Mansfield is a city in and the county seat of Richland County, Ohio, United States.[4] Located midway between Columbus and Cleveland via Interstate 71, it is part of Northeast Ohio region in the western foothills of the Allegheny Plateau. The 2020 Census showed that the city had a total population of 47,534,[5] making it the 21st-largest city in Ohio. It lies approximately 65 miles (105 km) southwest of Cleveland, 45 miles (72 km) southwest of Akron, and 65 miles (105 km) northeast of Columbus.

Mansfield | |

|---|---|

Skyline of downtown Mansfield | |

| Nickname(s): The Field, the Queen of Ohio | |

| Motto: "The Heart of Ohio" | |

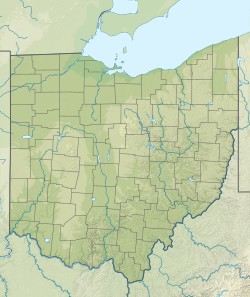

Interactive map of Mansfield | |

| Coordinates: 40°45′12″N 82°30′16″W / 40.75333°N 82.50444°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Ohio |

| County | Richland |

| Founded | June 11, 1808 |

| Incorporated | 1828 (village) |

| – | 1857 (city) |

| Named for | Jared Mansfield |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Mayor | Jodie Perry (R) [1] |

| Area | |

• City | 30.89 sq mi (80.01 km2) |

| • Land | 30.83 sq mi (79.86 km2) |

| • Water | 0.06 sq mi (0.15 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,204 ft (367 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• City | 47,534 |

| • Density | 1,541.66/sq mi (595.23/km2) |

| • Urban | 75,250 (US: 372nd) |

| • Metro | 124,936 (US: 322th) |

| • CSA | 219,408 (US: 130th) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 44900-44999 |

| Area code | 419/567 |

| FIPS code | 39-47138[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1086879[2] |

| Website | www.ci.mansfield.oh.us |

The city was founded in 1808 on a fork of the Mohican River in a hilly region surrounded by fertile farmlands, and became a manufacturing center owing to its location with numerous railroad lines. After the decline of heavy manufacturing, the city's economy has since diversified into a service economy, including retailing, education, and healthcare sectors.

The city anchors the Mansfield Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), which had a population of 124,936 residents in 2020,[6] while the Mansfield–Bucyrus, OH Combined Statistical Area (CSA) had 219,408 residents.[7] Mansfield is the largest city in the Mid-Ohio (north-central) region of the state. Its official nickname is "The Fun Center of Ohio". Mansfield is also known as the "Carousel Capital of Ohio."[8]

Anchored by the Richland Carousel District,[9] downtown Mansfield is home to a number of attractions and arts venues.[10] Concert events in the downtown Brickyard venue have drawn crowds numbering over 5,000 people.[11] Mansfield, in partnership with local and national partners, is addressing blight and economic stagnation in the city center.[12] The Renaissance Performing Arts Association at home in the historic Renaissance Theatre annually presents and produces Broadway-style productions, classical music, comedy, arts education programs, concerts, lectures, and family events to more than 50,000 people. The Renaissance Performing Arts is home of the Mansfield Symphony Orchestra.[13] Downtown is also home to two ballet companies, NEOS Ballet Theatre and Richland Academy Dance Ensemble who both perform and offer community dance opportunities in downtown.[14][15] Mid-Ohio Opera offers performances of full opera and smaller concerts.[16][17][18]

History

editEarly history and founding

editMansfield was laid out and founded by James Hedges, Joseph Larwell, and Jacob Newman, and was platted in June 1808 as a settlement. It was named for Colonel Jared Mansfield, the United States Surveyor General who directed its planning.[19][20]

It was originally platted as a square, known today as the public square or Central Park.[19] During that same year of its founding, a log cabin was built by Samuel Martin on lot 97 (where the H.L. Reed building is now), making it the first and only house to be built in Mansfield in 1808.[19] Martin lived in the cabin during the winter and illegally sold whiskey to Indians, which compelled Martin to flee the country. James Cunningham moved into the cabin in the year of 1809.[21] At that time, there were less than a dozen settlers in Richland County and Ohio was still largely wilderness.[19]

Two blockhouses were erected on the public square during the War of 1812 for protection against the North American colonies and its Indian allies.[19] The block houses were erected in a single night.[22] After the war ended, the first courthouse and jail of Richland County were located in one of two blockhouses until 1816.[19][23] The blockhouse was later used as a school with Eliza Wolf being its teacher.[24] Mansfield was incorporated as a village in 1828 and then as a city in 1857 with a population of 5,121.[25] Between 1846 and 1863, the railroads came to the city with the Sandusky, Mansfield and Newark Railroad being the first railroad to reach Mansfield in 1846, the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne and Chicago Railway in 1849, and the Atlantic and Great Western Railroad in 1863.[26] The city was a center of manufacturing and trade in the late 1880s thanks to the four railroads that passed through the community.

Dozens of manufacturing businesses operated in the city, producing goods like brass objects, doors, linseed oil, paper boxes, suspenders, and numerous other items. Mansfield's largest employer in 1888 was a cigar maker, Hautzenroeder & Company, that had 285 workers employed.[27] In 1888, Frank B. Black borrowed $5,000 from relatives to start a brass foundry, the Ohio Brass Company, specializing in brass and bronze castings, stem brass goods, electric railway supplies and more.[28] By 1890, 13,473 people lived in the city.

20th and 21st centuries

editBy 1908, the blockhouse became a symbol of Mansfield's heritage during its 100th birthday celebration, and in 1929, the blockhouse was relocated to its present location at South Park.[19][23]

The Mansfield Tire and Rubber Company was founded in the city in 1912, producing tires for automobiles.[29]

During the 1920s and 1930s, the Mansfield tire brand stood shoulder to shoulder with Goodyear, Goodrich, Firestone and Uniroyal, the "Big Four" tire name brands in the industry at the time.[29] The Mansfield Tire and Rubber Company continued to grow through the 1950s and 1960s, before its production started to decline in the 1970s.[29] The company declared bankruptcy in the early 1980s, after closing in 1979, leaving 1,721 workers out of a job.[29][30]

In 1913, parts of Mansfield were flooded when the Great Flood of 1913 brought 3 to 8 inches (76 to 203 mm) of rainfall across Ohio between March 24 and 25.[31][32] The first road across America, the Lincoln Highway, came to the city in 1913, smoothing the path for economic growth.[33] In 1924, Oak Hill Cottage, a Gothic Revival brick house, built in 1847 by John Robinson, superintendent of the Sandusky, Mansfield and Newark Railroad was the setting of The Green Bay Tree, Mansfield native Louis Bromfield's first novel.[34]

