54°12′N 23°24′E / 54.2°N 23.4°E

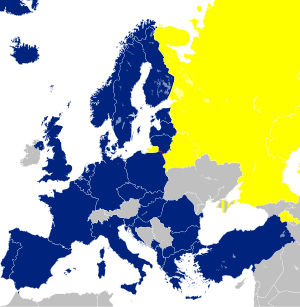

The Suwałki Gap, also known as the Suwałki corridor[a][b] ([suˈvawkʲi] ), is a sparsely populated area around the border between Lithuania and Poland, and centres on the shortest path between Belarus and the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad Oblast on the Polish side of the border. Named after the Polish town of Suwałki, this choke point has become of great strategic and military importance since Poland and the Baltic states joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

The border between Poland and Lithuania in the area of the Suwałki Gap was formed after the Suwałki Agreement of 1920, but it carried little importance in the interwar period as at the time, the Polish lands stretched farther northeast. During the Cold War, Lithuania was part of the Soviet Union and communist Poland was a member of the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact alliance. The dissolution of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact hardened borders that cut through the shortest land route between Kaliningrad (Russian territory isolated from the mainland) and Belarus, Russia's ally.

As the Baltic states and Poland eventually joined NATO, this narrow border stretch between Poland and Lithuania became a vulnerability for the military bloc because, if a hypothetical military conflict were to erupt between Russia and Belarus on one side and NATO on the other, capturing the 65 km (40 mi)-long strip of land between Russia's Kaliningrad Oblast and Belarus would likely jeopardise NATO's attempts to defend the Baltic states, because it would cut off the only land route there. NATO's fears about the Suwałki Gap intensified after 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea and launched the war in Donbas, and further increased after Russia started a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. These worries prompted the alliance to increase its military presence in the area, and an arms race was triggered by these events.

Both Russia and the European Union countries also saw great interest in civilian uses of the gap. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Russia attempted to negotiate an extraterritorial corridor to connect its exclave of Kaliningrad Oblast with Grodno in Belarus. Poland, Lithuania and the EU did not consent. Movement of goods through the gap was disrupted in summer 2022, during the Russian invasion of Ukraine, as Lithuania and the European Union introduced transit restrictions on Russian vehicles as part of their sanctions. The Via Baltica road, a vital link connecting Finland and the Baltic states with the rest of the European Union, passes through the area and, as of April 2024, is under construction. The expressway connection from the Polish side, the new S61 expressway, is almost complete, while the A5 highway in Lithuania is being upgraded to a divided highway. The Rail Baltica route near the Suwałki Gap is still in pre-construction stages.

Background

editThe Suwałki Gap is a sparsely populated region in the north-eastern corner of Poland, in Podlaskie Voivodeship. This hilly area, one of the coldest in Poland,[1] is located on the western margins of the East European Plain. It is crossed by numerous river valleys and deep lakes (such as Hańcza and Wigry), and its vast swathes are covered by thick forests (including the Augustów Primeval Forest) and marshes, such as those in the Biebrza National Park.[2][3] To its west lies another lake district known as Masuria. The area is relatively poorly developed - there is little industry besides forestry-related facilities, the road network is sparse and the nearest large airport is located several hundred kilometres away;[3][4] only two major roads (with at least one lane in each direction) and one rail line link Poland with Lithuania.[5][6] The area is home to some ethnic minorities, particularly Ukrainians, Lithuanians (close to the border with Lithuania) and Russians, but the Russians are not very numerous on the Polish side.[2][7]

Poland and Lithuania both gained independence in the aftermath of World War I and started to fight in order to establish control over as much terrain as they could militarily hold. While Lithuania claimed majority-Polish Suwałki and Vilnius, it ultimately failed to control both. Suwałki was agreed to be part of Poland as a result of the Suwałki Agreement, while Vilnius was captured by Poland in a false flag operation known as Żeligowski's mutiny.[8] In the interwar period, the Suwałki region was a protrusion of Poland into surrounding Lithuania and East Prussia (part of Germany), rather than a gap, and played little strategic importance.[3]

Following World War II, the vicinity of Königsberg, renamed Kaliningrad shortly after the war, was incorporated as part of the Russian SFSR, part of the Soviet Union, and became a closed area for most of the Soviet era.[9] Lithuania became a Union republic within the USSR, while Poland came under the Soviet sphere of influence and joined the Warsaw Pact. Until the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Poland's only eastern and northern neighbour was the USSR, thus, as in the interwar period, the region mattered little in military terms.[5][10] This changed after 1991, when Kaliningrad Oblast became a semi-exclave of Russia, sandwiched between Poland and Lithuania, both of which are neighbours with Belarus. Neither borders the "mainland" part of Russia.[6]

Kaliningrad Oblast's neighbours both entered the European Union and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). At the same time, only 65 km (40 mi) of Polish territory separates two areas of the rival Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) and the Union State, both of which include Russia and Belarus.[6] The former Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves claims to have come up with the name "Suwałki Gap" before his meeting with Ursula von der Leyen, then serving as the defence minister of Germany, in April 2015 to highlight the vulnerability of the area for the Baltic states.[11]

Civilian interests

editRussian corridor

editThe first time a special corridor between Kaliningrad and Belarus (planned to go via Poland) was discussed was during a 1990 meeting between Yuri Shemonov, a senior official in Kaliningrad Oblast, and Nikolai Ryzhkov and Mikhail Gorbachev, Premier and President of the Soviet Union, respectively. While Ryzhkov was supportive of the idea, Gorbachev vetoed the proposal, urging the other two men to "stop spreading panic".[12]

After the Soviet Union fell apart, Kaliningrad was cut off from Russia, thus the Russians sought to secure a land transit route from the exclave to mainland Russia through Belarus. After some initial preparations, including signing a treaty which obliged Poland and Russia to open a border crossing near Gołdap, the Russian government announced their intention to build a special "communication corridor" between the checkpoint and Grodno in Belarus, justifying the decision by the region's close economic ties with the country. Russia, which communicated the idea to the Polish side in 1994, additionally sought to bypass Lithuania, with which it had strained diplomatic relations.[13] Initially, the idea sparked little interest,[13] but extensive discussions came in 1996, when Boris Yeltsin, President of Russia, declared he would negotiate with the Polish side to seek permission to build a motorway, citing high transit costs via Lithuania.[14]

Top Polish government officials rejected the proposal.[15] Among the main reasons was the fact that among Poles, the proposal sounded too much like the German request for an extraterritorial link through the Polish Corridor just prior to its 1939 invasion of Poland, and was thus seen as unacceptable.[16][17] This feeling was amplified by the persistent usage of the word "corridor" among Russian officials.[18][19] Aleksander Kwaśniewski, then-president of Poland, sounded concerns about the environmental impact of the investment,[14] while some politicians from the then-ruling coalition (SLD-PSL) argued that the corridor would cause a deterioration of diplomatic relations between Poland and Lithuania.[13][20]

There have been reports that Suwałki Voivodeship started talks about the corridor to alleviate its economic problems and even signed an agreement with Grodno Region authorities to promote its construction via a border crossing in Lipszczany,[12][20] but Cezary Cieślukowski, then-voivode of Suwałki who was seen by the media as supportive of the idea, denied having ever endorsed the proposal, and no proof for that (such as plans or cost estimates) was found in an internal party investigation.[13] When GDDKiA, the Polish agency responsible for the maintenance of main roads, updated its plans for the expressway network in 1996, the proposed link was nowhere to be found.[21]

