You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (March 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Liu Shaoqi (pronounced [ljǒʊ ʂâʊtɕʰǐ]; 24 November 1898 – 12 November 1969) was a Chinese revolutionary and politician. He was the chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress from 1954 to 1959, first-ranking vice chairman of the Chinese Communist Party from 1956 to 1966, and the chairman of the People's Republic of China, the head of state from 1959 to 1968. He was considered to be a possible successor to Mao Zedong, but was purged during the Cultural Revolution.

Liu Shaoqi | |

|---|---|

刘少奇 | |

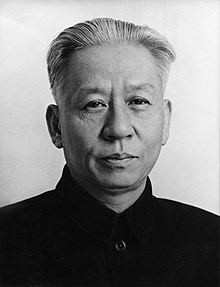

Official portrait, 1950s | |

| 2nd Chairman of the People's Republic of China | |

| In office 27 April 1959 – 31 October 1968 | |

| Premier | Zhou Enlai |

| Vice President | Dong Biwu and Soong Ching-ling |

| Leader | Mao Zedong (Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party) |

| Preceded by | Mao Zedong |

| Succeeded by | Dong Biwu and Soong Ching-ling (acting) |

| 1st Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress | |

| In office 27 September 1954 – 27 April 1959 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Zhu De |

| Vice Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party | |

| In office 28 September 1956 – 1 August 1966 | |

| Chairman | Mao Zedong |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Lin Biao |

| Delegate to the National People's Congress | |

| In office 15 September 1954 – 21 October 1968 | |

| Constituency | Beijing At-large |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 24 November 1898 Ningxiang, Hunan, Qing dynasty |

| Died | 12 November 1969 (aged 70) Kaifeng, Henan, People’s Republic of China |

| Political party | Chinese Communist Party (1921–1968) |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 9 (including Liu Yunbin and Liu Yuan) |

| Liu Shaoqi | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 刘少奇 | ||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 劉少奇 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

In his early years, Liu participated in labor movements in strikes, including the May Thirtieth Movement. After the Chinese Civil War began in 1927, he was assigned by the CCP to work in Shanghai and Northeast China, and travelled to the Jiangxi Soviet in 1932. He participated in the Long March, and was appointed as the Party Secretary in North China in 1936 to lead anti-Japanese resistance efforts in the area. During the Second Sino-Japanese War, Liu led the CCP's Central Plains Bureau. After the New Fourth Army incident in 1941, Liu became a political commissar of the New Fourth Army. After Liu returned to Yan'an in 1943, he became a secretary of the CCP Secretariat and a vice chairman of the Central Military Commission.

After the proclamation of the People's Republic of China in 1949, Liu became a vice chairman of the Central People's Government. After the establishment of the National People's Congress in 1954, Liu was elected as the chairman of its Standing Committee. In 1959, he succeeded Mao Zedong as the chairman of the People's Republic of China. During his chairmanship, he implemented policies of economic reconstruction in China, especially after the Seven Thousand Cadres Conference in 1962. Liu was publicly named as Mao's chosen successor in 1961. However, he was criticized and then purged by Mao soon after the beginning of the Cultural Revolution in 1966, eventually being placed under house arrest in 1967. He was forced out of public life and was labelled the "commander of China's bourgeoisie headquarters", China's foremost "capitalist-roader", and a traitor to the revolution. He died in prison in 1969 due to complications from diabetes. Liu was widely condemned in the years following his death until he was posthumously rehabilitated by Deng Xiaoping's government in 1980, as part of the Boluan Fanzheng period. Deng's government granted Liu a national memorial service.

Youth

editLiu was born into a moderately rich peasant family in Huaminglou,[1] Ningxiang, Hunan province;[2] his ancestral hometown is located at Jishui County, Jiangxi. He received a modern education,[3]: 142 attending Ningxiang Zhusheng Middle School and was recommended to attend a class in Shanghai to prepare for studying in Russia. In 1920, he and Ren Bishi joined a Socialist Youth Corps; the next year, Liu was recruited to study at the Comintern's University of the Toilers of the East in Moscow.[1]

He joined the newly formed Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1921. The next year he returned to China and, as secretary of the All-China Labor Syndicate, led several railway workers' strikes in the Yangzi Valley and at Anyuan on the Jiangxi-Hunan border.[1]

