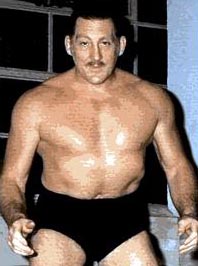

Karel Istaz[1][2] (August 3, 1924 – July 28, 2007), best known by his ring name Karl Gotch, was a Belgian professional wrestler, amateur wrestler, catch wrestler, and trainer.

| Karl Gotch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Karel Istaz[1][2] |

| Born | August 3, 1924[3] Antwerp, Belgium[4] |

| Died | July 28, 2007 (aged 82)[5] Tampa, Florida, U.S.[6] |

| Children | 1 |

| Professional wrestling career | |

| Ring name(s) | Karl Gotch[4] Karl Krauser[4] |

| Billed height | 6 ft 1 in (185 cm)[7] |

| Billed weight | 245 lb (111 kg)[7] |

| Billed from | Hamburg, Germany |

| Trained by | Billy Riley[4] The Snake Pit |

| Debut | 1950 |

| Retired | January 1, 1982[8] |

Gotch represented Belgium at the 1948 Summer Olympics in both freestyle and Greco-Roman wrestling before learning catch wrestling at Riley's Gym, better known as "The Snake Pit."[1][2] He was given the ringname "Gotch" by Ohio promoter Al Haft in honor of American wrestler Frank Gotch.[9] In Japan, he became known as a "God of Wrestling" (神様, Kamisama) alongside Billy Robinson and Lou Thesz, due to their collective influence on Japanese professional wrestling.[10][8]

Gotch had significantly influenced the development of modern mixed martial arts (MMA), especially in Japan. Several of Gotch's students, which included Satoru Sayama,[11] Masakatsu Funaki,[12][13] Minoru Suzuki[13][14] Akira Maeda,[15] and Nobuhiko Takada, established pioneering MMA promotions and training schools to transmit Gotch's training. These include Shooto and Pancrase, both of which predate the UFC, along with Fighting Network RINGS, and PRIDE, one of the most popular promotions of all time.[16][17][18][19][20]

Background

editIstaz was born in Antwerp, Belgium, where he excelled in amateur wrestling and represented Belgium at the 1948 Summer Olympics in both freestyle and Greco-Roman wrestling.[1][2][21] Gotch's life prior to the Olympics is unclear and has been subject to embellishment by pro wrestling magazines.[22] Gotch also trained in pehlwani, an Indian style of wrestling. This training led to Istaz's regime of calisthenic bodyweight exercise, which were used by wrestlers to build leg endurance and strength, such as the bridge, Hindu squats, and Hindu press ups.[23] Gotch's philosophy was later passed on to several of his students.

Professional wrestling career

editEurope and the United States

editIstaz's professional wrestling career began after training at Riley's Gym (later dubbed "The Snake Pit"), run by the renowned catch wrestler Billy Riley.[4] He debuted in 1950, wrestling throughout Europe under the ring name Karl Krauser, and winning titles including the German Heavyweight Championship and the European Championship.[4]

In the late 1950s, Istaz moved to the United States, and began wrestling as Karl Gotch.[4] In the United States, Gotch's wrestling style and lack of showmanship held him back, and he did not experience any great popularity at the time.[8] In 1961, he won the American Wrestling Alliance (Ohio) World Heavyweight Championship.[4] Gotch held the belt for two years before dropping the title to Lou Thesz, one of the few American wrestlers he respected because of the similarities of their styles (the two also share a German/Hungarian heritage). In 1962, Gotch was involved in a backstage altercation with the then-NWA World Heavyweight Champion "Nature Boy" Buddy Rogers, in which Rogers was injured.[8] The incident alienated Gotch from American promoters, and he began looking for work in Japan.[8]

He returned to the United States for a stint in the 1970s, with a brief run in the World Wide Wrestling Federation from August 1971 to February 1972. On December 6, 1971, he teamed with Rene Goulet to win the WWWF World Tag Team Championship from the inaugural champions, Luke Graham and Tarzan Tyler, in two straight falls of a best-two-out-of-three-falls match in Madison Square Garden.[8][24] They lost the championship on February 1, 1972, to Baron Mikel Scicluna and King Curtis.[8]

