Richard Karl Freiherr von Weizsäcker (German: [ˈʁɪçaʁt fɔn ˈvaɪtszɛkɐ] ; 15 April 1920 – 31 January 2015) was a German politician (CDU), who served as President of Germany from 1984 to 1994. Born into the aristocratic Weizsäcker family, who were part of the German nobility, he took his first public offices in the Protestant Church in Germany.

Richard Freiherr von Weizsäcker | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

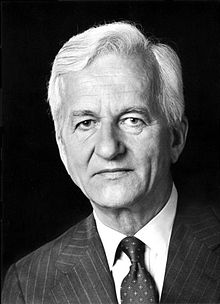

Weizsäcker in 1984 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President of Germany[a] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1 July 1984 – 30 June 1994 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellor | Helmut Kohl | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Karl Carstens | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Roman Herzog | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governing Mayor of West Berlin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 11 June 1981 – 9 February 1984 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mayor | Heinrich Lummer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Hans-Jochen Vogel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Eberhard Diepgen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Christian Democratic Union in West Berlin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 21 March 1981 – December 1983 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Peter Lorenz | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Eberhard Diepgen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice President of the Bundestag (on proposal of the CDU/CSU-group) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 21 June 1979 – 21 March 1981 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Richard Stücklen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Richard Stücklen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Heinrich Windelen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Richard Karl Freiherr von Weizsäcker 15 April 1920 New Palace, Stuttgart, Württemberg, Weimar Republic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 31 January 2015 (aged 94) Berlin, Federal Republic of Germany | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Christian Democratic Union (1954–2015) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Marianne von Kretschmann | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parent(s) | Ernst von Weizsäcker Marianne von Graevenitz | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Balliol College, Oxford University of Göttingen (Dr. jur.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A member of the CDU since 1954, Weizsäcker was elected as a member of parliament at the 1969 elections. He continued to hold a mandate as a member of the Bundestag until he became Governing Mayor of West Berlin, following the 1981 state elections. In 1984, Weizsäcker was elected as President of the Federal Republic of Germany and was re-elected in 1989 for a second term. As yet, he and Theodor Heuss are the only two Presidents of the Federal Republic of Germany who have served two complete five-year-terms. On 3 October 1990, during his second term as president, the reorganized five states of the German Democratic Republic and East Berlin joined the Federal Republic of Germany, which made Weizsäcker President of a reunified Germany.

Weizsäcker is considered the most popular of Germany's presidents,[1] held in high regard particularly for his impartiality.[2][3] His demeanor often saw him at odds with his party colleagues, particularly longtime Chancellor Helmut Kohl. He was famous for his speeches, especially one he delivered at the 40th anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe on 8 May 1985. Upon his death, his life and political work were widely praised, with The New York Times calling him "a guardian of his nation's moral conscience".[4]

Early life

editChildhood, school and family

editRichard von Weizsäcker was born on 15 April 1920 in the New Palace in Stuttgart,[5] the son of diplomat Ernst von Weizsäcker, a member of the Weizsäcker family, and his wife Marianne von Graevenitz, a daughter of Friedrich von Graevenitz (1861–1922), a General of the Infantry of the Kingdom of Württemberg.[6] Ernst von Weizsäcker was a career diplomat who served as State Secretary at the Foreign Office for Nazi Germany and as Nazi Germany’s ambassador to the Holy See[7].[8] The youngest of four children, Weizsäcker had two brothers, the physicist and philosopher Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker and Heinrich von Weizsäcker who fell as a soldier in Poland at the beginning of World War II. The sister Adelheid (1916–2004) married Botho-Ernst Graf zu Eulenburg-Wicken (1903–1944), a landowner in East Prussia. Richard's grandfather Karl von Weizsäcker had been Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Württemberg, and was ennobled in 1897 and raised to the hereditary title of Baron (Freiherr) in 1916.[9] His term in office ended in 1918, shortly before the monarchy was abolished in the German Revolution of 1918–1919. However, during the following years, he still occupied an apartment in the former royal palace where his grandson was born in an attic room.

Because his father was a career diplomat, Weizsäcker spent much of his childhood in Switzerland and Scandinavia. The family lived in Basel 1920–24, in Copenhagen 1924–26, and in Bern 1933–36, where Richard attended the Swiss Gymnasium Kirchenfeld. The family lived in Berlin, in an apartment in the Fasanenstraße in Wilmersdorf, between 1929 and 1933 and again from 1936 until the end of the Second World War.[10] Weizsäcker was able to miss the third class of his elementary school, and entered a secondary school at the young age of nine, the Bismarck-Gymnasium (now the Goethe-Gymnasium) in Wilmersdorf.[11] When he was 17 years old, Weizsäcker travelled to England to study philosophy and history at Balliol College, Oxford. In London, he witnessed the coronation of King George VI.[12] He spent the winter semester of 1937/38 at the University of Grenoble in France to improve his French.[13] He was mustered for the army there in 1938 and moved back to Germany the same year to start his Reichsarbeitsdienst.[14]

Second World War

editAfter the outbreak of the Second World War, Weizsäcker joined the Wehrmacht, ultimately rising to the rank of captain in the reserves. He joined his brother Heinrich's regiment, the Infantry Regiment 9 Potsdam. He crossed over the border to Poland with his regiment on the very first day of the war.[15] His brother Heinrich was killed about a hundred meters away from him on the second day. Weizsäcker watched over his brother's body through the night, until he was able to bury him the next morning.[16] His regiment, consisting in a large part of noble and conservative Prussians, played a significant part in the 20 July plot, with no fewer than nineteen of its officers involved in the conspiracy against Hitler.[17] Weizsäcker himself helped his friend Axel von dem Bussche in an attempt to kill Hitler at a uniform inspection in December 1943, providing Bussche with travel papers to Berlin. The attempt had to be called off when the uniforms were destroyed by an air raid. Upon meeting Bussche in June 1944, Weizsäcker was also informed of the imminent plans for 20 July and assured him of his support, but the plan ultimately failed.[18] Weizsäcker later described the last nine months of the war as "agony".[19] He was wounded in East Prussia in 1945 and was transported home to Stuttgart, to see out the end of the war on a family farm at Lake Constance.[20]