The topic returned in 2001–2002 when Poland and Lithuania were negotiating accession to the European Union. Russian citizens in Kaliningrad were facing the prospect of having to use passports and apply for visas to cross the border of the new EU member states, which sparked outrage in the Russian press. Therefore, Russia suggested that the European Commission grant a right to a 12-hour free transit for the citizens of the oblast through special corridors in Poland and Lithuania, but this proposal was rejected.[22] Another proposal, with sealed trains, also failed to gain traction; it was ultimately agreed to introduce special permits for Russian citizens travelling to/from Kaliningrad Oblast for transit through Lithuania (but not Poland),[19] known as Facilitated Rail Transit Document (FRTD) and a Facilitated Transit Document (FTD) for rail and road trips, respectively.[23]

Kaliningrad Oblast has since been generally supplied by freight trains transiting through Lithuania. However, on 17 June 2022, in retaliation for Russia's invasion of Ukraine, Lithuania started blocking supplies of sanctioned items to the enclave via road or rail, citing EU's sanction guidance.[24] That guidance was then clarified in a way that exempted rail traffic from the restrictions so long as the volume of deliveries remained within prior consumption volumes,[25] but then Šiaulių bankas, the bank servicing the transit payments, announced it would refuse to accept ruble payments from 15 August and any payments from Russian entities from 1 September.[26]

Transit remains possible via payments to other banks but, in September 2022, was expected to become more burdensome as payments for each freight service will be processed separately to comply with Lithuanian anti-fraud regulator's guidance.[27] Another possibility remains for ships to go from St. Petersburg to Kaliningrad, but this route may be unavailable in winter because the more northerly port may freeze.[28]

EU economic infrastructure

editThe Suwałki Gap hosts several critical corridors because it is the only land route between the Baltic states and the rest of the European Union and NATO.

A strategic communication artery, known in the international E-road network as E67 or as Via Baltica (expressway S61 on the Polish side and A5 highway on the Lithuanian part), passes through the Suwałki Gap.[29] It is part of the North Sea-Baltic Corridor (previously the Baltic-Adriatic Corridor),[30] one of the core routes of the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) that connects Finland and the Baltic states with the rest of Europe.[31] As of April 2024, the Polish expressway is almost completed; the only segment not yet open is the bypass of Łomża, expected to be unveiled in May 2025.[32][33][34] On the Lithuanian side, the existing A5 highway is being upgraded to a dual highway with grade-separated junctions. The section of the motorway close to the Suwałki Gap is slated to be completed by late 2025.[35]

The Rail Baltica project, currently under construction, will improve the existing connection between the Baltic states and the rest of the European Union by creating a new, unified standard-gauge trunk line running across the Baltic states from Kaunas to Tallinn and eventually underneath the Gulf of Finland to Helsinki. The existing rail connection is only a single-track, non-electrified line that can only go to Kaunas without changing track gauges. This is because Baltic state railways still use the wider Russian gauge, while the vast majority of Polish rolling stock is adapted to the standard gauge common in Western Europe.[36] The Polish sections are expected to be ready by 2028, but as of February 2024 construction work in Poland is already delayed by 3 years and there is no guaranteed funding for the section between Ełk and the Polish-Lithuanian border.[37]

The Gas Interconnection Poland–Lithuania, which opened on 1 May 2022, is the only terrestrial link between the Baltic and Finnish natural gas pipeline system and the rest of the European Union. Its strategic importance was the reason it was recognized as a Project of Common Interest by the EU.[38] The LitPol Link is the route for the only land-based high voltage line between Poland and Lithuania, which was opened in late 2015.[39] Another high-voltage line to Lithuania is yet in the planning stages, as the sea-based Harmony Link (through Klaipėda) was found to be economically unfeasible.[40]

The Suwałki Gap is an important constraint on civilian airspace since the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine began. Because of sanctions against Russia and Belarus (in the latter case imposed after Roman Protasevich's airplane was hijacked by the government while over its airspace), aviation from these countries may not fly through the European Union, including to Kaliningrad. However, Russia also banned EU carriers over its territory, and EU airlines were urged not to fly over Belarus.[41][42] Thus the only feasible way for civilian planes to fly from the Baltic states or Finland southwards is through the Suwałki Gap, or over the Baltic Sea.

- Civilian infrastructure crossing the Suwałki Gap

-

The E67 route, gradually upgraded to expressway standards

-

Progress on expressway S61 in Poland, leading to the Suwałki Gap, as of April 2024. Green: open. Red: under construction

-

The planned Rail Baltica route

-

LitPol Link, the high-voltage electricity line connecting Poland and Lithuania

Military considerations

editHistory

editLong before the Suwałki Gap became of concern to NATO, several army battles or operations occurred on the terrain. For example, during Napoleon's war in Russia, part of his army, which crossed into the country from the Duchy of Warsaw, used the Suwałki Gap as a launching pad for the invasion and, by the beginning of 1813, when the remnants of his army retreated, it crossed the gap from Kaunas towards Warsaw. Both battles of the Masurian Lakes during World War I passed or were directly waged on the territory. During the invasion of Poland, which started World War II, most of the action skirted the area, while in 1944, the Red Army simply advanced into East Prussia and no major battle occurred in the area.[6]

Poland and Lithuania joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in 1999 and 2004, respectively. On the one hand, this meant that the Kaliningrad exclave was surrounded by NATO states, but on the other, this created a choke point for the military alliance as all troops supplied by land must pass through the Suwałki Gap. In the event of its capture, the Baltic states would be surrounded by Russia, Russian-controlled territories, and Belarus, a Russian ally.[43]

Even if Belarus or Russia are not physically present in the corridor, it is narrow enough for the short-range rockets stationed in either country to target any military supplies coming through the corridor, while alternative routes of delivery, i.e. by sea or air, are also threatened by the anti-air and anti-ship missiles stationed in Kaliningrad Oblast.[44][45] Due to its strategic importance for NATO and the Baltic states, it has been described as one of NATO's hot spots,[2] its "Achilles' heel"[46] and dubbed the modern version of the Fulda Gap.[47][48][49][50]

Initially, this vulnerability was of relatively little concern as, throughout most of the 1990s, Russia was stuck in a deep depression, which necessitated large-scale cuts to the country's military budget.[17] Even though the army was of significant size, it was poorly equipped and had low military capabilities.[51] Russia–NATO relations were more cordial then, as Russia was not openly hostile to NATO, which was affirmed while signing the 1997 Founding Act, and it was thought that Russia would eventually become a pacifist democracy, decreasing its military and nuclear presence.[52][c] NATO's commitment not to build any permanent bases beyond the Oder river therefore seemed reasonable.[47]

Escalation of tensions

editThe qualitative and quantitative improvement in armaments started with the rule of Vladimir Putin.[51] Short-range (500 km [310 mi]) Iskander missiles, capable of carrying nuclear warheads, were installed in 2018.[54][55] Additional installations were deployed in the late 2010s, including more area denial weapons, such as K-300P Bastion-P and P-800 Oniks anti-ship missiles and S-400 anti-air missiles.[56][57][45]

In general, the importance of the corridor among the Western nations is said to have been initially underestimated due to the fact that Western countries sought to normalise relations with Russia.[6] Most of NATO's activities therefore concentrated on drills and exercises rather than deterrence.[58] The shift in policy occurred gradually after Russia's aggression in Ukraine, which started in 2014.[44][59][60] After the 2014 Wales summit and then the 2016 Warsaw summit, NATO members agreed on more military presence in the eastern member states of the Alliance, which came to fruition as the NATO Enhanced Forward Presence.[61][62] In 2018, the Polish side proposed to station a permanent armoured division in the Bydgoszcz-Toruń area (dubbed "Fort Trump") with up to US$2 billion in financial support,[60] but NATO did not agree to it as it was afraid it would potentially run afoul of the 1997 Founding Act, which, among other things, constrains NATO's ability to build permanent bases next to the Suwałki Gap.[63][64]

