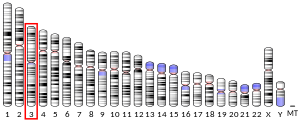

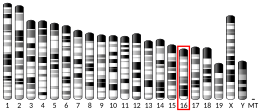

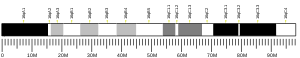

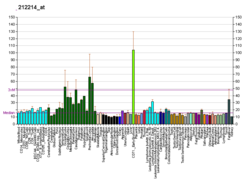

Dynamin-like 120 kDa protein, mitochondrial is a protein that in humans is encoded by the OPA1 gene.[5][6] This protein regulates mitochondrial fusion and cristae structure in the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) and contributes to ATP synthesis and apoptosis,[7][8][9] and small, round mitochondria.[10] Mutations in this gene have been implicated in dominant optic atrophy (DOA), leading to loss in vision, hearing, muscle contraction, and related dysfunctions.[6][7][11]

Structure

editEight transcript variants encoding different isoforms, resulting from alternative splicing of exon 4 and two novel exons named 4b and 5b, have been reported for this gene.[6] They fall under two types of isoforms: long isoforms (L-OPA1), which attach to the IMM, and short isoforms (S-OPA1), which localize to the intermembrane space (IMS) near the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM).[12] S-OPA1 is formed by proteolysis of L-OPA1 at the cleavage sites S1 and S2, removing the transmembrane domain.[9]

The OPA1 transcript may be alternatively spliced to incorporate a poison exon between exons 5 and 6 or between exons 5b and 6.[13]

Function

editThis gene product is a nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein with similarity to dynamin-related GTPases. It is a component of the mitochondrial network.[6] The OPA1 protein localizes to the inner mitochondrial membrane, where it regulates mitochondrial fusion and cristae structure.[7] OPA1 mediates mitochondrial fusion in cooperation with mitofusins 1 and 2 and participates in cristae remodeling by the oligomerization of two L-OPA1 and one S-OPA1, which then interact with other protein complexes to alter cristae structure.[8][14] Its cristae regulating function also contributes to its role in oxidative phosphorylation and apoptosis, as it is required to maintain mitochondrial activity during low-energy substrate availability.[7][8][9] Moreover, stabilization of mitochondrial cristae by OPA1 protects against mitochondrial dysfunction, cytochrome c release, and reactive oxygen species production, thus preventing cell death.[15] Mitochondrial SLC25A transporters can detect these low levels and stimulate OPA1 oligomerization, leading to tightening of the cristae, enhanced assembly of ATP synthase, and increased ATP production.[8] Stress from an apoptotic response can interfere with OPA1 oligomerization and prevent mitochondrial fusion.[9]

Clinical significance

editMutations in this gene have been associated with optic atrophy type 1, which is a dominantly inherited optic neuropathy resulting in progressive loss of visual acuity, leading in many cases to legal blindness.[6] Dominant optic atrophy (DOA) in particular has been traced to mutations in the GTPase domain of OPA1, leading to sensorineural hearing loss, ataxia, sensorimotor neuropathy, progressive external ophthalmoplegia, and mitochondrial myopathy.[7][11] As the mutations can lead to degeneration of auditory nerve fibres, cochlear implants provide a therapeutic means to improve hearing thresholds and speech perception in patients with OPA1-derived hearing loss.[7]

Mitochondrial fusion involving OPA1 and MFN2 may be associated with Parkinson's disease.[11]

Stoke Therapeutics is evaluating the splice-switching antisense oligonucleotide STK-002 as a potential treatment for DOA. STK-002 reduces poison exon inclusion in the OPA1 transcript, leading to increased OPA1 protein levels.[13]

Interactions

editOPA1 has been shown to interact with:

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000198836 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000038084 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Votruba M, Moore AT, Bhattacharya SS (Jan 1998). "Demonstration of a founder effect and fine mapping of dominant optic atrophy locus on 3q28-qter by linkage disequilibrium method: a study of 38 British Isles pedigrees". Human Genetics. 102 (1): 79–86. doi:10.1007/s004390050657. PMID 9490303. S2CID 26060748.

