Rodney is a ghost town in Jefferson County, Mississippi, United States.[1] Most of the buildings are gone and the remaining structures are in various states of disrepair. The town regularly floods and buildings have extensive flood damage. The Rodney History And Preservation Society is restoring Rodney Presbyterian Church, whose damaged facade from the American Civil War that includes a replica cannonball embedded above its balcony windows, has been maintained as part of the historical preservation. The Rodney Center Historic District is on the National Register of Historic Places.[2]

Rodney, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

Former First Presbyterian Church | |

| Nickname(s): "Petite Gulf", "Little Gulf"[1] | |

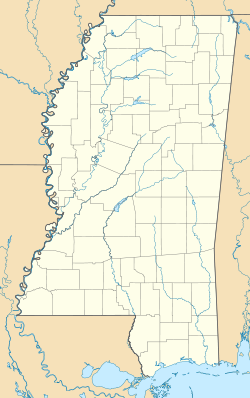

| Coordinates: 31°51′40.6″N 91°11′59.4″W / 31.861278°N 91.199833°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Jefferson |

| Founded | 1828 |

| Elevation | 82 ft (25 m) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| GNIS feature ID | 676809[1] |

The town is approximately 32 miles (51 km) northeast of Natchez and is currently about two miles (3.2 km) inland from the Mississippi River. Wetlands between the town and the river include a lake that roughly follows the river's former course. Atop the loess bluffs behind Rodney are its cemetery and Confederate earthworks from the Civil War.

In the early 19th century, Rodney was a cultural center of the region. In 1817, it was three votes away from becoming the capital of Mississippi.[3] Rush Nutt, a resident of Rodney, developed an important hybrid strain of cotton called Petit Gulf cotton and innovations to the cotton gin. In 1828, Rodney was incorporated and became the primary port for the surrounding area, with a population in the thousands. By 1860, the town was home to businesses, newspapers, and Oakland College. During the Civil War, Confederate States Army cavalry captured the crew of a Union Army ship who were attending a service in Rodney Presbyterian Church, resulting in the shelling of the town. After the war, the Mississippi River changed course, the railroad bypassed the area, and nearly all of buildings burned down. The population declined, and the town was disincorporated in 1930.[4] By 2010, only "a hand full of people" were living in Rodney.[5]

History

editRodney's landing site was a key waypoint on Native American routes around the Mississippi Delta region.[8] Native American artifacts have been unearthed between the town site and Natchez Trace overland route.[8] The Natchez people likely used the area as a portage between the Mississippi River and White Apple Village.[8]

French forces claimed the area around Rodney in January 1763 as Petit Gulf in contrast to Grand Gulf, upriver.[9] The name Petit Gulf referred to an inlet or narrow bend in the river, downstream from Bayou Pierre.[10] After the French and Indian War, the region was ceded to Great Britain.[11] The earliest-known land grant was to a Mr. Campbell in 1772.[12] Spain took control of the region in 1781, and gave many land grants in West Florida to Anglo immigrants.[13] American settlers, including the Nutt and Calvit families, moved into the area that would become Rodney.[14] Spain lost control of the area in 1798,[15][16] and on April 2, 1799, the Mississippi Territory was organized as a part of the United States.[17] Three years later, Delaware magistrate Thomas Rodney was sent to Jefferson County as a Territorial Judge.[18][19]

In 1807, Secretary of the Mississippi Territory Cowles Mead assembled a militia to capture Aaron Burr at Coles Creek, just south of Rodney.[20] Burr was held at Thomas Calvit's home while under investigation for treason.[21] Thomas Rodney presided over the Aaron Burr conspiracy trial and became Chief Justice of the Mississippi Territory.[22][23] The town was renamed after Rodney in 1814.[24] In the early 19th century, Rodney was more significant to the region than Vicksburg or Natchez.[9] In 1817, the Mississippi Territory was being admitted as a state, and Rodney was a candidate to become the state's capital but failed by three votes.[25]

