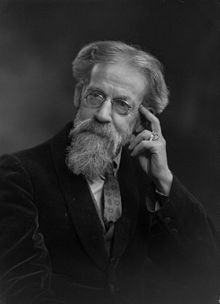

Sir Patrick Geddes FRSE (2 October 1854 – 17 April 1932) was a Scottish biologist,[2] sociologist, Comtean positivist, geographer, philanthropist and pioneering town planner. He is known for his innovative thinking in the fields of urban planning and sociology. His works contain one of the earliest examples of the 'think globally, act locally' concept in social science.[3]

Sir Patrick Geddes | |

|---|---|

Geddes in 1931 | |

| Born | 2 October 1854 Ballater, Aberdeenshire, Scotland |

| Died | 17 April 1932 (aged 77) Scots College, Montpellier, France |

| Alma mater | Royal School of Mines |

| Known for | Urban planning and the term conurbation |

| Spouse | Anna Geddes |

| Children | Norah Geddes |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Sociology, urban planning, biology |

| Institutions | Lecturer in Zoology, University of Edinburgh (1880–1888) Professor of Botany, University College, Dundee (1888–1919) Professor of Civics & Sociology, Bombay University, India (1920–1923) |

| Patrons | John Sinclair, 1st Baron Pentland |

| Signature | |

| |

| Notes | |

Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (1880) Co-founder of the University of Bombay[1] Co-founder of the Sociological Society[1] Founder of the Edinburgh Social Union[1] Founder of the Franco-Scottish Society[1] Planned the Hebrew University at Jerusalem[1] Founder of the Collège des Écossais in Montpellier (1924) | |

Following the philosophies of Auguste Comte and Frederic LePlay, he introduced the concept of "region" to architecture and planning and coined the term "conurbation".[4][5][6][7] Later, he elaborated "neotechnics" as the way of remaking a world apart from over-commercialization and money dominance.[8]

An energetic Francophile,[9] Geddes was the founder in 1924 of the Collège des Écossais (Scots College), an international teaching establishment in Montpellier, France, and in the 1920s he bought the Château d'Assas to set up a centre for urban studies.

Biography

editThe son of Janet Stevenson and soldier Alexander Geddes, Patrick Geddes was born in Ballater and the Old Parish Register for baptisms in the parish of Glenmuick Tullich and Glengairn recorded his first name as 'Peter'.[10] He was educated in Aberdeenshire, and at Perth Academy.[11][page needed]

He studied at the Royal College of Mines in London under Thomas Henry Huxley between 1874 and 1877, never finishing any degree and he then spent the year 1877-1878 as a demonstrator in the Department of Physiology in University College London where he met Charles Darwin in Burdon-Sanderson's laboratory.[12] While in London, he became acquainted with Comtean Positivism, as promoted by Richard Congreve, and he converted to the Religion of Humanity. He was elected as a member of the London Positivist Society. Later he raised his children to worship 'Humanity' following the Positivist system of belief.[5][6][7] He lectured in Zoology at Edinburgh University from 1880 to 1888.

From 1888 to 1918, Geddes worked as a Professor of Botany at the University of Dundee.[13]

He married Anna Morton (1857–1917), who was the daughter of a wealthy merchant, in 1886 when he was 32 years old. They had three children: Norah, Alasdair and Arthur. During a visit to India in 1917, Anna fell ill with typhoid fever and died, not knowing that their son Alasdair had been killed in action in France.[14] Their daughter was the landscape designer Norah Geddes, who was active in Geddes's Open Spaces projects; she married the architect and planner Frank Charles Mears.[15]

In 1890, he assisted John Wilson in laying out a teaching garden at Morgan Academy in Dundee.[16]

Between 1894 and 1914, he served as an active member of the ruling Council of the Cockburn Association, a campaigning conservation organisation founded in Edinburgh in 1875.[17]

In 1895, Geddes published an edition of The Evergreen magazine, with articles on nature, biology and poetics. Artists Robert Burns and John Duncan provided illustrations for the magazine.[18]

Geddes wrote with J. Arthur Thomson an early book on The Evolution of Sex (1889).[19] He held the Chair of Botany at University College Dundee from 1888 to 1919, and the Chair of Sociology at the University of Bombay from 1919 to 1924. He inspired Victor Branford to form the Sociological Society in 1903 to promote his sociological views.

While he thought of himself primarily as a sociologist, it was his commitment to close social observation and ability to turn these into practical solutions for city design and improvement that earned him a "revered place amongst the founding fathers of the British town planning movement".[20] He was a major influence on the American urban theorist Lewis Mumford.