Education, marriage and early work life

editAt the end of the war Weizsäcker continued his study of history in Göttingen and went on to study law,[21] but he also attended lectures in physics and theology.[22] In 1947, when his father Ernst von Weizsäcker was a defendant in the Ministries Trial for his role in the deportation of Jews from occupied France, Richard von Weizsäcker served as his assistant defence counsel.[23][24] He took his first legal Staatsexamen in 1950, his second in 1953, and finally earned his doctorate (doctor juris) in 1955. In 1953 he married Marianne von Kretschmann. They had met when she was an 18-year-old schoolgirl and he was thirty. In 2010, Weizsäcker described the marriage as "the best and smartest decision of my life".[25] They had four children:[26] Robert Klaus von Weizsäcker, a professor of economics at the Technical University of Munich,[27] Andreas von Weizsäcker, an art professor at the Academy of Fine Arts Munich,[28] Beatrice von Weizsäcker, a lawyer and journalist,[29] and Fritz Eckhart von Weizsäcker, chief physician at the Schlosspark-Klinik in Berlin.[30][31] In the late 1970s, his son Andreas was a student at the Odenwaldschule. When reports about sexual abuse there surfaced in 2010, it was speculated in the media that Andreas might have been one of the victims, but this was denied by the family.[32] Andreas died of cancer in June 2008, aged 51.[28] Weizsäcker's son Fritz was murdered by a man armed with a knife on 19 November 2019, while holding a lecture at the Schlosspark-Klinik in Berlin, where he worked.[33][34]

Weizsäcker worked for Mannesmann between 1950 and 1958, as a scientific assistant until 1953, as a legal counsel from 1953, and as head of the department for economic policy from 1957.[35] From 1958 to 1962, he was head of the Waldthausen Bank, a bank owned by relatives of his wife. From 1962 to 1966, he served on the board of directors of Boehringer Ingelheim, a pharmaceutical company.[36] It was involved in production of the Agent Orange. This fact is speculated to be the motive behind the murder of his son in 2019, though the suspect has been sent to a secure hospital unit due to a "delusional general aversion" against the victim's family.[37][38]

German Evangelical Church Assembly

editBetween 1964 and 1970, Weizsäcker served as president of the German Evangelical Church Assembly. He was also a member of the Synod and the Council of the Protestant Church in Germany from 1967 to 1984.[39] During his early tenure as president, he wrote a newspaper article supporting a memorandum written by German evangelical intellectuals including Werner Heisenberg and his brother Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker who had spoken out in favour of accepting the Oder–Neisse line as the western border of Poland as an indispensable precondition for lasting peace in Europe. While this was met by negative reactions from politicians, especially in Weizsäcker's own party, he nevertheless led the Evangelical Church on a way to promoting reconciliation with Poland, leading to a memorandum by the Church in both West and East Germany. The paper was widely discussed and met with a significantly more positive response.[40]

Political career

editWeizsäcker joined the CDU in 1954. Some years later, Helmut Kohl offered him a safe seat for the 1965 elections, even going so far as to have Chancellor Konrad Adenauer write two letters urging him to run, but Weizsäcker declined, due to his work in the German Evangelical Church Assembly, wanting to avoid a conflict of interest.[41] However, he became a member of the Bundestag (Federal Diet) in the 1969 federal elections, serving until 1981.[42]

In 1974, Weizsäcker was the Presidential candidate of his party for the first time, but he lost to Walter Scheel of the FDP, who was supported by the ruling center-left coalition.[43] Ahead of the 1976 elections, CDU chairman Helmut Kohl included him in his shadow cabinet for the party's campaign to unseat incumbent Helmut Schmidt as chancellor. Between 1979 and 1981, Weizsäcker served as Vice President of the Bundestag.[5]

Governing Mayor of West Berlin (1981–84)

editWeizsäcker served as the Governing Mayor (Regierender Bürgermeister) of West Berlin from 1981 to 1984. During his years in office, he tried to keep alive the idea of Germany as a cultural nation, divided into two states. In his speeches and writings, he repeatedly urged his compatriots in the Federal Republic to look upon themselves as a nation firmly anchored in the Western alliance, but with special obligations and interests in the East.[43] Weizsäcker irritated the United States, France and Britain, the half-city's occupying powers, by breaking with protocol and visiting Erich Honecker, the East German Communist Party chief, in East Berlin.[44]

From 1981 to 1983, Weizsäcker headed a minority government in West Berlin, after the CDU had only won 48 percent of seats in the state assembly. His government was tolerated by the Free Democratic Party, who were in a coalition with the Social Democrats at the federal level at the time. After Helmut Kohl had won the federal election in 1983 and had formed a government with the Free Democrats, Weizsäcker did the same in West Berlin.[45]

President of the Federal Republic of Germany (1984–94)

editIn 1984, Weizsäcker was elected as President of West Germany by the German Federal Convention, succeeding Karl Carstens and drawing unusual support from both the governing center-right coalition and the opposition Social Democratic Party;[43] he defeated the Green party candidate, Luise Rinser.[46]

First term (1984–89)

editRichard von Weizsäcker took office as president on 1 July 1984. In his inaugural address, he appealed to his nation's special consciousness, saying: "Our situation, which differs from that of most other nations, is no reason to deny ourselves a national consciousness. To do so would be unhealthy for ourselves and eerie to our neighbors."[47] He dedicated his first years in office mainly to foreign policy, travelling widely with Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher and choosing former Foreign Office employees as his personal advisors.[48]

Speech on the 40th anniversary of the end of World War II

editWeizsäcker, who was known as a great speaker,[49] delivered his most famous speech in 1985, marking the 40th anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe on 8 May 1945.[50][51] This came at a difficult time in West German politics. The country was caught up in a debate about whether Holocaust denial should be criminalized. At the same time, chancellor Helmut Kohl had accepted an invitation to visit a congress of the Silesian association of expellees which was to take place under the slogan "Silesia is ours!" ("Schlesien ist unser!"). This seemed to contradict the official position of the federal diet and government so that Kohl needed to lobby for the intended slogan to be changed.[52][53]