Growth

editRodney, which was right on the water with the Mississippi River running parallel to its major streets, emerged as a thriving river port.[26][27] It was the primary shipping location for a broad swath of Mississippi, especially for cotton.[28] According to historian Keri Watson, enslaved dockworkers loaded "millions of pounds of cotton" onto steamboats bound for New Orleans.[24] Due to a shortage of legal tender, cotton receipts became a de facto currency.[29] During this period, many of the coins that were available were Spanish picayunes and bits.[12] According to a former Rodney storekeeper: "The northwest or Rodney district [of Jefferson County] was the home of McGill, Hubbard, Hopkins, Mackey, Turnbull, Rabb, Bradshaw, Sisson" as well as three American Revolutionary War veterans, Porter, Johnson and Caleb Potter, veterans of the Battle of Monmouth who were reintroduced to the Marquis de Lafayette on his 1824–25 tour of the United States.[30]

Rodney became a cultural center and incorporated in 1828.[9] Rodney resident Rush Nutt demonstrated effective methods of powering cotton gins with steam engines in 1830.[31] The importation of different types of cotton seeds resulted in the breeding of a disease-resistant and easy-to-harvest hybrid that became known as Petit Gulf cotton.[31] The seed business in Rodney served customers as far away as the North Carolina Piedmont.[32] The development of Petit Gulf cotton and the Indian Removal Act of 1830 spurred a westward land rush.[24] Many early settlers of Texas crossed through Rodney; their wagons were poled across the water on flatboat ferries to St. Joseph, Louisiana.[25] From 1820 to 1830, Rodney was the primary Mississippi River crossing for Americans migrating to the Southwest.[12]

Several historical structures were built during this time, including Rodney Presbyterian Church, U.S. president Zachary Taylor's plantation, and portions of Alcorn University, which was originally a Presbyterian college.[33][23] The initial building that was used for church services in Rodney doubled as a tavern, serving alcohol outside of Sundays.[34] In 1829, the first steps were taken to erect the red-brick Presbyterian church.[34] One year later, the Presbyterian Oakland College was chartered[35] and was built on 250 acres (100 ha) near the town.[36] In its first few years, the college operated from six cottages north of Rodney.[27] Construction began on the college's main building, the Greek-revival Oakland Memorial Chapel in 1838.[37] Zachary Taylor's Cypress Grove Plantation, Nutt's Laurel Hill, and other plantation homes were built around Rodney during this period.[24] Before the American Civil War, the town had two major newspapers; The Southern Telegraph and Rodney Gazette.[38][39] In 1836, the tagline of The Southern Telegraph was: "He that will not reason, is a bigot; he that cannot, is a fool; and he that dare not, is a slave".[40]

By the 1840s, growth was slowing; a Mississippi guidebook stated: "Its progress, some years ago, was very rapid, and much improvement was made, but it has been reputed to be very unhealthy, and, of late years, it has improved but very little". At that time, the town had several stores and "commission houses", a grist mill, a saw mill, and a church.[41]

Civil War

editDuring the Civil War, a group of Union Army soldiers were captured at Rodney Presbyterian Church.[42] Part of the Union's strategy during the Civil War was the plan to advance down the Mississippi River, dividing the Confederacy in half.[43] The Union's ship USS Rattler, a side-wheel steamboat, was retrofitted into a lightly armored warship.[44] After the Union captured the fortress city of Vicksburg, it took control of river traffic on the Mississippi. Rattler was one of many ships tasked with maintaining this control by preventing Confederate crossings. In September 1863, Rattler was anchored in the river near Rodney's landing.[45] Much of the town, including the surviving red-brick church, was visible from the water.[3]

When Reverend Baker from the Red Lick Presbyterian Church traveled to Rodney via steamboat, he invited Rattler's crew to go ashore and attend services in what was still Confederate territory.[45] On Sunday, September 13, 1863, seventeen men departed from Rattler to attend the 11 a.m. service.[45] Only a single crew member took a firearm to the service.[45] Confederate cavalry surrounded the building when the music was loud enough to cover their approach.[45][12] The troops entered the building and quickly captured the Northern soldiers with some assistance from members of the congregation.[45]

When reports reached the ship, Rattler began to fire upon the town; a cannonball lodged into the church above the balcony window. The shelling ceased when Confederate soldiers threatened to execute their Union prisoners.[3] Lt. Commander James A. Greer aboard USS Benton anchored upstream near Natchez and admonished Rattler's captain for acting as a civilian during a time of war. He issued orders to arrest any officer found "leaving his vessel to go on shore under any circumstances".[45]

Decline

editIn 1860, Rodney was home to banks, newspapers, schools, a lecture hall, Mississippi's first opera house, a hotel, and over 35 stores.[46][47] At its peak, thousands of people resided in the town.[3]

