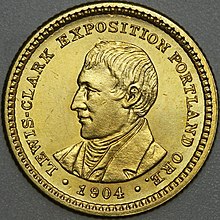

The Lewis and Clark Exposition Gold dollar is a commemorative coin that was struck in 1904 and 1905 as part of the United States government's participation in the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition, held in the latter year in Portland, Oregon. Designed by United States Bureau of the Mint Chief Engraver Charles E. Barber, the coin did not sell well and less than a tenth of the authorized mintage of 250,000 was issued.

United States | |

| Value | 1 US dollar |

|---|---|

| Mass | 1.672 g |

| Diameter | 15 mm |

| Edge | Reeded |

| Composition | |

| Gold | 0.04837 troy oz |

| Years of minting | 1904–1905 |

| Mintage | 1904: 25,000 pieces plus 28 for the Assay Commission, less 15,003 melted 1905: 35,000 plus 41 for the Assay Commission, less 25,000 melted.[2] |

| Mint marks | None. All pieces struck at Philadelphia Mint without mint mark. |

| Obverse | |

| |

| Design | Meriwether Lewis |

| Designer | Charles E. Barber |

| Design date | 1904 |

| Reverse | |

| |

| Design | William Clark |

| Designer | Charles E. Barber |

| Design date | 1904 |

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, the first European-American overland exploring party to reach the Pacific Coast, was led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, following the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Between 1804 and 1806, its members journeyed from St. Louis to the Oregon coast and back, providing information and dispelling myths about the large area acquired by the United States in the Purchase. The Portland fair commemorated the centennial of that trip.

The coins were, for the most part, sold to the public by numismatic promoter Farran Zerbe, who had also vended the Louisiana Purchase Exposition dollar. As he was unable to sell much of the issue, surplus coins were melted by the Mint. The coins have continued to increase in value, and today are worth between hundreds and thousands of dollars, depending on condition. The Lewis and Clark Exposition dollar is the only American coin to be "two-headed", with a portrait of one of the expedition leaders on each side.

Background

editThe Louisiana Purchase in 1803 more than doubled the area of the American nation. Seeking to gain knowledge of the new possession, President Thomas Jefferson obtained an appropriation from Congress for an exploratory expedition, and appointed his private secretary, Meriwether Lewis, to lead it. A captain in the United States Army, Lewis selected William Clark, a former Army lieutenant and younger brother of American Revolutionary War hero George Rogers Clark, as co-leader of the expedition. Lewis and William Clark had served together, and chose about thirty men, dubbed the Corps of Discovery, to accompany them. Many of these were frontiersmen from Kentucky who were in the Army, as well as boatmen and others with necessary skills. The expedition set forth from the St. Louis area on May 14, 1804.[3]

Journeying up the Missouri River, Lewis and Clark met Sacagawea, a woman of the Lemhi Shoshone tribe. Sacagawea had been captured by another tribe and sold as a slave to Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian trapper, who made her one of his wives. Both Charbonneau and Sacagawea served as interpreters for the expedition and the presence of the Native American woman (and her infant son, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau) helped convince hostile tribes that the Lewis and Clark Expedition was not a war party. A great service Sacagawea rendered the expedition was to aid in the purchase of horses, needed so the group could cross the mountains after they had to abandon the Missouri approaching the Continental Divide. One reason for her success was that the Indian chief whose aid they sought proved to be Sacagawea's brother.[4][5]

The expedition spent the winter of 1804–1805 encamped near the site of Bismarck, North Dakota. They left there on April 7, 1805, and came within view of the Pacific Ocean, near Astoria, Oregon, on November 7. After overwintering and exploring the area, they departed eastward on March 23, 1806, and arrived in St. Louis six months to the day later. Only one of the expedition members died en route, most likely of appendicitis. While they did not find the mammoths or salt mountains reputed to be in the American West, "these were a small loss compared to the things that were gained".[4] In addition to knowledge of the territories purchased by the US, these included the establishment of relations with Native Americans and increased public interest in the West once their diaries were published. Further, the exploration of the Oregon Country later aided American claims to that area.[6] In gratitude for their service to the nation, Congress gave Lewis and Clark land grants and they were appointed to government offices in the West.[7]

Inception

editBeginning in 1895, Oregonians proposed honoring the centennial of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with a fair to be held in Portland, a city located along the party's route. In 1900, a committee of Portland businessmen began to plan for the event, an issue of stock was successful in late 1901, and construction began in 1903. A long drive to gain federal government support succeeded when President Theodore Roosevelt signed an appropriations bill on April 13, 1904. This bill allocated $500,000 to exposition authorities,[8] and also authorized a gold dollar to commemorate the fair, with the design and inscriptions left to the discretion of the Secretary of the Treasury. The organizing committee was the only entity allowed to purchase these from the government, and could do so at face value, up to a mintage limit of 250,000.[9]