It was originally planned that United States President Ronald Reagan should take part in the Second World War memorial event in the Bundestag, shifting the emphasis from remembering the past to highlighting West Germany in its partnership with the Western Bloc. On Weizsäcker's strong urging, the occasion was marked without Reagan, who visited West Germany several days earlier instead, surrounding the G7–summit in Bonn.[53] Reagan's visit nevertheless sparked controversy, especially in the United States. In an attempt to reproduce the gesture made by Kohl and French President François Mitterrand a year earlier at Verdun, where they held hands in a symbolic moment, the chancellor and Reagan were set to visit the military cemetery in Bitburg. This raised objections, since the cemetery included the last resting place for several members of the Waffen-SS.[52][54]

It was in this climate that Weizsäcker addressed parliament on 8 May 1985. Here, he articulated the historic responsibility of Germany and Germans for the crimes of Nazism. In contrast to the way the end of the war was still perceived by a majority of people in Germany at the time, he defined 8 May as a "day of liberation".[55] Weizsäcker pointed out the inseparable link between the Nazi takeover of Germany and the tragedies caused by the Second World War.[50] In a passage of striking boldness, he took issue with one of the most cherished defenses of older Germans. "When the unspeakable truth of the Holocaust became known at the end of the war," he said, "all too many of us claimed they had not known anything about it or even suspected anything."[55]

We must not regard the end of the war as the cause of flight, expulsion and deprivation of freedom. The cause goes back to the start of the tyranny that brought about war. We must not separate 8 May 1945 from 30 January 1933.[50]

Weizsäcker during his speech on 8 May 1985

Most notably, Weizsäcker spoke of the danger of forgetting and distorting the past. "There is no such thing as the guilt or innocence of an entire nation. Guilt is, like innocence, not collective but personal. There is discovered or concealed individual guilt. There is guilt which people acknowledge or deny. [...] All of us, whether guilty or not, whether young or old, must accept the past. We are all affected by the consequences and liable for it. [...] We Germans must look truth straight in the eye – without embellishment and without distortion. [...] There can be no reconciliation without remembrance."[55]

Weizsäcker declared that younger generations of Germans "cannot profess a guilt of their own for crimes they did not commit."[44] With his speech, Weizsäcker was also one of the first representatives of Germany to remember the homosexual victims of Nazism as a "victim group."[56] This was also the case with his recognition of the Sinti and Roma as another victim group, a fact that was highlighted by the long-time head of the Central Council of German Sinti and Roma, Romani Rose.[57]

Weizsäcker's speech was praised both nationally and internationally.[58] The New York Times called it a "sober message of hope to the uneasy generations of young West Germans".[55] The president of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, Werner Nachmann, thanked Weizsäcker for his strong words,[59] as did Karl Ibach, a former member of the German Resistance, who called his speech a "moment of glory (Sternstunde) of our republic".[60] Weizsäcker was however criticized for some of his remarks by members of his own party. Lorenz Niegel, a politician of the sister party CSU, who had not taken part in the ceremony, objected to the term "day of liberation", referring to it instead as a "day of deepest humiliation".[61] The Greens were also absent during the speech, choosing instead to visit Auschwitz.[61] A year later, the Green politician Petra Kelly called the speech "correct, but not more than self-evident", pointing to speeches president Gustav Heinemann had made during his presidency.[62] The harshest criticism came from the Federation of Expellees, whose president Herbert Czaja, while thanking the president for highlighting the expellees' fate,[63] criticized his remark that "conflicting legal claims must be subordinated under the imperative of reconciliation".[64]

The speech was later released on vinyl and sold around 60,000 copies. Two million printed copies of its text were distributed globally, translated into thirteen languages, with 40,000 being sold in Japan alone. This does not include copies of the speech printed in newspapers, such as The New York Times, which reproduced it in full.[58]

Role in the historians' dispute

editSpeaking to a congress of West German historians in Bamberg on 12 October 1988, Weizsäcker rejected the alleged attempts by some historians to compare the systematic murder of Jews in Nazi Germany to mass killings elsewhere – such as Stalin's purges – or to seek external explanations for it.[65] Thereby he declared an end to the Historikerstreit ('historians' dispute') that had sharply divided German scholars and journalists for two years, stating "Auschwitz remains unique. It was perpetrated by Germans in the name of Germany. This truth is immutable and will not be forgotten."[66]

In his remarks to the historians, Weizsäcker said their dispute had prompted accusations that they sought to raise a "multitude of comparisons and parallels" that would cause "the dark chapter of our own history to disappear, to be reduced to a mere episode."[66] Andreas Hillgruber, a historian at Cologne University, whose 1986 book in which he linked the collapse of the eastern front and the Holocaust was one of the subjects of the dispute, declared himself in full agreement with Weizsäcker, insisting that he had never tried to "relativize" the past.[66]

Second term (1989–94)

editUnification of Germany

In free self-determination we want to complete Germany's unity and freedom; for our task, we are aware of our responsibility before God and the people; in a united Europe, we want to serve the peace of the world.

Weizsäcker's words in front of the Reichstag on 3 October 1990, which were drowned in the noise of the celebrating crowd.[67]

Because of the high esteem in which he was held by Germany's political establishment and in the population,[68] Weizsäcker is so far the only candidate to have stood for elections for the office of President unopposed; he was elected in that way to a second term of office on 23 May 1989.[69]

Weizsäcker took office for his second presidential term on 1 July 1989, and in the course of it he oversaw the end of the Cold War and the Reunification of Germany. Thereupon, Weizsäcker became the first all-German Head of State since Karl Dönitz in May 1945. At midnight on 3 October 1990, during the official festivities held before the Reichstag building in Berlin to mark the moment of the reunification of Germany, President Weizsäcker delivered the only speech of the night, immediately after the raising of the flag, and before the playing of the National Anthem. His brief remarks, however, were almost inaudible, due to the sound of the bells marking midnight, and of the fireworks that were released to celebrate the moment of reunification.[70] In those remarks he praised the accomplishment of German unity in freedom and in peace. He gave a longer speech at the act of state at the Berliner Philharmonie later that day.[71]

President of a unified Germany

editIn 1990, Weizsäcker became the first head of state of the German Federal Republic to visit Poland. During his four-day visit, he reassured Poles that the newly unified German state would treat their western and northern borders, which included prewar German lands, as inviolable.[72]