While the permanent military base ultimately did not appear, the military situation around the region has been steadily escalating, and deterrence tactics seem only to have increased the concentration of firepower on both sides.[7] Several military drills, including Zapad 2017, Zapad 2021 and the Union Resolve 2022 exercises in Belarus and Kaliningrad Oblast and others that were unexpected,[7] and NATO's 2017 Iron Wolf exercises in Lithuania as well as some of the annual Operation Saber Strike operations,[65] occurred in areas close to the Suwałki Gap. Around 20,000 soldiers riding 3,500 military vehicles participated in the Dragon 24 NATO drill in Northern Poland.[66]

The Russian forces did not leave Belarus after the 2022 exercises and invaded Ukraine from the north in February and March that year. As the war on NATO's eastern border unraveled, NATO dispatched more troops to its eastern flank,[67][68] though its representatives said it would not establish permanent presence on its eastern borders.[69] The situation around the area further intensified following Lithuania's declaration on banning the transit of sanctioned goods through its territory.[70] As the security situation rapidly worsened on the east, the Lithuanian and Icelandic ministers of foreign affairs said that Russia had effectively repudiated the 1997 agreement,[71] which was also indirectly suggested by Mircea Geoană, NATO's Deputy Secretary General.[72]

However, by the end of 2023, several assessments found that the threat has become much smaller after the invasion began. They suggested that Russian troops getting bogged down in eastern and southern Ukraine, accession of Sweden and Finland to NATO and a change in the alliance's tactics that saw more troops deployed on NATO's borders meant that Russia was much less likely to start another war.[28][73]

Current standing of forces

editNATO and its member states

editAs of spring 2022, units closest to the Suwałki Gap that belong to NATO or to its member states included:

- 900 German soldiers[74] together with Czech, Norwegian and Dutch troops, totalling about 1,600 personnel, alongside the Mechanised Infantry Brigade Iron Wolf, dispatched in a NATO multinational division in Rukla on the Lithuanian side, 140 km (87 mi) from the border.[75] The brigade is armed with Leopard 2 tanks, Marder infantry fighting vehicles, and PzH-2000 self-propelled howitzers.[76] In June 2023, Defence Minister Boris Pistorius announced that the Germans would increase their presence to 4,000 troops, but the whole brigade is only expected to come in 2027.[77] A €300 million project is going to expand the premises of the military base.[78] A subunit of the Iron Wolf brigade, the Grand Duchess Birutė Mechanized Uhlan Battalion, is stationed in Alytus, 60 km (37 mi) from the Polish-Lithuanian border. Additionally, the military base in Rūdninkai Training Area, which is 35 km (22 mi) south of Vilnius and about 125 km (78 mi) from the Suwałki Gap, was ordered to be reactivated as a matter of urgency after the Seimas passed a bill to that effect.[79] The base was reopened in June 2022 and is capable of holding 3,000 soldiers.[80]

- An American battalion-sized group, 800 people, from the 185th Infantry Regiment, as of mid-2022, together with the Polish 15th Mechanised Brigade, as well as 400 British Royal Dragoons and some Romanian and Croatian troops. These troops are stationed near the Polish towns of Orzysz and Bemowo Piskie, about the same distance from the border as Rukla.[81][82] The forces are armed with American M1 Abrams and Polish modified T-72 tanks, Stryker, M3 Bradley and Polish BWP-1 infantry fighting vehicles, Croatian M-92 rockets and Romanian air defence systems.[36][76] Brigades in both countries operate on a rotational basis. The Polish and Lithuanian host brigades signed an agreement for mutual cooperation in 2020, but, unlike with the operations with foreign forces, these are not subordinate to NATO command;[83][84]

- The 14th Anti-Tank Artillery Regiment, under Polish command, garrisoned in Suwałki and armed with Israeli Spike-LR missiles. The regiment was briefly degraded to a squadron as its equipment was outdated.[36] Some other forces in the area under Polish command include an artillery regiment in Węgorzewo, a mechanised brigade in Giżycko and an anti-air unit in Gołdap.[46]

- Up to 40,000 troops within NATO Response Force, activated on 25 February 2022 following Russia's invasion in Ukraine, which are available on short notice.[85]

In June 2022, Jens Stoltenberg, Secretary General of NATO, pledged more weapons and troops to the Baltic States, seeking to augment NATO's presence to a brigade in each of the Baltic states and Poland (3,000-5,000 troops in each country), while the NATO Response Force will be increased to 300,000 troops.[86]

Russia and Belarus

editKaliningrad Oblast is a very heavily militarized area subordinate to the command of the Western Military District.[87] Until the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Western MD hosted the best equipment and army forces at Russian disposal.[88] In 1997–2010, the whole oblast was organised as a special region under a unified command of all forces dispatched there. Kaliningrad is the headquarters of the Baltic Fleet and the headquarters of the 11th Army Corps (Russian Navy), which has ample air defence capabilities and whose divisions have undergone extensive modernisation in the late 2010s.[89]

According to Konrad Muzyka, who authored a detailed study on the district's forces, the units stationed in Kaliningrad permit medium-intensity combat in the area without support from the Russian mainland. The town of Gusev, in the eastern part of the oblast, just 50 km (31 mi) from the Vištytis tripoint, hosts the 79th Motor Rifle Brigade (BMP-2s and 2S19 Msta self-propelled howitzers) and the 11th Tank Regiment (90 tanks, of which most are T-72B1s at least 23 are the more recent T-72B3s).[90][91]

Missile units are stationed on the Chernyakhovsk air base (Iskander missile launchers), while the majority of air defence units (Smerch and BM-27 Uragan multiple rocket launchers) are located in the vicinity of Kaliningrad.[88] Kaliningrad also hosts capabilities to conduct electronic warfare,[88] in which the Russian forces have both inherited much experience from the Soviet times and earned it during hybrid warfare operations such as in Donbas.[92]

Russia has not officially confirmed whether it has nuclear warheads in the exclave, but Iskander missiles are known to be capable of carrying such weapons.[93] In 2018, the Federation of American Scientists published photos showing a weapons storage facility northwest of Kaliningrad being upgraded in a way that enables nuclear weapons storage.[94] In addition to that, Arvydas Anušauskas, the Lithuanian minister of defence, claimed that Russia already has these in the exclave.[95][96]

Belarus's military command, while formally independent as a military command of a sovereign state, has organisationally aligned itself with the Russian command and is in many respects wholly or substantially dependent on Russian defence institutions and contractors, while persistent underinvestment in its own military and deepening ties with its eastern neighbour left the military with low offensive capabilities, with the only feasible role being that of support of the main Russian forces.[97][98] For instance, the countries share the air defence system, including its command.[99]

There are relatively few units on the Belarusian side - the headquarters of the Western Operational Command (one of the two in Belarus) as well as the 6th Mechanised Brigade is in Grodno (S-300 anti-air missiles),[100] while air operations may be conducted from the military air base in Lida.[98] They have received some Russian reinforcements ahead of Zapad-2021 exercises, including more S-300 missiles in Grodno,[101] and in early 2022, when S-400 missiles were installed in Gomel Region. In May 2022, Alexander Lukashenko announced that he had bought Iskanders and S-400 missiles from the Russians.[102]

