This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The Cry of Pugad Lawin (Filipino: Sigaw sa Pugad Lawin, Spanish: Grito de Pugad Lawin) was the beginning of the Philippine Revolution against the Spanish Empire.[1]

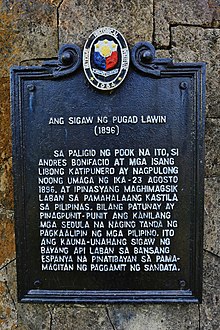

NHCP Marker in Pugad Lawin Shrine | |

| Native name | Sigaw ng Pugad Lawin |

|---|---|

| Date | August 23, 1896 (exact date disputed) |

| Venue | Province of Manila, Captaincy General of the Philippines, exact location uncertain. See here for more info. |

| Organised by | |

| Outcome | Start of the Philippine Revolution

|

In late August 1896, members of the Katipunan[a] led by Andrés Bonifacio revolted somewhere around Caloocan, which included parts of the present-day Quezon City.[2][3]

Originally the term cry referred to the first clash between the Katipuneros and the Civil Guards (Guardia Civil). The cry could also refer to the tearing up of community tax certificates (cédulas personales) in defiance of their allegiance to Spain. This was literally accompanied by patriotic shouts.[4]

Because accounts of the event vary, the exact date and place of the event is unknown.[3][4] From 1908 until 1963, the event was thought to have occurred on August 26 in Balintawak. In 1963, the Philippine government declared August 23 to be the date of the event in Quezon City.[5][4]

Characterization of the event

editThe term "Cry" is translated from the Spanish el grito de rebelion (cry of rebellion) or el grito for short. Thus the Grito de Balintawak is comparable to Mexico's Grito de Dolores (1810). However, el grito de rebelion strictly refers to a decision or call to revolt. It does not necessarily connote shouting, unlike the Filipino sigaw.[3][4]

Accounts of the Cry

editGuillermo Masangkay

editOn August 26, a big meeting was held in Balintawak, at the house of Apolonio Samson, then cabeza of that barrio of Caloocan. Among those who attended, I remember, were Bonifacio, Emilio Jacinto, Aguedo del Rosario, Tomas Remigio, Briccio Pantas, Teodoro Plata, Pio Valenzuela, Enrique Pacheco, and Francisco Carreon. They were all leaders of the Katipunan and composed the board of directors of the organization. Delegates from Bulacan, Cabanatuan, Cavite, and Morong were also present.[citation needed]

At about nine o'clock in the morning of August 26, the meeting was opened with Andres Bonifacio presiding and Emilio Jacinto acting as secretary. The purpose was to discuss when the uprising was to take place. Teodoro Plata, Briccio Pantas, and Pio Valenzuela were all opposed to starting the revolution too early...Andres Bonifacio, sensing that he would lose the discussion then, left the session hall and talked to the people, who were waiting outside for the result of the meeting of the leaders. He told the people that the leaders were arguing against starting the revolution early, and appealed to them in a fiery speech in which he said:"You remember the fate of our countrymen who were shot in Bagumbayan. Should we return now to the towns, the Spaniards will only shoot us. Our organization has been discovered and we are all marked men. If we don't start the uprising, the Spaniards will get us anyway. What then, do you say?"[6]

"Revolt!" the people shouted as one.[6]

Bonifacio then asked the people to give a pledge that they were to revolt. He told them that the sign of slavery of the Filipinos were (sic) the cedula tax charged each citizen. "If it is true that you are ready to revolt... I want to see you destroy your cedulas. It will be a sign that all of us have declared our severance from the Spaniards.[7]