During the Civil War, the Mississippi River began to change course.[45] A sand bar developed upstream and pushed the river west,[2] and Rodney's former shipping channel became a swamp.[45] After the river changed course, Rodney gradually went from a major port to a ghost town.[9] The Rodney Landing was relocated several miles away from the town itself.[48] Many male residents who left the town during the war never returned, and many businesses permanently closed.[12] In 1869, a fire burned most of the town's buildings, but the Presbyterian church survived.[45] In 1880, German and Irish immigrants arrived and opened new businesses.[49] The town endured outbreaks of yellow fever.[24] The railroad bypassed the town, running through Fayette, Jefferson County's seat of government, and Rodney's landing was abandoned.[45] There are no records of any boats using the landing after 1900.[50]

Some residents remained in the vicinity, including an African-American man named Bob Smith, who had been marshal of Rodney "during Reconstruction days". According to histories published in the 1930s, Smith ran a "crude dining room" renowned for its delicious "fried chicken, hot cakes, fish, figs, etc. in season"[10] and "great stacks of savory froglegs."[51]

In 1930, Governor Theodore G. Bilbo disincorporated Rodney.[9] By 1938, Mississippi: A Guide to the Magnolia State described Rodney as "a ghost river town" that had died when the railroad passed it by.[9]

Novelist Eudora Welty found the town in ruins[9] and used Rodney as a setting in her works, including the novella The Robber Bridegroom.[24] Welty wrote: "The river had gone, three miles away, beyond sight and smell, beyond the dense trees. It came back only in flood."[24] Photographer Marion Post Wolcott documented Rodney for the Farm Security Administration circa 1940 and described it as a "fantastic deserted town".[52][53]

Extant structures

editA ruined cemetery, several stores, two churches, and few houses remain, in various states of disrepair. The red-brick Rodney Presbyterian Church, which was built in 1832,[3] is a federal-style church and the oldest remaining building in Rodney.[3][54] The Presbyterian church has fanlights above the doors similar to federal-style homes in Mississippi, like Rosalie Mansion.[54] The church's interior was lit with oil lamps and heated with a pair of stoves. A slave gallery in the rear can be accessed by a side door leading into a narrow, winding staircase.[51] It was built on on ground high enough to escape the town's regular flooding and has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1972.[55] The Rodney History and Preservation Society purchased the church to conduct repairs.[55] When the church was being restored, the hole created by Union cannonfire during the Civil War was retained and a replica cannonball was placed in the exterior wall.[45] Atop the hill adjacent to the church is a cemetery with graves dating back over a century.[56] It contains the graves of early settlers from across the river in Louisiana who took their dead to be buried on high ground above the floodplain.[12]

Mount Zion Baptist Church, which was built in 1851,[55] uses a combination of architectural styles.[2] The pointed arches are Greek Revival, the pedimented gable is Gothic Revival, and the domed cupola is federal style.[54] Mount Zion Baptist originally had a white congregation and became a predominantly African American church after white residents began to abandon the town, and is now completely abandoned.[3] Changes in the course of the Mississippi River have resulted in repeated flooding.[55] The structure shows signs of flood damage, including water lines and rotted floors.[55] A road sign pointing towards the church becomes visible in autumn when the leaves fall away from the vines overgrowing the signpost.[55] Surviving members of the church formed the Greater Mount Zion Church several miles away and outside the flood zone.[3]

Alston's Grocery, which was built circa 1840, is south of the Presbyterian Church at what was once the intersection of Commerce Street and Rodney Road.[55] The Sacred Heart Catholic Church was built in Rodney circa 1868, and the entire building was relocated to Grand Gulf Military State Park in 1983.[57][3] The gable-front Masonic lodge was built circa 1890.[55] Only a small number of people still live in the area and most of the remaining buildings are abandoned.[3]

Geography

editRodney is located near the southern end of the Natchez Trace, a forest trail that stretches for hundreds of miles across North America. The Trace was started by animal migration along a geologic ridge line.[58][59] The town is approximately 32 miles (51 km) northeast of Natchez, south of Bayou Pierre, and about 2 miles (3.2 km) inland from the east bank of the Mississippi River.[9][1][60] The town site is situated on loess bluffs that are within the Mississippi River watershed and were once adjacent to the river.[2] Wetlands, including a lake that roughly follows the river's old course, are immediately west of the town.[61] The town site is at a relatively low elevation and is prone to seasonal flooding. When the river ran past Rodney, its position on the lower bluffs above steep river banks created an ideal position for a river landing. Civil War–era earthworks are still present atop the bluffs above the town.[2]