Strategy

editAttack

editThere is broad consensus among Western military think tanks that any hypothetical attack on NATO would involve an attempt to capture the Suwałki Gap and therefore to surround the Baltic states.[60] The reasons for the hypothetical attack are seen not to be primarily the occupation of the three former Soviet republics by Russia but to sow distrust in NATO's capabilities, to discredit the military alliance and to assert Russia's position as one of the major military powers.[7][60] A possible scenario for such a move was voiced by Igor Korotchenko, a retired Russian colonel and state TV pundit, who suggested that the Russians could take over the Suwałki Gap as well as the Swedish island of Gotland while jamming NATO's radio signals, in order to establish effective military control over all possible supply routes to the Baltic states.[103] Another summary was presented by Franz-Stefan Gady of the International Institute for Strategic Studies, where he suggested that Russia would capture the Suwałki Gap and then force NATO to back down using the threat of deploying nuclear weapons.[77]

Despite being shorter, the Polish side of the Suwałki Gap is unlikely to be used as the area of main concentration of these forces, according to these experts. A 2019 Russian paper indicated that the potential attack cutting off the Baltic states from NATO could be held north of the Suwałki Gap, in south-western Lithuania, due to better efficiencies for the Russian forces;[104][105] the same route was assumed in Zapad 2017[3][88] and Zapad 2021[106] military exercises. This is also an area of attack deemed more favourable by the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA)[6] and the Swedish Defence Research Agency (FOI)[107] papers, as the terrain is flatter and less forested and thus easier for heavier troops. Faustyna Klocek was one of the few proposing that the attack would lie over Polish territory.[108]

Some analysts suggest another theory, namely that the importance of the Suwałki Gap is overblown. CNA's Michael Kofman compared the Suwałki Gap's to a "MacGuffin" (by itself unimportant but what he argues could be part of a frontline stretching for hundreds of kilometres) and arguing that previous analyses, which were necessarily limited, relied on a simplified view of the Russian military and did not sufficiently analyse its doctrine as a whole.[109] Franz-Stefan Gady, on the other hand, opined that if Russia's goal were to present a fait accompli situation, it would be easier for Russia to capture any Baltic state rather than specifically the Suwałki Gap because the Russians would have to defend it against Poles and possibly Germans instead of the small armies of the Baltic states.[77] Alexander Lanoszka of Chatham House says that Russia has no interest in closing the gap, as the transit agreements are already good enough and invading NATO would create as many problems for Russia as NATO would have.[110] Fredrik Westerlund (FOI) had a similar point of view.[89]

During the migrant crisis on the eastern border of NATO and EU, there were concerns voiced by NATO and Ukrainian intelligence officials that Belarus would send migrants to the Suwałki Gap in order to destabilise the area, which in turn would give a pretext for Russia to introduce "peacekeeping" troops.[111] The Polish government's fear that Russia could potentially open up a migrant route via Kaliningrad Oblast culminated in a decision to build a fence on the border with the exclave, similar to the one Poland erected on the Belarusian border the previous year.[112] To some extent, these fears were justified after the Wagner Group aborted the rebellion in Russia and was thus exiled to Belarus. The mercenaries started training Belarusian soldiers in close proximity to the Polish border near the vulnerable area, which prompted the Polish Armed Forces to close some of the border crossings and send 10,000 reinforcement troops.[28]

Some of the initial assessments were grim about the prospect of the Baltic states. In 2016, the RAND Corporation ran simulations that suggested that with the NATO forces available at the time and despite less military presence in the area than in the Soviet times, an unexpected attack would have Russian troops enter or approach Riga and Tallinn in 36–60 hours from the moment of the invasion. The think tank attributed the swift advance to the tactical advantage in the region, easier logistics for Russian troops, better maneuverability and an advantage in heavy equipment on Russia's side.[113][114] In general, the Russian Armed Forces, according to NATO's expectations, will try to overwhelm the Baltic states, cut off its only land route to the rest of NATO and force a fait accompli situation before the Alliance's reinforcements are able to come by land (air reinforcements are much more expensive and are vulnerable to surface-to-air strikes), only to face a dilemma between surrendering the area to the invader and directly confronting Russian troops, potentially escalating the war to a nuclear conflict.[107]

Ben Hodges, a retired US Army general who served as a high-ranking NATO commander and who co-authored a paper published by the CEPA[6] on the defence of the Suwałki Gap, said in 2018 that the Suwałki Gap was an area where "many (of) NATO's [...] weaknesses converge[d]". Following major setbacks in the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Hodges revised his opinion towards a more positive tone, saying that NATO was much better prepared and could hold control over the area in case of an attack, particularly since Sweden and Finland would, in his opinion, likely help NATO despite at the time not being members of the alliance.[5] An Estonian MP estimated that Finland's membership in NATO, for which the accession protocol was signed in 2022, would make the security situation of the Baltic states more tenable thanks to an alternative corridor lying through the waters of the Gulf of Finland, which could be enforced using the relatively robust Finnish Navy.[115] It was also suggested that Swedish accession to NATO would finally grant NATO some strategic depth in the area and otherwise facilitate the defence of the Baltic states.[116][117]

There appears to be strong support for Russia's invasion of the area among the Russians. A March 2022 survey by a Ukrainian pollster, which was concealing its identity while soliciting answers and which was asking questions using the Russian government-preferred rhetoric, reported that a large majority of Russians could support an invasion of another country should the "special military operation", as Russia officially calls the invasion of Ukraine, succeed, and that the most support for that invasion (three-quarters of those who did not abstain from an answer, and almost half of all respondents) would be against Poland, followed by the Baltic states.[118][119]

Defence

editWhile the Suwałki Gap is a choke point, military analysts suggest that the fact that the region has abundant thick forests, streams and lakes means that the landscape facilitates defence against an invading force.[2][3][46] Additionally, the soil in the area makes it very hard to operate under rainy conditions as off-road areas or roads without a hard surface become impassable mud.[2] The Center for European Policy Analysis paper points out that the hilly and more forested terrain of the Polish part of the Suwałki Gap favours actions on the defensive side, such as ambushes and holding entrenched positions;[6] at the same time, low density of roads that are largely not designed for carrying heavy cargo means that the few that remain available for the military may be easily blocked.[46]

The natural defences largely eliminate the need for additional military fortifications, and some of them, such as the one in Bakałarzewo, have been converted to private museums.[46] On the other hand, this also means that once Russia is in possession of the corridor, which could happen if NATO reinforcements arrive late, it will be very hard to eject the Russians from the area.[120] These reports say that the conditions are unfavourable for heavy equipment, particularly in bad weather, though John R. Deni of the Strategic Studies Institute argued the terrain was generally fine for a tank offensive.[121]

The current Polish military doctrine under Mariusz Błaszczak, the Polish Minister of Defence (MoD), is to concentrate the units close to the Russian and Belarusian borders in order to wage a defensive campaign in a similar way to the one Poland was conducting in September 1939.[122] There were two war games made to verify the scenario. In the first one, made in 2019, the US Marine Corps War College modelled a hypothetical scenario of World War III.[123] The other one, codenamed Zima-20, was conducted by the Polish War Studies Academy on MoD's request in 2020. Most of its assumptions remain confidential,[124] but it is known that they include units with yet-to-be-delivered upgraded equipment that try to endure 22 days of defence against an invading force and, similarly to the American model, the military activities start in the Suwałki Gap and Poland tries to defend Eastern Poland at all cost.[125]