- ^ a b c d e "Entrez Gene: OPA1 optic atrophy 1 (autosomal dominant)".

- ^ a b c d e f Santarelli R, Rossi R, Scimemi P, Cama E, Valentino ML, La Morgia C, Caporali L, Liguori R, Magnavita V, Monteleone A, Biscaro A, Arslan E, Carelli V (Mar 2015). "OPA1-related auditory neuropathy: site of lesion and outcome of cochlear implantation". Brain. 138 (Pt 3): 563–76. doi:10.1093/brain/awu378. PMC 4339771. PMID 25564500.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Patten DA, Wong J, Khacho M, Soubannier V, Mailloux RJ, Pilon-Larose K, MacLaurin JG, Park DS, McBride HM, Trinkle-Mulcahy L, Harper ME, Germain M, Slack RS (Nov 2014). "OPA1-dependent cristae modulation is essential for cellular adaptation to metabolic demand". The EMBO Journal. 33 (22): 2676–91. doi:10.15252/embj.201488349. PMC 4282575. PMID 25298396.

- ^ a b c d Anand R, Wai T, Baker MJ, Kladt N, Schauss AC, Rugarli E, Langer T (Mar 2014). "The i-AAA protease YME1L and OMA1 cleave OPA1 to balance mitochondrial fusion and fission". The Journal of Cell Biology. 204 (6): 919–29. doi:10.1083/jcb.201308006. PMC 3998800. PMID 24616225.

- ^ Wiemerslage L, Lee D (2016). "Quantification of mitochondrial morphology in neurites of dopaminergic neurons using multiple parameters". J Neurosci Methods. 262: 56–65. doi:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2016.01.008. PMC 4775301. PMID 26777473.

- ^ a b c Carelli V, Musumeci O, Caporali L, Zanna C, La Morgia C, Del Dotto V, Porcelli AM, Rugolo M, Valentino ML, Iommarini L, Maresca A, Barboni P, Carbonelli M, Trombetta C, Valente EM, Patergnani S, Giorgi C, Pinton P, Rizzo G, Tonon C, Lodi R, Avoni P, Liguori R, Baruzzi A, Toscano A, Zeviani M (Mar 2015). "Syndromic parkinsonism and dementia associated with OPA1 missense mutations". Annals of Neurology. 78 (1): 21–38. doi:10.1002/ana.24410. PMC 5008165. PMID 25820230.

- ^ Fülöp L, Rajki A, Katona D, Szanda G, Spät A (Dec 2013). "Extramitochondrial OPA1 and adrenocortical function" (PDF). Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 381 (1–2): 70–9. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2013.07.021. PMID 23906536. S2CID 5657510.

- ^ a b Venkatesh, Aditya; McKenty, Taylor; Ali, Syed; Sonntag, Donna; Ravipaty, Shobha; Cui, Yanyan; Slate, Deirdre; Lin, Qian; Christiansen, Anne; Jacobson, Sarah; Kach, Jacob; Lim, Kian Huat; Srinivasan, Vaishnavi; Zinshteyn, Boris; Aznarez, Isabel (2024-10-01). "Antisense Oligonucleotide STK-002 Increases OPA1 in Retina and Improves Mitochondrial Function in Autosomal Dominant Optic Atrophy Cells". Nucleic Acid Therapeutics. 34 (5): 221–233. doi:10.1089/nat.2024.0022. ISSN 2159-3337.

- ^ Fülöp L, Szanda G, Enyedi B, Várnai P, Spät A (2011). "The effect of OPA1 on mitochondrial Ca²⁺ signaling". PLOS ONE. 6 (9): e25199. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025199. PMC 3182975. PMID 21980395.

