The personal life of Marcus Tullius Cicero provided the underpinnings of one of the most significant politicians of the Roman Republic. Cicero, a Roman statesman, lawyer, political theorist, philosopher, and Roman constitutionalist, played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. A contemporary of Julius Caesar, Cicero is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.[1][2]

Marcus Tullius Cicero | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 3, 106 BC Arpinum, Italy |

| Died | December 7, 43 BC Formia, Italy |

| Occupation | Politician, lawyer, orator and philosopher |

| Nationality | Ancient Roman |

| Subject | politics, law, philosophy, oratory |

| Literary movement | Golden Age Latin |

| Notable works | Politics: Pro Quinctio Philosophy: De Inventione, De Officiis Law: In Verrem |

Cicero is generally perceived to be one of the most versatile minds of ancient Rome. He introduced the Romans to the chief schools of Greek philosophy and created a Latin philosophical vocabulary, distinguishing himself as a linguist, translator, and philosopher. An impressive orator and successful lawyer, Cicero probably thought his political career his most important achievement. Today, he is appreciated primarily for his humanism and philosophical and poltical writings. His voluminous correspondence, much of it addressed to his friend Atticus, has been especially influential, introducing the art of refined letter writing to European culture. Cornelius Nepos, the 1st-century BC biographer of Atticus, remarked that Cicero's letters to Atticus contained such a wealth of detail "concerning the inclinations of leading men, the faults of the generals, and the revolutions in the government" that their reader had little need for a history of the period.[3]

During the chaotic middle period of the first century BC, marked by civil wars and the dictatorship of Gaius Julius Caesar, Cicero championed a return to the traditional republican government. However, his career as a statesman was marked by inconsistencies and a tendency to shift his position in response to changes in the political climate. His indecision may be attributed to his sensitive and impressionable personality; he was prone to overreaction in the face of political and private change. "Would that he had been able to endure prosperity with greater self-control and adversity with more fortitude!" wrote C. Asinius Pollio, a contemporary Roman statesman and historian.[4][5]

Childhood and family

editCicero was born January 3, 106 BC,[6] in Arpinum (modern-day Arpino), a hill town 100 kilometres (62 mi) south of Rome. The Arpinians received Roman citizenship in 188 BC, but had started to speak Latin rather than their native Volscian before they were enfranchised by the Romans.[7] The assimilation of nearby Italian communities into Roman society, which took place during the 2nd and 1st centuries, made Cicero's future as a Roman statesman, orator and writer possible. Although a great master of Latin rhetoric and composition, Cicero was not "Roman" in the traditional sense; he was quite self-conscious of this for his entire life.

During this period in Roman history, if one was to be considered "cultured", it was necessary to be able to speak both Latin and Greek. The Roman upper class often preferred Greek to Latin in private correspondence, recognizing its more refined and precise expressions, and its greater subtlety and nuance. Knowledge about Greek culture and literature was extremely influential for upper class Roman society. When crossing the Rubicon in 49 BC, one of the most symbolic and infamous events in Roman history, Caesar is said to have quoted the Athenian playwright Menander.[8] Greek was already being taught in Arpinum before the city was allied with Rome, which made assimilation into Roman society relatively seamless for the local elite.[9] Cicero, like most of his contemporaries, was also educated in the teachings of the ancient Greek rhetoricians, and most prominent teachers of oratory of the time were themselves Greek.[10] Cicero used his knowledge of Greek to translate many of the theoretical concepts of Greek philosophy into Latin, thus translating Greek philosophical works for a larger audience. He was so diligent in his studies of Greek culture and language as a youth that he was jokingly called the "little Greek boy" by his provincial family and friends. But it was precisely this obsession that tied him to the traditional Roman elite.[11]

Cicero's parents were Marcus Tullius Cicero and Helvia, and he had a brother, Quintus Tullius Cicero, who later married Pomponia, the sister of Cicero's friend Atticus. Cicero's family belonged to the local gentry, domi nobiles, but had no familial ties with the Roman senatorial class. Cicero was only distantly related to one notable person born in Arpinum, Gaius Marius,[12] though he received little political benefit from this connection. In fact, it may have hindered his political aims, as Marius's political allies were defeated in a civil war during the 80s BC, and anyone connected to the Marian regime was viewed as a potential troublemaker.[13]