In 1927, the 9-story Leland Hotel was constructed downtown on the southwest corner of Park Avenue West and South Walnut Street at a cost of $556,000.[35] The Leland Hotel was the tallest building in Mansfield when completed, and was designed by architect Vernon Redding, that also designed the Mansfield Public Library, Farmers Bank Building, Mansfield Savings Bank Building and Mansfield General Hospital.[35] The hotel was razed in 1976 to make way for a parking lot.[35][36] What remains of the Leland Hotel today is the hotel's compass rose that was embedded in the sidewalk along Walnut Street where the front door of the hotel once was.[35]

Like many cities in the Rust Belt, the 1970s and 1980s brought urban blight, and losses of significant household name blue-collar manufacturing jobs.[37] In recent years, Mansfield's downtown, which once underscored the community's economic difficulties, has seen innovative revitalization through the establishment of Main Street Mansfield (known today as Downtown Mansfield, Inc.), and is a site of new business growth.[37][38] In 1993, Lydia Reid was sworn in as the city's first female mayor and became the longest-serving mayor of Mansfield encompassing three four-year terms.[39] Reid was succeeded in 2007 by Donald Culliver, the city's first black mayor.[40]

In December 2009, the city was placed on fiscal watch by the state auditor citing substantial deficit balances in structural operating general funds.[41] On August 19, 2010, Mansfield would become Ohio's largest city to be declared in fiscal emergency with a deficit of $3.8 million after city officials failed to pass measures on cost-savings and cut spending, blaming it on the Great Recession.[41][42] The city's financial crisis lasted nearly four years before being lifted out of fiscal emergency on July 9, 2014.[43]

Geography

editTopography

editMansfield is located at 40°45′17″N 82°31′22″W / 40.75472°N 82.52278°W (40.754856, −82.522855),[44] directly between Columbus and Cleveland, however, the city lies in the western foothills of the Allegheny Plateau, and its elevation is among the highest of Ohio cities. The highest point in the city 1,493 feet (455 m) above sea level is located at the Woodland Reservoir, an underground water storage (service reservoir) along Woodland Road in southwest Mansfield. The elevation in downtown Mansfield, which is located at Central Park is 1,240 feet (378 m) above sea level, and at Mansfield Lahm Airport, the elevation is 1,293 feet (394 m) above sea level.[45] The highest point in Richland County, second highest point in Ohio (after Campbell Hill) is between 1,510 feet (460 m) and 1,520 feet (463 m) above sea level is located southwest of the city, just off Lexington-Ontario Road at Apple Hill Orchards in Springfield Township.[46]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 30.92 square miles (80.08 km2), of which, 30.87 square miles (79.95 km2) is land and 0.05 square miles (0.13 km2) is water.[47]

Mansfield is bordered by Madison Township to the east, northwest and southwest, Franklin Township to the north, Weller Township to the northeast, Washington Township to the south, Troy Township to the southwest, Springfield Township and the suburban city of Ontario to the west.

Climate

editMansfield has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa), typical of the Midwest, with four distinct seasons.[48] The city is located in USDA hardiness zones 5b (-15 °F to -10 °F) and 6a (-10 °F to -5 °F).[49] Winters are cold and dry but typically bring a mix of rain, sleet, and snow with occasional heavy snowfall and icing. January is the coldest month with an average mean temperature of 26.5 °F (−3 °C),[48] with temperatures dropping to or below 0 °F (−18 °C) 5 days per year on average.[48] Snowfall is lighter than in the snowbelt areas to the northeast, but is still somewhat influenced by Lake Erie, located 38 miles (61 km) north of the city. Snowfall averages 49.2 inches (125 cm) per season.[48] The greatest 24-hour snowfall was 23 inches (58 cm) on December 22–23, 2004 when the city was impacted by a major ice storm following the Pre-Christmas 2004 snowstorm, bringing with it a band of freezing rain and sleet led by ice and snow accumulations.[50] Another notable snowstorm to impact the region was the Great Blizzard of 1978. The snowiest month on record was 52.5 inches (133 cm) in February 2010, while winter snowfall amounts have ranged from 91.0 in (231 cm) in 1995–96 to 12.5 in (32 cm) in 1932–33.[51] Springs are short with rapid transition from hard winter to sometimes very warm, and humid conditions. Summers are typically very warm, sometimes hot, and humid with temperatures exceeding 90 °F (32 °C) 8 days per year on average.[48] July is the warmest month with an average mean temperature of 72.6 °F (23 °C).[48] Fall usually is the dryest season with many clear warm days and cool nights. Severe Thunderstorms are not uncommon during the spring, summer, and fall bring with them the threat of large hail, damaging winds and in rare cases tornadoes. Flooding can also occur from time to time such as the 2007 Midwest flooding that took place in the region on August 20–21, 2007 when Mansfield received 6.24 inches (158 mm) of rain in 24 hours.[52] Monthly precipitation has ranged from 13.23 in (336 mm) in July 1992 to 0.25 in (6.4 mm) in December 1955, while for annual precipitation the historical range is 67.22 in (1,707 mm) in 1990 to 21.81 in (554 mm) in 1963.[51]

The all-time record high temperature in Mansfield of 105 °F (41 °C) was established on July 21, 1934, which occurred during the Dust Bowl drought of the 1930s, and the all-time record low temperature of −22 °F (−30 °C) was set on January 20, 1985, and January 19, 1994.[48] The first and last freezes of the season on average fall on October 19 and April 27, respectively, allowing a growing season of 174 days.[48] The normal annual mean temperature is 50.6 °F (10.3 °C).[48] Normal yearly precipitation based on the 30-year average from 1991 to 2020 is 42.49 inches (1,079 mm), falling on an average 150 days.[48]

| Climate data for Mansfield, Ohio (Mansfield Lahm Airport), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1899–present[a] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 69 (21) |