Both results were catastrophic: in the American simulation, Polish units would incur about 60,000 casualties in the first day of war, and NATO and Russia would fare a battle that would prove very bloody to both sides, losing about half of the participating forces within 72 hours.[123] Zima-20's results, which are interpreted with some dose of caution, showed that by day 4 of the invasion, the Russians already advanced to the Vistula river and fighting in Warsaw was underway, while by day 5, the Polish ports were rendered unusable for reinforcements or occupied, the Navy and the Air Force were obliterated despite NATO's assistance,[124] while the Polish units dispatched close to the border could lose as much as 60-80% of personnel and materiel.[126][d]

Very few locals are expected to endorse an invasion, in contrast to what happened in Crimea in 2014, as the influence of the Russians in the area is not significant;[7] that said, Daniel Michalski's survey found that the region's local population is inadequately prepared for a hypothetical military conflict and that the area has next to no civilians immediately ready to engage in combat.[128] Regional tensions are such that some tourists are afraid to go there, though Andrzej Sęk and retired Col. Kazimierz Kuczyński say that such fears are likely unfounded as Russia's resources are being expended in Ukraine.[129] Additionally, the Russians may want to use the historic tensions between Poland and Lithuania to set them against each other.[113]

Proposed solutions

editNATO's military doctrine assumes that its member states would have to hold the invasion for as long as NATO needs to send reinforcements to the attacked states, and in the meantime, NATO would operate on the terrain using tripwire forces dispatched in the area.[6] There is no consensus about the right kind of forces and their mode of deployment near the Suwałki Gap that would best fit the doctrine, though the predominant thought goes that at least some forces or money to improve infrastructure should be sent to Poland.[60]

Among the analysts that took into account the Suwałki Gap vulnerability in their reports or opinion pieces, the majority argued that some form of permanent U.S. military presence in Poland should exist, and most of the reports agreed that the NATO (or American) units should be as mobile as practically possible.[130] The Warsaw Institute argued that while it would be costly to maintain, the military base proposed by Poland in 2018 would be an effective deterrent for Russia and would ensure quick dispatches of U.S. forces to the Suwałki Gap if needed.[131]

Hunzeker and Lanoszka say that fears over the bottleneck are exaggerated, as are fears over Russian war against NATO, and they conclude that nothing should constrain the Alliance from attacking Kaliningrad Oblast or Belarus if the latter engages in the conflict, too.[132] They advocate for a permanent presence of U.S. military but with units dispersed all over Poland instead of one big military base, and crafted in a way that avoids as much Russian rebuke as possible.[133] Lanoszka separately suggests troops dispatched to Russian-minority areas in Estonia and Latvia instead, as he believes Russia is more likely to make a limited incursion on these areas.[110] Another report, by the Strategic Studies Institute (SSI), also suggested a permanent presence of one brigade of NATO troops in each of the Baltic states.[134]

Hodges et al., writing for CEPA, in principle supported an increased permanent presence of U.S. forces (including a divisional headquarters) but also said that NATO forces must be more mobile so that Russian troops have no chance to avoid the tripwire units. The report also recommended that more effort should be put into improving transport capabilities and reducing red tape between NATO's member states, noting that defending the Suwałki Gap is a much different challenge from that of the Cold War-era Fulda Gap.[6] John R. Deni of the SSI echoed CEPA paper's arguments and argued that since Russia deployed a large contingent of Russian troops together with modern arms in Belarus just prior to the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, NATO should disregard the 1997 Founding Act and start a dramatic increase of armaments and troop numbers near the Suwałki Gap and in the Baltic states.[121]

Some experts argued the opposite, i.e. that increased NATO presence may be detrimental for NATO. Nikolai Sokov of the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, writing for the conservative outlet The National Interest, criticised the recommendations for ramping up military presence, arguing that Russia and NATO should learn to live with their own vulnerabilities in order to prevent an arms race.[135] Some people, including Dmitri Trenin of Carnegie Moscow Center, said this had already been happening due to NATO's increased presence in the area.[136]

James J. Coyle of the Atlantic Council similarly argued that the West should not escalate by sending more troops to the immediate vicinity of the Suwałki Gap, but instead rely on efficient logistics in case of war.[137] Viljar Veebel and Zdzisław Śliwa, on the other hand, proposed that NATO should either deploy as many troops as it can while not paying attention to Russia's complaints about that or attempt to convince them (by escalating elsewhere, for example) not to reinforce their troops near the Suwałki Gap using means other than deterrence.[7]

See also

editOther NATO vulnerabilities:

Explanatory notes

edit- ^ The term "Suwałki corridor" (korytarz suwalski) may refer both to the Suwałki Gap and the road link between Kaliningrad Oblast and (Russian ally) Belarus that was proposed by Russians in the 1990s

- ^ Also known in other languages as: Polish: przesmyk suwalski or korytarz suwalski; Lithuanian: Suvalkų koridorius or Suvalkų tarpas; Belarusian: сувалкскі калідор, romanized: suvalkskі kalidor and Russian: сувалкский коридор, romanized: suvalkskiy koridor

- ^ The Founding Act is not a ratified treaty and therefore is not legally binding.[53]

- ^ The government officials initially did not comment on the revelations of the secret war game, though Błaszczak later denied that the exercises were unsuccessful and said that the Polish Armed Forces were capable of withholding a potential offensive.[127]

References

edit- ^ Zubek, Adam (14 August 2011). "Suwalski biegun zimna. Dlaczego tam?" [Cold Pole in Suwałki. Why there?]. Polityka (in Polish). Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Elak, Leszek; Śliwa, Zdzisław (2016). "The Suwalki Gap : NATO's fragile hot spot". Zeszyty Naukowe AON (in Polish). 2 (103). Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Parafianowicz, Ryszard (2017). "The military-geographical significance of the Suwałki Gap". Security and Defence Quarterly. 17 (4): 3–20. doi:10.5604/01.3001.0011.7839. ISSN 2300-8741. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Deni, John R. "NATO Must Prepare to Defend Its Weakest Point—the Suwalki Corridor". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Pita, Antonio (27 March 2022). "El talón de Aquiles de la seguridad europea: un estrecho corredor polaco que discurre junto a Rusia" [The Achilles heel of European security: a narrow Polish corridor that runs alongside Russia]. El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hodges, Ben; Bugajski, Janusz; Doran, Peter B. (July 2018). Securing the Suwałki Corridor: Strategy, Statecraft, Deterrence, and Defense (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f Veebel, Viljar; Sliwa, Zdzislaw (21 August 2019). "The Suwalki Gap, Kaliningrad and Russia's Baltic Ambitions". Scandinavian Journal of Military Studies. 2 (1): 111–121. doi:10.31374/sjms.21. ISSN 2596-3856. S2CID 202304141.