Notable people

edit- James Cessor, member of the Mississippi House of Representatives from 1871 to 1877[62]

- Thomas Hinds Duggan, former member of the Texas Senate[63]

- Bill Foster, member of the Baseball Hall of Fame[64]

- Charles Pasquale Greco, Bishop of Alexandria in Louisiana from 1946 to 1973 and Supreme Chaplain of the Knights of Columbus from 1961 to 1987[65]

- Reuben C. Weddington, former member of the Arkansas House of Representatives[66]

- Zachary Taylor, the 12th president of the United States, built his Buena Vista plantation just south of Rodney.[24]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Rodney. Retrieved March 4, 2024. Archived from the original.

- ^ a b c d e "Rodney Center Historic District". National Park Service. Archived from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ghost Town on the Mississippi. The Steeple. PBS. January 11, 2013. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ Logan, Marie T. (1980). Mississippi–Louisiana Border Country (Revised 2nd ed.). Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Claitor's. LCCN 70-137737.

- ^ Grayson, Walt (August 26, 2010). "Rodney Presbyterian Church". WLBT3. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016.

- ^ D'Addario (December 19, 2019). "Review: Landscape art at NOMA entwines history, geography to show Louisiana as a world apart". NOLA. Retrieved June 29, 2024.

- ^ Carter, Kate (October 24, 2016). "Robert Brammer". 64 Parishes. Retrieved June 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c Logan 1980, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h McHaney, Pearl Amelia (Spring 2015). "Eudora Welty's Mississippi River: A View from the Shore". The Southern Quarterly. 52 (3): 66–68. ISSN 2377-2050.

- ^ a b Powell, Susie V., ed. (1938). Jefferson County (PDF). Source Material for Mississippi History, Volume XXXII, Part I. WPA Statewide Historical Research Project. pp. 12–14, 308–309 – via mlc.lib.ms.us.

- ^ Logan 1980, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e f McIntire, Carl (June 20, 1965). "Old, Once Rich, Busy, Rodney Fading Away". Clarion-Ledger. Jackson, Mississippi. p. 57 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Logan 1980, p. 12.

- ^ Rowland, Dunbar, ed. (1925). History of Mississippi, the Heart of the South. Vol. 2. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company. p. 750 – via Google Books.

- ^ Logan 1980, p. 16.

- ^ Haynes, Robert (2010). "Prologue". The Mississippi Territory and the Southwest Frontier, 1795-1817. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-0-8131-7372-6.

- ^ Logan 1980, p. 17.

- ^ Haynes 2010, pp. 132–133

- ^ Logan 1980, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Haynes 2010, p. 157

- ^ Logan 1980, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Logan 1980, p. 19.

- ^ a b Roland, Dunbar, ed. (1907). "Mississippi". Atlanta: Southern Historical Publishing Association. pp. 573–574. Archived from the original on March 4, 2024. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Watson, Keri (Spring 2023). ""You Know Who I Am? I'm Mr. John Paul's Boy"". Southern Cultures. 29 (1). ISSN 1068-8218. Archived from the original on September 29, 2023. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ a b Logan 1980, p. 49.

- ^ Logan 1980, pp. 45–50.

- ^ a b "Reminiscences of Historic Rodney and Oakland College". Tensas gazette. Saint Joseph, Louisiana. Fayette Chronicle. October 15, 1926. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Logan 1980, p. 58.

- ^ Logan 1980, p. 22.

- ^ Watkins, W. H., ed. (n.d.). Some Interesting Facts of the Early History of Jefferson County, Mississippi. No publisher or publication date stated; includes a biography of John A. Watkins by R. S. Albert, two previously published articles by John A. Watkins, and one previously published article by V. N. Russell. p. 15. OCLC 17887012. F347.J42 W3 – via University of Mississippi Libraries Special Collections, Oxford, Mississippi.

- ^ a b Moore, John Hebron (1986). "Two Cotton Kingdoms". Agricultural History. 60 (4): 8, 11. ISSN 0002-1482. JSTOR 3743249. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ James, D. Clayton (1993) [1968]. Antebellum Natchez. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-8071-1860-3. LCCN 68028496. OCLC 28281641.