74 (23) |

84 (29) |

87 (31) |

95 (35) |

101 (38) |

105 (41) |

103 (39) |

97 (36) |

90 (32) |

79 (26) |

73 (23) |

105 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 57.5 (14.2) |

59.5 (15.3) |

69.7 (20.9) |

79.2 (26.2) |

85.9 (29.9) |

90.7 (32.6) |

90.8 (32.7) |

89.6 (32.0) |

87.4 (30.8) |

80.2 (26.8) |

68.1 (20.1) |

59.0 (15.0) |

92.1 (33.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 34.0 (1.1) |

37.0 (2.8) |

46.9 (8.3) |

60.4 (15.8) |

71.1 (21.7) |

79.4 (26.3) |

82.8 (28.2) |

81.2 (27.3) |

75.0 (23.9) |

62.8 (17.1) |

49.6 (9.8) |

38.6 (3.7) |

59.9 (15.5) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 26.5 (−3.1) |

29.1 (−1.6) |

37.8 (3.2) |

49.7 (9.8) |

60.3 (15.7) |

69.0 (20.6) |

72.6 (22.6) |

71.0 (21.7) |

64.4 (18.0) |

53.0 (11.7) |

41.5 (5.3) |

31.8 (−0.1) |

50.6 (10.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 19.1 (−7.2) |

21.2 (−6.0) |

28.7 (−1.8) |

38.9 (3.8) |

49.6 (9.8) |

58.6 (14.8) |

62.3 (16.8) |

60.8 (16.0) |

53.7 (12.1) |

43.1 (6.2) |

33.4 (0.8) |

25.0 (−3.9) |

41.2 (5.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −2.3 (−19.1) |

2.1 (−16.6) |

10.2 (−12.1) |

23.4 (−4.8) |

34.8 (1.6) |

44.3 (6.8) |

51.2 (10.7) |

49.5 (9.7) |

39.7 (4.3) |

29.0 (−1.7) |

17.6 (−8.0) |

6.5 (−14.2) |

−5.3 (−20.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −22 (−30) |

−21 (−29) |

−20 (−29) |

8 (−13) |

20 (−7) |

32 (0) |

40 (4) |

32 (0) |

22 (−6) |

17 (−8) |

−17 (−27) |

−20 (−29) |

−22 (−30) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.22 (82) |

2.53 (64) |

3.34 (85) |

4.27 (108) |

4.19 (106) |

4.79 (122) |

3.86 (98) |

3.60 (91) |

3.36 (85) |

3.16 (80) |

3.15 (80) |

3.02 (77) |

42.49 (1,079) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 14.5 (37) |

12.7 (32) |

7.6 (19) |

1.9 (4.8) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.5 (1.3) |

2.3 (5.8) |

9.7 (25) |

49.2 (125) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 15.8 | 13.4 | 14.0 | 14.6 | 14.2 | 12.7 | 10.8 | 10.2 | 9.6 | 11.3 | 11.7 | 14.3 | 152.6 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 11.3 | 9.3 | 6.1 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 7.7 | 39.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76.1 | 73.5 | 70.7 | 65.2 | 68.0 | 71.3 | 71.4 | 74.8 | 74.8 | 70.2 | 74.8 | 78.0 | 72.4 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity 1961–1990)[b][48][53][54][55] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

editThis section needs to be updated. The reason given is: Demographic data from the 2020 Census is now available. (November 2021) |

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1820 | 288 | — | |

| 1830 | 840 | 191.7% | |

| 1840 | 1,328 | 58.1% | |

| 1850 | 3,557 | 167.8% | |

| 1860 | 4,581 | 28.8% | |

| 1870 | 8,029 | 75.3% | |

| 1880 | 9,859 | 22.8% | |

| 1890 | 13,473 | 36.7% | |

| 1900 | 17,640 | 30.9% | |

| 1910 | 20,768 | 17.7% | |

| 1920 | 27,824 | 34.0% | |

| 1930 | 33,525 | 20.5% | |

| 1940 | 37,154 | 10.8% | |

| 1950 | 43,564 | 17.3% | |

| 1960 | 47,325 | 8.6% | |

| 1970 | 55,047 | 16.3% | |

| 1980 | 53,927 | −2.0% | |

| 1990 | 50,627 | −6.1% | |

| 2000 | 49,346 | −2.5% | |

| 2010 | 47,821 | −3.1% | |

| 2020 | 47,534 | −0.6% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[56] 2020 census[5] | |||

2010 census

editAs of the census[57] of 2010, there were 47,821 people, 18,696 households, and 10,655 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,549.1 inhabitants per square mile (598.1/km2). There were 22,022 housing units at an average density of 713.4 per square mile (275.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 73.3% White, 22.1% African American, 0.2% Native American, 0.7% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.5% from other races, and 3.0% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.9% of the population.

There were 18,696 households, of which 27.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.0% were married couples living together, 16.6% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.4% had a male householder with no wife present, and 43.0% were non-families. 37.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.21 and the average family size was 2.88.

The median age in the city was 38.5 years. 20.2% of residents were under the age of 18; 10.1% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 28% were from 25 to 44; 26% were from 45 to 64; and 15.7% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 53.0% male and 47.0% female.

2000 census

editAs of the census[3] of 2000, there were 49,346 people, 20,182 households, and 12,028 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,649.8 inhabitants per square mile (637.0/km2). There were 22,267 housing units at an average density of 744.6 per square mile (287.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 76.77% White, 19.65% African American, 0.28% Native American, 0.63% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 0.56% from other races, and 2.07% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.23% of the population.[58]

There were 20,182 households, out of which 27.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.5% were married couples living together, 15.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 40.4% were non-families. 34.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.28 and the average family size was 2.93.[58]

In the city the population was spread out, with 23.9% under the age of 18, 9.3% from 18 to 24, 29.7% from 25 to 44, 21.7% from 45 to 64, and 15.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 98.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.1 males.[58]

The median income for a household in the city was $30,176, and the median income for a family was $37,541. Males had a median income of $30,861 versus $21,951 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,726. About 13.2% of families and 16.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 24.5% of those under age 18 and 9.6% of those age 65 or over.[58]

Languages

editAs of 2000, speakers of English accounted for 95.98% of residents, Spanish by 1.46%, German by 1.11%, and French speakers comprised 0.56% of the population.[59]

Other languages that were spoken throughout the city include Chinese at 0.21%, Italian at 0.17%, Japanese at 0.11%, and Greek at 0.10% of the population.[59] Mansfield also has a small percentage of residents who speak first languages other than English at home (4.02%).[59]

Law and government

editMansfield has a mayor-council government. The mayor who is elected every four years, always in November, one year before United States presidential elections and limited to a maximum of three terms. Mayors are traditionally inaugurated on or around the first of December. The current mayor is Jodie Perry, a Republican, elected in 2023.[1]

Mansfield city council is an eight-member legislative group that serve four-year terms. Six of the members represent specific wards; two are elected citywide as at-large council members.[60] Democrat Phillip Scott has been Mansfield's council president since January 2024.[61][62] The members of the city council are:

| Ward | City Council Member | Ward | City Council Member |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Ward | Laura Burns[63] | 5th Ward | Aurelio Diaz[64] |

| 2nd Ward | Cheryl Meier[65] | 6th Ward | Deborah Mount[66] |

| 3rd Ward | Eleazer Akuchie[67] | At-Large | David Falquette[68] |

| 4th Ward | Antoinette Daley[69] | At-Large | Stephanie Zader[70] |

The city is represented in the Ohio House of Representatives by Marilyn John (R) from the 76th district; in the Ohio Senate by Mark Romanchuk (R) from the 22nd Ohio Senate District; in the U.S. House of Representatives by Jim Jordan (R) from Ohio's 4th congressional district; and in the U.S. Senate by Sherrod Brown (D) and J. D. Vance (R).