He was knighted in 1932, shortly before his death at the Scots College in Montpellier, France on 17 April 1932.[21]

Town planning career

editPatrick Geddes was influenced by social theorists such as Auguste Comte (1798–1857), Herbert Spencer (1820–1903), and French theorist Frederic Le Play (1806–1882) and expanded upon earlier theoretical developments that led to the concept of regional planning.

He was a proponent of the Comte-LePlay view of the interconnectedness of city region as a potentially autonomous unit.[22] He adopted Spencer's theory that the concept of biological evolution could be applied to explain the evolution of society, and drew on Le Play's analysis of the key units of society as constituting "Lieu, Travail, Famille" ("Place, Work, Family"), but changing the last from "family" to "folk".[23] In this theory, the family is viewed as the central "biological unit of human society"[24][25] from which all else develops. According to Geddes, it is from "stable, healthy homes" providing the necessary conditions for mental and moral development that come beautiful and healthy children who are able "to fully participate in life".[26]

Geddes drew on Le Play's circular theory of geographical locations presenting environmental limitations and opportunities that in turn determine the nature of work. His central argument was that physical geography, market economics and anthropology were related, yielding a "single chord of social life [of] all three combined".[25][27] Thus the interdisciplinary subject of sociology was developed into the science of "man’s interaction with a natural environment: the basic technique was the regional survey, and the improvement of town planning the chief practical application of sociology".[25][28]

Geddes' writing demonstrates the influence of these ideas on his theories of the city. He saw the city as a series of common interlocking patterns, "an inseparably interwoven structure", akin to a flower. He criticised the tendency of modern scientific thinking to specialisation. In his "Report to the H.H. the Maharaja of Kapurthala" in 1917 he wrote:

"Each of the various specialists remains too closely concentrated upon his single specialism, too little awake to those of the others. Each sees clearly and seizes firmly upon one petal of the six-lobed flower of life and tears it apart from the whole."[26]

These ideas can also be traced back to Geddes' abiding interest in Eastern philosophy which he believed more readily conceived of "life as a whole": "as a result, civic beauty in India has existed at all levels, from humble homes and simple shrines to palaces magnificent and temples sublime."[26]

Geddes distinguished two forms of human social life: ‘paleotechnic’ and ‘neotechnic.’ He viewed the former as self-destructive but the latter as self-supporting. In the context of cities, paleotechnic cities are those characterized by competition while neotechnic is characterized by interaction. Additionally, this is followed by the paleotechnic city’s desire for expansion as compared to the neotechnic city’s ability to form communities and conurbations. Geddes attributed the destruction of cities via World War I not to the invasion of imperialist powers but the prevalence of paleotechnic forms of life in European society.[29]

Against a backdrop of extraordinary development of new technologies, industrialisation and urbanism, Geddes witnessed the substantial social consequences of crime, illness and poverty that developed as a result of modernisation. From Geddes' perspective, the purpose of his theory and understanding of relationships among the units of society was to find an equilibrium among people and the environment to improve such conditions.

Key ideas

edit"Conservative surgery" versus the gridiron plan

editGeddes championed a mode of planning that sought to consider "primary human needs" in every intervention, engaging in "constructive and conservative surgery"[30] rather than the "heroic, all of a piece schemes"[31] popular in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He continued to use and advocate for this approach throughout his career.

Very early on in his career Geddes demonstrated the practicality of his ideas and approach. In 1886 Geddes and his wife, Anna Geddes, purchased a row of slum tenements in James Court, Edinburgh, making it into a single dwelling. In and around this area Geddes commenced upon a project of "conservative surgery": "weeding out the worst of the houses that surrounded them…widening the narrow closes into courtyards" and thus improving sunlight and airflow.[32] The best of the houses were kept and restored. Geddes believed that this approach was both more economical and more humane.

In this way Geddes consciously worked against the tradition of the "gridiron plan", resurgent in colonial town design in the 19th century:

"The heritage of the gridiron plans goes back at least to the Roman camps. The basis for the grid as an enduring and appealing urban form rests on five main characteristics: order and regulatory, orientation in space and to elements, simplicity and ease of navigation, speed of layout, and adaptability to circumstance".[33]

However, he wished this policy of "sweeping clearances" to be recognised for what he believed it was: "one of the most disastrous and pernicious blunders in the chequered history of sanitation".[34]