Cicero's father was a well-to-do eques (knight) with good connections in Rome. Though he was a semi-invalid who could not enter public life, he compensated for this by studying extensively. Although little is known about Cicero's mother, Helvia, it was common for the wives of important Roman citizens to be responsible for the management of the household. Cicero's brother Quintus wrote in a letter that she was a thrifty housewife.[14]

Cicero's cognomen, personal surname, is derived from the Latin for chickpea. Romans often chose down-to-earth personal surnames. Plutarch explains that the name was originally given to one of Cicero's ancestors who had a cleft in the tip of his nose resembling a chickpea. Plutarch adds that Cicero was urged to change this deprecatory name when he entered politics, but refused, saying that he would make Cicero more glorious than Scaurus ("Swollen-ankled") and Catulus ("Puppy").[15]

Studies

editAccording to Plutarch, Cicero was an extremely talented student, whose learning attracted attention from all over Rome,[16] affording him the opportunity to study Roman law under Quintus Mucius Scaevola.[17] In the same way, years later, a young Marcus Caelius Rufus and other young lawyers would study under Cicero; an association of the sort was considered a great honour to both teacher and pupil. He also had the support of his family's patrons, Marcus Aemilius Scaurus and Lucius Licinius Crassus. The latter was a model to Cicero both as an orator and as a statesman.

Cicero's fellow students with Scaevola were Gaius Marius Minor, Servius Sulpicius Rufus (who became a famous lawyer, one of the few whom Cicero considered superior to himself in legal matters), and Titus Pomponius. The latter two became Cicero's friends for life, and Pomponius (who received the cognomen "Atticus" for his philhellenism) would become Cicero's chief emotional support and adviser. "You are a second brother to me, an 'alter ego' to whom I can tell everything," Cicero wrote in one of his letters to Atticus.[18]

In his youth, Cicero tried his hand at poetry, although his main interests lay elsewhere. His poetic works include translations of Homer and the Phaenomena of Aratus, which later influenced Virgil to use that poem in the Georgics. He also wrote, probably during his exile, a poem 'de consulatu suo' (On his Own Consulship), which has been, perhaps unfairly, ridiculed.[19]

In the late 90s and early 80s BC Cicero fell in love with philosophy, which was to have a great role in his life, ultimately adopting Academic Skepticism. He would eventually introduce Greek philosophy to the Romans and create a philosophical vocabulary for it in Latin. The first philosopher he met was the Epicurean philosopher Phaedrus, when he was visiting Rome c. 91 BC. His fellow student at Scaevola's, Titus Pomponius, accompanied him. Titus Pomponius (Atticus), unlike Cicero, would remain an Epicurean for the rest of his life.

In 87 BC, Philo of Larissa, the head of the Academy that was founded by Plato in Athens about 300 years earlier, arrived in Rome. Cicero, "inspired by an extraordinary zeal for philosophy",[20] sat enthusiastically at his feet and absorbed Plato's philosophy, even calling Plato his god. He most admired Plato's moral and political seriousness, but he also respected his breadth of imagination. Cicero nonetheless rejected Plato's Theory of forms.

Shortly thereafter, Cicero met Diodotus, an exponent of Stoicism. Stoicism had already been introduced to Roman society during the previous generation, and it maintained popular appeal among the Romans. Cicero did not completely accept Stoicism's austere philosophy, but he did adopt a modified Stoicism prevalent during the time. Diodotus the Stoic became Cicero's protégé and lived in his house until his death. Diodotus demonstrated a truly Stoic attitude when he continued to study and teach despite losing his sight.[20]

In the years 79–78 BC, Cicero continued his studies while on a tour of Greece, Asia Minor, and Rhodes. Some believed that Cicero left for Greece to avoid the anger of Sulla: according to Plutarch, Sulla was angered by Cicero's defence of Sextus Roscius in the Pro Roscio Amerino of 80 BC (as Cicero's argument challenged the authority of Sulla's freedman, Lucius Cornelius Chrysogonus),[21][22] while it seems that Cicero also criticised Sulla in the lost speech In defence of the women of Arretium sometime in early 79 BC.[23] However, Cicero himself says his departure was to hone his oratorical skills, and in particular to strengthen his body, which at the time was dangerously frail.[24] In Athens, he studied philosophy with Antiochus of Ascalon, the 'Old Academic' and initiator of Middle Platonism.[25] In Asia Minor, he met the leading orators of the region and continued to study with them. Cicero then journeyed to Rhodes to meet with Apollonius Molon, a famous rhetorician who had previously taught Cicero while on a visit to Rome. Molon helped Cicero hone the excesses in his style, as well as train his body and lungs for the demands of public speaking.[26]