Japan

editDuring the 1960s, Gotch continued to travel. He wrestled in Australia as Karl Krauser, and in 1965 he defeated Spiros Arion to win the International Wrestling Alliance's Heavyweight Championship.[4] He had also begun working in Japan, where he became very popular due to his sport wrestling style.[4] He wrestled in the main event of the very first show held by New Japan Pro-Wrestling (NJPW) on March 6, 1972, defeating Antonio Inoki.[25] In the early 1970s, Gotch had a hand at training the first batch of students at the NJPW Dojo. Gotch had previously trained NJPW founding members Inoki and Seiji Sakaguchi. Three notable students of Gotch's were Killer Khan, Tatsumi Fujinami[14] and Yoshiaki Fujiwara. Fujiwara would become the producer of the Karl Gotch Training Book, which detailed the training methods used by Gotch on him and his dojo-mates.[26] His final match occurred on January 1, 1982, when he pinned Yoshiaki Fujiwara with the German suplex.[27] Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Gotch worked as both the booker and trainer for NJPW.[8] He trained several wrestlers in Japan, including Hideki Suzuki, Hiro Matsuda, Satoru Sayama, Osamu Kido, Barry Darsow, Minoru Suzuki, Tatsumi Fujinami, Akira Maeda, and Yoshiaki Fujiwara.[4][8]

Personal life

editIstaz was married to Ella, and had a daughter, Janine Istaz.[8] They resided in Florida until his death.[8] Janine married Masami "Sammy" Soranaka, a protégé of her father's, pro wrestler and referee.[28][29] Soranaka died in 1992 of a brain tumor aged 48.

Legacy and death

editKarl Gotch became known as a "God" (神様, Kami-sama) in Japan.[8] Gotch's wrestling style, alongside fellow hooker Lou Thesz, had a big impact on Inoki, who adopted and popularized his submission-based style. Some of Istaz's trainees founded the Universal Wrestling Federation in Japan in 1984, which showcased the shoot-style of professional wrestling. The success of UWF and similar promotions influenced Japanese wrestling in subsequent decades, and changed the style of matches in NJPW and All Japan Pro Wrestling.[8]

Gotch also influenced the development of mixed martial arts (MMA) through his students including Antonio Inoki, Satoru Sayama, Minoru Suzuki, Masakatsu Funaki, Akira Maeda, and Nobuhiko Takada. Inoki wrestled in a series of matches called ishu kakutōgi sen, where he faced martial artists representing different styles and a legitimate fight against Muhammad Ali in 1976. Inoki hired legitimate martial artists such as Gotch to train his roster and later promoted MMA. Sayama founded Shooto, a hybrid martial art system and promotion. Shooto held its first amateur events in 1985 and its first professional event in 1989, several years prior to the UFC in 1993. Suzuki and Funaki founded Pancrase, which held its first event a month before UFC 1. Maeda founded RINGS, a shoot-style wrestling promotion that became an MMA promotion. And Takada co-founded PRIDE, one of the most popular MMA promotions in history. These students and promotions shaped MMA by producing and featuring many of the top fighters of their time.[30][31][32][33][34]

Several other professional wrestlers who had been, at some point, taught by Gotch include El Canek, Riki Choshu,[14] Masanobu Fuchi, Bob Backlund, and brothers Joe and Dean Malenko.

Gotch was friends and training partners with judo exponents Masahiko Kimura and Kiyotaka Otsubo, who also had tenures as professional wrestlers.[35] Gotch was vocal in his opposition to the growing Brazilian jiu-jitsu, decrying its practitioners as "old whores waiting for a consumer" due to their usage of the guard position.[35]

The German suplex is named after Gotch.[36] Gotch was inducted into the Wrestling Observer Hall of Fame as part of the inaugural class in 1996.[8] In 2007, he was inducted into the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame.[4] He innovated the cradle piledriver and the kneeling belly-to-belly piledriver.