- ^ "Limerick (J. A.) manuscripts". Mississippi Department of Archives and History, ID: Z/1140.000/F. Manuscript Collections.

- ^ a b Logan 1980, p. 56.

- ^ Logan 1980, p. 57.

- ^ "Oakland College". Mississippi Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on March 4, 2024. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ "Oakland Chapel". Mississippi Department of Archives & History. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "Southern Telegraph (Rodney, Miss.) 1834-1838". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Mississippi: Embracing an Authentic and Comprehensive Account of the Chief Events in the History of the State and a Record of the Lives of Many of the Most Worthy and Illustrious Families and Individuals. Vol. 2. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing. 1891. p. 212.

- ^ "Mar 17, 1836, page 1 - The Rodney Telegraph at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "Conclin's new river guide, or, A gazetteer of all the towns on the western waters : containing sketches of the cities, towns, and countries bordering on the ..." HathiTrust. 1848. p. 102. hdl:2027/uiuo.ark:/13960/t6542sg0x. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ "History of Rodney Mississippi". Archived from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ Wolfe, Brendan. "Anaconda Plan". Encyclopedia Virginia. Archived from the original on March 4, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ "USS Rattler". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Central Arkansas Library System. October 14, 2020. Archived from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Stanley Nelson: The Rattler, the Tensas & Rodney". Concordia Sentinel. September 4, 2019. ISSN 0746-7478. Archived from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ "Little remains from the once prosperous city of Rodney". The Natchez Democrat. May 13, 2009. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ Logan 1980, pp. 58–67, 72, 334.

- ^ Logan 1980, p. 99.

- ^ Logan 1980, p. 98.

- ^ McIntire, Carl (June 20, 1965). "Rodney". Clarion-Ledger. Jackson, Mississippi. p. 64 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Vicksburesque by VBR". The Vicksburg Post. Vicksburg, Mississippi. May 10, 1939. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hendrickson, Paul (1992). Looking for the Light: The Hidden Life and Art of Marion Post Wolcott. Knopf. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-394-57729-6.

- ^ "Rodney, Mississippi, Aug. 1940". NYPL Digital Collections. Archived from the original on March 26, 2024. Retrieved March 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c Pace, Sherry (2007). Historic Churches of Mississippi. Oxford, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. pp. xi, 137–138. ISBN 9781617034091. Archived from the original on March 5, 2024. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Preserving a Mississippi ghost town". The Clarion-Ledger. October 31, 2019. ISSN 0744-9526. Archived from the original on March 4, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ "Church". Grand Gulf Military Park. State of Mississippi. Archived from the original on December 10, 2023. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ Turner-Neal, Chris (August 29, 2016). "Mississippi History Along the Natchez Trace". Country Roads Magazine. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ "Natchez Trace". Mississippi Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ Logan 1980, p. 3.

- ^ Logan 1980, pp. 110–111.

- ^ "James D. Cessor (Jefferson County)". Against All Odds: The first Black legislators in Mississippi. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ "Duggan, Thomas Hinds (1815–1865)". Handbook of Texas. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ "Bill Foster". Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on January 3, 2015. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ^ "Bishop Charles P. Greco, 6th Bishop of Alexandria". Diocese of Alexandria. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ "AHQ: Black Legislators in Arkansas, 231". Southern Arkansas University - Magnolia. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

Further reading

edit- Brookhart, Mary Hughes; Marrs, Suzanne (1986). "More Notes on River Country". The Mississippi Quarterly. 39 (4): 507–519. ISSN 0026-637X. JSTOR 26475367.

- Mitcham, Howard (October 1953). "Old Rodney, a Mississippi Ghost Town". Journal of Mississippi History. 15 (4). Jackson, Mississippi: Mississippi Historical Society in cooperation with the Mississippi Department of Archives and History: 242–251. ISSN 0022-2771. OCLC 1782329.

External links

editMedia related to Rodney, Mississippi at Wikimedia Commons

- "Ghost Town of Rodney". Southpoint Travel Guide. Archived from the original on May 29, 2008. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- "Historical Markers in Rodney, Mississippi".

- Clarke, Joseph C. (January 2005). "Joseph Calvit and His Family in Mississippi". Paper.

- "Church Hill Jefferson County Tidbits #26 & #27 From the WPA Records". Archived from the original on March 21, 2019.