Crime

editThe City of Mansfield is policed by a Municipal Police Department, the Mansfield Division of Police.[71] According to the FBI statistics, Mansfield has a high violent crime rate. Mansfield's crime rate is worse than 89.5% higher than other cities in the United States. Property crime rate was more than double the state average. There were 187 violent offenses, 3 murders, 48 forcible rapes, 38 robberies and 98 aggravated assaults that were reported in 2019, compared with 1,996 property crimes (396 burglaries, 1,523 larceny-thefts, 77 motor vehicle thefts and 17 incidents of arson) that were reported that same year.[72] Neighborhoodscout.com reported a crime rate of 42.83 per 1000 residents for property crimes, and 4.01 per 1000 for violent crimes in 2019 (compared to national figures of 21.11 per 1000 for property crimes and 3.8 per 1000 for violent crimes in 2019).[72]

Economy

edit| Top Employers based in Mansfield, Ohio Source: Richland Community Development Group[73] | |||||

| Rank | Company/Organization | # | |||

| 1 | OhioHealth (formerly MedCentral) | 2,500 | |||

| 2 | Richland County | 1,474 | |||

| 3 | Newman Technology | 1,100 | |||

| 4 | Jay Industries | 943 | |||

| 5 | Gorman-Rupp Company | 809 | |||

| 6 | CenturyLink | 800 | |||

| 7 | Therm-O-Disc | 721 | |||

| 8 | Mansfield Board of Education | 700 | |||

| 9 | DOFASCO Corp. (Copperweld) | 666 | |||

| 10 | Mansfield Correctional Institution (MANCI) | 621 | |||

| 11 | City of Mansfield | 575 | |||

| 12 | Richland Correctional Institution (RICI) | 443 | |||

| 13 | AK Steel Corp. | 389 | |||

| 14 | School Specialty, Inc. | 381 | |||

| 15 | Walmart | 314 | |||

| 16 | Kroger | 300 | |||

| 17 | 179th Airlift Wing | 275 | |||

Mansfield's greatest period of industrial development was led by the city's home appliances and stove manufacturing industries, including Westinghouse Electric Corporation and the Tappan Stove Company.[74][75] Westinghouse was the city's largest employer in the late 1950s, with over 8,000 employees, specializing in electric lighting, industrial heating and engineering, and home appliances.[75] In 1990, when Westinghouse was known as Mansfield Products Company (Laundry Division of White-Westinghouse), there were 643 employed when it closed.[75]

However, like many cities in the rust belt, Mansfield experienced a large decline in its manufacturing and retail sectors. Beginning with the steel Recession of the 1970s, the loss of jobs to overseas manufacturing, prolonged labor disputes, and deteriorating factory facilities all contributed to heavy industry leaving the area. Mansfield Tire and Rubber Company,[29] Ohio Brass Company,[28] Westinghouse,[75] Tappan and many other manufacturing plants were either bought-out, relocated or closed, leaving only the AK Steel plant in Mansfield as the last remaining heavy industry employers. The AK Steel Mansfield Works production facility, formerly Armco Steel, was the location of a violent 3-year United Steelworkers Union lock-out and strike from 1999 to 2002.[76] On June 1, 2009, General Motors filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection and announced that its Ontario stamping plant (Mansfield-Ontario Metal Center) would close in June 2010.[77]

With the loss of the jobs, locally owned businesses in downtown Mansfield closed, as did much of the retail built in the 1960s along Park Avenue West (formerly known as "The Miracle Mile") and Lexington Avenue. New big-box retail, shopping strips and franchise restaurants have been built in the adjacent suburban city of Ontario, which has replaced Mansfield as the retail hub for Richland County and north-central Ohio.

The city has sought to diversify its economy to become less dependent on its struggling manufacturing sector. Remaining manufacturers in Mansfield include steel manufacturer AK Steel, Honda supplier Newman Technology Incorporated, generator manufacturer Ideal Electric Company (formerly Hyundai Ideal Electric Company),[78] thermostats manufacturer Therm-O-Disc,[79] pumps manufacturer The Gorman-Rupp Company,[80] carousel manufacturer The Carousel Works, Inc.,[81] business process outsourcing company StarTek,[82] educational products supplier School Specialty, Inc. has a distribution center in Mansfield,[83] and Mansfield Engineered Components,[84] a designer and manufacturer of motion control components for the appliance, transportation, medical casegoods and general industrial markets. Mansfield's healthcare industry includes OhioHealth (formerly MedCentral Health System), the city's largest employer and the largest in Richland County.[85] The hospital is the city's primary provider of health care and serves as the major regional trauma center for north-central Ohio.[86]

Mansfield is also home of three well-known food companies. Isaly Dairy Company (AKA Isaly's) was a chain of family-owned dairies and restaurants started by William Isaly in the early 1900s until the 1970s, famous for creating the Klondike Bar ice cream treat, popularized by the slogan "What would you do for a Klondike Bar?". Stewart's Restaurants is a chain of root beer stands started by Frank Stewart in 1924, famous for their Stewart's Fountain Classics line of premium beverages now sold worldwide. The Jones Potato Chip Company, started by Frederick W. Jones in 1945 and famous for their Jones Marcelled Potato Chips, is headquartered in Mansfield.[87]

Film industry

editFrom the 1950s through the 1970s, Mansfield was the home of the infamous Highway Safety Foundation, the organization that created the controversial driver's education scare films that featured gruesome film photography taken at fatal automobile accidents in the Mansfield area.[88] The films include Signal 30 (1959), Mechanized Death (1961), Wheels of Tragedy (1963), and Highways of Agony (1969). In addition, the Highway Safety Foundation produced other controversial education films including The Child Molester and Camera Surveillance (both 1964).

In 1962, The Highway Safety Foundation loaned camera equipment to the Mansfield Police Department to film the escapades of some of the city's homosexual men, who met for sexual relations in an underground public restroom on the north side of Central Park. The men filmed were charged under Ohio's sodomy law, and all served a minimum of one year in the state penitentiary. The resulting footage, combined with overdubbed audio commentary by officials of the Mansfield Police Department, was eventually compiled by HSF as the 1964 film Camera Surveillance. Video artist William E. Jones of Massillon, Ohio, obtained copies of the original footage shot by the Mansfield Police Department. Jones transferred the grainy color footage of the original police surveillance films to video and removed the police commentary, presenting it as a silent piece entitled Tearoom (2007). Jones' film was featured in an exhibit at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York in 2008.