Early political activities

editIn 1925, Liu became a member of the Guangzhou-based All-China Federation of Labor Executive Committee. During the next two years he led numerous political campaigns and strikes in Hubei and Shanghai. He worked with Li Lisan in Shanghai in 1925, organizing Communist activity following the May Thirtieth Movement. After his work in Shanghai, Liu traveled to Wuhan. He was briefly arrested in Changsha and then returned to Guangzhou to help organize the 16-month-long Canton–Hong Kong strike.[4]

He was elected to the Party's Central Committee in 1927 and was appointed to the head of its Labor Department.[5] Liu returned to work at the Party headquarters in Shanghai in 1929 and was named Secretary of the Manchurian Party Committee in Fengtian.[6] In 1930 and 1931 he attended the Third and Fourth Plenums of the Sixth Central Committee, and was elected to the Central Executive Committee (i.e., Politburo) of the Chinese Soviet Republic in 1931 or 1932. Later in 1932, he left Shanghai and traveled to the Jiangxi Soviet.[7]

Liu became the Party Secretary of Fujian Province in 1932. He accompanied the Long March in 1934 at least as far as the crucial Zunyi Conference, but was then sent to the so-called "White Areas" (areas controlled by the Kuomintang) to reorganize underground activities in northern China, centered around Beijing and Tianjin. He became Party Secretary in North China in 1936, leading the anti-Japanese movements in that area with the assistance of Peng Zhen, An Ziwen, Bo Yibo, Ke Qingshi, Liu Lantao, and Yao Yilin. In February 1937 he established, with the rest of the North China Bureau, in Beijing.[8]: 104 In the same year, he challenged Zhang Wentian on the Party's historical problems, criticizing the leftist errors after 1927, thus breaching the consensus reached at the Zunyi Conference that the Party line had been essentially correct.[8]: 103 Liu ran the Central Plains Bureau in 1939; and, in 1941, the Central China Bureau.

In 1937, Liu traveled to the Communist base at Yan'an; in 1941, he became a political commissar of the New Fourth Army.[9] He was elected as one of five CCP Secretaries at the Seventh Party Congress in 1945. In a report following the 7th Congress, Liu articulated four "mass points" to be instilled in every party member: "everything for the masses; full responsibility to the masses; faith in the self-emancipation of the masses; and learning from the masses".[10]

After that Congress, he became the supreme leader of all Communist forces in Manchuria and northern China,[9] a role frequently overlooked by historians.

People's Republic of China

editLiu became the Vice Chairman of the Central People's Government in 1949. In 1954 China adopted a new constitution at the first National People's Congress (NPC); at the Congress's first session, he was elected chairman of the Congress's Standing Committee, a position he held until the second NPC in 1959. From 1956 until his downfall in 1966, he ranked as the First Vice Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party.[9]

Liu's work focused on party organizational and theoretical affairs.[11] He drafted party regulations and oversaw the organizational development of the party consistent with Marxist-Leninist principles.[12]: 18–19 He was an orthodox Soviet-style Communist and favored state planning and the development of heavy industry. He elaborated upon his political and economic beliefs in his writings. His best known works include How to be a Good Communist (1939), On the Party (1945), and Internationalism and Nationalism (1952).

State Chairman

editLiu spoke very strongly in favor of the Great Leap Forward at the Eighth CCP National Congress in May 1958. However, he later expressed concerns about the adverse effects of the campaign, particularly the widespread famine it caused. During the Lushan Conference in 1959, Liu emphasized the need for corrective measures and supported more moderate economic policies.[13] At this Congress Liu stood together with Deng Xiaoping and Peng Zhen in support of Mao's policies against those who were more critical, such as Chen Yun and Zhou Enlai.

As a result, Liu gained influence within the party. In April 1959, he succeeded Mao as Chairman of the People's Republic of China (Chinese President). However, Liu began to voice concern about the outcomes of the Great Leap in August 1959 Lushan Conference.[13] To correct the mistakes of the Great Leap Forward, Liu and Deng Xiaoping led economic reforms that bolstered their prestige among the party apparatus and the national populace. The economic policies of Deng and Liu were notable for being more moderate than Mao's radical ideas. For example, in the period when the economic turmoil of the Great Leap Forward prompted the Party to delay the Third Five Year Plan, Liu led a group of high officials who worked to revive the economy through an increased role for markets, greater material incentives for workers, a lower rate of investment, a more moderate pace for developmental goals, and increased funding for consumer industries.[14]: 40 During preliminary work on the Third Five Year Plan, Liu stated:[14]: 51

In the past, the infrastructure battlefront was too long. There were too many projects. Demands were too high and rushed. Designs were done badly, and projects were hurriedly begun ... We only paid attention to increasing output and ignored quality. We set targets too highly. We must always remember these painful learning experiences.