The Cry of Balintawak occurred on August 26, 1896. The Cry, defined as that turning point when the Filipinos finally refused Spanish colonial dominion over the Philippine Islands. With tears in their eyes, the people as one man, pulled out their cedulas and tore them into pieces. It was the beginning of the formal declaration of the separation from Spanish rule."Long Live the Philippine Republic!", the cry of the people. An article from The Sunday Tribune Magazine on August 21, 1932 featured the statements of the eyewitness account by Katipunan General Guillermo Masangkay, "A Katipunero Speaks". Masangkay recounts the "Cry of Balintawak", stating that on August 26, 1896, a big meeting was held in Balintawak at the house of Apolonio Samson, then the cabeza of that barrio of Caloocan. At about nine o'clock in the morning of August 26, the meeting was opened with Andres Bonifacio presiding and Emilio Jacinto acting as Secretary. In August 1896, after the Katipunan was discovered, Masangkay joined Bonifacio, Emilio Jacinto, and others in a clandestine meeting held on the 26th of that month at Apolonio Samson’s house in Caloocan.

Initially, the leaders of the movement quarreled over strategy and tactics, and many of its members questioned the wisdom of an open rebellion due to the lack of arms and logistical support. However, after Bonifacio’s intense and convincing speech, everyone destroyed their cedulas to symbolize their defiance towards Spain and, together, raised the cry of “Revolt".[4]

Pio Valenzuela

editIn 1936, Pio Valenzuela, along with Briccio Pantas and Enrique Pacheco said (in English translation) "The first Cry of the revolution did not happen in Balintawak where the monument is, but in a place called Pugad Lawin." In 1940, a research team of a forerunner of the National Historical Institute (NHI) which included Valenzuela, identified the location as part of sitio Gulod, Banlat, Kalookan City. IN 1964, the NHI described this location as the house of Tandang Sora.[8]

The first place of refuge of Andres Bonifacio, Emilio Jacinto, Procopio, Bonifacio, Teodoro Plata, Aguedo del Rosario, and myself was Balintawak, the first five arriving there on August 19, and I on August 20, 1896. The first place where some 500 members of the Katipunan met on August 22, 1896, was the house and yard of Apolonio Samson at Kangkong. Aside from the persons mentioned above, among those who were there were Briccio Pantas, Alejandro Santiago, Ramon Bernardo, Apolonio Samson, and others. Here, views were only exchanged, and no resolution was debated or adopted. It was at Pugad Lawin, the house, store-house, and yard of Juan Ramos, son of Melchora Aquino, where over 1,000 members of the Katipunan met and carried out considerable debate and discussion on August 23, 1896. The discussion was on whether or not the revolution against the Spanish government should be started on August 29, 1896... After the tumultuous meeting, many of those present tore their cedula certificates and shouted "Long live the Philippines! Long live the Philippines!"[9]

Santiago Alvarez

editSantiago Alvarez regarding the Cry of Balintawak flaunted specific endeavors, as stated:

We started our trek to Kangkong at about eleven that night. We walked through the rain over dark expanses of muddy meadows and fields. Our clothes drenched and our bodies numbed by the cold wind, we plodded wordlessly. It was nearly two in the morning when we reached the house of Brother Apolonio Samson in Kangkong. We crowded into the house to rest and warm ourselves. We were so tired that, after hanging our clothes out to dry, we soon feel asleep. The Supremo began assigning guards at five o'clock the following morning, Saturday 22 August 1896. He placed a detachment at the Balintawak boundary and another at the backyard to the north of the house where we were gathered. No less than three hundred men assembled at the bidding of the Supremo Andres Bonifacio. Altogether, they carried assorted weapons, bolos, spears, daggers, a dozen small revolvers and a rifle used by its owner, one Lieutenant Manuel, for hunting birds. The Supremo Bonifacio was restless because of fear of sudden attack by the enemy. He was worried over the thought that any of the couriers carrying the letter sent by Emilio Jacinto could have been intercepted; and in that eventuality, the enemy would surely know their whereabouts and attack them on the sly. He decided that it was better to move to a site called Bahay Toro. At ten o'clock that Sunday morning, 23 August 1896 we arrived at Bahay Toro. Our member had grown to more than 500 and the house, yard, and warehouse of Cabesang Melchora was getting crowded with us Katipuneros. The generous hospitality of Cabesang Melchora was no less than that of Apolonio Samson. Like him, she also opened her granary and had plenty of rice pounded and animals slaughtered to feed us. The following day, Monday, 24 August, more Katipuneros came and increased our number to more than a thousand. The Supremo called a meeting at ten o'clock that morning inside Cabesang Melchora's barn. Flanking him on both sides at the head of the table were Dr. Pio Valenzuela, Emilio Jacinto, Briccio Pantas, Enrique Pacheco, Ramon Bernardo, Pantelaon Torres, Francisco Carreon, Vicente Fernandez, Teodoro Plata, and others. We were so crowded that some stood outside the barn. The following matters were approved at the meeting:

- An uprising to defend the people's freedom was to be started at midnight of Saturday, 29 August 1896;

- To be on a state of alert so that the Katipunan forces could strike should the situation arise where the enemy was at a disadvantage. Thus, the uprising could be started earlier than the agreed time of midnight of 29 August 1896 should a favorable opportunity arise at that date. Everyone should steel himself and be resolute in the struggle that was imminent; and

- The immediate objective was the capture of Manila.

After the adjournment of the meeting at twelve noon, there were tumultuous shouts of "Long live the Sons of the People!"[10]

Asserted dates and venues

editVarious accounts give differing dates and places for the Cry of Pugad Lawin. An officer of the Spanish guardia civil, Lt. Olegario Diaz, stated that the Cry took place in Balintawak on August 25, 1896. Historian Teodoro Kalaw in his 1925 book The Filipino Revolution wrote that the event took place during the last week of August 1896 at Kangkong, Balintawak. Santiago Alvarez, a "Katipunero" and son of Mariano Alvarez, the leader of the Magdiwang faction in Cavite, stated in 1927 that the Cry took place in Bahay Toro, now in Quezon City on August 24, 1896. Pío Valenzuela, a close associate of Andrés Bonifacio, declared in 1948 that it happened in Pugad Lawin on August 23, 1896. Historian Gregorio Zaide stated in his books in 1954 that the "Cry" happened in Balintawak on August 26, 1896.[7] Fellow historian Teodoro Agoncillo wrote in 1956 that it took place in Pugad Lawin on August 23, 1896, based on Pío Valenzuela's statement. Accounts by historians Milagros Guerrero, Emmanuel Encarnacion and Ramon Villegas claim the event to have taken place in Tandang Sora's barn in Gulod, Barrio Banlat, Caloocan (now part of Quezon City).[11][12]

Some of the apparent confusion is in part due to the double meanings of the terms Balintawak and Caloocan. At the turn of the century. Balintawak referred both to a specific place in modern Caloocan and a wider area which included parts of modern Quezon City. Similarly, Caloocan referred to modern Caloocan and also a wider area which included modern Quezon City and part of modern Pasig. Pugad Lawin, Pasong Tamo, Kangkong and other specific places were all in "greater Balintawak", which was in turn part of "greater Caloocan".[3][4]

| Person | Place | Date |

|---|---|---|

| L.T. Olegario Diaz | Balintawak | August 25, 1896 |

| Teodoro Kalaw | Kangkong, Balintawak | Last week of August |

| Santiago Alvarez | Bahay Toro | August 24, 1896 |

| Pio Valenzuela | Pugad Lawin | August 23, 1896 |

| Gregorio Zaide | Balintawak | August 26, 1896 |

| Teodoro Agoncillo (according to statements of Valenzuela) | Pugad Lawin | August 23, 1896 |

| Research (Milagros Guerrero, Emmanuel Encarnacion, Ramon Villegas) | Tandang Sora's barn in Gulod, Banlat | August 24, 1896 |

Prior events

editThese events vitalized the unity of the Filipino People and brought "thirst" for independence. The Cry of the Rebellion in Pugad Lawin, marked the start of the Philippine Revolution in 1896 which eventually led to Independence of the country in 1898.