Geddes criticised this tradition as much for its "dreary conventionality" as for its failure to address in the long term the very problems it purport to solve. According to Geddes' analysis, this approach was not only "unsparing to the old homes and to the neighbourhood life of the area" but also, in "leaving fewer housing sites and these mostly narrower than before" expelling a large population that would "again as usual, be driven to create worse congestion in other quarters".[33]

The "observational technique"

editDrawing on the scientific method, Geddes encouraged close observation as the way to discover and work with the relationships among place, work and folk. In 1892, to allow the general public an opportunity to observe these relationships, Geddes opened a "sociological laboratory" called the Outlook Tower that documented and visualized the regional landscape. In keeping with scientific process and using new technologies, Geddes developed an Index Museum to categorise his physical observations and maintained Encyclopedia Graphicato, which used a camera obscura to provide an opportunity for the general public to observe their own landscape to witness the relationships among units of society. Geddes would host tours throughout the tower and boast its maps, photographs, and projection via ‘camera obscura’ in order to present the sociological dimensions of cities, urban problems, and town planning. During his tours he would use the camera obscura on the top floor to demonstrate the outlook of an artist then take visitors to the balcony to show the outlook of technical professionals like geologists, geographers, etc. He used specific instruments and tools to better convey the outlook different people had of the region. The Outlook Tower is a physical assertion of Geddes belief in the importance of all areas of knowledge; all arts, all sciences, all, religions, all cultures, etc. The Outlook Tower embodies the integration of local, the regional, and the global aspects of knowledge. Geddes used it as a tool for cultural and regional analysis and provided space for many thinkers to explore the idea of 'regions' which he later introduced to the field of planning.[35] The Outlook Tower is located in Edinburgh's Old Town and still exists today as Camera Obscura & World of Illusions.[36]

The "civic survey"

editGeddes advocated the civic survey as indispensable to urban planning: his motto was "diagnosis before treatment". Such a survey should include, at a minimum, the geology, the geography, the climate, the economic life, and the social institutions of the city and region. His early work surveying the city of Edinburgh became a model for later surveys.

He was particularly critical of that form of planning which relied overmuch on design and effect, neglecting to consider "the surrounding quarter and constructed without reference to local needs or potentialities".[37] Geddes encouraged instead exploration and consideration of the "whole set of existing conditions", studying the "place as it stands, seeking out how it has grown to be what it is, and recognising alike its advantages, its difficulties and its defects":

"This school strives to adapt itself to meet the wants and needs, the ideas and ideals of the place and persons concerned. It seeks to undo as little as possible, while planning to increase the well-being of the people at all levels, from the humblest to the highest."[37]

In this sense he can be viewed as prefiguring the work of seminal urban thinkers such as Jane Jacobs, and region-specific planning movements such as New Urbanism, encouraging the planner to consider the situation, inherent virtue and potential in a given site, rather than "an abstract ideal that could be imposed by authority or force from the outside".[38]

The regional plan

editIn 1909, Geddes assisted in the early planning of the southern aspect of the Zoological Gardens in Edinburgh.[39] This work was formative in his development of a regional planning model called the "Valley Section".This model illustrated the complex interactions among biogeography, geomorphology and human systems and attempted to demonstrate how "natural occupations" such as hunting, mining, or fishing are supported by physical geographies that in turn determine patterns of human settlement.[40] The point of this model was to make clear the complex and interrelated relationships between humans and their environment, and to encourage regional planning models that would be responsive to these conditions.[41]

Civic pageant

editGeddes developed a means for engaging with the populace of a city through a civic pageant. One such was the Masque of Learning, a pageant he organised in the Poole's Synod Hall, Edinburgh in 1912.[42] He also organised a pageant in Indore, India when he arrived in 1917.[43]

Work in India

editGeddes' work in improving the slums of Edinburgh led to an invitation from Lord Pentland (then Governor of Madras) to travel to India to advise on emerging urban planning issues, in particular, how to mediate "between the need for public improvement and respect for existing social standards".[44] For this, Geddes prepared an exhibition on "City and Town Planning". The materials for the first exhibit were sent to India on a ship that was sunk near Madras by the German ship Emden, however new materials were collected and an exhibit prepared for the Senate hall of Madras University by 1915.