In 1992, Weizsäcker gave the eulogy at the state funeral of former Chancellor Willy Brandt at the Reichstag, the first state funeral for a former chancellor to take place in Berlin since the death of Gustav Stresemann in 1929. The funeral was attended by an array of leading European political figures, including French President François Mitterrand, Spanish Prime Minister Felipe Gonzalez and former Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev.[73]

Weizsäcker stretched the traditionally ceremonial position of Germany's president to reach across political, national, and age boundaries to address a wide range of controversial issues. He is credited with being largely responsible for taking the lead on an asylum policy overhaul after the arson attack by neo-Nazis in Mölln, in which three Turkish citizens died in 1993.[74] He also earned recognition at home and abroad for attending memorial services for the victims of neo-Nazi attacks in Mölln and Solingen. The services were snubbed by Chancellor Helmut Kohl, who dismayed many Germans by saying it was not necessary for the government to send a representative.[75]

In March 1994, Weizsäcker attended the Frankfurt premiere of the film Schindler's List along with the Israeli ambassador, Avi Primor, and the head of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, Ignatz Bubis.[76]

During the debate over the change of the seat of the German government from Bonn to Berlin, the president spoke out in favor of Berlin. In a memorandum released in February 1991, he declared that he would not act as a mere "decoration of a so-called capital",[77] urging the diet to move more constitutional organs to Berlin.[78][79] To compensate for a delay in the transfer to Berlin of the government and the federal parliament, Weizsäcker declared in April 1993 that he would be performing an increased share of his duties in Berlin.[80] He decided not to wait for the renovation and conversion as the presidential seat of the Kronprinzenpalais (Crown Prince's Palace) at Berlin's Unter den Linden boulevard, and to use instead his existing official residence in West Berlin, the Bellevue Palace beyond Tiergarten park.[80]

Critique of party politics

editIn an interview book released in 1992, midway through his second term, Weizsäcker voiced a harsh critique of the leading political parties in Germany, claiming that they took a larger role in public life than was awarded to them by the constitution. He criticized the high number of career politicians (Berufspolitiker), who "in general are neither expert nor dilettante, but generalists with particular knowledge only in political battle".[81] The immediate reactions toward this interview were mixed. Prominent party politicians such as Rainer Barzel and Johannes Rau criticized the remarks, as did Minister of Labour Norbert Blüm, who asked the president to show more respect towards the work done by party members. Former chancellor Helmut Schmidt, on the other hand, conceded that Weizsäcker was "essentially right". While comments from politicians were mainly negative, a public poll conducted by the Wickert-Institut in June 1992 showed that 87.4 percent of the population agreed with the president.[82] Political commentators generally interpreted the remarks as a hidden attack on the incumbent chancellor Helmut Kohl, since Weizsäcker's relationship with his former patron had cooled over the years.[82] In a column for the German newspaper Der Spiegel, chief-editor Rudolf Augstein criticized the president for his attack, writing: "You cannot have it both ways: on the one hand giving a right and seminal political incentive, but on the other hand insulting the governing class and its chief".[83]

Travels

editOn his trip to Israel in October 1985, Weizsäcker was greeted on arrival by his Israeli counterpart, President Chaim Herzog. The president was given a full honor-guard welcome at Ben-Gurion Airport; among Cabinet ministers who lined up to shake his hand were right-wingers of the Herut party, the main faction of Foreign Minister Yitzhak Shamir's Likud party, who had previously refused to greet German leaders. Weizsäcker's visit was the first by a head of state, but not the first by a West German leader, as Chancellor Willy Brandt had paid a visit to Israel in June 1973.[84] During a four-day state visit to the United Kingdom in July 1986, Weizsäcker addressed a joint session of the Houses of Parliament, the first German to be accorded that honor.[85]

In 1987, he travelled to Moscow to meet Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in what was perceived as a difficult time in West German-Soviet relations, after chancellor Kohl had angered Moscow by comparing Gorbachev to Joseph Goebbels.[86][87] During a speech at the Kremlin, Weizsäcker said: "The Germans, who today live separated into East and West, have never stopped and will never stop to feel like one nation."[88] His speech was, however, censored in the official Communist Party newspaper Pravda. However, when German foreign minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher protested against this to his Soviet counterpart Eduard Shevardnadze, the speech was then printed unabridged in the lesser paper Izvestia. Weizsäcker also appealed to the Soviet authorities to agree to a pardon for the last inmate in the Spandau Prison, former Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess. This proved unsuccessful, and Hess committed suicide six weeks later.[89] The visit was nevertheless considered a success, as Gorbachev was quoted afterwards saying that "a new page of history was opened",[90] after the two had discussed matters of disarmament.[91] Also in 1987, Erich Honecker became the first East German leader to visit the Federal Republic. While state guests in Germany are usually welcomed by the President, Honecker was still not greeted officially by Weizsäcker, but by chancellor Kohl, since the Federal Republic did not consider the GDR a foreign state. Weizsäcker did however receive Honecker later at his seat of office, the Hammerschmidt Villa.[92]

Post-presidency

editAs an elder statesman, Weizsäcker long remained involved in politics and charitable affairs in Germany after his retirement as president. He chaired a commission established by the Social Democratic-Green government of the day for reforming the Bundeswehr.[93] Along with Henry Kissinger, in 1994 he supported Richard Holbrooke in creating the American Academy in Berlin.[94] He was also a member of the Board of Trustees of the Robert Bosch Stiftung.