Cavite Mutiny

editOn January 20, 1872, about 200 Filipino military personnel of Fort San Felipe Arsenal in Cavite, Philippines, staged a mutiny which in a way led to the Philippine Revolution in 1896. The 1872 Cavite Mutiny was precipitated by the removal of long-standing personal benefits to the workers such as tax (tribute) and forced labor exemptions on order from the Governor General Rafael de Izquierdo.

Izquierdo replaced Governor General Carlos Maria de la Torre some months before in 1871 and immediately rescinded Torre’s liberal measures and imposed his iron-fist rule. He was opposed to any hint of reformist or nationalistic movements in the Philippines. He was in office for less than two years, but he will be remembered for his cruelty to the Filipinos and the barbaric execution of the three martyr-priests blamed for the mutiny: Fathers Mariano Gomez, Jose Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora, later collectively called “Gomburza.”

Izquierdo used the mutiny to implicate Gomburza and other notable Filipinos known for their liberal leanings.

The three priests were stripped of their albs, and with chained hands and feet were brought to their cells after their sentence. Gomburza became a rallying catchword for the down-trodden Filipinos seeking justice and freedom from Spain.

It is well to remember that the seeds of nationalism that was sown in Cavite blossomed to the Philippine Revolution and later to the Declaration of Independence by Emilio Aguinaldo which took place also in Cavite. 1872 Cavite Mutiny paved way for a momentous 1898, it was a glorious event before we came across to victory.

[15]

Martyrdom of the Gomburza

editThe execution of the three Filipino priest, Mariano Gomez, Jose Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora, who were linked by the Spanish friars as the masterminds of the Filipino insurgency in Cavite. They were prominent Filipino priests charged with treason and sedition. The Spanish clergy connected the priest to the mutiny as part of a conspiracy to stifle the movement of secular priests who desired to have their own parishes instead of being assistants to the regular friars.

Father Mariano Gomez, an old man in his mid-‘70, Chinese-Filipino, born in Cavite. He held the most senior position of the three as Archbishop’s Vicar in Cavite. He was truly nationalistic and accepted the death penalty calmly as though it were his penance for being pro-Filipinos.

Father José Burgos is a Spanish descent, born in the Philippines. He was a parish priest of the Manila Cathedral and had been known to be close to the liberal Governor General de la Torre. He was 35 years old at that time and was active and outspoken in advocating the Filipinization of the clergy.

Father Jacinto Zamora is a 37 years old, was also Spanish, born in the Philippines. He was the parish priest of Marikina and was known to be unfriendly to and would not countenance any arrogance or authoritative behavior from Spaniards coming from Spain. February 17, 1872 in an attempt of the Spanish government to instill fear among the Filipinos so that they may never commit such daring act again, the Gomburza were executed. This event was tragic but served as one of the moving forces that shaped Filipino nationalism.

[16][17][18]

Propaganda Movements and other Peaceful Campaign for Reforms

editFor more than three centuries the Spanish colonizers became too abusive of their power, force labor, unjustifiable collection of taxes, and deprivation of education brought about centralised idea of independence to the majority of Filipinos. Political and social reforms then were sought through writings themed on liberalism, honoring rights of the Filipinos, defense against violence and injustices, and sovereignty for the aspirations of the people.

From 1880 to 1896 propaganda movements became expansive, though it didn't achieve its purpose for reforms it fostered a sense of nationalism among Filipinos.