Once arriving in India, Geddes toured multiple Indian cities and was overwhelmed by Indian architecture and planning. Geddes was impressed by the historical piety valued in Indian planning displayed by the seamless merger of traditional temples within the urban fabric of Indian cities. Geddes believed that this was indicative of a city's genius loci which is often established by a visually dominant building in a city like a medieval cathedral or an antique temple in the urban fabric. Geddes was outspoken in his town-planning reports about the “insensitivity of British colonial administration towards the historic Indian architecture and urban environment” and denounced their methods of planning which included drastic and destructive changes to the urban fabric.[29]

According to some reports, this was near the time of the meeting of the Indian National Congress and Pentland hoped the exhibit would demonstrate the benefits of British rule.[45] Geddes lectured and worked with Indian surveyors and travelled to Bombay and Bengal where Pentland's political allies Lord Willingdon and Lord Carmichael were Governors. He held a position in Sociology and Civics at Bombay University from 1919 to 1925.[29]

Between 1915 and 1919 Geddes wrote a series of "exhaustive town planning reports" on at least eighteen Indian cities, a selection of which has been collected together in Jacqueline Tyrwhitt’s Patrick Geddes in India (1947).

Through these reports, Geddes was concerned to create a "working system in India", righting the wrongs of the past by making interventions in and plans for the urban fabric that were both considerate of local context and tradition and awake to the need for development. According to Lewis Mumford, writing in introduction to Tyrwhitt’s collected reports:

"Few observers have shown more sympathy…with the religious and social practices of the Hindus than Geddes did; yet no one could have written more scathingly of Mahatma Gandhi's attempt to conserve the past by reverting to the spinning wheel, at a moment when the fundamental poverty of the masses in India called for the most resourceful application of the machine both to agricultural and industrial life."[46]

His principles for town planning in Bombay demonstrate his views on the relationship between social processes and spatial form, and the intimate and causal connections between the social development of the individual and the cultural and physical environment. They included: ("What town planning means under the Bombay Town Planning Act of 1915")[45]

- Preservation of human life and energy, rather than superficial beautification.

- Conformity to an orderly development plan carried out in stages.

- Purchasing land suitable for building.

- Promoting trade and commerce.

- Preserving historic buildings and buildings of religious significance.

- Developing a city worthy of civic pride, not an imitation of European cities.

- Promoting the happiness, health and comfort of all residents, rather than focusing on roads and parks available only to the rich.

- Control over future growth with adequate provision for future requirements.

Geddes' exhortation to pay attention to the social and particular when attempting city renewal or resettlement remains relevant, particularly in light of the plans for slum resettlement and redevelopment ongoing in many Indian cities (see, e.g. Dharavi redevelopment program):

"Town Planning is not mere place-planning, nor even work planning. If it is to be successful it must be folk planning. This means that its task is not to coerce people into new places against their associations, wishes, and interest, as we find bad schemes trying to do. Instead its task is to find the right places for each sort of people; place where they will really flourish. To give people in fact the same care that we give when transplanting flowers, instead of harsh evictions and arbitrary instructions to 'move on', delivered in the manner of an officious policeman."[47]

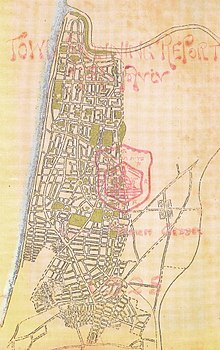

Work in Palestine

editGeddes worked with his son-in-law, the architect Frank Mears, on a number of projects in Palestine. In 1919, he designed a plan for the Hebrew University of Jerusalem at the request of the psychoanalyst, Dr. David Eder, who headed the World Zionist Organization's London Branch.[48][49][50] He also submitted a report on Jerusalem Actual and Possible to the Military Governor of Jerusalem in November 1919.[51][52] In 1925 he submitted a report on town planning in Jaffa and Tel Aviv to the Municipality of Tel Aviv, then led by Meir Dizengoff.[53] The municipality adopted his proposals and Tel Aviv is the only city whose core is entirely laid out according to a plan by Geddes.

Recognition and legacy

editGeddes' ideas had worldwide circulation: his most famous admirer was the American urban theorist Lewis Mumford who claimed that "Geddes was a global thinker in practice, a whole generation or more before the Western democracies fought a global war".[46]

Geddes also influenced several British urban planners (notably Raymond Unwin and Frank Mears), the Indian social scientist Radhakamal Mukerjee and the Catalan architect Cebrià de Montoliu (1873–1923) as well as many other 20th-century thinkers.[54]

Geddes was keenly interested in the science of ecology, an advocate of nature conservation and strongly opposed to environmental pollution. Because of this, some historians have claimed he was a forerunner of modern Green politics.[55]

In August 1982, during the Edinburgh International Festival, Edinburgh College of Art mounted an exhibition entitled On the Side of Life: Patrick Geddes 1854 - 1932, designed by John L. Paterson.[56]

In 2000, a Patrick Geddes Heritage Trail was created on Edinburgh's Royal Mile by the Patrick Geddes Memorial Trust.[57]