Weizsäcker served as a member of the Advisory Council of Transparency International.[95] In a letter addressed to Nigeria's military ruler Sani Abacha in 1996, he called for the immediate release of General Olusegun Obasanjo, the former head of state of Nigeria, who had become the first military ruler in Africa to keep his promise to hand over power to an elected civilian government but was later sentenced to 15 years imprisonment.[96]

Weizsäcker also served on many international committees. He was chairman of the Independent Working Group on the future of the United Nations and was one of three "Wise Men" appointed by European Commission President Romano Prodi to consider the future of the European Union. From 2003 until his death, he was a member of the Advisory Commission on the return of cultural property seized as a result of Nazi persecution, especially Jewish property, led by the former head of the Federal Constitutional Court, Jutta Limbach. In November 2014, Weizsäcker retired as chairman of the Bergedorf Round Table, a discussion forum on foreign policy issues.[97]

Death and funeral

editWeizsäcker died in Berlin on 31 January 2015, aged 94. He was survived by his wife, Marianne, and three of their four children.[4] Upon his death, there was general praise for his life and political career. In its obituary, The New York Times called Weizsäcker "a guardian of his nation's moral conscience",[4] while The Guardian commented that Germany was "uniquely fortunate" in having had him as a leader.[98]

He was honored with a state funeral on 11 February 2015 at Berlin Cathedral. Eulogies were given by incumbent president Joachim Gauck, foreign minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier (SPD), finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble (CDU) and former vice president of the Bundestag Antje Vollmer (Green Party). Steinmeier praised Weizsäcker's role in foreign relations, where he had worked towards reconciliation with France and Poland and supported a dialogue with the communist regimes in the East, often against his own party.[99] The funeral was attended by many serving high-ranking politicians in Germany, including chancellor Angela Merkel. Also in attendance were former presidents Roman Herzog, Horst Köhler, and Christian Wulff, as well as former chancellors Helmut Schmidt and Gerhard Schröder. Princess Beatrix, former Queen of the Netherlands, was also present, as was former Polish president Lech Wałęsa.[100] After the ceremony, soldiers stood to attention as Weizsäcker's coffin was brought to its resting place at Waldfriedhof Dahlem.[99] In the subsequent days, many Berliners visited Weizsäcker's grave to pay tribute and lay down flowers.[101] On 15 April 2020, von Weizsäcker's 100th birthday, incumbent Governing Mayor of Berlin Michael Müller and Ralf Wieland, president of the Abgeordnetenhaus, Berlin's state parliament, laid down a wreath at his grave in honour of his services to the city of Berlin.[102]

Relationship with his party and Helmut Kohl

editWeizsäcker, who had joined the CDU in 1954, was known for often publicly voicing political views different from his own party line, both in and out of the presidential office. While he was himself sceptical of Willy Brandt's Ostpolitik, he urged his party not to block it entirely in the lower house, the Bundestag, since rejection would be met with dismay abroad. When the CDU gained a sweeping victory in the state elections in Baden-Württemberg in April 1972, his party decided to take the opportunity to dispose of chancellor Brandt with a vote of no confidence, replacing him with Rainer Barzel, and Weizsäcker was one of only three elect CDU politicians to speak out against the proposal.[103] He maintained an easy-going and open demeanor towards members of all other parties. In 1987, at a time when the CDU actively tried to label the Green Party as unconstitutional, the President had regular contact with high-ranking Green politicians such as Antje Vollmer, who was also active in the Protestant Church in Germany, and Joschka Fischer, who said that with his understanding of state "he [Weizsäcker] is closer to the Green Party than to Kohl, not NATO, but Auschwitz as reason of state (Staatsräson)."[104]

Helmut Kohl, who served as Chancellor of Germany from 1982 to 1998, was an early patron of Weizsäcker's, effectively helping him into parliament. However, their relationship took a first strain in 1971, when Weizsäcker supported Rainer Barzel over Kohl for the CDU-chairmanship. Subsequently, Kohl unsuccessfully tried to deny Weizsäcker the chance to become president in 1983.[105] After he had taken office, Weizsäcker criticized Kohl's government on numerous occasions, taking liberties not previously heard of from someone in a ceremonial role such as his. For instance, he urged the chancellor to recognize the Oder–Neisse line[106] and spoke out for a more patient approach to the journey towards German reunification.[105] Other examples include the aforementioned speech in 1985 and his critique of party politics in 1992. Following a critical interview Weizsäcker gave to Der Spiegel magazine in September 1997, Kohl reacted during a meeting of his parliamentary group by saying that Weizsäcker (whom he called "that gentleman")[77] was no longer "one of us".[107] This was followed by CDU spokesman Rolf Kiefer stating that the CDU had removed Weizsäcker from its membership database, since the former president had not paid his membership fees in a long time. Weizsäcker then took the matter to the party's arbitrating body and won. The tribunal ruled that he was allowed to let his membership rest indefinitely.[107] After his death, Spiegel editor Gerhard Spörl called Weizsäcker the "intellectual alternative medicine to Kohl".[108]

It was specifically Berlin's Turks from whom I won my view that the German citizenship law was in urgent need for reform. [...] The longer it lasted, the more the jus sanguinis lost its sense compared to a jus soli. Should it really be made difficult for children of foreigners in the third generation to become Germans, even though it would not be a return, but emigration for them to go to the country of their ancestors [...]?[109]

Weizsäcker on his years as Governing Mayor of West Berlin and his views on citizenship.

After his presidency came to an end, Weizsäcker remained vocal in daily politics, e.g. speaking for a more liberal immigration policy, calling the way his party handled it "simply ridiculous".[110] He also spoke out in favour of dual citizenship and a change of German citizenship law from jus sanguinis to jus soli, a view not generally shared by his party colleagues.[111] Towards the former East-German leading party, the PDS (today called Die Linke), Weizsäcker urged his party colleagues to enter into a serious political discussion. He went as far as speaking in favor of a coalition government between Social Democrats and the PDS in Berlin after the 2001 state election.[112]

Publications

editWeizsäcker's publications include Die deutsche Geschichte geht weiter (German History Continues), first published in 1983;[87] Von Deutschland aus (From Germany Abroad), a collection of speeches first published in 1985;[113] Von Deutschland nach Europa (From Germany to Europe, 1991)[114] and his memoirs Vier Zeiten (Four Times), published in German in 1997[115] and in English as From Weimar to the Wall: My Life in German Politics in 1999.[116] In a review in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Friedrich Karl Fromme wrote that the memoirs tell nothing new about the times he lived in, but "something about the person".[117] In 2009, he published a book on his recollections of German reunification, titled Der Weg zur Einheit (The Path to Unity). German newspaper Die Welt dismissed the book as "boring", accusing the account of being too balanced.[118]