Noli Me Tángere and El filibusterismo are some of the literary works written by Jose Rizal, who is one of the many ilustrados, together with the other prominent reformist Graciano López Jaena, Mariano Ponce and Marcelo H. del Pilar who aimed on uniting the whole country, and eventually to achieve independence. It was until the latter part of the 1890s when the peaceful movement was shifted to bloody revolts led by Andres Bonifacio who believe that peaceful reforms won't make any change to the corrupt Spaniards, thus initiating the first phase of revolution after the tearing of cedulas at the Cry of Pugadlawin

Jose P. Rizal's Exile in Dapitan

editIn June 26, 1892, very excitement was caused among to the Filipinos. His popularity feared the Spaniards, and as they notice to his every moves - all houses where he had been were searched and the Filipinos seen in his company were suspected. As he had planned, on July 3, 1892 he founded the La Liga Filipina in the house of Doroteo Ongjunco in Tondo, Manila. Four days after the civic organization's foundation, Jose Rizal was arrested by the Spanish authorities on four grounds: First, he published an anti-Catholic and anti-friar books and articles. Second, having in possession a bundle of handbills, the Pobres Frailes, in which violates the advocacies of the Spanish orders. Third for dedicating his novel, El Filibusterismo to the three “traitors” (Gomez, Burgos and Zamora) and for giving an highlights to the novel's title page that “the only salvation for the Philippines was separation from the Spain". And last, had a simply criticizing the religion and aiming for its exclusion from the Filipino culture.

[19]

Foundation and the Discovery of the Katipunan

editAfter the disbandment of the La Liga FILIPINA, some of its former members, spearheaded by Andres Bonifacio established the Katipunan, with its goal of independence from Spain. The Katipunan led by Andres Bonifacio started the revolution preceded by the Cry of Balintawak.

The KKK was revealed by Father Mariano Gil who was disgusted over the governor's attitude, next ran to the military governor of Manila, General Echaluce, and revealed what he knew about the Katipunan. But Echaluce, did not believe him, instead he took precautions to make Manila safe from any disturbances. At almost the same time, an unfortunate event incident happened between two Katipuneros that are working in the Spanish-owned Diario de Manila. Apolonio de la Cruz and Teodoro Patiño had a misunderstanding, and Patiño took his revenge to Apolonio by revealing the secrets of the society to his sister, Honoria. The latter was reported to have cried. The madre portera, Sor Teresa, suggested that Teodoro Patiño tell all he knew to Father Mariano. Afternoon of August 19, Patiño told Father Mariano of what he knew about the secret society. The friar immediately hurried to the printing shop, Diario de Manila and searched the premises for the hidden proofs of the existence of the Katipunan with the accompaniment of the owner of the periodical. The lithographic stone used to print the Katipunan receipts was found and when it was shown to Patiño, he confirmed that it was true. At midnight, the locker of Policarpio Turla, whose signature appeared in the receipts, was forced open and the rules of the society and other pertinent documents were found. These proofs were turned over to the police and were now convinced to the existence of a vast underground society whose purpose is to overthrow Spanish sovereignty in the Philippines.[20]

Legal document

editThe introduction to the original Tagalog text of the Biak-na-Bato Constitution states:

Ang paghiwalay ng Filipinas sa kahariang España sa patatag ng isang bayang may sariling pamamahala’t kapangyarihan na pangangalang “Republika ng Filipinas” ay siyang layong inadhika niyaring Paghihimagsik na kasalukuyan, simula pa ng ika- 24 ng Agosto ng taong 1896… (English: The separation of the Philippines from the Spanish empire by the establishment of a self-governing nation called the "Republic of the Philippines" has been the aim of the current Revolution, starting on August 24, 1896.

The Spanish text also states:

la separación de Filipinas de la Monarquia Española, constituyéndose en Estado Independiente y soberano con Gobierno propio, con el nombre de República de Filipinas, es en su Guerra actual, iniciada en 24 de Agosto de 1896… (English: The separation of the Philippines from the Spanish Monarchy, constituting an independent state and with a proper sovereign government, named the Republic of the Philippines, was the end pursued by the revolution through the present hostilities, initiated on 24 August 1896…)

These lines indicate that in so far as the leaders of the revolution are concerned, revolution began on 24 August 1896.[citation needed] The document was written only one and a half years after the event and signed by over 50 Katipunan members, among them Emilio Aguinaldo , Artemio Ricarte and Valentin Diaz.