- ^ "NATO's Vulnerable Link in Europe: Poland's Suwalki Gap". Atlantic Council. 9 February 2016. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ "Kaliningrad profile - Overview". BBC News. 12 March 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Münchau, Wolfgang. "Mind the gap". Euro Intelligence. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Karnitschnig, Matthew (16 June 2022). "The Most Dangerous Place on Earth" (PDF). Politico. pp. 18–19. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ a b Maszkiewicz, Mariusz (2016). "The Suwalki Corridor". New Eastern Europe. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2725061. SSRN 2725061. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d Jaśkowska, Zuzanna (27 June 2014). "Kwestia "korytarza suwalskiego" w świetle materiałów z polskiej prasy: lata 90. XX wieku" [The issue of the "Suwałki Corridor" in the light of materials from the Polish press: the 1990s]. historia.org.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ a b Wielka historia świata: Polska. Pontyfikat Jana Pawła II - Rząd Donalda Tuska - Kultura i sztuka II połowy XX w. [The great history of the world: Poland. John Paul II's pontificate - Donald Tusk's government - Culture and art of the second half of the 20th century] (in Polish). Vol. 37. Warsaw: Oxford. 2008. p. 88. ISBN 978-83-7425-025-2. OCLC 751071516. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Bugajski, Janusz (2004). Cold Peace: Russia's New Imperialism. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-275-98362-8. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ Prizel, Ilya; Dunlop, John B. (13 August 1998). National Identity and Foreign Policy: Nationalism and Leadership in Poland, Russia and Ukraine. Cambridge University Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-521-57697-0. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ a b Sakson, Andrzej (1 January 2014). "Obwód Kaliningradzki a bezpieczeństwo Polski" [Kaliningrad Oblast and the security of Poland]. Przegląd Strategiczny (in Polish) (7): 109–121. doi:10.14746/ps.2014.1.8. ISSN 2084-6991. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "Kaliningrad jak Alaska?" [Kaliningrad like Alaska?]. Przegląd (tygodnik) (in Polish). 27 May 2002. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ a b Jaśkowska-Józefiak, Zuzanna (10 January 2017). "Kwestia "korytarza suwalskiego" w świetle materiałów z polskiej prasy: lata 2001-2002" [The issue of the "Suwałki Corridor" in the light of materials from the Polish press: 2001-2002]. Przegląd Archiwalno-Historyczny (in Polish). 2017 (Tom IV): 127–139. doi:10.4467/2391-890XPAH.17.007.14910. ISSN 2720-4774. S2CID 245927778. Archived from the original on 9 February 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ a b Klimiuk, Klaus (9 April 2008). "The Controversial Kaliningrad Corridor". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ "Rozporządzenie Rady Ministrów z dnia 23 stycznia 1996 r. w sprawie ustalenia sieci autostrad i dróg ekspresowych" [Regulation of the Council of Ministers of 23 January 1996 on establishing the network of motorways and expressways.]. isap.sejm.gov.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Kurczab-Redlich, Krystyna (29 June 2002). "Z Rosji do Rosji" [From Russia to Russia]. Polityka (in Polish). Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "Uproshchonnyye tranzitnyye dokumenty" Упрощённые транзитные документы [Simplified transit documents]. General Consulate of the Republic of Lithuania in Kaliningrad (in Russian). 25 March 2022. Archived from the original on 24 April 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ Sytas, Andrius (13 July 2022). "Lithuania will allow sanctioned Russian goods trade to Kaliningrad". Reuters. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ Brzozowski, Alexandra; Peseckyte, Giedre (14 July 2022). "Lithuania won't challenge Brussels over Kaliningrad to avoid 'victory' for Russia". www.euractiv.com. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ "Kaliningrad odcięty od importu. Litewski bank kończy obsługę" [Kaliningrad cut off from imports. A Lithuanian bank ends its service]. Rzeczpospolita (in Polish). Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ "Payments for Kaliningrad rail transit still possible but more complex". RailFreight.com. September 2022. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ a b c "Suwalki Gap: NATO's Eastern European 'Weak Spot' Against Russia". Wall Street Journal. 18 August 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Koziarski, Stanisław M. (2018). "Kierunki rozwoju sieci autostrad i dróg ekspresowych w Polsce" [Directions of development of the network of motorways and expressways in Poland]. Prace Komisji Geografii Komunikacji PTG (in Polish). 21 (2): 7–30. doi:10.4467/2543859XPKG.18.012.10137. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "Part I: List of pre-identified projects on the core network in the field of transport" (PDF). European Commission. October 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "TENtec Interactive Map Viewer". Mobility and Transport: European Commission. Archived from the original on 4 April 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "S61 Łomża Zachód - Kolno". Generalna Dyrekcja Dróg Krajowych i Autostrad - Government of Poland (in Polish). Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ "Mapa autostrad i dróg ekspresowych w Polsce" [Map of highways and expressways in Poland] (in Polish). Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "Mapa Stanu Budowy Dróg" [Road Construction Map]. Generalna Dyrekcja Dróg Krajowych i Autostrad - Government of Poland (in Polish). Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "Lithuania: Via Baltica reconstruction halfway through, other half to be completed by 2025". The Baltic Times. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ a b c Lesiecki, Rafał (1 April 2022). "Przesmyk suwalski. Dlaczego jest tak ważny dla NATO" [Suwałki Gap. Why is it so important to NATO]. TVN24 (in Polish). Archived from the original on 16 April 2022. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ^ Madrjas, Jakub (19 February 2024). "Kolejne opóźnienie polskiej Rail Balitca. Najwcześniej 2028 rok". Rynek Kolejowy (in Polish). Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ "Gas from Lithuania flowing into Poland from May 2, climate minister says". The First News. 2 May 2022. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ Strzelecki, Marek; Starn, Jesper; Seputyte, Milda (9 December 2015). "Russia's Power Grip Over Baltics Ending With Billion-Euro Cables". Bloomberg. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ Sawicki, Bartłomiej (13 November 2023). "Polska i Litwa mogą wrócić do budowy drugiego lądowego mostu energetycznego". Rzeczpospolita (in Polish). Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Wang, Xiaoyong; Zhang, Jun; Wandelt, Sebastian (June 2023). "On the ramifications of airspace bans in aero-political conflicts: Towards a country importance ranking". Transport Policy. 137: 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2023.04.003. PMC 10106281. PMID 37091497.

- ^ "EU imposes sanctions, cuts air links with Belarus over plane 'hijacking'". France 24. 24 May 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ Nations, Madeleine (14 October 2020). "Kaliningrad: Russia's Best-Kept Strategic Secret". Glimpse from the Globe. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ a b Frühling, Stephan; Lasconjarias, Guillaume (3 March 2016). "NATO, A2/AD and the Kaliningrad Challenge". Survival. 58 (2): 95–116. doi:10.1080/00396338.2016.1161906. ISSN 0039-6338. S2CID 155598277. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ a b "The Russia - NATO A2AD Environment". Missile Threat - Center for Strategic and International Studies. 3 January 2017. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Piątek, Marcin (17 May 2022). "Przesmyk suwalski: rejon wrażliwy" [Suwałki Gap: a sensitive area]. Polityka (in Polish). Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ a b Howard, Glen (2017). "Baltic security in the age of Trump". Security in the Baltic Sea region: realities and prospects : the Rīga Conference papers 2017. Andris Sprūds, Māris Andžāns. Riga: Latvian Institute of International Affairs. p. 111. ISBN 978-9934-567-10-0. OCLC 1005143446. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ McLeary, Paul (1 October 2015). "Is NATO's New Fulda Gap in Poland?". Atlantic Council. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ "If Russia ever acts against NATO, US soldiers at Suwalki Gap may be first to fight back". Stars and Stripes. 18 May 2021. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ McLeary, Paul. "Meet the New Fulda Gap". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ a b Kowalczewski, Jan (2018). "Znaczenie polityczno-militarne przesmyku suwalskiego" [Political and military significance of the Suwałki Gap]. Przegląd Geopolityczny (in Polish) (25): 104–115. ISSN 2080-8836. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Doran, Peter B.; Wojcik, Ray (2018). Unfinished Business: Why and How the U.S. Should Establish a Permanent Military Presence on NATO's Eastern Flank (PDF). Washington, DC: Center for European Policy Analysis. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Deni, John R. (29 June 2017). "The NATO-Russia Founding Act: A Dead Letter". Carnegie Moscow Center. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Russia deploys Iskander nuclear-capable missiles to Kaliningrad: RIA". Reuters. 5 February 2018. Archived from the original on 13 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Kalus, Dominik (28 February 2022). "Atomwaffen: Nukleare Naivität - Plötzlich im Schatten der Atomraketen" [Nuclear Weapons: Nuclear Naivety - Suddenly in the shadow of nuclear missiles]. Die Welt (in German). Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Klein, Robert M.; Lundqvist, Stephan; Sumangil, Ed; Pettersson, Ulrica (November 2019). "Baltics Left of Bang: The Role of NATO with Partners in Denial-Based Deterrence". Strategic Forum. National Defense University. ProQuest 2321876856. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022 – via Proquest.