Other activities and recognition

editWeizsäcker received many honors in his career, including honorary membership in the Order of Saint John;[119] an honorary doctorate from Johns Hopkins University in 1993; creation of the Richard von Weizsäcker Professorship at the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) of Johns Hopkins University and the Robert Bosch Foundation of Stuttgart in 2003; and more than eleven other honorary doctorates, ranging from the Weizmann Institute in Israel to Oxford, Cambridge, and Harvard universities, the Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Law (1995) at Uppsala University[120] and the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras,[121] the Leo Baeck Prize from the Central Council of Jews in Germany, and the Buber-Rosenzweig Medallion from the Society for Christian-Jewish Cooperation. After his death, deputy director of Poland's international broadcaster, Rafal Kiepuszewski, called Weizsäcker "the greatest German friend Poland has ever had".[122]

Both Chancellor Angela Merkel and President Joachim Gauck praised Weizsäcker, with the latter declaring upon the news of his death: "We are losing a great man and an outstanding head of state."[123] French president François Hollande highlighted Weizsäcker's "moral stature."[123]

|

Weizsäcker's many awards and honors include:

|

His post-presidency activities include:

|

Ancestry

edit| Ancestors of Richard von Weizsäcker | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

edit- ^ From 1 July 1984 to 2 October 1990, Richard von Weizsäcker was President of West Germany only. From 3 October 1990 until 30 June 1994, he was President of the reunified Germany. The term West Germany is only the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany (GDR) in October 1990.

References

edit- ^ Augstein, Franziska (15 April 2010). "Erster Bürger seines Staates" (in German). Süddeutsche Zeitung. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Gauck würdigt "großen Deutschen"" (in German). Deutschlandfunk. 11 February 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ Schäuble, Wolfgang (11 February 2015). "Er ist immer unser Präsident geblieben". Faz.net (in German). Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ a b c Saxon, Wolfgang (31 January 2015). "Richard von Weizsäcker, 94, Germany's First President After Reunification, Is Dead". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Richard von Weizsäcker (1984–1994)". bundespraesident.de. Bundespräsidialamt. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ Hofmann 2010, p. 23.

- ^ "Collections Search - United States Holocaust Memorial Museum". collections.ushmm.org. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ Hofmann 2010, p. 19.

- ^ Rudolph 2010, p. 24.

- ^ Rudolph 2010, p. 25.

- ^ Weizsäcker 1997, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Weizsäcker 1997, p. 71.

- ^ Hofmann 2010, p. 30.

- ^ Weizsäcker 1997, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Rudolph 2010, p. 39.

- ^ Rudolph 2010, p. 40.

- ^ Finker, Kurt (1993), "Das Potsdamer Infanterieregiment 9 und der konservativ militärische Widerstand", in Kroener, Bernhard R. (ed.), Potsdam. Staat, Armee, Regiment, Berlin

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Weizsäcker 1997, p. 90.

- ^ Weizsäcker 1997, p. 91.

- ^ Weizsäcker 1997, p. 95.

- ^ Rudolph 2010, p. 54.

- ^ Weizsäcker 1997, pp. 98–102.

- ^ Rudolph 2010, p. 61.

- ^ Hofmann 2010, p. 88.

- ^ "Richard von Weizsäcker: Seine Familie war bis zuletzt bei ihm" (in German). B.Z. Berlin. 1 February 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ "Marianne von Weizsäcker" (in German). Bundespräsidialamt. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ "Lehrstuhl für Volkswirtschaftslehre – Finanzwissenschaft und Industrieökonomik" (in German). Technical University of Munich. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ a b "Richard von Weizsäcker trauert um seinen Sohn". Die Welt (in German). 15 June 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ Kaiser, Carl-Christian (29 January 1993). "Unter Brüdern". Die Zeit (in German). Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ "Chefarzt: Prof. Dr. med. Fritz von Weizsäcker". schlosspark-klinik.de (in German). Archived from the original on 24 August 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ "Richard von Weizsäcker: Ein Zeuge des 20. Jahrhunderts" (in German). Bayrischer Rundfunk. 31 January 2015. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ "Odenwaldschule: Familie Weizsäcker bricht Schweigen". Spiegel Online (in German). 27 March 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ "Was wir über den tödlichen Angriff auf Fritz von Weizsäcker wissen". Der Spiegel (in German). 20 November 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ "Son of former German President Richard von Weizsäcker stabbed to death". BBC News. 20 November 2019.

- ^ Rudolph 2010, p. 83.

- ^ Rudolph 2010, p. 91.

- ^ "German president's son Fritz von Weizsäcker stabbed to death in lecture in Berlin". The Times (in German). 21 November 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ "What we know about the killing of former German president's son". Deutsche Welle. 21 November 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Rudolph 2010, p. 98.

- ^ Weizsäcker 1997, pp. 179–185.

- ^ Rudolph 2010, p. 116.

- ^ Rudolph 2010, p. 119.

- ^ a b c Markham, James M. (24 May 1984). "A Patrician President in Bonn; Richard von Weizsacker (Published 1984)". The New York Times.

- ^ a b James M. Markham (23 June 1994), Facing Up To Germany's Past The New York Times Magazine.

- ^ Thomas, Sven (2005). Die informelle Koalition. Richard von Weizsäcker und die Berliner CDU-Regierung (1981–1983). Wiesbaden: Deutscher Universitäts-Verlag. ISBN 3-8244-4614-6.

- ^ "Die Bundesversammlungen 1949 bis 2010" (PDF) (in German). Deutscher Bundestag. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ Richard von Weizsäcker. Reden und Interviews (vol. 1), 1. Juli 1984 – 30. Juni 1985. Bonn: Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung. 1986. p. 16.

- ^ Weizsäcker 1997, pp. 308–316.

- ^ Andresen, Dirk J. (31 January 2015). "Richard von Weizsäcker: Der Präsident, den die Deutschen liebten" (in German). Berliner Kurier. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ a b c Richard von Weizsäcker. "Speech in the Bundestag on 8 May 1985 during the Ceremony Commemorating the 40th Anniversary of the End of War in Europe and of National-Socialist Tyranny" (PDF). Baden-Württemberg: Landesmedienzentrum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ Saxon, Wolfgang (31 January 2015). "Richard von Weizsäcker, 94, Germany's First President After Reunification, Is Dead". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ a b Gill 1986, p. 7.

- ^ a b Weizsäcker 1997, p. 317.