Conflict with Mao

editLiu was publicly acknowledged as Mao's chosen successor in 1961; however, by 1962 his opposition to Mao's policies had led Mao to mistrust him. Liu's advocacy for pragmatic economic reforms and his criticism of the Great Leap Forward's failures highlighted the ideological rift between him and Mao.[15] After Mao succeeded in restoring his prestige during the 1960s,[16] Liu's eventual downfall became "inevitable". Liu's position as the second-most powerful leader of the CCP contributed to Mao's rivalry with him at least as much as Liu's political beliefs or factional allegiances in the 1960s,[15] especially during and after the Seven Thousand Cadres Conference, indicating that Liu's later persecution was the result of a power struggle that went beyond the goals and well-being of either China or the Party.

Liu was among the senior officials who in 1964 were initially reluctant to support Mao's proposed Third Front campaign to develop basic industry and national defense industry in China's interior to address the risk of invasion by the United States or the Soviet Union.[14]: 41 In an effort to stall, Liu proposed additional surveys and planning.[14]: 40 Academic Covell F. Meyskens writes that Liu and the high-ranking colleagues who agreed with him did not want to engage in another rapid industrialization campaign so soon after the failure of the Great Leap Forward and that instead they sought to continue the gradual approach of developing areas and increasing consumption.[14]: 41 When fears of American invasion increased after the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, Liu and his colleagues changed their views and began fully supporting the Third Front construction.[14]: 7

By 1966, few senior leaders in China questioned the need for a widespread reform to combat the growing problems of corruption and bureaucratization within the Party and the government. With the goal of reforming the government to be more efficient and true to the Communist ideal, Liu himself chaired the enlarged Politburo meeting that officially began the Cultural Revolution. However, Liu and his political allies quickly lost control of the Cultural Revolution soon after it was called, when Mao used the movement to progressively monopolize political power and to destroy his perceived enemies.[17]

Whatever its other causes, the Cultural Revolution, declared in 1966, was overtly pro-Maoist, and gave Mao the power and influence to purge the Party of his political enemies at the highest levels of government. Along with closing China's schools and universities, and Mao's exhortations to young Chinese to randomly destroy old buildings, temples, and art, and to attack their teachers, school administrators, party leaders, and parents,[18] the Cultural Revolution also increased Mao's prestige so much that entire villages adopted the practice of offering prayers to Mao before every meal.[19]

In both national politics and Chinese popular culture, Mao established himself as a demigod accountable to no one, purging any that he suspected of opposing him[20] and directing the masses and Red Guards "to destroy virtually all state and party institutions".[17] After the Cultural Revolution was announced, most of the most senior members of the CCP who had voiced any hesitation in following Mao's direction, including Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, were removed from their posts almost immediately and, with their families, subjected to mass criticism and humiliation.[18] Liu and Deng, along with many others, were denounced as "capitalist roaders".[21] Liu was labeled as the "commander of China's bourgeoisie headquarters", China's foremost "capitalist-roader", "the biggest capitalist roader in the Party", and a traitor to the revolution;[22] he was displaced as Vice Chairman of the CCP by Lin Biao in July 1966.

By 1967, Liu and his wife Wang Guangmei were placed under house arrest in Beijing.[23] Liu's major economic positions were attacked, including his "three freedoms and one guarantee" (which promoted private land plots, free markets, independent accounting for small enterprises, and household output quotas) and "four freedoms" (which permitted individuals in the countryside to lease land, lend money, hire wage laborers, and engage in trade).[24] Liu was removed from all his positions and expelled from the Party in October 1968. After his arrest, Liu disappeared from public view.