- ^ "Strengthening the Defense of NATO's Eastern Frontier". Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. Archived from the original on 10 February 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ Clark, Wesley; Luik, Jüri; Ramms, Egon; Shirreff, Richard (2016). Closing NATO's Baltic gap (PDF). International Centre for Defence and Security. Tallinn, Estonia. ISBN 978-9949-9448-7-3. OCLC 952565467. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Scholtz, Leopold (October 2020). "The Suwalki GAP dilemma: A strategic and operational analysis". Scientia Militaria. 48 (1): 23–40. doi:10.5787/48-1-1293. S2CID 225140998. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Kulesa, Łukasz (2019). "Wzmocnienie obecności wojskowej USA w Polsce: perspektywa amerykańskich think tanków" [Strengthening the US military presence in Poland: the perspective of American think tanks]. Polski Przegląd Dyplomatyczny (in Polish). 77 (2): 104–119. ISSN 1642-4069. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "NATO's military presence in the east of the Alliance". NATO. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Antczak, Anna; Śliwa, Zdzisław (12 December 2018). "Security dilemmas of the Baltic region". Środkowoeuropejskie Studia Polityczne (3): 119–134. doi:10.14746/ssp.2018.3.8. ISSN 1731-7517. S2CID 189010470. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Kulha, Shari (22 March 2022). "How the little-known Suwalki Corridor could largely block NATO assistance to Baltic states". National Post. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Military Presence in Poland". Congressional Research Service. 4 August 2020. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ Iriarte, Daniel (21 August 2017). "El 'corredor de Suwalki', la franja de la que depende la seguridad de Europa" [The 'Suwalki corridor', the strip on which Europe's security depends]. El Confidencial (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Miłosz, Maciej (12 March 2024). "Za dwa dni kończą się ćwiczenia Dragon-24. Wniosek? Potrzeba takich więcej". Forsal (in Polish). Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Brzozowski, Alexandra (24 February 2022). "NATO to beef up Eastern flank defence, hold summit after Russian attack on Ukraine". Euractiv. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ "Nato head assures Poland, Lithuania of alliance's protection". The First News. 31 March 2022. Archived from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ "NATO plans full-scale military presence at border, says Stoltenberg". Reuters. 11 April 2022. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Brzozowski, Alexandra (20 June 2022). "EU says Lithuania acted 'by the book' in Kaliningrad standoff with Russia". Euractiv. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ "Landsbergis: NATO no longer bound by promise to Russia not to boost forces in East". DELFI. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ^ "Mircea Geoană, secretarul general adjunct al NATO: "România este o ancoră strategică pentru NATO"" [Mircea Geoană, Deputy Secretary General of NATO: "Romania is a strategic anchor for NATO"]. www.antena3.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ "NATO feared Russia's Suwałki Gap threat. It's now much smaller". Euronews. 28 September 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ "Germany ready to "essentially contribute" to formation of NATO brigade in Lithuania". DELFI. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ Bennhold, Katrin (23 March 2022). "Germany Is Ready to Lead Militarily. Its Military Is Not". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 28 April 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ a b Roblin, Sebastien (26 June 2021). "In a Russia-NATO War, the Suwalki Gap Could Decide World War III". The National Interest. Archived from the original on 26 June 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Gady, Franz-Stefan (22 April 2024). "NATO's Confusion Over the Russia Threat". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ "New infrastructure for Lithuanian, allied troops to be built in Rukla – ministry". lrt.lt. 8 November 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Peseckyte, Giedre (15 April 2022). "Lithuania to set up new military training ground". www.euractiv.com. Archived from the original on 16 April 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Lithuania opens Rūdninkai military training area". lrt.lt. 2 June 2022. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ "Battle Group Poland's Storm Battery fires for effect". NATO Multinational Corps Northeast. 2 November 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "'The Russians could come any time': fear at Suwałki Gap on EU border". The Guardian. 25 June 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ Frisell, Eva Hagström; Pallin, Krister, eds. (2021). Western Military Capability in Northern Europe 2020. Part II: National Capabilities. Stockholm: Swedish Defence Research Agency. p. 86. Archived from the original on 16 April 2022. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ^ Thomas, Matthew (27 February 2020). "Defending the Suwałki Gap". Baltic Security Foundation. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "What is NATO's Response Force, and why is it being activated?". News @ Northeastern. 25 February 2022. Archived from the original on 27 February 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Nato to put 300,000 troops on high alert in response to Russia threat". The Guardian. 27 June 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ "Russia adds firepower to Kaliningrad exclave citing NATO threat". Reuters. 7 December 2020. Archived from the original on 28 April 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d Muzyka, Konrad (2021). Russian Forces in the Western Military District (PDF). Arlington, Va.: Center for Naval Analyses. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ a b Westerlund, Fredrik (May 2017). "FOI Memo 6060: Russia's Military Strategy and Force Structure in Kaliningrad" (PDF). Swedish Defence Research Agency.

- ^ "Военную группировку в Калининградской области усилили танками Т-72Б3М". Российская газета. 7 October 2021. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Балтфлот пополнился новыми усовершенствованными танками". РБК (in Russian). 7 November 2021. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ Kallberg, Jan; Hamilton, Stephen; Sherburne, Matthew (28 May 2020). "Electronic Warfare in the Suwalki Gap: Facing the Russian "Accompli Attack"". National Defense University Press. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "Russia defends right to deploy missiles after Kaliningrad rebuke". Reuters. 6 February 2018. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Kaliningrad photos appear to show Russia upgrading nuclear weapons bunker". The Guardian. 18 June 2018. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Russia warns of nuclear weapons in Baltic if Sweden and Finland join Nato". The Guardian. 14 April 2022. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Lithuanian officials puzzled by Russia's threat to deploy nuclear weapons in Kaliningrad". LRT. 14 April 2022. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Wilk, Andrzej (2021). Rosyjska armia białoruska: praktyczne aspekty integracji wojskowej Białorusi i Rosji (PDF) (in Polish). Warsaw: Centre for Eastern Studies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ a b Piss, Piotr (1 June 2018). "'Belarus – a significant chess piece on the chessboard of regional security". Journal on Baltic Security. 4 (1): 39–54. doi:10.2478/jobs-2018-0004. ISSN 2382-9230. S2CID 55095725.

- ^ Dyner, Anna Maria (2017). "The Armed Forces of Belarus". The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs. 26 (1): 38–58. ISSN 1230-4999.

