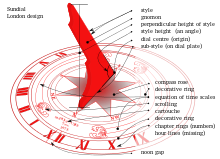

A London dial in the broadest sense can mean any sundial that is set for 51°30′ N, but more specifically refers to a engraved brass horizontal sundial with a distinctive design. London dials were originally engraved by scientific instrument makers. The trade was heavily protected by the system of craft guilds.

A horizontal dial

editA gnomon or style is set to point at the celestial north pole, the shadow of the Sun is thrown onto the dial plate and will appear at the same position each day of the year, and this position can be calculated using trigonometry, or drawn using geometric construction. In the world of sundials some of the technical terms use an old form of language, so the angle to which the style is set is called the style height. The style height is identical to the geographical latitude, and in London this was 51 degrees 30 minutes or 51.50 degrees, which roughly corresponds with Westminster Bridge.

The gnomon has thickness, and thus two shadow throwing edges (the styles) one for the morning and one for the afternoon, there is a gap left on the dialplate the width of the gnomon.

A sundial displays the local apparent time, and watches that use mean time or average time will always be at a slight variance. This difference of time can be calculated and displayed on the dial – again using old language it is known as the equation of time.[a] A London dials show hour lines, some show half-hour markers, the quarter hours and some divisions representing half-quarters (7 and a half minutes). The equation of time is shown as a three rings, showing the words WATCH SLOWER, WATCH FASTER, the months and dates and the minutes of time of variance.

Geometrical construction

editThere are many methods to do this: the one published by Leybourn in 1652 is still popular.[1] Though the one by Dom Francois Bedos de Celles in 1790 is more widely known.[2]

Calculations

edit- Style height

-

- Hour lines (mark from 4am to 8pm)

-

- where is the angle from noon line, and

- is the geographical latitude.

Definitions

edit- Centre of delineation

- the point where the styles and all the hour lines meet. On a dials with a thick gnomon, there will be two centres of delineation, separated by a noon gap.

- Gnomon

- the vertical triangular component. The gnomon is precisely angled for the latitude, in London that is nominally 51° 30' N. The London gnomon has thickness so the style that casts the shadow for the morning hours is the western edge of the gnomon while the eastern edge of the gnomon is the style that cast the shadow for the afternoon hours.

- Chapter ring

- this is the ring of written numbers. On the chapter ring may be half-hour indicators and quarter-hour indicators.

Timeline

edit- 1500s

- Written evidence of dials (Reign Henry VII)

- 1542

- Nicholas Oursian- this is the earliest example in a museum. It is dated with inwardly facing roman numerals. The origin or centre of delineation is the centre of the dialplale. It has simple decoration, a large Tudor Rose beneath the style.[3]

- 1578

- A dial (maker unknown) for Sir Philip Sidney (1554-1586). Decoration included a ropework border, and scrolls at the end of the chapter ring.

- 1580s

- Simple punched dials- for use by the less wealthy, though the gnomon started to have a complex shape.

- 1590

- Isaack Symmes, a 'gouldsmith'(sic) was producing dials. The centre of delineation moved to the southern edge of the dial, the division now included hours, half-hours and quarter hours. The lettering could be gushing, reflecting the developments in calligraphy and silverwork. Some Symmes dials included a volvelle.

- Jacobean

- 1588-1653

- Elias Allen, the mathematical instrument maker. These were accurate with austere decoration.

- 1665

- Henry Sutton (1649-1665), a renowned engraver of scientific instruments, was a victim of the plague.

- 1660

- Regime change The restored aristocracy restored their houses and decorated their gardens. Decorative sundials were in demand.

- 1680s

- Henry Wynne

- 1680

- Flamsteed's Equation of Time Tables were available. Diallists experimented on how the information should be included on the dial. Thomas Tompion used calendar tables, Wynne preferred linear strip tables. The tables were then drawn as concentric arcs around the compass rose. The early arcs were labelled as Equation of Natural Days- later they included the text Watch Fast. This chapter ring was separated from the compass rose by a decorative ring of oak-leaves.

- 1700

- Wynne retired and his workshop was passed to Thomas Wright- Thomas Tuttell and Richard Glynne

- 1700s

- John Rowley made the hour numbers face outwards, this was adopted by all London diallists and by 1750 in all of the provinces.

- 1700s

- The change of orientation of the Equation of Natural Days came in two stages, firstly a simple reversal that led to the months running backward, then secondly the months were reversed to run left to right, ie counterclockwise.

- 1750

- Mathematical instrument makers moved to a factory system, with workshops of journeymen just doing a small part of the dial. Thomas Heath had a large workshop.[4] Dials were no longer signed by one man. The name was that of the manufactory or even the retailer. Decorations came from a pattern book, these would be scrolls on the Equation of Time ring, coats of arm and cartouches for signatures.