Mansfield has also been used as a location for several big-budget Hollywood movies; among the most notable of these were The Shawshank Redemption,[89] Air Force One, and Tango & Cash, all of which featured the Ohio State Reformatory as a backdrop in pivotal scenes.

Robert F. Simon (1908–1992), an American character actor who appeared in film and on television from 1950 to 1985, was born in Mansfield.

Culture

editAnnual events and fairs

editThe Mansfield/Mehock Relays, an annual two-day invitational track and field meet for high school boys and girls, held in April since 1927 (except for Second World War years), began on the initiative of Harry Mehock, track coach at host Mansfield Senior High School.

The Miss Ohio Pageant (Miss America preliminary), hosted by Mansfield since 1975, is staged annually at The Renaissance.[91]

The Richland County Fair is also held in Mansfield, at the Richland County Fairgrounds.[92] The fair is held in the beginning of August. The fair started on October 26, 1849.[93] In 1872 and 1873, Mansfield also hosted the Ohio State Fair.[93] At the fair there are several rides, livestock judging.

Annual masterclasses given by world-famous master musicians are presented by Mid-Ohio Opera. They are hosted by The Ohio State University Mansfield in the John and Pearl Conard Performance Hall.

Historical structures and museums

editMansfield is home to the old Ohio State Reformatory, constructed between 1886 and 1910 to resemble a German castle. The supervising architect was F. F. Schnitzer, who was responsible for construction and was presented with a silver double inkwell by the governor of the state in a lavish ceremony to thank him for his services.[94] The reformatory is located north of downtown Mansfield on Ohio 545, and has been the location for many major films,[95] including The Shawshank Redemption, Harry and Walter Go to New York, Air Force One and Tango & Cash.[96]

Most of the prison yard has now been demolished to make room for expansion of the adjacent Mansfield Correctional Institution and Richland Correctional Institution, but the Reformatory's Gothic-style Administration Building remains standing and due to its prominent use in films, has become a tourist attraction. The building is used during the Halloween season each year as a haunted attraction known as the "Haunted Reformatory". Many people visit Mansfield to take part in the haunted tour, some from as far as Michigan and Indiana.[96][97]

Located in the heart of downtown, the Mansfield Memorial Museum, built in 1887, and opened to the public in 1889 as the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall, is a museum of many different exhibits.[98] Oak Hill Cottage, located amongst the ruins of Mansfield's once mighty industrial district, is a Gothic Revival brick house, built in 1847. One of the most perfect Carpenter Gothic houses in the United States, it is operated by the Richland County Historical Society.[34] Located in the Woodland neighborhood, the Mansfield Art Center, opened in 1945, is a visual arts organization.[99] BibleWalk (formerly The Living Bible Museum), opened in 1987, is Ohio's only life-size wax museum.[100] The Bissman Building (known as the Bissman Block), built in 1886, used to be open for tours from March to November until they were discontinued in 2019.[101]

Parks and outdoor attractions

editMansfield has 33 parks ranging in size from the one-half-acre (2,000 m2) Betzstone Park to the 35-acre (140,000 m2) South Park.[102] There are also several public golf courses in and around the city. These include Coolridge Golf Course, Forest Hills, Oaktree, Twin Lakes and Wooldridge Woods Golf and Swim Club.[103]

Located in downtown Mansfield's Historic Carousel District is the Richland Carousel Park, opened in 1991. It is the first hand-carved indoor wooden carousel to be built and operated in the United States since the early 1930s. It was built by Carousel Works Inc.[104][105] Kingwood Center, a 47-acre (19 ha) estate and gardens, is the former home of Ohio Brass industrialist Charles Kelly King.[106][107] Snow Trails Ski Resort is Ohio's oldest ski resort, opened in 1961, and highest at 1,475 feet (450 m). With 16 runs, it is one of the few skiing locations in Ohio.[108]

The Richland B&O Bike Trail, opened in 1995 and operated by the Richland County Park District, is a paved 18.3-mile (29.5 km) hiking and bicycle trail laid out on the abandoned Baltimore & Ohio rail branch line from Butler via Bellville and Lexington to North Lake Park in Mansfield.[109]

Performing arts

editThe Renaissance Theatre, built in 1927 and opened in 1928 as the Ohio Theatre, is a historic 1,402 seat movie palace theatre located in downtown Mansfield that presents and produces a range of arts and cultural performances, and is the home of the Miss Ohio Pageant (Miss America preliminary) and the Mansfield Symphony.[110]

Mid-Ohio Opera is an opera production company based in downtown Mansfield, Ohio. Started in 2014, Mid-Ohio Opera produces operas and classical vocal concerts in the original languages.[111]

The downtown area is the home of the Mansfield Playhouse, founded in 1929 is Ohio's second oldest, and one of its most successful, community theatres.[112]

Safety Town

editIn 2018 the city celebrated the 80th anniversary of Safety Town, a free program developed in Mansfield for pre-kindergarten children about pedestrian safety. Over the years the program, through the efforts of the National Safety Town Center, has been improved to include all aspects of child safety. Programs operate in over 4,000 communities in the US and 38 other countries.

Media

editMansfield is served in print by the Mansfield News Journal, the city's daily traditional newspaper,[113] and the Richland Source, a digital newspaper.[114]

A defunct newspaper is the Mansfield Shield, which ran from 1892 to 1912 as the Mansfield Daily Shield, and then from 1912 to 1913 as the Mansfield Shield.[115]

TV

editThe Mid-Ohio region—which encompasses Mansfield—has only one locally targeted full power television station, which is WMFD-TV 68, the first independent digital station in America.[116] The station provides Mid-Oho focused newscasts, local interest shows, and high school sports telecasts.

Mansfield—being halfway between Cleveland and Columbus—is also served (albeit at a fringe level) by stations in those markets as well.

Radio

edit16 stations directly serve the Mansfield/Ashland (Mid-Ohio) area. Music stations include adult contemporary stations WVNO-FM and WQIO, WFXN-FM (Classic Rock), WYHT (Hot AC), WNCO-FM (Country), WSWR FM (Classic hits), WXXF (Soft AC), Christian contemporary stations WVMC-FM and WYKL (K-Love), WOSV (classical music – repeater of WOSA Columbus) and WRDL (Contemporary hits - owned by Ashland University).