- ^ Weinraub, Bernard (6 May 1985). "Reagan Joins Kohl in Brief Memorial at Bitburg Graves". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d James M. Markham (9 May 1985), 'All of Us Must Accept the Past,' The German President Tells M.P.'s The New York Times.

- ^ "Denkmal für die im Nationalsozialismus verfolgten Homosexuellen". gedenkort.de. Memorial site for the persecuted homosexual victims of National Socialism. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ Gill 1986, p. 27.

- ^ a b Gill 1986, p. 8.

- ^ Gill 1986, p. 13.

- ^ Gill 1986, p. 37.

- ^ a b Leinemann, Jürgen (13 May 1985). "Möglichkeiten, das Gewissen abzulenken". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ Gill 1986, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Gill 1986, p. 91.

- ^ Gill 1986, p. 94.

- ^ Richard von Weizsäcker. Reden und Interviews (vol. 5), 1. Juli 1988 – 30. Juni 1989. Bonn: Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung. 1989. pp. 69–79.

- ^ a b c Serge Schmemann (22 October 1988), Bonn Journal; Facing the Mirror of German History The New York Times.

- ^ Richard von Weizsäcker. Reden und Interviews (vol. 7), 1. Juli 1990 – 30. Juni 1991. Bonn: Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung. 1992. p. 66. Translated by User:Zwerg Nase

- ^ Studemann, Frederick (31 January 2015). "Richard von Weizsäcker, German president 1920–2015". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "Die Bundesversammlungen 1949 bis 2010" (PDF) (in German). Deutscher Bundestag. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ Rudolph 2010, p. 245.

- ^ "Ansprache von Bundespräsident Richard von Weizsäcker beim Staatsakt zum "Tag der deutschen Einheit"". bundespraesident.de. Bundespräsidialamt. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ Borders Will Stay, Bonn's President Says in Poland Los Angeles Times, 3 May 1990.

- ^ Tyler Marshall (18 October 1992), Germans Lay Beloved Statesman Brandt to Rest Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Jochen Thies (14 January 1993), A New German Seriousness on the Asylum Problem International Herald Tribune.

- ^ Mary Williams Walsh (23 May 1994), German Electoral College to Pick New President Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Germans Applaud "Schindler's List" International Herald Tribune, 2 March 1994.

- ^ a b Translated by User:Zwerg Nase

- ^ Rudolph 2010, p. 261.

- ^ Richard von Weizsäcker. Reden und Interviews (vol. 7), 1. Juli 1990 – 30. Juni 1991. Bonn: Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung. 1992. pp. 391–397.

- ^ a b Michael Farr (21 April 1993), Economic Slide Rekindles Debate on Capitals International Herald Tribune.

- ^ Rudolph 2010, p. 256.

- ^ a b Rudolph 2010, p. 257.

- ^ Augstein, Rudolf (29 June 1992). "Weizsäcker und sein Traditionsbruch". Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ Weizsaecker Urges Openness to Truth of the Past : W. German President Makes Rare Israel Visit Los Angeles Times, 9 October 1985.

- ^ Bonn Official in Britain Los Angeles Times, 2 July 1986.

- ^ Grothe, Solveig (22 November 2010). "Seit Goebbels der schlimmste Hetzer im Land!". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Eine Kooperation auf neuem Niveau". Der Spiegel (in German). Vol. 1987, no. 28. 6 July 1987. pp. 19–21. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ^ Weizsäcker 1997, p. 343. Translated by User:Zwerg Nase.

- ^ Weizsäcker 1997, pp. 343–344.

- ^ Weizsäcker 1997, p. 346.

- ^ "Violations Von Weizsaecker Starts State Visit to Moscow : End Bloc Thinking, Bonn President Says". Los Angeles Times. Reuters. 7 July 1987. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ Weizsäcker 1997, pp. 349–350.

- ^ Cohen, Roger (24 May 2000). "Germans Plan To Trim Army And Rely Less On the Draft". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Means Lohmann, Sarah (25 December 2003). "In Berlin, a Showcase of American Talent and Thought Marks an Anniversary". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Advisory Council Archived 2 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine Transparency International.

- ^ Kinkel, Weizsäcker call for release of Nigeria's Obasanjo – An international campaign led by TI is to increase the pressure on Nigeria's rulers Archived 5 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine Transparency International, press release of 29 September 1996.

- ^ Abschiedsfeier für Alt-Bundespräsident von Weizsäcker Hamburger Abendblatt, 7 November 2014.

- ^ Vat, Dan van der (2 February 2015). "Richard von Weizsäcker obituary". guardian.co.uk. The Guardian. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ a b Conrad, Naomi. "Berlin pays last respects to former president". dw.de. Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ "Die Gäste der Trauerfeier – Abschied von Richard von Weizsäcker". handelsblatt.com (in German). Handelsblatt. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ Ohmann, Oliver (12 February 2015). "Berliner pilgern zum Grab von Richard von Weizsäcker". bild.de (in German). Bild. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ "Zum 100. Geburtstag: Müller ehrt Richard von Weizsäcker". Süddeutsche Zeitung (in German). Deutsche Presse-Agentur. 14 April 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ Rudolph 2010, p. 131.

- ^ "Näher den Grünen als Kohl". Der Spiegel (in German). Vol. 1987, no. 28. 6 July 1987. pp. 22–23. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ^ a b Rudolph 2010, p. 258.

- ^ Rudolph 2010, p. 259.

- ^ a b Schmidt-Klingenberg, Michael (22 September 1997). "Die Zierde der Partei". Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ Spörl, Gerhard (31 January 2015). "Erinnerungen an Richard von Weizsäcker: Er hat uns befreit". Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ Weizsäcker 1997, p. 288. Translated by User:Zwerg Nase.

- ^ Rudolph 2010, p. 269.

- ^ Weizsäcker 1997, p. 288.