Istaz died on July 28, 2007, in Tampa, Florida, at the age of 82.[5][6]

His ashes were mostly spread in Lake Keystone, Florida. However, in 2017, ten years after his death, some of his ashes were interned at a grave in Ekoin Temple in Arakawa, Tokyo.

Championships and accomplishments

edit- American Wrestling Alliance (Ohio)

- AWA World Heavyweight Championship (1 time)[5]

- George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame

- Class of 2009[37]

- International Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame

- National Wrestling Alliance

- NWA Eastern Heavyweight Championship (2 times)[39]

- New Japan Pro-Wrestling

- Real World Championship (2 times)[5]

- Greatest 18 Club inductee

- Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum

- Tokyo Sports

- Service Award (2007)[40]

- World Championship Wrestling (Australia)

- World Wide Wrestling Federation

- Worldwide Wrestling Associates

- Wrestling Observer Newsletter

- Other titles

- German Heavyweight Championship (1 time)[41]

- European Championship (1 time)[4]

Footnotes

edit- ^ a b c d "Karel ISTAZ". Olympics.com. Retrieved 2024-01-16.

- ^ a b c d "Olympedia – Karel Istaz". www.olympedia.org. Retrieved 2024-01-14.

- ^ a b c "Karl Gotch". Online World of Wrestling. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Oates, Robert K. "Karl Gotch". Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on May 29, 2009. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Gallipoli, Thomas M. (August 22, 2007). "SPECIALIST: List of Deceased Wrestlers for 2007 with Details (Updated as needed)". Pro Wrestling Torch. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ^ a b Caldwell, James (July 29, 2007). "Etc. News: Wrestling legend Karl Gotch dies at age 82 in Florida". Pro Wrestling Torch. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ^ a b Shields, Brian; Sullivan, Kevin (2009). WWE Encyclopedia. DK. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-7566-4190-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Schramm, Chris; Oliver, Greg (July 29, 2007). ""God of Wrestling" legacy on wrestling may be forever Karl Gotch dead at age 82". Slam! Sports. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on February 19, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Snowden, Jonathan (June 2012). Shooters: The Toughest Men in Professional Wrestling. Toronto, Canada: ECW Press. p. 133. ISBN 9781770410404.

- ^ Schramm, Chris (2007-06-29). "Legacy of 'God of Wrestling' Gotch may be forever". Slam Wrestling. Retrieved 2024-01-14.

- ^ "Karl Gotch Week: Satoru Sayama, Shooto And The Style Of Japanese Catch Wrestling". bloodyelbow.com. 2012-07-24. Retrieved 2024-08-15.

- ^ Snowden, Jonathan (2023-09-21). "Pancrase: Ken Shamrock and Masakatsu Funaki Launch a Wrestling Revolution 30 Years Ago Today". Hybrid Shoot. Retrieved 2024-08-15.

- ^ a b Djeljosevic, Danny (2022-02-20). "10 Things Wrestling Fans Should Know About Karl Gotch". TheSportster. Retrieved 2024-08-15.

- ^ a b c "The Snake Pit: Karl Gotch, Billy Robinson, Catch Wrestling and Puroresu". Monthly Puroresu. Retrieved 2024-08-15.

- ^ Dilbert, Ryan. "Andre the Giant vs. Akira Maeda; History of Pro Wrestling Shoots, Part 2". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 2024-08-15.

- ^ Martinez, Stephen (Sep 4, 2007). "Kitaoka Headlines Pancrase's Karl Gotch Memorial". Sherdog. Retrieved 2024-01-17.

- ^ Grant, T.P. (2012-02-12). "MMA Origins: Catch Wrestling Travels to Japan". Bloody Elbow. Retrieved 2024-01-16.

- ^ Grant, T.P. (2012-07-23). "MMA Origins: Birth of Japanese MMA". Bloody Elbow. Retrieved 2024-01-16.