Cicero probably took part in the Eleusinian Mysteries as he wrote about them: "For it appears to me that among the many exceptional and divine things your Athens has produced and contributed to human life, nothing is better than those Eleusinian mysteries. For by means of them we have transformed from a rough and savage way of life to the state of humanity, and have been civilized. Just as they are called initiations, so in actual fact we have learned from them the fundamentals of life, and have grasped the basis not only for living with joy but also for dying with a better hope."[27][28]

Marriages

editCicero married Terentia probably at the age of 27, in 79 BC. The marriage, which was a marriage of convenience, was harmonious for some 30 years. Terentia was of patrician background and a wealthy heiress, both important concerns for the ambitious young man that Cicero was at this time. One of her sisters, or a cousin, had been chosen to become a Vestal Virgin – a very great honour. Terentia was a strong-willed woman and (citing Plutarch) "she took more interest in her husband's political career than she allowed him to take in household affairs".[29] She did not share Cicero's intellectual interests nor his agnosticism. Cicero laments to Terentia in a letter written during his exile in Greece that "neither the gods whom you have worshipped with such a devotion nor the men that I have ever served, have shown the slightest sign of gratitude toward us".[30] She was a pious and probably a rather down-to-earth person.

In the 50s BC, Cicero's letters to Terentia became shorter and colder. He complained to his friends that Terentia had betrayed him but did not specify in which sense. Perhaps the marriage simply could not outlast the strain of the political upheaval in Rome, Cicero's involvement in it, and various other disputes between the two. The divorce appears to have taken place in 47 or 46 BC.[31] In 46 or 45 BC,[32] Cicero married a young girl, Publilia, who had been his ward. It is thought that Cicero needed her money, particularly after having to repay the dowry of Terentia, who came from a wealthy family.[33][34] This marriage did not last long. Shortly after the marriage had taken place Cicero's daughter, Tullia, died. Publilia had been jealous of her and was so unsympathetic over her death that Cicero divorced her. Several friends of his, among them Caerellia, a woman who shared Cicero's interest in philosophy, tried to mend the break but he remained adamant.[35]

Tullia and Marcus Minor

editIt is commonly known that Cicero held great love for his daughter Tullia, although his marriage to Terentia was one of convenience. He describes her in a letter to his brother Quintus: "How affectionate, how modest, how clever! The express image of my face, my speech, my very soul."[36] When she suddenly became ill in February 45 BC and died after having seemingly recovered from giving birth to a son in January, Cicero was stunned. "I have lost the one thing that bound me to life" he wrote to Atticus.[35] Atticus told him to come for a visit during the first weeks of his bereavement, so that he could comfort him when his pain was at its greatest. In Atticus' large library, Cicero read everything that the Greek philosophers had written about overcoming grief, "but my sorrow defeats all consolation."[37] Caesar and Brutus sent him letters of condolence. So did his old friend and colleague, the lawyer Servius Sulpicius Rufus. He sent an exquisite letter that posterity has much admired, full of subtle, melancholy reflection on the transiency of all things.[38][39]

After a while, he withdrew from all company to complete solitude in his newly acquired villa in Astura. It was in a lonely spot, but not far from Neapolis (modern Naples). For several months he just walked in the woods, crying. "I plunge into the dense wild wood early in the day and stay there until evening", he wrote to Atticus.[40] Later he decided to write a book for himself on overcoming grief. This book, Consolatio, was highly appreciated in antiquity (and made an immense impression on St. Augustine), but is unfortunately lost.[41] A few fragments have survived, among them the poignant: "I have always fought against Fortune, and beaten her. Even in exile I played the man. But now I yield, and throw up my hand."[42] He also planned to erect a small temple to the memory of Tullia, "his incomparable daughter." But he dropped this plan after a year, for reasons unknown.[43]