- 1800

- Simplification of design. The oakleaf decoration was replaced by a zigzag design. Troughton & Simms was one of the last of the mathematical instrument makers who made dials.

- 1850s

- The need for accurate dials decreased as time was transmitted electrically. Francis Barker and Son[5] issued a catalogue of decorative designs.

- 1880s

- Machine (pantograph) engraving started. The Watch Faster/Slower ring was removed being replaced by a simple table then after 1920 a graph.

- 1900s

- Emergence of fake dials, with mottoes and Father Time figures suns and other symbols. These had a false date and spurious makers names: these were sold by companies such as Pearson Page Ltd or Peerless Brass to meet customer demand.[6]

Geometrical markup technique

editA horizontal dial, takes the equiangular hour lines of a equatorial dial and projects them onto a plane oblique to the style, the markup simulates this transformation.

The Dom Francois Bedos de Celles method (1760) [7] otherwise known as the Waugh method (1973) [8]

- Take a large sheet of paper.

- Starting at the bottom, draw a line across, and a vertical one up the centre. Where they cross is important call it O.

- Choose the size of the dial, and draw a line across. Where it crosses the centre line is important call it F

- You know your latitude. Draw a line upwards from O at this angle, this is a construction line.

- Using a square, (drop a line) draw a line from F through the construction line so they cross at right angles. Call that point E, it is important. To be precise it is the line FE that is important as it is length .

- Using compasses, or dividers the length FE is copied upwards in the centre line from F. The new point is called G and yes it is important- the construction lines and FE can now be erased.

- From G a series of lines, 15° apart are drawn, long enough so they cross the line through F. These mark the hour points 9, 10, 11, 12, 1, 2, 3 if you take just 3 and represent the points .

- The centre of the dial is at the bottom, point O. The line drawn from each of these hour point to O will be the hour line on the finished dial.[9]

- If the paper is large enough, the method above works from 7 until 12, and 12 until 5 and the values before and after 6 are calculated through symmetry. However, there is another way of marking up 7 and 8, and 4 and 5. Call the point where 3 crosses the line R, and a drop a line at right-angles to the base line. Call that point W. Use a construction line to join W and F. Waugh calls the crossing points with the hours lines K, L, M.

- Using compasses or dividers, add two more points to this line N and P, so that the distances MN = ML, and MP = MK. The missing hour lines are drawn from O through N and through P. The construction lines are erased.[9]

-

Setting out a dial for 52°N. The three initial lines.

-

Marking the latitude, laying out length , and copying to G on the vertical.

-

From G casting on the horizontal.

-

The actual hour lines 9, 10, 11, 12, 1, 2, 3.

-

Construction lines removed.

-

Constructing the 7, 8, 4, 5 lines

-

Marking the 7, 8, 4, 5 lines

-

The completed dial plate for 52°N. Bedos de Celles (1790)

Caveat: These diagrams have not been tested for accuracy. The further north the wider the dial becomes.

Notable examples

edit- Beamish museum

- There are two London dials, the first is in 'town' by the Solicitors Office. It is dated 1649. The second is in the garden of Pockerley Manor, this is a dial produced by Spencer, Browning & Co, more noted for their production of sextants and navigational instruments.

- St Michael's Mount, Cornwall

- There is a dial engraved by Troughton and Simms.

References

edit- ^ Equation is used in the sense of 'changes needed to make equal'. Style height, and style distance both refer to angles. This is seventeenth century usage.

- ^ Leybourn, Art of Dialing (1652, 1669)

- ^ Waugh 1973, p. 39.

- ^ "Horizontal Dial signed by Nicolas Oursian 1542". Epact. Museum of the History of Science, Oxford. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ^ "Tycho Wing Astrologer and Instrument maker 1726 - 1776". Twickenham Museum. Twickenham Museum. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ "Francis Barker 1819-1875". Trade Mark London. Trade Mark London. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ Davis 2014, p. 51.

- ^ Bédos de Celles 1760, p. 58.

- ^ Waugh 1973, p. 38.

- ^ a b Waugh 1973, pp. 38–39.

Bibliography

edit- Bédos de Celles, Francois (1760). "4-3". La Gnomonique pratique ou l'Art de tracer les cadrans solaires avec la plus grande précision (in French) (3 ed.). Paris. p. 459. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- Davis, John (June 2014). "Engraved decoration English-Horizontal dials" (PDF). Bulletin. 26 (ii). British Sundial Society: 48–52. ISSN 0958-4315. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- Waugh, Albert E. (1973). Sundials : their theory and construction. New York: Dover. p. 38–39. ISBN 0486229475.