Vilification, death and rehabilitation

editAt the Ninth Party Congress, Liu was denounced as a traitor and an enemy agent. Zhou Enlai read the Party verdict that Liu was "a criminal traitor, enemy agent and scab in the service of the imperialists, modern revisionists and the Kuomintang reactionaries". Liu's conditions did not improve after he was denounced in the Congress, and he died soon afterward.[25][26]

In a memoir written by Liu's principal physician, he disputed the alleged medical maltreatment of Liu during his last days. According to Dr. Gu Qihua, there was a dedicated medical team in charge of treating Liu's illness; between July 1968 and October 1969, Liu had seven total occurrences of pneumonia due to his deteriorating immune system, and there had been a total of 40 group consultations by top medical professionals regarding the treatment of this disease. Liu was closely monitored on a daily basis by a medical team, and they made the best effort given the adverse circumstances. He died in prison from complications due to diabetes at 6:45 a.m. on 12 November 1969 under a pseudonym in Kaifeng, and was cremated the next day.[27][28][23]

In February 1980, two years after Deng Xiaoping came to power, the Fifth Plenum of the 11th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party issued the "Resolution on the Rehabilitation of Comrade Liu Shaoqi". The resolution fully rehabilitated Liu, declaring his ouster to be unjust and removing the labels of "renegade, traitor and scab" that had been attached to him at the time of his death.[21] It also declared him to be "a great Marxist and proletarian revolutionary" and recognized him as one of the principal leaders of the Party. Lin Biao was blamed for "concocting false evidence" against Liu, and for working with the Gang of Four to subject him to "political frame-up and physical persecution". In 1980, Liu was posthumously rehabilitated by the CCP under Deng Xiaoping. This rehabilitation included a formal apology from the government, acknowledging that Liu had been wrongly persecuted and that his contributions to the Chinese Revolution and the early development of the People's Republic of China were significant and positive.[29] Following the conclusion of the rehabilitation ceremony, Liu's ashes were scattered off the coast of the city of Qingdao in accordance to wishes he made prior to his death.[30]

On 23 November 2018, the CCP's general secretary Xi Jinping delivered a speech in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing to commemorate the 120th anniversary of the birth of Liu Shaoqi.[31]

Liu Shaoqi's legacy remains controversial in China. While his role in the Chinese Revolution and early economic reforms is acknowledged, his persecution during the Cultural Revolution and the subsequent suffering highlight the complexities of his political career. Liu's pragmatic approach to economic policy is now seen as a precursor to the reforms that transformed China in the late 20th century.[32]

Personal life

editLiu married five times, including to He Baozhen (何宝珍) and Wang Guangmei (王光美).[33] His third wife, Xie Fei (谢飞), came from Wenchang, Hainan and was one of the few women on the 1934 Long March.[34] His wife at the time of his death in 1969, Wang Guangmei, was thrown into prison by Mao Zedong during the Cultural Revolution; she was subjected to harsh conditions in solitary confinement for more than a decade.[35]

His son Liu Yunbin (Chinese: 刘允斌; pinyin: Liú Yǔnbīn) was a prominent physicist who was also singled out for abuse during the Cultural Revolution. He committed suicide in 1967 by lying on the tracks before an oncoming train. Liu Yunbin was posthumously rehabilitated and his reputation restored in 1978.

Works

edit- Liu Shaoqi (1984). Selected Works of Liu Shaoqi. Vol. I (1st ed.). Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 0-8351-1180-6. Archived from the original on 6 December 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- — (1991). Selected Works of Liu Shaoqi. Vol. II (1st ed.). Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 0-8351-2452-5. Archived from the original on 6 December 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

See also

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ a b c Dittmer, Lowell, Liu Shao-ch’i and the Chinese Cultural Revolution: The Politics of Mass Criticism, University of California Press (Berkeley), 1974, p. 27

- ^ Snow, Edgar, Red Star Over China, Random House (New York), 1938. Citation is from the Grove Press 1973 edition, pp. 482–484

- ^ Hammond, Ken (2023). China's Revolution and the Quest for a Socialist Future. New York, NY: 1804 Books. ISBN 9781736850084.

- ^ Dittmer, p. 14

- ^ Chen, Jerome. Mao and the Chinese Revolution, (London), 1965, p. 148

- ^ Dittmer, p. 15

- ^ Snow, pp. 482–484

- ^ a b Gao Hua, How the Red Sun Rose: The Origins and Development of the Yan'an Rectification Movement, 1930–1945, Chinese University of Hong Kong Press. 2018

- ^ a b c Dittmer 1974, p. 17 citing Tetsuya Kataoka, Resistance and Revolution in China: The Communists and the Second United Front, 1974 pre-publication.