- ^ Rudolph 2010, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Von Deutschland aus / Richard von Weizsäcker. Corso bei Siedler (in German). Deutsche Nationalbibliothek. 1985. ISBN 9783886801732. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ Von Deutschland nach Europa : die bewegende Kraft der Geschichte / Richard von Weizsäcker (in German). Deutsche Nationalbibliothek. 1991. ISBN 9783886803781. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ Vier Zeiten : Erinnerungen / Richard von Weizsäcker (in German). Deutsche Nationalbibliothek. 1997. ISBN 9783886805563. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ From Weimar to the Wall : my life in German politics / Richard von Weizsäcker. Transl. from the German by Ruth Hein (in German). Deutsche Nationalbibliothek. 1999. ISBN 9780767903011. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ Fromme, Friedrich Karl (29 May 1998). "Ein Mann der indirekten Sprache". Faz.net (in German). Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ Gauland, Alexander (16 September 2009). "Memoiren – Richard von Weizsäcker eckt nicht an". Die Welt (in German). Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ Verzeichnis der Mitglieder der Balley Brandenburg des Ritterlichen Ordens St. Johannis vom Spital zu Jerusalem; Berlin: Johanniterorden, 2011; page 18.

- ^ "Honorary doctorates - Uppsala University, Sweden". 9 June 2023.

- ^ "Landmarks – 1991". Indian Institute of Technology, Madras. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ Borrud, Gabriel. "The greatest German friend Poland has ever had". dw.de. Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ a b Reuters. "Merkel, Gauck laud Richard von Weizsäcker". dw.de. Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

{{cite web}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ "Royal Decree 389/1986". boe.es (in Spanish). Spanish Official Journal. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ "Senarai Penuh Penerima Darjah Kebesaran, Bintang dan Pingat Persekutuan Tahun 1987" (PDF). istiadat.gov.my (in Malay). Ceremonial and International Conference Secretariat, Prime Minister's Department of Malaysia. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ "Muere Richard von Weizsäcker, primer presidente de la Alemania reunificada". abc.es (in Spanish). 31 January 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Inkomend staatsbezoek" (in Dutch). Het Koninklijk Huis. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Atatürk Uluslararası Barış Ödülü". 3 July 2015.

- ^ Icelandic Presidency Website (Icelandic), Order of the Falcon, Weizsäcker, Richard von[permanent dead link], 4 July 1988, Grand Cross with Collar

- ^ "Hedersdoktor vid fakulteten avliden" (in Swedish). Uppsala Universitet. 31 January 2015. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Harnack Medal". mpg.de. Max-Planck-Gesellschaft. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Richard Freiherr von Weizsäcker". parlament-berlin.de. Abgeordnetenhaus Berlin. Archived from the original on 25 November 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ "Literaturpreis Gewinner". literaturpreisgewinner.de (in German). Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Ordensträger auf Empfang". Der Tagesspiegel Online (in German). Tagesspiegel. 28 June 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Past Laureates". unhcr.org. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Order Zaslugiprezydent.pl Archived 9 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Richard von Weizsäcker". gdansk.pl (in Polish). 11 July 2008. Archived from the original on 10 July 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Dr. Richard von Weizsäcker übernimmt Mercatorprofessur" (in German). Universität Duisburg-Essen. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "List". President of the Czech Republic. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Richard von Weizsäcker Receives 2009 Henry A. Kissinger Prize". The American Academy in Berlin. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Verleihung des "Preises für Verständigung und Toleranz" am 17. November 2012" (in German). Jüdisches Museum Berlin. 6 November 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Jüdisches Museum Berlin ehrt Richard von Weizsäcker" (in German). Jüdische Allgemeine. 6 November 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Zum Tode von Richard von Weizsäcker, Altbundespräsident und ehemaliger Schirmherr von Aktion Deutschland Hilft" (in German). Aktion Deutschland Hilft. 31 January 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Danke, Richard von Weizsäcker!" (in German). Körber-Stiftung. 2 February 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Club of Budapest". Club of Budapest. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Honorary Members". Club of Rome. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Kuratorium" (in German). Freya von Moltke Stiftung. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Richard von Weizsäcker Kuratoriumsmitglied des Hannah Arendt-Zentrums" (in German). Universität Oldenburg. 13 December 2002. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Keller, Hans-Christoph (31 January 2015). "Humboldt-Universität trauert um Richard von Weizsäcker" (in German). Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Retrieved 3 May 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Gesine Schwan zur Präsidentin der HUMBOLDT-VIADRINA School of Governance gewählt" (PDF) (in German). Gesine Schwan. 15 June 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "International Commission on the Balkans". Centre for Liberal Studies, Sofia. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Human Rights Award > Jury > 1995–2000". nuernberg.de. Human Rights Office, City of Nuremberg. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "The Boards & Advisory Council Philharmonic Orchestra of Europe e.V." Philharmonic Orchestra of Europe. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Board of Directors". Political Science Quarterly. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Kuratorium" (in German). Theodor Heuss Stiftung. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Beirat" (in German). Viktor-von-Weizsäcker-Gesellschaft. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

Bibliography

editEditions

edit- Richard von Weizsäcker. Reden und Interviews (vol. 1), 1. Juli 1984 – 30. Juni 1985. Bonn: Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung. 1986.

- Richard von Weizsäcker. Reden und Interviews (vol. 5), 1. Juli 1988 – 30. Juni 1989. Bonn: Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung. 1989.

- Richard von Weizsäcker. Reden und Interviews (vol. 7), 1. Juli 1990 – 30. Juni 1991. Bonn: Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung. 1992.

Monographs and miscellanies

edit- Gill, Ulrich, ed. (1986). Eine Rede und ihre Wirkung. Die Rede des Bundespräsidenten Richard von Weizsäcker vom 8. Mai 1985 anläßlich des 40. Jahrestages der Beendigung des Zweiten Weltkrieges (in German). Berlin: Verlag Rainer Röll. ISBN 3-9801344-0-7.

- Hofmann, Gunter (2010). Richard von Weizsäcker. Ein deutsches Leben (in German). Munich: C.H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-59809-8.

- Rudolph, Hermann (2010). Richard von Weizsäcker. Eine Biographie (in German). Berlin: Rowohlt. ISBN 978-3-87134-667-5.

- Weizsäcker, Richard von (1997). Vier Zeiten. Erinnerungen (in German). Berlin: Siedler Verlag. ISBN 3-88680-556-5.

External links

edit- Correspondence between President Weizsacker and the Israeli President Chaim Herzog during the First Gulf War, published by the blog of Israel State Archives

- Richard von Weizsäcker on the official website of the President's Office