- ^ Varanita T, Soriano ME, Romanello V, Zaglia T, Quintana-Cabrera R, Semenzato M, Menabò R, Costa V, Civiletto G, Pesce P, Viscomi C, Zeviani M, Di Lisa F, Mongillo M, Sandri M, Scorrano L (Jun 2015). "The OPA1-dependent mitochondrial cristae remodeling pathway controls atrophic, apoptotic, and ischemic tissue damage". Cell Metabolism. 21 (6): 834–44. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2015.05.007. PMC 4457892. PMID 26039448.

Further reading

edit- Olichon A, Guillou E, Delettre C, Landes T, Arnauné-Pelloquin L, Emorine LJ, Mils V, Daloyau M, Hamel C, Amati-Bonneau P, Bonneau D, Reynier P, Lenaers G, Belenguer P (2006). "Mitochondrial dynamics and disease, OPA1". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1763 (5–6): 500–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.04.003. PMID 16737747.

- Pawlikowska P, Orzechowski A (2007). "[Role of transmembrane GTPases in mitochondrial morphology and activity]". Postepy Biochemii. 53 (1): 53–9. PMID 17718388.

- Nagase T, Ishikawa K, Miyajima N, Tanaka A, Kotani H, Nomura N, Ohara O (Feb 1998). "Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. IX. The complete sequences of 100 new cDNA clones from brain which can code for large proteins in vitro". DNA Research. 5 (1): 31–9. doi:10.1093/dnares/5.1.31. PMID 9628581.

- Johnston RL, Seller MJ, Behnam JT, Burdon MA, Spalton DJ (Jan 1999). "Dominant optic atrophy. Refining the clinical diagnostic criteria in light of genetic linkage studies". Ophthalmology. 106 (1): 123–8. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90013-1. PMID 9917792.

- Delettre C, Lenaers G, Griffoin JM, Gigarel N, Lorenzo C, Belenguer P, Pelloquin L, Grosgeorge J, Turc-Carel C, Perret E, Astarie-Dequeker C, Lasquellec L, Arnaud B, Ducommun B, Kaplan J, Hamel CP (Oct 2000). "Nuclear gene OPA1, encoding a mitochondrial dynamin-related protein, is mutated in dominant optic atrophy". Nature Genetics. 26 (2): 207–10. doi:10.1038/79936. PMID 11017079. S2CID 24514847.

- Alexander C, Votruba M, Pesch UE, Thiselton DL, Mayer S, Moore A, Rodriguez M, Kellner U, Leo-Kottler B, Auburger G, Bhattacharya SS, Wissinger B (Oct 2000). "OPA1, encoding a dynamin-related GTPase, is mutated in autosomal dominant optic atrophy linked to chromosome 3q28". Nature Genetics. 26 (2): 211–5. doi:10.1038/79944. PMID 11017080. S2CID 8314863.

- Toomes C, Marchbank NJ, Mackey DA, Craig JE, Newbury-Ecob RA, Bennett CP, Vize CJ, Desai SP, Black GC, Patel N, Teimory M, Markham AF, Inglehearn CF, Churchill AJ (Jun 2001). "Spectrum, frequency and penetrance of OPA1 mutations in dominant optic atrophy". Human Molecular Genetics. 10 (13): 1369–78. doi:10.1093/hmg/10.13.1369. PMID 11440989.

- Thiselton DL, Alexander C, Morris A, Brooks S, Rosenberg T, Eiberg H, Kjer B, Kjer P, Bhattacharya SS, Votruba M (Nov 2001). "A frameshift mutation in exon 28 of the OPA1 gene explains the high prevalence of dominant optic atrophy in the Danish population: evidence for a founder effect". Human Genetics. 109 (5): 498–502. doi:10.1007/s004390100600. PMID 11735024. S2CID 23854938.