Emilio Aguinaldo’s memoirs, Mga Gunita ng Himagsikan (1964, English title:Memories of the Revolution), refer to two letters from Andres Bonifacio dated 22 and 24 August that pinpoint the date and place of the crucial Cry meeting when the decision to attack Manila was made.[8]

Tearing of cédulas

editNot all accounts relate the tearing of cédulas in the last days of August. Of the accounts that do, older ones identify the place where this occurred as Kangkong in Balintawak/Kalookan. Most also give the date of the cédula-tearing as August 26, in close proximity to the first encounter. One Katipunero, Guillermo Masangkay, claimed cédulas were torn more than once – on the 24th as well as the 26th.[4]

For his 1956 book The Revolt of the Masses Teodoro Agoncillo defined "the Cry" as the tearing of cedulas, departing from precedent which had then defined it as the first skirmish of the revolution. His version was based on the later testimonies of Pío Valenzuela and others who claimed the cry took place in Pugad Lawin instead of Balintawak. Valenzuela's version, through Agoncillo's influence, became the basis of the current stance of the Philippine government. In 1963, President Diosdado Macapagal ordered the official commemorations shifted to Pugad ng uwak, Quezon City on August 23.[5][4]

Formation of an insurgent government

editAn alternative definition of the Cry as the "birth of the Filipino nation state" involves the setting up of a national insurgent government through the Katipunan with Bonifacio as President in Banlat, Pasong Tamo on August 24, 1896 – after the tearing of cedulas but before the first skirmish. This was called the Haring Bayang Katagalugan (Sovereign Tagalog Nation).[3]

Why Balintawak?

editThe Cry of Rebellion in the Philippines happened in August 1896. There are lot of controversies puzzling the minds of the readers regarding the real place and date of this event.[21] Some accounts pointing directly to Balintawak are associated with 'The Cry’. Lt. Olegario Diaz of the Spanish Civil Guards wrote in 1896 that the event happened in Balintawak,[22] which corroborates the accounts of the historian Gregorio Zaide and Teodoro Kalaw.[citation needed] On the other hand, Teodoro Agoncillo based his account from that of Pio Valenzuela that emphasized Pugad Lawin as the place where the ‘cry’ happened.[citation needed]

Here are some reasons why Pugad Lawin is not considered as the place of the ‘cry’. (1) People of Balintawak initiated the revolution against the Spaniards that is why it is not appropriate to call it ‘Cry of Pugad Lawin’. (2) The place Pugad Lawin only existed in 1935 after the rebellion happened in 1896. Lastly, (3) The term ‘Pugad Lawin’ was only made up because of the hawk’s nest at the top of a tall tree at the backyard of Tandang Sora in Banlat, Gulod, Kaloocan where it is said to be one of the hiding places of the revolutionary group led by Andres Bonifacio.[23][failed verification]

Other cries

editIn 1895, Bonifacio, Masangkay, Emilio Jacinto and other Katipuneros spent Good Friday in the caves of Mt. Pamitinan in Montalban (now part of Rizal province). They wrote "long live Philippine independence" on the cave walls, which some Filipino historians consider the "first cry" (el primer grito).[4]

Commemoration

editThe Cry is commemorated as National Heroes Day, a public holiday in the Philippines.[24]

The first annual commemoration of the Cry occurred in Balintawak in 1908 after the American colonial government repealed the Sedition Law. A privately funded Monument to the Heroes of 1896 (a lone Katipunero popularly identified with Bonifacio) that had been inaugurated at Balintawak on September 3, 1911 was dismantled in 1968 to make way for a cloverleaf interchange. Through the efforts of the National Historical Commission and the University of the Philippines, the monument was re-inaugurated on November 29, 1968 in front of Vinzons Hall on the UP Dillman campus.[25] In 1984, the National Historical Institute of the Philippines installed a commemorative plaque in Pugad Lawin.[4]

See also

editFootnotes

edit- ^ Officially known as the Kataastaasang Kagalanggalangang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan; often abbreviated as KKK.