Cicero hoped that his son Marcus would become a philosopher like him, but that was wishful thinking. Marcus himself wished for a military career. He joined the army of Pompey in 49 BC and after Pompey's defeat at Pharsalus 48 BC, he was pardoned by Caesar. Cicero sent him to Athens to study as a disciple of the Peripatetic philosopher Kratippos in 48 BC, but he used this absence from "his father's vigilant eye" to "eat, drink and be merry."[44]

After his father's murder, Marcus joined the army of the Liberatores but was later pardoned by Augustus. Augustus' bad conscience for having put Cicero on the proscription list during the Second Triumvirate led him to aid considerably Marcus Minor's career. He became an augur, and was nominated consul in 30 BC together with Augustus, and later appointed proconsul of Syria and the province of Asia.[45]

Political and social thought

editCicero's vision for the Republic was not simply the maintenance of the status quo, nor was it a straightforward desire to revitalise what many, such as Sallust, term the "moral degradation" of the republican system. Cicero envisioned a Rome ruled by a selfless nobility of successful individuals determining the fate of the nation via consensus in the Senate. Thanks to his equestrian and country background Cicero had a broader outlook, less marred by self-interest than those of the patricians of Rome.

Cicero aspired to a republican system dominated by a ruling aristocratic class of men, "who so conducted themselves as to win for their policy the approval of all good men." Further, he sought a concordia ordinum, an alliance between the senators and the equites. This "harmony between the social classes," which he later developed into a consensus omnium bonorum to include tota Italia (all citizens of Italy), demonstrated Cicero's foresight as a statesman. He understood that fundamental change to the organization and the distribution of power within the Republic was required to secure its future. Cicero believed "the best men" would institute large-scale reforms which were contrary to their interests as the ruling oligarchy. Cicero believed that only "some sort of free state" would engender stability and justice.[46]

Links with the equestrian class, combined with his status as a novus homo meant that Cicero was isolated from the optimates. Thus, it is not surprising that Cicero envisioned a "selfless nobility of successful individuals" rather than the patrician-dominated system. Senators had made huge profits by exploiting the provinces. Repeatedly, the oligarchy had proved to be short-sighted, reactionary and "operating with restricted and outmoded institutions that could no longer cope with the vast territories containing multifarious populations that was Rome at this point of its history". The repeated failings of the oligarchy were not only due to the leading patricians like Crassus and Hortensius, but also to the influx of conservative equites into the Senate's ranks.

The combination of the Roman governing system, used by the oligarchy to selfishly maximize economic exploitation, and the introduction of the business minded equites, increased the plundering of resources in the Empire. The large-scale extortion destabilized the political system further, which was continuously under pressure by both foreign wars and from the populares. Moreover, this period of Roman history was marked by constant in-fighting between the senators and the equites over political power and control of the courts. The problem arose because Sulla originally enfranchised the equites, but then these privileges were soon removed after he stepped down from office. Cicero, as an eques, naturally backed their claims to participate in the legal process; moreover, the constant conflict was incompatible with his vision of a concordia ordinum. The conflict between the two classes showed no signs of short-term resolution. The ruling class for over a century had showed nothing of "selfless service" to the Republic and through their actions only undermined its stability, contributing to the creation of a society ripe for revolution.

The establishment of individual power bases both within Rome and in the provinces undermined Cicero's guiding principle of a free state, and thus the Roman Republic itself. This factionalised the Senate into cliques, which constantly engaged each other for political advantage. These cliques were the optimates, led by such figures as Cato, and in later years Pompey, and the populares, led by such men as Julius Caesar and Crassus. Although the optimates were generally republicans, some leaders of the optimates had distinctly dictatorial ways. Caesar, Crassus and Pompey were at one time the head of the First Triumvirate, which directly conflicted with the republican model as it did not comply with the system of holding a consulship for one year only. Cicero's vision for the Republic could not succeed if the populares maintained their position of power. Cicero did not envisage widespread reform, but a return to the "golden age" of the Republic. Despite Cicero's attempts to court Pompey over to the republican side, he failed to secure either Pompey's genuine support or peace for Rome.