- Delettre C, Griffoin JM, Kaplan J, Dollfus H, Lorenz B, Faivre L, Lenaers G, Belenguer P, Hamel CP (Dec 2001). "Mutation spectrum and splicing variants in the OPA1 gene". Human Genetics. 109 (6): 584–91. doi:10.1007/s00439-001-0633-y. PMID 11810270. S2CID 19099209.

- Aung T, Ocaka L, Ebenezer ND, Morris AG, Krawczak M, Thiselton DL, Alexander C, Votruba M, Brice G, Child AH, Francis PJ, Hitchings RA, Lehmann OJ, Bhattacharya SS (Jan 2002). "A major marker for normal tension glaucoma: association with polymorphisms in the OPA1 gene". Human Genetics. 110 (1): 52–6. doi:10.1007/s00439-001-0645-7. PMID 11810296. S2CID 20733038.

- Misaka T, Miyashita T, Kubo Y (May 2002). "Primary structure of a dynamin-related mouse mitochondrial GTPase and its distribution in brain, subcellular localization, and effect on mitochondrial morphology". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (18): 15834–42. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109260200. PMID 11847212.

- Thiselton DL, Alexander C, Taanman JW, Brooks S, Rosenberg T, Eiberg H, Andreasson S, Van Regemorter N, Munier FL, Moore AT, Bhattacharya SS, Votruba M (Jun 2002). "A comprehensive survey of mutations in the OPA1 gene in patients with autosomal dominant optic atrophy". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 43 (6): 1715–24. PMID 12036970.

- Aung T, Ocaka L, Ebenezer ND, Morris AG, Brice G, Child AH, Hitchings RA, Lehmann OJ, Bhattacharya SS (May 2002). "Investigating the association between OPA1 polymorphisms and glaucoma: comparison between normal tension and high tension primary open angle glaucoma". Human Genetics. 110 (5): 513–4. doi:10.1007/s00439-002-0711-9. PMID 12073024. S2CID 13588421.

- Olichon A, Emorine LJ, Descoins E, Pelloquin L, Brichese L, Gas N, Guillou E, Delettre C, Valette A, Hamel CP, Ducommun B, Lenaers G, Belenguer P (Jul 2002). "The human dynamin-related protein OPA1 is anchored to the mitochondrial inner membrane facing the inter-membrane space". FEBS Letters. 523 (1–3): 171–6. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02985-X. PMID 12123827. S2CID 45592235.

- Marchbank NJ, Craig JE, Leek JP, Toohey M, Churchill AJ, Markham AF, Mackey DA, Toomes C, Inglehearn CF (Aug 2002). "Deletion of the OPA1 gene in a dominant optic atrophy family: evidence that haploinsufficiency is the cause of disease". Journal of Medical Genetics. 39 (8): 47e–47. doi:10.1136/jmg.39.8.e47. PMC 1735190. PMID 12161614.

- Satoh M, Hamamoto T, Seo N, Kagawa Y, Endo H (Jan 2003). "Differential sublocalization of the dynamin-related protein OPA1 isoforms in mitochondria". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 300 (2): 482–93. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02874-7. PMID 12504110.

- Olichon A, Baricault L, Gas N, Guillou E, Valette A, Belenguer P, Lenaers G (Mar 2003). "Loss of OPA1 perturbates the mitochondrial inner membrane structure and integrity, leading to cytochrome c release and apoptosis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (10): 7743–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.C200677200. PMID 12509422.

- Shimizu S, Mori N, Kishi M, Sugata H, Tsuda A, Kubota N (Feb 2003). "A novel mutation in the OPA1 gene in a Japanese patient with optic atrophy". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 135 (2): 256–7. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(02)01929-3. PMID 12566046.

- Alavi, MV; Fuhrmann, N (2013). "Dominant optic atrophy, OPA1, and mitochondrial quality control: understanding mitochondrial network dynamics". Molecular Neurodegeneration. 8 (32): 32. doi:10.1186/1750-1326-8-32. PMC 3856479. PMID 24067127.