WMAN AM/FM serve as the market's only news/talk outlets. WRGM 1440 AM/106.7 FM (ESPN) and WNCO (Fox) both have sports/talk formats, and WFOT (EWTN) provides a religious format as a repeater of WNOC Toledo

Mansfield's first AM-radio station (1926) was WLGV (later WJW Mansfield). The Mansfield studio and transmitter were on the ninth floor of the Richland Trust Building. WJW moved to Akron in 1932. The WJW call letters were later reassigned WJW, based in Cleveland (now WKNR).

Education

editMansfield Public Schools enroll 4,591 students in public primary and secondary grades.[117] The district has 8 public schools including one Spanish immersion school, two elementary schools, one intermediate school, one middle school, one high school, and one alternative school. Other than public schools, the city is home to two private Catholic schools, St. Mary's Catholic School and St. Peter's High School along with St. Peter's Junior High and St. Peter's Elementary School and two Christian schools, Mansfield Christian School and Temple Christian School. Discovery School, an International Baccalaureate candidate school, is the only non denominational private school in this area. The Madison Local School District serves eastern parts of Mansfield, neighboring Madison Township, most of Mifflin Township, and parts of Washington Township.[118]

Mansfield is home to three institutions of higher learning. The Ohio State University has a regional campus at Mansfield,[119] North Central State College, a community college that shares the Mansfield Campus with OSU,[120] and Ashland University's Dwight Schar College of Nursing & Health Sciences, a newly constructed 46,000-square-foot academic and nursing building that opened for classes on August 20, 2012, is a private institution of higher education, located on the university's Balgreen Campus at Trimble Road and Marion Avenue in Mansfield, offering programs of study leading to the baccalaureate degree in nursing.[121]

The Mayor's Education Task Force was founded created in October 2008 in a response to the district's academic emergency status and low community support for the Mansfield City Public School system.[122]

OSU-Mansfield, in 1989, hosted a weekend school for Japanese students.[123]

Libraries

editThe Mansfield/Richland County Public Library (M/RCPL) has been serving residents of north-central Ohio since 1887.[124] The system has nine branches throughout Richland County including the main library in downtown Mansfield and locations in Bellville, Butler, Crestview, Lexington, Lucas, Madison Township, Ontario, and Plymouth.

Transportation

editHighways and roads

editMansfield is located on a major east–west highway corridor that was originally known in the early 1900s as "Ohio Market Route 3". This route was chosen in 1913 to become part of the historic Lincoln Highway which was the first road across America, connecting New York City to San Francisco. The arrival of the Lincoln Highway to Mansfield was a major influence on the development of the city. Upon the advent of the federal numbered highway system in 1928, the Lincoln Highway through Mansfield on Park Avenue East and Park Avenue West became U.S. Route 30.

On September 1, 1928, the Lincoln Highway was marked coast-to-coast with approximately 3000 concrete posts set by the Boy Scouts of America. Each post featured a medallion of Abraham Lincoln's profile. One of these concrete markers was erected at curbside in front of Central Methodist Episcopal Church, 378 Park Avenue West. It now stands in downtown's Central Park, on Park Avenue's center divider. The Lincoln Highway Association observed the highway's centennial in June 2013. The celebration's eastern transcontinental tour group visited Mansfield for an overnight stay on June 25 at the Holiday Inn on Park Avenue West, the highway's route through the city.

Mansfield is connected to the Interstate Highway System. Three highway exits from Interstate 71 connects Mansfield to Columbus, Ohio, Cincinnati, Ohio, Louisville, Kentucky, and points southwest, and to Cleveland, Ohio, to the northeast.

One limited-access highway serves Mansfield. U.S. Route 30, which carries the Martin Luther King Jr. Freeway along its length through the city has several local highway exits from U.S. Route 30 connects Mansfield to Bucyrus, Ohio, Fort Wayne, Indiana, and points west, and to Wooster, Ohio, Canton, Ohio, and points east.

Two divided highways serve Mansfield. Ohio 309, which connects travelers from the major shopping area of the suburban city of Ontario and points west, and continues east into Mansfield before it merges into U.S. Route 30. Ohio 13 turns into a four-lane divided highway at South Main Street and Chilton Avenue and runs 3.5 miles (5.6 km) to Interstate 71 (full-access interchange) and runs another 3.7 miles (6.0 km) and turns back into a two-lane highway just 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Bellville.

The city has several arterial roads. U.S. Route 42 (Ashland Road and Lexington Avenue), North U.S. Route 42 downtown (South Main Street, East 2nd Street, Hedges Street and Park Avenue East), South U.S. Route 42 downtown (Park Avenue East, Hedges Street, East 1st Street and South Main Street), Ohio 13 (North Main Street and South Main Street), North Ohio 13 downtown (East 2nd Street, South Diamond Street and North Diamond Street), South Ohio 13 downtown (West 5th Street, North Mulberry Street, South Mulberry Street and West 1st Street), Ohio 39 (Springmill Street, North Mulberry Street, West 5th Street, East 5th Street, Park Avenue East and Lucas Road), Ohio 430 (Park Avenue East and Park Avenue West), and Ohio 545 (Wayne Street and Olivesburg Road).[103]

Designated truck routes known as Truck U.S. Route 42/Truck Ohio 430 (Adams Street and East 5th Street) exist around the downtown area for semi-tractor-trailer trucks due to the 12 ft (3.7 m) height clearance at the Norfolk Southern Railway subway overpass (also known to locals as the Park Avenue East underpass or the subway) that was constructed in 1924 passes over U.S. Route 42/Ohio 430 (Park Avenue East).[125] According to city officials, trucks that happen to be over 12 ft (3.7 m) get stuck under the subway about five to six times a year on average due to not following advanced warning signage.[125] Ohio 13 also has a truck route known as Truck Ohio 13 north (East 1st Street, Adams Street and East 5th Street) and Truck Ohio 13 south (East 5th Street, Adams Street and East 2nd Street) to help keep semi-truck traffic out of downtown Mansfield's Historic Carousel District.

Public transportation

editThe Richland County Transit (RCT) operates local bus service five days a week, except for Saturdays and Sundays. The RCT bus line operates 9 fixed routes within the cities of Mansfield and Ontario along with fixed routes extending into the city of Shelby and Madison Township.[126] Mansfield Checker Cab operates local and regional taxi service 24 hours a day, seven days a week.[127] C & D Taxi also operates local and regional taxi service (Richland and Ashland Counties) seven days a week.