Numismatist Farran Zerbe had advocated for the passage of the authorization. Zerbe was not only a coin collector and dealer, but he promoted the hobby through his traveling exhibition, "Money of the World". Zerbe, president of the American Numismatic Association from 1908 to 1910, was involved in the sale of commemorative coins for over 20 years, beginning in 1892.[10][11] The Portland exposition's authorities placed him in charge of the sale of the gold dollar.[5]

Details of the preparation of the commemorative dollar are lost; the Mint destroyed many records in the 1960s.[12] Mint Chief Engraver Charles E. Barber was responsible for the designs.[1]

Design

editNumismatic historians Don Taxay and Q. David Bowers both suggest that Barber most likely based his designs on portraits of Lewis and of Clark by American painter Charles Willson Peale found in Philadelphia's Independence Hall.[7][12] Taxay deemed Barber's efforts, "commonplace".[12] The piece is the only American coin to be "two-headed", bearing a single portrait on each side.[13]

Art historian Cornelius Vermeule, in his volume on American coinage, pointed out that some people liked the Lewis and Clark Exposition dollar as it depicted historic figures who affected the course of American history, rather than a bust intended to be Liberty, and that Barber's coin presaged the 1909 Lincoln cent and the 1932 Washington quarter. Nevertheless, Vermeule deprecated the piece, as well as the earlier American gold commemorative, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition dollar. "The lack of spark in these coins, as in so many designs by Barber or Assistant Engraver (later Chief Engraver) Morgan, stems from the fact that the faces, hair and drapery are flat and the lettering is small, crowded, and even."[14] According to Vermeule, when the two engravers collaborated on a design, such as the 1916 McKinley Birthplace Memorial dollar, "the results were almost oppressive".[14]

Production

editThe Philadelphia Mint produced 25,000 Lewis and Clark Exposition dollars in September 1904, plus 28 more, reserved for inspection and testing at the 1905 meeting of the United States Assay Commission. These bore the date 1904.[15] Zerbe ordered 10,000 more in March 1905, dated 1905. The Mint struck 35,000 plus assay pieces in March and June in case Zerbe wanted to buy more, doing so in advance as the Philadelphia Mint shut down in the summer, but as he did not order more, the additional 25,000 were melted.[16]

The Lewis and Clark Exposition dollar was the first commemorative gold coin to be struck and dated in multiple years.[15] A total of 60,069 pieces were struck, from both years, of which 40,003 were melted.[17] According to numismatists Jim Hunt and Jim Wells in their 2004 article on the coin, "the poor reception afforded the coin at the time of issue virtually guaranteed their rarity for future generation".[18]

Aftermath and collecting

editThe Lewis and Clark Centennial and American Pacific Exposition and Oriental Fair opened in Portland on June 1, 1905. It was not designated as an international exposition, and did not draw much publicity even within the United States. Nevertheless, two and a half million people visited the fair between Opening Day and the close on October 14. Sixteen foreign nations accepted invitations from organizers to mount exhibits at the exposition. There was the usual broad array of concessions and midway attractions to entertain visitors.[7] Among Americans who displayed exhibits at the fair were prominent cartoonist and animal fancier Homer Davenport[19] and long-lived pioneer Ezra Meeker. The exposition was one of the few of its kind to make a profit, and likely contributed to a major increase in Portland's population and economy between 1905 and 1912.[8]

Funds from the sale of the coin were designated for the completion of a statue to Sacagawea in a Portland park.[16] There was little mention of the dollar in the numismatic press. Q. David Bowers speculates that Dr. George F. Heath, editor of The Numismatist, who opposed such commemoratives, declined to run any press releases Zerbe might have sent.[17] Nevertheless, an article appeared in the August 1905 issue, promoting the exhibit and dollar. As it quotes Zerbe and praises his efforts, it was likely written by him.[20] Zerbe concentrated on bulk sales to dealers, as well as casual ones at the fair at a price of $2; he enlisted Portland coin dealer D.M. Averill & Company to make retail sales by mail. There were also some banks and other businesses that sold coins directly to the public. Averill ran advertisements in the numismatic press, and in early 1905, raised prices on the 1904 pieces, claiming that they were near exhaustion. This was a lie: in fact, the 1904-dated coins sold so badly that some 15,000 were melted at the San Francisco Mint.[17] Zerbe had Averill sell the 1905 issue at a discounted price of ten dollars for six pieces.[15] As he had for the Louisiana Purchase dollar, Zerbe made the coins available mounted in spoons or in jewelry. Little else is known regarding the distribution of the gold dollars.[17]

