t̠ from proto Dravidian and it contrasts with the alveolar r corresponding to proto-Dravidian *r.[10]

Vowels

edit| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| High | i | iː | u | uː | ||

| Mid | e | eː | o | oː | ||

| Low | a | aː | ||||

Morphology

editNouns

editGondi has derivative suffixes to denote gender for certain special words: -a:l and -o:r for masculine, and -a:r for feminine. Plural suffixes are also divided into masculine and feminine, -r is used for most masculine nouns, -ir ends masculine nouns ending in -e, and -ur ends nouns ending in -o or -or. For instance:[9]

kānḍī - boy kānḍīr - boys

kallē - thief kallīr - thieves

tottōr - ancestor tottūr - ancestors

are all masculine.

For non-masculine nouns, there are more suffixes: -n, -ik, -k, and a null suffix -ɸ

Before case markers are added, all nouns have an oblique marker. The oblique markers are -d-, -t-, -n-, -ṭ-, and -ɸ.

For instance:

kay-d-e: "in the hand"

Gondi has several case markers.[9]

Genitive case markers are -na, -va, -a.

- -na is used after na:r, meaning village. -va is used after personal and reflexive pronouns.

- -a is used elsewhere.

Sample text

editThe given sample text is Article 1 from the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[11]

English

editAll human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Northern Gondi

editसब् माने कुन् गौरव् अरु अधिकार् ना मांला ते जनंजात् सुतन्तर्ता अरु बराबर् ता हक् पुट्ताल। अवेन् भायि लेह्का माने मासि बेव्हार् कियाना आन्द।

Romanisation (ISO 15919)

editSab māne kun gaurav aru adhikār nā māmlā tē janamjāt sutantartā aru barābar tā hak puṭtāla. Aven bhāyi lehkā māne māsi bevhār kiyānā ānda.

Dialects

editMost of the Gondi dialects are still inadequately recorded and described. The more important dialects are Dorla, Koya, Madiya, Muria, and Raj Gond. Some basic phonologic features separate the northwestern dialects from the southeastern. One is the treatment of the original initial s, which is preserved in northern and western Gondi, while farther to the south and east it has been changed to h; in some other dialects it has been lost completely. Other dialectal variations in the Gondi language are the alteration of initial r with initial l and a change of e and o to a.

In 2015, the ISO 639 code for the "Southern Gondi language", "ggo", was deprecated and split into two codes, Aheri Gondi (esg) and Adilabad Gondi (wsg).[12][13]

Writing

editGondi writing can be split into two categories: that using its own writing systems and that using writing systems also used for other languages.

For lack of a widespread native script, Gondi is often written in Devanagari and Telugu scripts.

In 1928, Munshi Mangal Singh Masaram designed a native script based on Brahmi characters and in the same format of an Indian alphasyllabary. This script did not become widely used,[citation needed] although it is being encoded in Unicode.[14] Most Gonds remain illiterate.[citation needed]

A native script that dates up to 1750 has been discovered by a group of researchers from the University of Hyderabad. It's usually named Gunjala Gondi Lipi, after the place where it was found. According to Maharashtra Oriental Manuscripts Library and Research Centre of India, a dozen manuscripts were found in this script. Programs to create awareness and promotion of this script among the Gondi people are in development stage. The Gunjala Gondi Lipi has witnessed a surge in prominence, and well-supported efforts are being undertaken in villages of northern Andhra Pradesh to widen its usage.[citation needed]

References

edit- ^ a b "Census of India Website : Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India". www.censusindia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ Beine, David K. 1994. A Sociolinguistic Survey of the Gondi-speaking Communities of Central India. M.A. thesis. San Diego State University. chpt. 1

- ^ Russell, R. V. "The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India—Volume III". www.gutenberg.org. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- ^ Yadav, K. S. (1970). "Directed and Spontaneous Social Change: A Study of Gonds of Chhindwara". Economic and Political Weekly. 5 (11): 493–498. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 4359730.

- ^ Boruah, D. M. "Language Loss and Revitalization of Gondi language: An Endangered Language of Central India" (PDF). Language in India. 20 (9): 144–161. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ Mehta, Devansh; Santy, Sebastin; Mothilal, Ramaravind Kommiya; Srivastava, Brij Mohan Lal; Sharma, Alok; Shukla, Anurag; Prasad, Vishnu; U, Venkanna; Sharma, Amit; Bali, Kalika (26 January 2021). "Learnings from Technological Interventions in a Low Resource Language: A Case-Study on Gondi". arXiv:2004.10270 [cs.CL].

- ^ Arur, Sidharth; Wyeld, Theodor. "Exploring the Central India Art of the Gond People: contemporary materials and cultural significance" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Gonds – Document – Gale in Context: World History Archived 27 May 2023 at the Wayback Machine Gale, part of Cengage Group.

- ^ a b c Subrahmanyam, P. S. (1968). A descriptive grammar of Gondi. Annamalainagar, India: Annamalainagar: Annamalai Univ.

- ^ a b Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003). The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-43533-8. Archived from the original on 4 July 2023. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "मानेय अधिकार ता सार्वभैम घोषना" (PDF) (in Gondi).

- ^ "2015-062 | ISO 639-3". iso639-3.sil.org. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ Penny, Mark (24 August 2015). "ISO 639-3 Registration AuthorityRequest for Change toISO 639-3 Language CodeChange Request Number: 2015-062(completed by Registration authority)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ "Preliminary Proposal to Encode the Gondi Script in the UCS" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

Further reading

edit- Beine, David K. 1994. A Sociolinguistic Survey of the Gondi-speaking Communities of Central India. M.A. thesis. San Diego State University. 516 p.

- Chenevix Trench, Charles. Grammar of Gondi: As Spoken in the Betul District, Central Provinces, India; with Vocabulary, Folk-Tales, Stories and Songs of the Gonds / Volume 1 - Grammar. Madras: Government Press, 1919.

- Hivale, Shamrao, and Verrier Elwin. Songs of the Forest; The Folk Poetry of the Gonds. London: G. Allen & Unwin, ltd, 1935.

- Moss, Clement F. An Introduction to the Grammar of the Gondi Language. [Jubbalpore?]: Literature Committee of the Evangelical National Missionary Society of Sweden, 1950.

- Pagdi, Setumadhava Rao. A Grammar of the Gondi Language. [Hyderabad-Dn: s.n, 1954.

- Subrahmanyam, P. S. Descriptive Grammar of Gondi Annamalainagar: Annamalai University, 1968.