Researchers at the Geddes Institute for Urban Research at the University of Dundee continue to develop Geddesian approaches to questions of city and regional planning and questions of social and psychical well-being in the built environment. In late 2015 the University staged an exhibition of Geddes' work in the Lamb Gallery, drawn from the Archives of the Universities of Dundee, Strathclyde, and Edinburgh, to mark the centenary of the publication of Cities in Evolution.[58]

In 2008, the Scottish Historic Building Trust (SHBT) was approached to imagine a future for Riddle's Court in Edinburgh's Lawnmarket, which Geddes had restored for use as a university hall of residence in 1890. Between 2015 and 2017, the Trust undertook a major conservation and regeneration project at the building to create a venue for conferences, meetings and weddings. Riddle's Court now houses the Patrick Geddes Centre for Learning, an educational arm of SHBT.[59]

Buildings

edit- The David Wolffsohn University and National Library, Hebrew University, Jerusalem. Design by Patrick Geddes, Frank Mears and Benjamin Chaikin, inaugurated on 15 April 1930.[60]

Published works

edit- The Evolution of Sex (1889) with J.A. Thomson, W. Scott, London.

- The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal (1895/96), Patrick Geddes and Colleagues, Lawnmarket, Edinburgh.

- City Development, A Report to the Carnegie Dunfermline Trust (1904), Rutgers University Press.[61]

- The Masque of Learning (1912)

- Cities in Evolution (1915) Williams & Norgate, London.

- The life and work of Sir Jagadis C. Bose (1920) Longman, London.

- Biology (1925) with J.A. Thomson, Williams & Norgate, London.

- Life: Outlines of General Biology (1931) with J.A. Thomson, Harper & Brothers, London.

Further reading

edit- Boardman, Philip (1944), Patrick Geddes: Maker of the Future, The University of Carolina Press

- Boardman, Philip (1978), The Worlds of Patrick Geddes: Biologist, Town Planner, Re-educator, Peace-warrior, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, ISBN 0-7100-8548-6

- Defries, Amelia (1927), The Interpreter Geddes: The Man and His Gospel, George Routlege & Sons

- Dolev, Diana (2016), The Planning and Building of the Hebrew University: Facing the Temple Mount, 1919 - 1948, Lexington Books, New York, ISBN 978-0-7391-9161-3

- 'Evaluer la pérennité urbaine : l’example du plan Geddes pour Tel-Aviv', Pérennité urbaine, ou la ville par-delà ses métamorphose, C. Vallat, A. Le Blanc, Pascale Philifert (ed.) Volume I : Traces, Paris, L'Harmattan, 2009, p. 315-325.

- Hubbard, Tom (2013), Patrick Geddes and the Call of the South, in Hubbard, Tom (2022), Invitation to the Voyage: Scotland, Europe and Literature, Rymour, ISBN 9-781739-596002

- Hysler-Rubin, Noah (2011), Patrick Geddes and Town Planning: A Critical View, Routledge, London, ISBN 978-0-415-57867-7

- Kitchen, Paddy (1975), A Most Unsettling Person: An Introduction to the Ideas and Life of Patrick Geddes, Victor Gollancz, London, ISBN 0-575-01957-3

- Macdonald, Murdo (ed.) (1992), "Patrick Geddes: Ecologist, Educator, Visual Thinker", Edinburgh Review, Summer 1992, ISBN 0-7486-6132-8

- Macdonald, Murdo (2020), Patrick Geddes's Intellectual Origins, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-1-4744-5408-7

- Mairet, Philip (1957), Pioneer of Sociology: The Life and Letters of Patrick Geddes, Lund Humphries

- Meller, Helen (1980), "Cities and Evolution: Patrick Geddes as an international prophet of town planning before 1914", in Sutcliffe, Anthony (ed.) The Rise of Modern Urban Planning, 1800 - 1914, Mansell Publishing, pp. 199 - 223, ISBN 0-7201-0902-7

- Meller, Helen (1981), "Patrick Geddes 1854 - 1932", in Cherry, Gordon E. (ed.), Pioneers in British Planning, The Architectural Press Ltd., London, pp. 46 - 71, ISBN 0-85139-563-5

- Meller, Helen (1990), Patrick Geddes: Social Evolutionist and City Planner, Routledge, London, ISBN 9-780415-103930

- Mumford, Lewis (1958), "Patrick Geddes, Victor Branford, and Applied Sociology in England", in An Introduction to the History of Sociology, edited by Barnes, Harry Elmer, 677–95. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- Purves, Graeme (1997), "Scottish Environmentalism: The Contribution of Patrick Geddes", in Eastwood, Colin (ed.), John Muir Trust Journal & News No. 22, pp. 21 - 24.