Airports

editMansfield Lahm Regional Airport (IATA: MFD, ICAO: KMFD, FAA LID: MFD), a city-owned and operated, joint usage facility with global ties, located 3 miles (4.8 km) north of downtown Mansfield.[128] The Mansfield Lahm Air National Guard Base and the 179th Airlift Wing of the Ohio Air National Guard is located at the airport. It uses huge C-130 aircraft, and sponsors an annual air show in July.[129]

Downtown Mansfield is roughly centrally located between both John Glenn Columbus International Airport and Cleveland Hopkins International Airport, both of which offering moderate choices for commercial flights. Akron–Canton Airport is located closer to Mansfield, but does not have any international flights unlike Columbus and Cleveland.

Railroads

editThree railroads previously served Mansfield, but currently only two, the Norfolk Southern and the Ashland Railway,[130] provide service in the area.

The Sandusky, Mansfield and Newark Railroad opened in 1846 and became part of the Washington-Chicago main line of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) and then later part of a B&O branch line from Newark to Sandusky. In 1849 the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne and Chicago Railway (later Pennsylvania Railroad mainline) reached Mansfield, and in 1863 the Atlantic and Great Western Railroad (later Erie Railroad mainline) reached Mansfield.

Passenger services operating into the opening of the 1970s were the Erie Lackawanna's Chicago-Hoboken, New Jersey Lake Cities (discontinued, 1970); and the Penn Central's Manhattan Limited and Pennsylvania Limited (both discontinued, 1971, at the transfer over to Amtrak).

After the B&O branch line was abandoned, the 18.3-mile (29.5 km) section from Butler to North Lake Park in Mansfield was opened in 1995 as the recreational Richland B&O Trail.[109] The former B&O track from Mansfield to Willard combined with a piece of the abandoned Erie Railroad east of Mansfield to West Salem to form the L-shaped 56.5-mile (90.9 km) Ashland Railway (1986). A spur of the abandoned Erie Railroad leads west 5 miles (8.0 km) to Ontario to what used to be the General Motors metal stamping plant there.

Special interest

edit- In 1962, the Mansfield Police Department conducted a sting operation in which they covertly filmed men having sex in the public restroom underneath Central Park. Thirty eight men were convicted and jailed for sodomy. After the arrest, the city closed the restrooms and filled them in with dirt. The police later made a training film of the footage. The artist William E. Jones used the original footage in his 2007 film Tearoom.[131]

- Johnny Appleseed, American pioneer and conservationist, is considered to be from Mansfield.[132]

Sister cities

editMansfield has sister city relationships with:[133]

- – Mansfield, Nottinghamshire, United Kingdom[134]

- – Tamura, Fukushima, Japan

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Perry sworn in as mansfield mayor Directory". richlandsource.com. December 22, 2023.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Mansfield, Ohio

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ Table of United States Metropolitan Statistical Areas

- ^ "U.S. Population – Combined Statistical Area Population". Weblists. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ "In the Heartland: An Ohio Road Trip by RV, Part II by Harry Basch & Shirley Slater". frommers.com. July 25, 2002. Retrieved September 8, 2006.

- ^ "Welcome to the historic Carrousel District". The Historic Carrousel District & Downtown Mansfield. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ Battishill, Missy Loar and Glenn. "Carrousel gives Mansfield's downtown district another ride". The Collegian. Archived from the original on May 10, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ "Bandstand coming to Brickyard". Mansfield News Journal. April 28, 2015. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ "Mansfield, Ohio —PR Project œ Path to Revitalization" Brownfield Initiative œ A National Model" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 22, 2016.

- ^ "New batons to lead Mansfield Symphony, Chorus". Richland Source. April 21, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ "Neos Center for Dance announces fall quarter classes". Richland Source. August 29, 2014. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ "Cleveland Ballet makes admirable debut in partnership with Neos Dance Theatre (review)". cleveland.com. October 6, 2015. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ "Creating Mansfield: The man behind Mid-Ohio Opera". Mansfield News Journal. October 7, 2015. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ "Mid-Ohio Opera to perform Schubert's 'Die Winterreise' May 15". Richland Source. May 3, 2015. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ "Love, sex, violence: Mid-Ohio Opera offers 'Pagliacci'". Mansfield News Journal. August 21, 2014. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Brief History of Mansfield". The Mansfield Savings Bank. rootsweb. 1923. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ "About". Jared Mansfield (1759–1830). Archived from the original on September 12, 2006. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ^ History of Richland Country 1807–1880. Page 237. Compiled by A.A. Graham. Published by A.A. Graham & Co.

- ^ History of Richland Country 1807–1880. Page 272. Compiled by A.A. Graham. Published by A.A. Graham & Co.

- ^ a b "Visitors". Welcome to The City of Mansfield, Ohio. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ^ History of Richland County 1807–1880.Compiled by A.A. Graham. Published by A.A.Graham & Co

- ^ "City of Mansfield, Ohio Comprehensive Annual Financial Report For The Year Ended December 31, 2020" (PDF). City of Mansfield, Ohio. December 31, 2020. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ "Mansfield's Railroads". Mansfield Weekly News. rootsweb. December 22, 1887. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ "Mansfield, Ohio". Ohio History Central. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ a b McKee, Timothy Brian (October 10, 2020). "Ohio Brass Builds a City: 1888-1990". Richland County History. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e McKee, Timothy Brian (September 22, 2020). "The Tire: When the Road Belonged to Mansfield 1912-1979". Richland County History. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- ^ McKee, Timothy Brian (November 16, 2019). "Three Mansfields: Tires, actress, and a state". Richland Source. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- ^ "The Storms of March 23–27, 1913". The Great Flood of 1913, 100 Years Later. Silver Jackets. 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ "Mansfield, Ohio: The Flood of 1913". Prezi. June 21, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ Weingroff, Richard F. (April 7, 2011). "The Lincoln Highway". Highway History. Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ a b "History". Oak Hill Cottage. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ^ a b c d McKee, Timothy Brian (December 3, 2016). "Native Son: Shadow of the Leland Hotel". Richland Source. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ McKee, Timothy Brian (February 14, 2015). "The Mansfield-Leland Hotel". Richland Source. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ a b "Mansfield, Ohio "PR Project-Path to Revitalization" Brownfield Initiative – A National Model" (PDF). financialservices.house.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 11, 2013. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ "About Us". Downtown Mansfield, Inc. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ "Tribute Dinner Held For Mayor Lydia Reid". WMFD TV. November 29, 2007. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ "Donald R. Culliver Mayor, City of Mansfield, Ohio" (PDF). City of Mansfield. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ a b "Fact Finding Report" (PDF). Ohio's State Employment Relations Board. November 18, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ^ "Mansfield, like Massillon, faces 'fiscal emergency'". IndeOnline.com. October 19, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ^ "Mansfield Ohio out of fiscal emergency" (PDF). City of Mansfield, Ohio. July 9, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Mansfield Lahm Regional Airport". AirNav. Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- ^ "Richland County High Point, Ohio". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ "USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map". USDA U.S. Department of Agriculture. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ Stanley A. Changnon and David Changnon. The Pre-Christmas 2004 Snowstorm Disaster in the Ohio Valley. Archived December 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on March 28, 2011.

