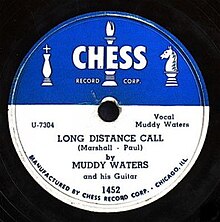

"Long Distance Call" is a song by American blues musician Muddy Waters. It was first released as a single in 1951 by Chess Records (#1452),[1] with "Too Young To Know" on the B-side. The single reached #8 on the US R&B chart.[2] It was later released on the greatest hits album The Best of Muddy Waters (1958), and is hailed as a classic modern blues song; Waters's singing is cited as an excellent example of blue notes.

Background and content

edit"Long Distance Call" originates in the song "Long Distance Moan", recorded in September 1929 by Blind Lemon Jefferson (Paramount #12852).[1] In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Muddy Waters was recording the type of music that helped the blues survive as a commercially viable type of music. "Long Distance Call" was recorded on 23 January 1951, with Little Walter on harmonica and Ernest "Big" Crawford on bass, in a session that also produced "Too Young To Know", "Honey Bee", and "Howlin' Wolf".[3][4][5]

The lyrics feature a male first-person speaker addressing his female lover, asking her to say something kind to him. When a call comes, long-distance, it is only to tell him that "another mule [is] kickin' in your stall".[6] John Collis calls the song a "slow, meditative and soulful strut" that has Waters (a Mississippi native then working in Chicago) "exploit migration as a commercial theme".[3]

Reception and analysis

editEnglish trumpeter and broadcaster Humphrey Lyttelton reviewed the song (and "Hello Little Girl") in 1955 in New Musical Express, saying Waters is "a genuine contemporary blues singer".[7] In a 1969 interview, Muddy Waters himself said it was his favorite song out of all the songs he had recorded.[8] Luther "Georgia Boy" Johnson, a member of Waters's band in the 1960s, co-opted the song as his own, "complete with Muddy's gospel preaching at the song's climax".[9]

David Dicaire, in Blues Singers: Biographies of 50 Legendary Artists of the Early 20th Century, calls the song "a definitive modern blues classic".[4] David Hatch and Stephen Millward, in an analysis of blue notes, single out the song because, in their opinion, it displays Muddy Waters's mastery of blues singing, particularly his "sliding effortlessly between the major and the 'blue' tones, with just the right mixture of hope and bitterness in his voice".[10]

References

edit- ^ a b Herzhaft, Gérard (1992). Encyclopedia of the Blues (2 ed.). U of Arkansas P. p. 273. ISBN 9781610751391.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (1988). Top R&B Singles 1942–1988. Record Research. p. 435. ISBN 0-89820-068-7.

- ^ a b Collis, John (1998). The Story of Chess Records. Bloomsbury. pp. 43–44. ISBN 9781582340050.

- ^ a b Dicaire, David (1999). Blues Singers: Biographies of 50 Legendary Artists of the Early 20th Century. McFarland. p. 81. ISBN 9780786406067.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (1989). Muddy Waters: Chess Box (Box set booklet). Muddy Waters. Chess/MCA Records. OCLC 154264537. CHD3-80002.

- ^ This last phrase is cited as an example of third-person boasting. See Melnick, Mimi Clar (1973). "'I Can Peep Through Muddy Water and Spy Dry Land': Boasts in the Blues". In Alan Dundes (ed.). Mother Wit from Laughing Barrel. UP of Mississippi. pp. 267–76. ISBN 9781617034329.

- ^ Schwartz, Roberta Freund (2013). How Britain Got the Blues: The Transmission and Reception of American Blues Style in the United Kingdom. Ashgate. pp. 56 n.26. ISBN 9781409493761.

- ^ O'Neal, Jim; van Singel, Amy (2013). The Voice of the Blues: Classic Interviews from Living Blues Magazine. Routledge. p. 201. ISBN 9781136707414.

- ^ Komara, Edward (2005). Encyclopedia of the Blues. Psychology Press. p. 534. ISBN 9780415926997.

- ^ Hatch, David; Millward, Stephen (1987). From Blues to Rock: An Analytical History of Pop Music. Manchester UP. pp. 60–61. ISBN 9780719014895.