- Purves, Graeme, "A Vision of Zion", in Roy, Kenneth (ed.), The Scottish Review No. 21, Spring 2000, pp. 83 – 91, ISSN 1356-5737

- Renwick, Chris; Gunn, Richard C. (2008). "Demythologizing the machine: Patrick Geddes, Lewis Mumford, and classical sociological theory". Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. 44 (1): 59–76. doi:10.1002/jhbs.20282. ISSN 0022-5061. PMID 18196543.

- Renwick, Chris (March 2009). "The practice of Spencerian science: Patrick Geddes's Biosocial Program, 1876-1889". Isis. 100 (1): 36–57. doi:10.1086/597574. ISSN 0021-1753. PMID 19554869. S2CID 41671443.

- Scott, John; Bromley, Ray (2013), Envisioning Sociology, State University of New York Press, Albany

- Shaw, Michael (2020), The Fin-de-Siècle Scottish Revival: Romance, Decadence and Celtic Identity, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-1-4744-3395-2

- Tyrwhitt, Jaqueline (ed.) (1947), Patrick Geddes in India, Lund Humphries, London

- Weill-Rochant, Catherine (2006). Le plan de Patrick Geddes pour la " ville blanche " de Tel Aviv : une part d'ombre et de lumière. Volume 1 (PDF) (PhD thesis). Paris: Université Paris 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2010. and Weill-Rochant, Catherine (2006). Le plan de Patrick Geddes pour la " ville blanche " de Tel Aviv : une part d'ombre et de lumière. Volume 2 (PhD thesis). Paris: Université Paris 8. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- Weill-Rochant, Catherine (2008), L'Atlas de Tel-Aviv

- Weill-Rochant, Catherine (2010), Le travail de Patrick Geddes à Tel-Aviv, un plan d'ombres et de lumières, Editions universitaires européennes, (693 pp., plans historiques, photos, figures)

- Welter, Volker M. and Lawson, James (eds.) (2000), The City after Patrick Geddes, Peter Lang, ISBN 9783906764696

- Welter, Volker M. (2002), Biopolis: Patrick Geddes and the City of Life, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, ISBN 9-780262-731645

- Wilson, Matthew (2018), Moralising Space, Routledge, London

- Wright, T.R. (1986), The Religion of Humanity: the Impact of Comtean Positivism on Victorian Britain, Cambridge University Press

See also

edit- Scottish Renaissance

- Geddes Island

- Lady Stair’s House

- Ramsay Garden

- James Cadenhead, Scottish artist who worked with Geddes on his projects in Edinburgh's Old Town.

- List of urban theorists

- Pro-Jerusalem Society (1918-1926) - Geddes was a member of its leading Council

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Macdonald, Murdo (20 May 2009). "Sir Patrick Geddes and the Scottish Generalist Tradition". Royal Society of Edinburgh. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ "Geddes, Patrick". Who's Who. Vol. 59. 1907. p. 666. Geddes wrote many unsigned articles on biology for the Encyclopædia Britannica and also Chambers's Encyclopaedia.

- ^ Geddes, Patrick (1915). Cities in Evolution. London: Williams. p. 397.

- ^ "UCL Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis - CASA News: PATRICK GEDDES AND THE DIGITAL AGE". 8 July 2007. Archived from the original on 8 July 2007. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ a b Mary., Pickering (2009). Auguste Comte: Volume 3.; An Intellectual Biography. Cambridge University Press. p. 571. ISBN 978-0-521-11914-6. OCLC 710898330.

- ^ a b R., Wright, T. (2008). The religion of humanity : the impact of Comtean positivism on Victorian Britain. Cambridge University Press. pp. 260–8. ISBN 978-0-521-07897-9. OCLC 488975315.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Wilson, Matthew (11 May 2018). Moralising Space. New York, NY : Routledge, 2018. | Series: Routledge research in planning and urban design: Routledge. pp. 151–80. doi:10.4324/9781315449128. ISBN 978-1-315-44912-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 287.

- ^ King, Emilie Boyer (5 July 2004). "Anniversary makeover for Geddes garden". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ http://www.ScotlandsPeople.gov.uk Births and Baptisms, 1854 OPR 201/20 123, page 123.