- ^ MacFarquhar, Roderick (1973). "Problems of Liberalization and the Succession at the Eighth Party Congress". The China Quarterly (56): 617–646. doi:10.1017/S0305741000019524. ISSN 0305-7410. JSTOR 652160.

- ^ Dittmer 1974, p. 206

- ^ Tsang, Steve; Cheung, Olivia (2024). The Political Thought of Xi Jinping. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197689363.

- ^ a b Dikötter, Frank. Mao's Great Famine: The History of China's Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958-62. Walker & Company, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Meyskens, Covell F. (2020). Mao's Third Front: The Militarization of Cold War China. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-78478-8. OCLC 1145096137.

- ^ a b Teiwes, Frederick C., and Warren Sun. The Tragedy of Lin Biao: Riding the Tiger during the Cultural Revolution, 1966-1971. University of Hawaii Press, 1996.

- ^ Spence, Jonathan D. The Search for Modern China, New York: W.W. Norton and Company. 1999. ISBN 0-393-97351-4 p. 566.

- ^ a b Qiu Jin, The Culture of Power: the Lin Biao Incident in the Cultural Revolution, Stanford University Press: Stanford, California. 1999, p. 45

- ^ a b Spence, Jonathan D. The Search for Modern China, New York: W.W. Norton and Company. 1999. ISBN 0-393-97351-4 p. 575.

- ^ Spence, Jonathan D. The Search for Modern China, New York: W.W. Norton and Company. 1999. ISBN 0-393-97351-4 p. 584

- ^ Barnouin, Barbara and Yu Changgen. Zhou Enlai: A Political Life. Hong Kong: Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2006. ISBN 962-996-280-2 p. 4

- ^ a b Dittmer, Lowell (1981). "Death and Transfiguration: Liu Shaoqi's Rehabilitation and Contemporary Chinese Politics". The Journal of Asian Studies. 40 (3): 455–479. doi:10.2307/2054551. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 2054551.

- ^ "Liu Shaoqi (1898-1969)". Chinese University of Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 4 June 2018.

- ^ a b Mathews, Jay (4 March 1980). "5 Children of Liu Shaoqi Detail Years in Disfavor". Washington Post. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ Coderre, Laurence (2021). Newborn socialist things : materiality in Maoist China. Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-1478014300.

- ^ Chung, Jang. White Swans: Three Daughters of China. Touchstone: New York. 2003. p. 391. ISBN 0-7432-4698-5.

- ^ Glover, Jonathan (1999). Humanity : A Moral History of the Twentieth Century. London: J. Cape. p. 289. ISBN 0-300-08700-4.

- ^ 回忆抢救刘少奇, 炎黄春秋 [Liu Shaoqi's Emergency Treatment] (in Chinese (China)). Sina.com History. 12 November 2013.

- ^ Alexander V. Pantsov . Mao: The Real Story . Simon & Schuster 2013. p. 519. ISBN 1451654480.

- ^ Vogel, Ezra F. Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China. Harvard University Press, 2011.

- ^ "Rehabilitation of Liu Shaoqi (Feb. 1980)". China Internet Information Center. 22 June 2011. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

- ^ "Xi's speech commemorating 120th anniversary of Liu Shaoqi's birth published". People's Daily. 4 December 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ Lo Porto-Lefébure, Alessia (6 March 2009). "NAUGHTON (Barry) – The Chinese Economy. Transitions and Growth . – Cambridge (Mass.), The MIT Press, 2007. 528 p." Revue française de science politique. 59 (1): IV. doi:10.3917/rfsp.591.0134d. ISSN 0035-2950.

- ^ 前国家主席刘少奇夫人王光美访谈录 (in Chinese (China)). Sina.com. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ 长征时与刘少奇结伉俪,琼籍女红军传奇人生 (in Chinese (China)). Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ Lieberthal, Kenneth. Governing China: From Revolution to Reform. W.W. Norton: New York, 1995.[ISBN missing]

Sources

edit- "Fifth Plenary Session of 11th C.C.P. Central Committee", Beijing Review, No. 10 (10 March 1980), pp. 3–10, which describes the official rehabilitation measures.