Death

editAlthough Cicero had not been a conspirator in Julius Caesar's assassination, he had sympathized with the assassins. This, plus a personal rivalry with Mark Antony, resulted in Cicero being added to the list of proscribed persons during the proscriptions of the Second Triumvirate. Reportedly, Octavian argued for two days against Cicero being added to the list.[47]

Among the proscribed, Cicero was one of the most viciously and doggedly hunted. Other victims included the tribune Salvius, who, after siding with Antony, moved his support directly and fully to Cicero. Cicero was viewed with sympathy by a large segment of the public, and many people refused to report that they had seen him. He was caught December 7, 43 BC leaving his villa in Formiae in a litter going to the seaside from where he hoped to embark on a ship to Macedonia.[48] When the assassins arrived his own slaves said they had not seen him, but he was given away by Philologus, a freed slave of his brother Quintus Cicero.[48]

Cicero's last words were said to have been, "There is nothing proper about what you are doing, soldier, but do try to kill me properly."[citation needed] He was decapitated by his pursuers. Once discovered, he bowed to his captors, leaning his head out of the litter in a gladiatorial gesture to ease the task. By baring his neck and throat to the soldiers, he was indicating that he wouldn't resist. His hands were cut off as well and nailed and displayed along with the head on the Rostra in the Forum Romanum according to the tradition of Marius and Sulla, both of whom had displayed the heads of their enemies in the Forum. He was the only victim of the Triumvirate's proscriptions to be displayed in that manner. According to Cassius Dio[49] (in a story often mistakenly attributed to Plutarch), Antony's wife Fulvia took Cicero's head, pulled out his tongue, and jabbed it repeatedly with her hairpin in final revenge against Cicero's power of speech.[50]

Cicero's son, Marcus Tullius Cicero Minor, during his year as a consul in 30 BC, avenged his father's death somewhat when he announced to the Senate Mark Antony's naval defeat at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC by Octavian and his capable commander-in-chief Agrippa. In the same meeting the Senate voted to prohibit all future Antonius descendants from using the name Marcus.

Later on, Octavian came upon one of his grandsons reading a book by Cicero. The boy tried to conceal it, fearing his grandfather's reaction. Octavian (now called Augustus) took the book from him, read a part of it, and then handed the volume back, saying: "He was a learned man, dear child, a learned man who loved his country".[51]

Criticism

editCicero's self-promoted image presents him as a virtuous hero of the patrician republic, but in his own lifetime he was criticized severely by the populares and their champions. A diatribe attributed to Sallust called Contra Ciceronem and also known as the Invective Against Cicero paints a picture of him that is much different than the well-known image of him as man.

In the invective the author first cricitizes him for arrogantly acting like a native patrician, when in fact his family was from a town far away from the city and he himself was a novo homo and that he was related not to Republicans but to the family of Marius.[52] Then he is accused of being sexually depraved and specifically it says he engaged in a corrupt sexual relationship with Marcus Piso.[53] It says he was a gluttonous gourmand.[54] It then says his wife committed sacrileges and perjury and implies that he committed incest with his daughter.[55] It accuses him of allowing his wife to meddle in politics and receiving her as his own consultant in his own political business.[56] It accuses him of setting up courts to convict his political enemies and then forcing them to give him money and property, including luxurious villas at Pompeii and Tusculum and his house in Rome.[57] The invective says if he disputes this then to explain how he could have possibly earned the money required by inheritance or legal fees.[58] The invective goes on to accuse him of blackmailing patricians into giving him money or else he would associate them to Catiline.[59] The invective says that he is "suppliant to his enemies, insolent to his friends, in one party one day, in another the next, loyal to none".[60] It accuses him of having the Lex Porcia repealed and then exploiting that by extorting Roman citizens into giving him money by threats in the court.[61]

Legacy

editAfter the civil war, Cicero recognised that the end of the Republic was almost certain. He stated that "the Republic, the Senate, the law courts are mere ciphers and that not one of us has any constitutional position at all." The civil war had destroyed the Republic. It wreaked destruction and decimated resources throughout the Roman Empire. Julius Caesar's victory had been absolute. Caesar's assassination failed to reinstate the Republic, despite further attacks on the Romans’ freedom by "Caesar’s own henchman, Mark Antony." His death only highlighted the stability of "one man rule" by the ensuing chaos and further civil wars that broke out with Caesar's murderers, Brutus and Cassius, and finally between his own supporters, Mark Antony and Octavian.