References

edit- ^ Sichrovsky, Harry. "An Austrian Life for the Philippines:The Cry of Balintawak". Retrieved August 29, 2009.

- ^ Ocampo, Ambeth R. (1995). Bonifacio's bolo. Anvil Pub. p. 8. ISBN 978-971-27-0418-5.

- ^ a b c d e Guerrero, Milagros; Encarnacion, Emmanuel; Villegas, Ramon (1996), "Balintawak: the Cry for a Nationwide Revolution", Sulyap Kultura, 1 (2), National Commission for Culture and the Arts: 13–22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Borromeo-Buehler, Soledad M. (1998), The Pugad ng Parrot: a contrived controversy : a textual analysis with appended documents, Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-278-8.

- ^ a b "Proclamation No. 149, s. 1963". Official Gazette of the Philippine Government. August 22, 1963.

- ^ a b De Viana, A.V. (2006). The I-stories: The Philippine Revolution and the Filipino-American War as Told by Its Eyewitnesses and Participants. University of Santo Tomas Publishing House. ISBN 978-971-506-391-3. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ a b Zaide, Gregorio (1990). "Cry of balintawak". Documentary Sources of Philippine History. 8: 307–309.

- ^ a b "In Focus: Balintawak: The Cry for a Nationwide Revolution". ncca.gov.ph. June 6, 2003. Archived from the original on June 25, 2022. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

na hindi sa Balintawak nangyari ang unang sigaw ng paghihimagsik na kinalalagian ngayon ng bantayog, kung di sa pook na kilala sa tawag na Pugad Lawin

- ^ Zaide, Gregorio (1990). "Cry of Pugad Lawin". Documentary Sources of Philippine History. 8: 301–302.

- ^ Batis: Sources in Philippines History, Jose Victor Torres

- ^ Duka, Cecilio D. (2008). Struggle for Freedom: A Textbook on Philippine History. Rex Book Store, Inc. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-971-23-5045-0.

- ^ "Come August, Remember Balintawak". Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

- ^ John lee Candelaria, Veronica Alporha. Readings in Philippine history.

- ^ Tamayao, Antonio. Readings in Philippine history.

- ^ Dr. Eusebo Koh Vol. 26 no. 04, John N. Schumacher Vol. 20 no. 04, Chris Antonette Piedad-Pugay

- ^ "Readings in the Philippine History: What Happened in the Cavite Mutin…". December 10, 2018.

- ^ "Cavite Mutiny". prezi.com.

- ^ "Cavite Mutiny | Summary, Importance, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ "CHAPTER Eight: JOSE P. RIZAL'S EXILE IN DAPITAN (1892-1896)". Jose Protasio Rizal Mercado y Alonzo Realonda.

- ^ History of the Filipino People 8th Edition by Teodoro A. Agoncillo

- ^ The cry of Balintawak : a contrived controversy : a textual analysis with appended documents. Centennial of the revolution. Ateneo de Manila University Press. 1998. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ Duka, Cecilio D. (2008). Struggle for Freedom' 2008 Ed. Rex Bookstore, Inc. p. 141. ISBN 978-971-23-5045-0.

- ^ "Bonifacio Papers". Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ "Monday holiday remembers historic "Cry of Balintawak"". Philippine Information Agency (Press release). August 28, 2009. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020.

- ^ Samonte, Severino (August 23, 2021). "Relocation of 'First Cry' monument from Balintawak to UP recalled". Philippine News Agency. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- "In Focus: Balintawak: The Cry for a Nationwide Revolution". ncca.gov.ph. Archived from the original on June 25, 2022. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

Further reading

edit- Borromeo, Soledad Masangkay (1998). The Cry of Balintawak: A Contrived Controversy : a Textual Analysis with Appended Documents. Ateneo University Press. ISBN 978-971-550-278-8.