- ^ Gould, KJ (2012-07-24). "Karl Gotch Week: Satoru Sayama, Shooto And The Style Of Japanese Catch Wrestling". Bloody Elbow. Retrieved 2024-01-16.

- ^ Gould, KJ (2012-07-28). "Karl Gotch Week: Rest In Peace Kamisama, 'God Of Wrestling' 1924 – 2007". Bloody Elbow. Retrieved 2024-01-16.

- ^ Evans, Hilary; Gjerde, Arild; Heijmans, Jeroen; Mallon, Bill; et al. "Karl Gotch Olympic Results". Olympics at Sports-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Hatton, Nathan (Jan 12, 2015). "New Billy Riley book informs on both the man and Wigan's Snake Pit". Slam Wrestling. Retrieved 2024-03-22.

- ^ "Karl Gotch, The Quiet Man, Speaks His Piece" – December, 1968

- ^ Graham Cawthon. "WWF Show Results 1971". Retrieved September 8, 2009.

(December 6, 1971) Karl Gotch & Rene Goulet defeated WWWF Tag Team Champions Luke Graham & Tarzan Tyler to win the titles in a Best 2 out of 3 falls match, 2–0, at 17:20

- ^ Zavisa, Chris (September 15, 2002). "5 Yrs Ago: Zavisa on the 25th Anniversary of New Japan Pro Wrestling". Pro Wrestling Torch. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ^ "Karl Gotch's Training Book by Yoshiaki Fujiwara". Budovideos Inc. Retrieved 2024-08-15.

- ^ "1982". Thehistoryofwwe.com. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- ^ Vale, Bart; Jacobs, Mark (Apr 2002). "The Favorite Fighting Philosophies and Techniques of an American Pioneer". Black Belt. Vol. 40, no. 4. p. 62. ISSN 0277-3066. Retrieved 2024-03-21.

- ^ Meltzer, Dave (2013-11-16). "Many pitfalls nearly finished UFC long ago". MMA Fighting. Retrieved 2024-03-21.

- ^ Martinez, Stephen (Sep 4, 2007). "Kitaoka Headlines Pancrase's Karl Gotch Memorial". Sherdog. Retrieved 2024-01-17.

- ^ Grant, T.P. (2012-02-12). "MMA Origins: Catch Wrestling Travels to Japan". Bloody Elbow. Retrieved 2024-01-16.

- ^ Grant, T.P. (2012-07-23). "MMA Origins: Birth of Japanese MMA". Bloody Elbow. Retrieved 2024-01-16.

- ^ Gould, KJ (2012-07-24). "Karl Gotch Week: Satoru Sayama, Shooto And The Style Of Japanese Catch Wrestling". Bloody Elbow. Retrieved 2024-01-16.

- ^ Gould, KJ (2012-07-28). "Karl Gotch Week: Rest In Peace Kamisama, 'God Of Wrestling' 1924 – 2007". Bloody Elbow. Retrieved 2024-01-16.

- ^ a b Yamaguchi, Noboru (1997). 紙のプロレス・ラジカル3号 カール・ゴッチ神様降臨!!. Kamipro.

- ^ "Five very European maneuvers for Antonio Cesaro". WWE. p. 3. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ^ Johnson, Mike (June 30, 2009). "Ricky Steamboat, Nick Bockinkel Among 2009 Class Honored By Wrestling Museum & Institute". PWInsider. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Mike (March 13, 2022). "Steve Austin & More: International Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame Class of 2022 Announced". PWInsider.com. Archived from the original on February 2, 2023. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ "NWA Eastern Heavyweight Championship". Cagematch. Retrieved October 7, 2023.

- ^ 東京スポーツ プロレス大賞. Tokyo Sports (in Japanese). Retrieved 2014-01-20.

- ^ "German Heavyweight Championship Title History". Wrestling-titles. Retrieved 2018-01-06.

References

edit- Catch: The Hold Not Taken (DVD). 2005.

External links

edit- Karel Istaz at Olympics.com

- Karl Gotch's profile at Cagematch.net , Wrestlingdata.com , Internet Wrestling Database