Cicero remained the "Republic's last true friend" as he spoke out for his ideals and of the libertas (freedom) the Romans enjoyed for centuries. Cicero's vision had some fundamental flaws. It harked back to a "golden age" that may never have existed. Cicero's idea of the concordia ordinum was too idealistic. Also, Roman institutions had failed to keep pace with Rome's enormous expansion. The Republic had reached such a state of disrepair that regardless of Cicero's talents and passion, Rome lacked "persons loyal to [the Republic] to trust with armies." Cicero lacked the political power and any military skill or resources, to enforce his ideal. To enforce republican values and institutions was ipso facto contrary to republican values. He also failed to a certain extent to recognize the real power structures that operated in Rome.

Popular culture

editModern fiction, listed in order of publication

edit- Julius Caesar (1623), by William Shakespeare; probably performed 1599 but unpublished until the First Folio

- Ides of March (1948), an epistolary novel by Thornton Wilder

- A Pillar of Iron (1965), a fictionalized biography by Taylor Caldwell

- Masters of Rome series (1990-2007), by Colleen McCullough; Cicero first appears as a precocious young boy in The Grass Crown (1991)

- Roma Sub Rosa series (1991–2005), by Steven Saylor

- Severance (2006), a short monologue by Robert Olen Butler that imagines Cicero's last thoughts

- Imperium (2006), Lustrum (2009; published in the US as Conspirata), and Dictator (2015), a trilogy of novels about Cicero's political career by Robert Harris

Film and television

edit- Imperium: Augustus, a British-Italian film (2003), also shown as Augustus The First Emperor in some countries, where Cicero (played by Gottfried John) appears in several vignettes.

- In the 2005 ABC miniseries Empire, Cicero (played by Michael Byrne) appears as a supporter of Octavius. This portrayal deviates sharply from history, as Cicero survives the civil war to witness Octavius assume the title of princeps.

- The HBO/BBC2 TV series Rome features Marcus Tullius Cicero prominently; the role is played by David Bamber. The portrayal broadly adheres to the historical record, reflecting Cicero's political indecision and continued switching of allegiances between the various factions in Rome's civil war. A disparity occurs in his assassination, which occurs in an orchard rather than on the road to the sea. The TV series also depicts Cicero's assassination at the hands of the fictionalized Titus Pullo, though the historical Titus Pullo was not Cicero's actual killer.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Rawson, E.: Cicero, a portrait (1975) p. 303

- ^ Haskell, H.J.: This was Cicero (1964) pp. 300–01

- ^ Cornelius Nepos, Atticus 16, trans. John Selby Watson.

- ^ Haskell, H.J.:"This was Cicero" (1964) p. 296

- ^ Castren and Pietilä-Castren: "Antiikin käsikirja" /"Handbook of antiquity" (2000) p. 237

- ^ "UPI Almanac for Thursday, Jan. 3, 2019". United Press International. January 3, 2019. Archived from the original on January 3, 2019. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

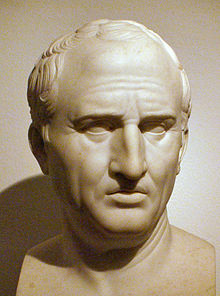

Roman philosopher Cicero in 106 B.C

- ^ Rawson, E.: Cicero, a portrait (1975) p. 1

- ^ Plutarch: "Lives" p. 874

- ^ Rawson, E.: "Cicero, a portrait" (1975) p. 7.

- ^ Rawson, E.: "Cicero, a portrait" (1975) p. 8

- ^ Everitt, A.: "Cicero: The Life and Times of Rome's Greatest Politician" (2001) p. 35

- ^ Rawson, E. "Cicero, a portrait" (1975) pp. 2–3

- ^ Rawson, E.: "Cicero, a portrait" (1975) p. 17

- ^ Rawson, E.: Cicero, a portrait (1975) pp. 5–6; Cicero, Ad Familiares 16.26.2 (Quintus to Cicero)

- ^ Plutarch, Cicero 1.3–5

- ^ Plutarch, Cicero 2.2

- ^ Plutarch, Cicero 3.2

- ^ Rawson, Elizabeth: "Cicero, a portrait" (1975) pp. 14–15

- ^ "Cicero: De consulatu suo".