The coins were highly unpopular in the collecting community, which had seen the Louisiana Purchase coin decrease in value since its issuance.[17] Nevertheless, the value of the Lewis and Clark issue did not drop below issue price, but steadily increased. Despite a slightly higher number of coins recorded as extant, the 1905 issue is rarer and more valuable than the 1904; Bowers speculates that Zerbe may have held some pieces only to cash them in, or surrender them in 1933 when President Franklin Roosevelt called in most gold coins.[21] The 1905 for many years traded for less than the 1904, but by 1960 had matched the earlier version's price and in the 1980s surpassed it.[22] The 2014 edition of A Guide Book of United States Coins (the Red Book) lists the 1904 at between $900 and $10,000, depending on condition, and the 1905 at between $1,200 and $15,000.[1] One 1904, in near pristine MS-68 condition, sold in 2006 at auction for $57,500.[13]

Despite the relative failure of the coin issue, the statue of Sacagawea was duly erected in a Portland park, financed by coin sales.[1] In 2000, Sacagawea joined Lewis and Clark in appearing on a gold-colored dollar coin, with the issuance of a circulating coin depicting her and her son.[23]

References and bibliography

editCitations

edit- ^ a b c d Yeoman, p. 286.

- ^ Swiatek, p. 77.

- ^ Slabaugh, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b Slabaugh, p. 26.

- ^ a b Flynn, p. 206.

- ^ Flynn, p. 207.

- ^ a b c Bowers, p. 610.

- ^ a b "Guide to the Lewis and Clark Centennial and American Pacific Exposition and Oriental Fair Records, 1894–1933". Northwest Digital Archive. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ^ Flynn, p. 348.

- ^ Hunt & Wells, pp. 41–42.

- ^ American Numismatic Association.

- ^ a b c Taxay, p. 22.

- ^ a b Flynn, p. 208.

- ^ a b Vermeule, p. 105.

- ^ a b c Swiatek, p. 78.

- ^ a b Swiatek & Breen, p. 134.

- ^ a b c d e Bowers, p. 611.

- ^ Hunt & Wells, p. 42.

- ^ Huot & Powers, pp. 123, 132, 159.

- ^ ANA, pp. 239–241.

- ^ Bowers, p. 612.

- ^ Bowers, pp. 612–614.

- ^ Yeoman, p. 234.

Bibliography

editBooks

edit- Bowers, Q. David (1992). Commemorative Coins of the United States: A Complete Encyclopedia. Wolfeboro, NH: Bowers and Merena Galleries, Inc.

- Flynn, Kevin (2008). The Authoritative Reference on Commemorative Coins 1892–1954. Roswell, GA: Kyle Vick. OCLC 711779330.

- Huot, Leland & Powers, Alfred (1973). Homer Davenport of Silverton: Life of a great cartoonist. Bingen, WA: West Shore Press. ISBN 978-1-111-08852-1.

- Slabaugh, Arlie R. (1975). United States Commemorative Coinage (second ed.). Racine, WI: Whitman Publishing (then a division of Western Publishing Company, Inc.). ISBN 978-0-307-09377-6.

- Swiatek, Anthony (2012). Encyclopedia of the Commemorative Coins of the United States. Chicago: KWS Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9817736-7-4.

- Swiatek, Anthony & Breen, Walter (1981). The Encyclopedia of United States Silver & Gold Commemorative Coins, 1892 to 1954. New York: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-04765-4.

- Taxay, Don (1967). An Illustrated History of U.S. Commemorative Coinage. New York: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-01536-3.

- Vermeule, Cornelius (1971). Numismatic Art in America. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-62840-3.

- Yeoman, R.S. (2013). A Guide Book of United States Coins 2014 (67th ed.). Atlanta, GA: Whitman Publishing LLC. ISBN 978-0-7948-4180-5.

Other sources

edit- "ANA Presidents". American Numismatic Association. Archived from the original on July 2, 2013. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- Hunt, Jim; Wells, Jim (March 2004). "Numismatics of the Lewis and Clark Exposition". The Numismatist. Colorado Springs, CO: American Numismatic Association: 40–44.

- Zerbe, Farran (unsigned) (August 1905). "Where one dollar is worth two". The Numismatist. Colorado Springs, CO: American Numismatic Association: 239–241.