- ^ Waterston, Charles D; Macmillan Shearer, A (July 2006). Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783-2002: Biographical Index (PDF). Vol. I. Edinburgh: The Royal Society of Edinburgh. ISBN 978-0-902198-84-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2006. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ^ M. Batty & S. Marshall (2008) Geddes at UCL: There was something more in town planning than met the eye! CASA Working Paper 138, Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis, University College London [1]

- ^ MacDonald, Murdo (2005). "Celticism and Internationalism in the Circle of Patrick Geddes". Visual Culture in Britain. 6 (2): 69–83 – via EBSCO.

- ^ "Neilson, Kate. "Anna Geddes." Late Bloomers". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- ^ Siân Reynolds (23 November 2019) [2017]. "Geddes, Anna, n. Morton". In Elizabeth Ewan, Rose Pipes (ed.). The New Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 157–58. ISBN 9781474436298.

- ^ "Former Pupil Biographies". The Madras College Archive. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ "Historic Cockburn Association Office-Bearers".

- ^ The Scottish National Gallery, 2016

- ^ Patrick Geddes: Social Evolutionist and City Planner by Helen Meller, (pgs. 81-4), Routledge, 1993,

- ^ Meller, H. (1981). Gordon E. Cherry (ed.). Patrick Geddes 1854-1932. London: The Architectural Press.

- ^ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ Wilson, Matthew (11 May 2018). Moralising Space. New York, NY : Routledge, 2018. | Series: Routledge research in planning and urban design: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315449128. ISBN 978-1-315-44912-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ John., Scott (2014). Envisioning sociology : victor branford, patrick geddes, and the quest for social reconstruction. State Univ Of New York Pr. ISBN 978-1-4384-4730-8. OCLC 861260909.

- ^ Mairet, Philip (1957): Pioneer of Sociology: The Life and Letters of Patrick Geddes, Lund Humphries, London.

- ^ a b c Munshi, Indra (2000): Patrick Geddes: Sociologist, Environmentalist and Town Planner in Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 35, no. 6 (5-11 Feb. 2000), p. 485-491.

- ^ a b c Geddes, Patrick (1947). "Town Planning in Kapurthala. A Report to H.H. the Maharaja of Kapurthala, 1917". In Jacqueline Tyrwhitt (ed.). Patrick Geddes in India. London: Lund Humphries. p. 26.

- ^ Geddes, Patrick. 'Sociology as Civics' in Philip Abrams, The Origins of British Sociology, University of Chicago Press 1968.

- ^ Halliday, R J (1968): "The Sociological Movement, The Sociological Society and the Genesis of Academic Sociology in Britain", The Sociological Review, Vol 16, No 3, NS, November.

- ^ a b c Welter, Volker M. (1999). "Arcades for Lucknow: Patrick Geddes, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Reconstruction of the City". Architectural History. 42: 316–332. doi:10.2307/1568717. ISSN 0066-622X. JSTOR 1568717. S2CID 192322553.

- ^ Mumford, Lewis (1947). in Jaqueline Tyrwhitt (ed.). Patrick Geddes in India. London: Lund Humphries. p. 10.

- ^ Freestone, R (2012). Urban Nation: Australia's Planners. Collingwood: CSIRO Publishing. p. 69.

- ^ Geddes, A (1947). in Jaqueline Tyrwhitt (ed.). Patrick Geddes in India. London: Lund Humphries. p. 15.

- ^ a b Geddes, Patrick (1947). "Report on the Towns in the Madras Presidency, 1915: Tanjore". In Jacqueline Tyrwhitt (ed.). Patrick Geddes in India. London: Lund Humphries. p. 17.

- ^ Geddes, Patrick (1947). "Report on the Towns in the Madras Presidency, 1915: Ballary". In Jacqueline Tyrwhitt (ed.). Patrick Geddes in India. London: Lund Humphries. p. 23.

- ^ MacDonald, Murdo (1994). "The Outlook Tower: Patrick Geddes in Context: Glossing Lewis Mumford in the Light of John Hewitt". The Irish Review (16): 53–73. doi:10.2307/29735756. ISSN 0790-7850. JSTOR 29735756.

- ^ "The Life and Times of Sir Patrick Geddes". Camera Obscura and World of Illusions Edinburgh. Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ a b Geddes, Patrick (1947). "Town Planning in Kapurthala. A Report to H.H. the Maharaja of Kapurthala, 1917". In Jacqueline Tyrwhitt (ed.). Patrick Geddes in India. London: Lund Humphries. p. 24.

- ^ Mumford, Lewis (1947). in Jaqueline Tyrwhitt (ed.). Patrick Geddes in India. London: Lund Humphries. p. 12.