- ^ a b Rawson: "Cicero, a portrait" (1975) p. 18

- ^ Plutarch, Cicero 3.2–5

- ^ c.f. Cicero, de Officiis 2.51

- ^ Cic. Caec. 97.

- ^ Cicero, Brutus 313–14

- ^ Cicero, Brutus 315

- ^ Cicero, Brutus 315–17

- ^ Gagnéé, Renaud (2009-10-01). "Mystery Inquisitors: Performance, Authority, and Sacrilege at Eleusis". Classical Antiquity. 28 (2): 211–247. doi:10.1525/CA.2009.28.2.211. ISSN 0278-6656.

- ^ "The Eleusinian Mysteries: The Rites of Demeter". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ^ Rawson, E.: "Cicero, a portrait" (1975) p. 25

- ^ Haskell, H.J.: "This was Cicero" (1964) p. 96

- ^ Susan Treggiari, Terentia, Tullia and Publilia: the women of Cicero's family, London: Routledge, 2007, pp. 129ff.

- ^ Treggiari, op. cit., p. 133

- ^ Rawson, E.: Cicero p. 225

- ^ Plutarch (1967). Plutarch's Lives. Translated by Perrin, Bernadotte. London; Cambridge, Mass.: W. Heinemann ; Harvard University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-674-99114-9. OCLC 264953938. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

His wife Terentia brought him besides a dowry of a hundred thousand denarii, and he received a bequest which amounted to ninety thousand.

- ^ a b Haskell, H.J.: "This was Cicero" (1964) p. 249

- ^ Haskell H.J.: This was Cicero, p. 95

- ^ Cicero, Letters to Atticus, 12.14. Rawson, E.: Cicero p. 225

- ^ Rawson, E.: Cicero p. 226

- ^ Cicero, Samtliga brev/Collected letters ad Fam. 4, 5 and 6

- ^ Haskell, H.J.: This was Cicero, p. 250

- ^ Rawson, E.: Cicero, pp. 225–27

- ^ Haskell, H.J.: This was Cicero p. 251

- ^ Rawson, E.: Cicero, p. 250

- ^ Haskell, H.J.: This was Cicero (1964) pp. 103–04

- ^ Paavo Castren & L. Pietilä-Castren: Antiikin käsikirja/Encyclopedia of the Ancient World

- ^ James Leigh Strachan-Davidson. Rome. 1894, p. 427

- ^ Plutarch, Cicero 46.3–5

- ^ a b Haskell, H.J.: This was Cicero (1964) p. 293

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History 47.8.4

- ^ Everitt, A.: Cicero, A turbulent life (2001)

- ^ Plutarch, Cicero, 49.5

- ^ Bailey, D. R. Shackleton. Letters to Quintus and Brutus. Letter Fragments. Letter to Octavian. Invectives. Handbook of Electioneering. Cicero Volume XXVIII, Loeb Classical Library 462, 2002. p. 367

- ^ Bailey, D. R. Shackleton. Letters to Quintus and Brutus. Letter Fragments. Letter to Octavian. Invectives. Handbook of Electioneering. Cicero Volume XXVIII, Loeb Classical Library 462, 2002. p. 367

- ^ Bailey, D. R. Shackleton. Letters to Quintus and Brutus. Letter Fragments. Letter to Octavian. Invectives. Handbook of Electioneering. Cicero Volume XXVIII, Loeb Classical Library 462, 2002. p. 367

- ^ Bailey, D. R. Shackleton. Letters to Quintus and Brutus. Letter Fragments. Letter to Octavian. Invectives. Handbook of Electioneering. Cicero Volume XXVIII, Loeb Classical Library 462, 2002. p. 367

- ^ Bailey, D. R. Shackleton. Letters to Quintus and Brutus. Letter Fragments. Letter to Octavian. Invectives. Handbook of Electioneering. Cicero Volume XXVIII, Loeb Classical Library 462, 2002. p. 369

- ^ Bailey, D. R. Shackleton. Letters to Quintus and Brutus. Letter Fragments. Letter to Octavian. Invectives. Handbook of Electioneering. Cicero Volume XXVIII, Loeb Classical Library 462, 2002. p. 371

- ^ Bailey, D. R. Shackleton. Letters to Quintus and Brutus. Letter Fragments. Letter to Octavian. Invectives. Handbook of Electioneering. Cicero Volume XXVIII, Loeb Classical Library 462, 2002. p. 371