- ^ a b "Top 10 Records for Mansfield, Ohio" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- ^ "Public Information Statement Spotter Reports". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 21, 2007. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- ^ "Thread Stations Extremes". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 26, 2016.

- ^ "Station: Mansfield LAHM MUNI AP, OH". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for MANSFIELD WSO AP, OH, OH 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 7, 2014.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Mansfield, Ohio Fact Sheet. Archived February 12, 2020, at archive.today United States Census Bureau. Retrieved on January 13, 2007.

- ^ a b c "Data Center Results - Mansfield, Ohio". Modern Language Association. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Mansfield City Council". City of Mansfield. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ "Decision 2023: Falquette, Scott seek to reverse roles on Mansfield City Council". www.richlandsource.com. January 20, 2023. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ "President of Council". City of Mansfield. March 7, 2023. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ "1st Ward". City of Mansfield. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ^ "5th Ward". City of Mansfield. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ^ "2nd Ward". City of Mansfield. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ^ "6th Ward". City of Mansfield. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ^ "3rd Ward". City of Mansfield. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ^ "At Large". City of Mansfield. March 6, 2023. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ "4th Ward". City of Mansfield. December 27, 2023. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ "At Large". City of Mansfield. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ^ "Homepage". Mansfield Division of Police. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- ^ a b "Mansfield, OH Crime Rates". Neighborhood Scout. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "Largest Employers". Richland Community Development Group. Archived from the original on September 8, 2013. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ Ohio History Central Online Encyclopedia. "Tappan Stove Company". Retrieved February 14, 2007.

- ^ a b c d McKee, Timothy Brian (August 11, 2021). "A look back at Westinghouse with a century of history in Mansfield". Richland Source. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- ^ "COMPANY NEWS; AK STEEL ENDS 3-YEAR LOCKOUT OF WORKERS AT OHIO PLANT". The New York Times. December 11, 2002. Retrieved January 16, 2007.

- ^ "Two Ohio cities, Parma and Ontario, react to news from General Motors". Cleveland.com. June 2, 2009. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- ^ "About Ideal Electric Company". Ideal Electric Company. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ^ "About Us". Therm-O-Disc. Archived from the original on September 16, 2012. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- ^ "Company History". The Gorman-Rupp Company. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- ^ "History". The Carousel Works. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- ^ "Home page". StarTek. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- ^ "About Us". School Specialty. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ^ "Commitment and History". Mansfield Engineered Components. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ^ "Leading Employers by all Sectors & Individual Sectors". Welcome to the Richland County Economic Development Corporation. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ "About Mansfield Hospital". OhioHealth. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ^ "About Us". Jones' Potato Chip Company. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ^ "HSF: A Chronology". The Highway Safety Foundation: A Chronology (who list of scare films that were released). Retrieved June 18, 2007.

- ^ "The Shawshank Redemption (1994) – Locations". IMDb.

- ^ Escape Plan: The Extractors/Filming Locations

- ^ "Homepage". Miss Ohio Scholarship Program. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ^ "Home page". Richland County Fair. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- ^ a b "History". Richland County Fair. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ^ "The Ohio State Reformatory". Ancestral Findings. May 13, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ^ "Film and Television". The Ohio State Reformatory. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ^ a b "About the Ohio State Reformatory". The Ohio State Reformatory. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ^ "Tours". The Ohio State Reformatory. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ^ "About Us". The Mansfield Memorial Museum. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ^ "Homepage". Mansfield Art Center. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ^ "About Us". BibleWalk. May 25, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ "Homepage". Welcome to The Haunted Bissman Building. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ^ "Parks and Recreation". Welcome to The City of Mansfield, Ohio. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ^ a b "Map of Mansfield, OH". Yahoo Maps. Retrieved October 17, 2007.

- ^ "Welcome". Richland Carousel Park. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- ^ "Carousels by The Carousel Works". The Carousel Works. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "Louis Bromfield". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on February 10, 2015.

- ^ "The Religious Affiliation of Lauren Bacall: great American actress". Adherents.com. July 30, 2005. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Snow Trails homepage". Snow Trails. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ a b "Richland B&O Bike Trail". Ohio Tourism. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ "About the Renaissance". Renaissance Theatre. July 2, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ "Mid Ohio Civic Opera". www.midohiocivicopera.org. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ "History of the Mansfield Playhouse". Mansfield Playhouse. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ "Mansfield News Journal". Mansfield News Journal. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ Source, Richland. "Independent local news from Mansfield Ohio and surrounding communities in Richland and Crawford Counties. Local news, sports, business, the arts, education, history, and lots more". Richland Source. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ "Mansfield Daily Shield". Library of Congress. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- ^ "WMFD-TV". WMFD.com. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- ^ greatschools. "Mansfield City School District Profile". Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- ^ greatschools. "Madison Local School District Profile". Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- ^ "The Ohio State University Mansfield homepage". The Ohio State University Mansfield. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "North Central State College homepage". North Central State College. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "Homepage". Ashland University – Dwight Schar College of Nursing & Health Sciences. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- ^ "2008-2009 Challenged School Districts". Ohio Department of Education. State of Ohio. Archived from the original on February 7, 2010. Retrieved September 15, 2009.

- ^ Harris, Chriss (January 29, 1989). "Japanese get special school". News-Journal. Mansfield, Ohio. pp. 1-B, 2-B. - Clipping of first and of second page by Newspapers.com.

- ^ "About". Mansfield/Richland County Public Library. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ a b "Why do semi trucks consistently get stuck in Mansfield's subway?". Richland Source. June 7, 2019. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ^ "RCT homepage". Richland County Transit. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ "Mansfield Checker Cab homepage". Mansfield Checker Cab. Archived from the original on September 8, 2010. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ "Mansfield Lahm Regional Airport homepage". Mansfield Lahm Regional Airport. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ "179th Airlift Wing". 179th Airlift Wing, Ohio Air National Guard. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ "Ashland Railway homepage". Ashland Railway. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ "Tearoom :: About". Archived from the original on July 29, 2014. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ^ "The Story of Johnny Appleseed". J Appleseed & Co. Archived from the original on December 31, 2006. Retrieved January 20, 2007.

- ^ "Sister Cities of Mansfield, Ohio, USA". PurposeGames. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ "The Sister Cities Association". Sister Cities Association of Mansfield, England. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

External links

edit- Official website

- Mansfield/Richland County Convention and Visitors Bureau

- Mansfield travel guide from Wikivoyage