- ^ Edinburgh Zoo. "Our History". Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ Thompson, Catarine (2004). "Geddes, Zoos and the Valley Section". Landscape Review. 10.

- ^ Geddes (1918):Town Planning Towards City Development: A Report to the Durbar of Indore, Holkar State Printing Press, Indore, Vols I and II.

- ^ Pagan, Hugh. "The masque of ancient learning and its many meanings. A pageant of education from primitive to celtic times devised and interpreted by Patrick Geddes. - Hugh Pagan Ltd". www.hughpagan.com. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ Levinson, David; Christensen, Karen (2003). Encyclopedia of Community: From the Village to the Virtual World. SAGE. p. 533. ISBN 9780761925989.

- ^ Geddes, Patrick (1947). "H.V.Lanchester". In Jacqueline Tyrwhitt (ed.). Patrick Geddes in India. London: Lund Humphries. p. 16.

- ^ a b Robert Home (1997) Of Planting and Planning: the making of British colonial cities. E. & F.N. Spon. ISBN 0-203-44961-4

- ^ a b Geddes, Patrick (1947). "Lewis Mumford". In Jacqueline Tyrwhitt (ed.). Patrick Geddes in India. London: Lund Humphries. p. 9.

- ^ Geddes, Patrick (1947). "Report on the Towns in the Madras Presidency, 1915, Madura". In Jacqueline Tyrwhitt (ed.). Patrick Geddes in India. London: Lund Humphries. p. 22.

- ^ Geddes. P. (1919), The Proposed Hebrew University of Jerusalem: A Preliminary Report, December 1919.

- ^ Dolev, Diana (2016) The Planning and Building of the Hebrew University, 1919-1948: Facing the Temple Mount, Lexington Books, pp. 25-44.

- ^ Purves, Graeme (2000), A Vision of Zion, The Scottish Review Number 21, Spring 2000, pp. 83-94)

- ^ Geddes, P. (1919), Jerusalem Actual and Possible, A Report to the Chief Administrator of Palestine and the Military Governor of Jerusalem on Town Planning and City Improvements, November 1919.

- ^ Gideon.An Empire in the Holy Land: Historical Geography of the British Administration in Palestine, 1917-1929, St. Martin's Press, New York & Magnes Press, Jerusalem, p. 216.

- ^ Geddes, P. (1925), Town Planning Report: Jaffa and Tel Aviv, Municipality of Tel Aviv

- ^ For Geddes' influence on these thinkers, see Meller, (pgs. 220,300-3) 1993, and Varieties of Environmentalism: Essays North and South by Guha and Juan Martínez Alier, Earthscan Publications, 1997.

- ^ See Modern Environmentalism: An Introduction by David Pepper, Routledge, 1996, and Environmentalism: A Global History (pgs. 59-62) by Ramachandra Guha, Longman, 1999.

- ^ On the Side of Life: Patrick Geddes 1854 - 1932, programme for the exhibition celebrating the Edinburgh work of Patrick Geddes at the Edinburgh College of Art, 1982

- ^ Leonard, Sofia (2000), Edinburgh Patrick Geddes Memorial Trail, Patrick Geddes Memorial Trust, Edinburgh

- ^ Jarron, Matthew. "The City is a Thinking Machine". University of Dundee Museum Services. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ Hollis, Edward (2018), A Drama in Time: A Guide to 400 years of Riddle's Court, Scottish Historic Buildings Trust, Edinburgh, p. 12, ISBN 9781780275550

- ^ Diana Dolev (2016). The Planning and Building of the Hebrew University, 1919–1948: Facing the Temple Mount. Lexington Books. pp. 71–74. ISBN 9780739191613.

- ^ "City development, a study of parks, gardens, and culture-institutes; a report to the Carnegie Dunfermline trust". 1904.

External links

edit- The online Journal of Civics & Generalism, is an international collaborative project with extensive essays and graphic material inspired by the work of Patrick Geddes in a modern context

- Geddes as a pioneer landscape architect

- The Geddes Institute at Dundee University, Scotland Archived 30 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Works by Patrick Geddes at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Patrick Geddes at the Internet Archive

- Works by Patrick Geddes at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Sir Patrick Geddes Memorial Trust

- Geddes' "The Scots Renascense"

- Records relating to Sir Patrick Geddes at Dundee University Archives[permanent dead link]

- National Library of Scotland Learning Zone, Patrick Geddes: By Living We Learn

- Escuela de Vida "Vivendo discimus", Ceuta (Spain)

- The Patrick Geddes Centre at Riddle's Court