- ^ Bailey, D. R. Shackleton. Letters to Quintus and Brutus. Letter Fragments. Letter to Octavian. Invectives. Handbook of Electioneering. Cicero Volume XXVIII, Loeb Classical Library 462, 2002. p. 369

- ^ Bailey, D. R. Shackleton. Letters to Quintus and Brutus. Letter Fragments. Letter to Octavian. Invectives. Handbook of Electioneering. Cicero Volume XXVIII, Loeb Classical Library 462, 2002. p. 369

- ^ Bailey, D. R. Shackleton. Letters to Quintus and Brutus. Letter Fragments. Letter to Octavian. Invectives. Handbook of Electioneering. Cicero Volume XXVIII, Loeb Classical Library 462, 2002. p. 371

References

edit- Bailey, D. R. Shackleton.Letters to Quintus and Brutus. Letter Fragments. Letter to Octavian. Invectives. Handbook of Electioneering. Cicero Volume XXVIII, Loeb Classical Library 462, 2002.

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius, Cicero's letters to Atticus, Vol, I, II, IV, VI, Cambridge University Press, Great Britain, 1965

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius, Latin extracts of Cicero on Himself, translated by Charles Gordon Cooper, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1963

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius, Selected Political Speeches, Penguin Books Ltd, Great Britain, 1969

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius, Selected Works, Penguin Books Ltd, Great Britain, 1971

- Everitt, Anthony 2001, Cicero: the life and times of Rome's greatest politician, Random House, hardback, 359 pages, ISBN 0-375-50746-9

- Cowell, Cicero and the Roman Republic, Penguin Books Ltd, Great Britain, 1973

- Haskell, H.J.: (1946) This was Cicero, Fawcett publications, Inc. Greenwich, CN

- Gibbon, Edward (1793). The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire., The Modern Library (2003), ISBN 0-375-75811-9. Edited, Abridged, and with a Critical Foreword by Hans-Friedrich Mueller.

- Gruen, Erich, The last Generation of the Roman Republic, University of California Press, US, 1974

- March, Duane A., "Cicero and the 'Gang of Five'," Classical World, volume 82 (1989) 225–234

- Plutarch, Fall of the Roman Republic, Penguin Books Ltd, Great Britain, 1972

- Rawson, Elizabeth (1975) Cicero, A portrait, Allen Lane, London ISBN 0-7139-0864-5

- Rawson, Elizabeth, Cicero, Penguin Books Ltd, Great Britain, 1975

- Scullard, H.H. From the Gracchi to Nero, University Paperbacks, Great Britain, 1968

- Smith, R.E., Cicero the Statesman, Cambridge University Press, Great Britain, 1966

- Strachan-Davidson, J.L., Cicero and the Fall of the Roman Republic, University of Oxford Press, London, 1936

- Taylor, H. (1918). Cicero: A sketch of his life and works. Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co.

Further reading

edit- Francis A. Yates (1974). The Art of Memory, University of Chicago Press, 448 pages, Reprint: ISBN 0-226-95001-8

- Taylor Caldwell (1965), A Pillar of Iron, Doubleday & Company, Reprint: ISBN 0-385-05303-7

External links

edit- General:

- Works by Cicero:

- Works by Cicero at Project Gutenberg

- Perseus Project (Latin and English): Classics Collection (see: M. Tullius Cicero)

- The Latin Library (Latin): Works of Cicero

- UAH (Latin, with translation notes): Cicero Page

- De Officiis, translated by Walter Miller

- Cicero's works: text, concordances and frequency list

- Biographies and descriptions of Cicero's time:

- At Project Gutenberg

- Plutarch's biography of Cicero contained in the Parallel Lives

- Life of Cicero by Anthony Trollope, Volume I – Volume II

- Cicero by Rev. W. Lucas Collins (Ancient Classics for English Readers)

- Roman life in the days of Cicero by Rev. Alfred J. Church

- Social life at Rome in the Age of Cicero by W. Warde Fowler

- At Heraklia website

- Dryden's translation of Cicero from Plutarch's Parallel Lives

- At Middlebury College website

- At Project Gutenberg

- SORGLL: Cicero, In Catilinam I; I,1-3, read by Robert Sonkowsky