- ^ Orzech, Krzysztof (2021). "The threats to Poland posed by the Republic of Belarus in the context of the crisis situation on the Polish-Belarusian border" (PDF). National Security Studies (Poland) (in Polish). 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Kofman, Michael (8 September 2021). "Zapad-2021: What to Expect From Russia's Strategic Military Exercise". War on the Rocks. Archived from the original on 30 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Лукашенко сообщил о закупке у России ракет "Искандер" и С-400". РБК (in Russian). 19 May 2022. Archived from the original on 14 June 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ Matthews, Owen (21 March 2022). "The Putin show: what Russians really watch on TV". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ Aristov, V.V.; Kovalev, V.I.; Belonozhkin, V.V.; Mitrofanova, S.V. (December 2019). "Методика оценки эффективности выполнения огневых задач подразделениями армейской авиации в тёмное время суток с учётом метеорологических условий" (PDF). Оперативное исскуство и тактика. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Schmies, Oxana (30 April 2021). NATO's Enlargement and Russia. Columbia University Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-3-8382-1478-8.

- ^ Milne, Richard (20 February 2022). "Baltic states fear encirclement as Russia security threat rises". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ a b Frisell, Eva Hagström; Pallin, Krister, eds. (2021). Western Military Capability in Northern Europe 2020. Part I: Collective Defence. Stockholm: Swedish Defence Research Agency. pp. 54, 104–108. Archived from the original on 16 April 2022. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ^ Klocek, Faustyna (2018). "Mocarstwowa polityka Federacji Rosyjskiej współczesnym zagrożeniem dla bezpieczeństwa Polski i regionu Morza Bałtyckiego". De Securitate et Defensione. O Bezpieczeństwie i Obronności (in Polish). 4 (2): 145–157. ISSN 2450-5005. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022 – via CEEOL.

- ^ Kofman, Michael (12 October 2018). "Permanently Stationing U.S. Forces in Poland is a Bad Idea, But One Worth Debating". War on the Rocks. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ^ a b Lanoszka, Alexander (14 July 2022). "Myths and misconceptions around Russian military intent: Myth 2: 'The Suwałki Gap matters'". Chatham House. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ "Putin 'is ready to invade Ukraine in the new year'". The Times. 6 December 2021. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Ciobanu, Claudia (15 November 2022). "Fog of War Thickens on Poland-Russia Border at Kaliningrad". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ a b Axe, David (26 October 2019). "The Suwalki Gap Is NATO's Achilles' Heel and the Place Where Russia Could Start War". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Shlapak, David A.; Johnson, Michael (29 January 2016). "Reinforcing Deterrence on NATO's Eastern Flank: Wargaming the Defense of the Baltics". RAND Corporation. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "MP: Finland NATO accession would radically change Estonian security". ERR News. 8 April 2022. Archived from the original on 28 April 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Estonian ambassador: Finland likely to join NATO by end of year". ERR. 18 April 2022. Archived from the original on 26 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Drozdziak, Natalia (14 May 2022). "NATO Expansion Could Finally Shore Up Alliance's Weakest Flank". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ "Sondaż: Zdecydowana większość Rosjan popiera inwazję Rosji. Kolejny cel: Polska". Rzeczpospolita (in Polish). Archived from the original on 16 April 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ "86,6% росіян підтримує збройне вторгнення РФ". Active Group (in Ukrainian). 16 March 2022. Archived from the original on 20 April 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ Schut, Marnix (2019). "Resilience in the Baltics". Atlantisch Perspectief. 43 (1): 31–34. ISSN 0167-1847. JSTOR 48581474. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ a b Deni, John R. "NATO Must Prepare to Defend Its Weakest Point—the Suwalki Corridor". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Bałuka, Mateusz (5 February 2021). "Ćwiczenia Zima-20: Przegrana polskiej armii w pięć dni. "Wnioski można wyciągać, jak rozegra się ich kilkaset"". Onet Wiadomości (in Polish). Archived from the original on 30 December 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ a b "How Does the Next Great Power Conflict Play Out? Lessons from a Wargame". War on the Rocks. 22 April 2019. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ a b Zagórski, Sławek (29 January 2021). "Zima 20. Czy manewry obnażyły słabość Polski?". geekweek.interia.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Wargame Study Shows Polish Armed Forces Obliterated in 5 Days - Overt Defense". Overt Defense. 31 March 2021. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Ćwiczenia Zima-20: Przegrana polskiej armii w pięć dni. "Wnioski można wyciągać, jak rozegra się ich kilkaset"". Onet Wiadomości (in Polish). 5 February 2021. Archived from the original on 30 December 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Zagórski, Sławek (8 February 2021). "Polska przegrała w pięć dni? Minister: Oceniam ćwiczenia na szóstkę!". geekweek.interia.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Michalski, Daniel (2017). "Powszechna samoobrona w rejonie przesmyku suwalskiego jako warunek konieczny zapewnienia bezpieczeństwa ludności cywilnej" (PDF). State Vocational College in Suwałki (in Polish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Journal, Daniel Michaels / Photographs by Anna Liminowicz (7 August 2022). "Russian Aggression Brings High Anxiety to Polish Border Towns". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Blocking the Bear: NATO Forward Defense of the Baltics". Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA). 7 November 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Permanent Military Base in Poland: Favorable Solution For the NATO Alliance". Warsaw Institute. 11 February 2019. Archived from the original on 2 February 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Lanoszka, Alexander; Hunzeker, Michael A. (2019). Conventional deterrence and landpower in Northeastern Europe (PDF). Carlisle, Pa.: Strategic Studies Institute/U.S. Army War College Press. ISBN 978-1584878049. OCLC 1101187145. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Hunzeker, Michael A.; Lanoszka, Aleksander (26 March 2019). "Threading the Needle Through the Suwałki Gap". EastWest Institute. Archived from the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Mastriano, Douglas, ed. (2017). Project 1721 : a U.S. Army War College assessment on Russian strategy in Eastern Europe and recommendations on how to leverage landpower to maintain the peace (PDF). Carlisle, Pa.: Strategic Studies Institute/Army War College Press. ISBN 978-1584877455. OCLC 978349452. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Sokov, Nikolai (1 May 2019). "How NATO Could Solve the Suwalki Gap Challenge". The National Interest. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Russia, NATO Lock Eyes as Rivals Flex Military Muscle". NBC News. 7 December 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Coyle, James J. (15 April 2018). "Defending the Baltics is a conundrum". The Hill. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

Further reading

edit- Bębenek, Bogusław; Maj, Julian; Maksimczuk, Aleksander; Sęk, Andrzej; Soroka, Paweł; Wiszniewska, Marta (2020). Przesmyk suwalski w warunkach kryzysu i wojny : aspekty obronne i administracyjne : konferencja naukowa, Suwałki, 9-10 maja 2019 roku [Suwałki Gap in the conditions of crisis and war: defense and administrative aspects: scientific conference, Suwałki, May 9–10, 2019] (in Polish). Suwałki: Wydawnictwo Uczelniane Państwowej Wyższej Szkoły Zawodowej w Suwałkach. ISBN 978-83-951182-3-4. OCLC 1241633779.

- Bełdyga, Natalia (2023). "Analiza dyskursu medialnego o ryzyku i niepewności przesmyka suwalskiego w ogólnopolskich i zagranicznych mediach". In Całek, Grzegorz (ed.). Młoda socjologia o społeczeństwie (in Polish). Kraków: Oficyna Wydawnicza Impuls. pp. 90–107. ISBN 978-83-8294-285-9.

- Birnbaum, Michael (24 June 2018). "If they needed to fend off war with Russia, U.S. military leaders worry they might not get there in time". The Washington Post.

- Rynning, Sten; Schmitt, Olivier; Theussen, Amelie (2 March 2021). War Time: Temporality and the Decline of Western Military Power. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 978-0-8157-3895-4.

- Sirutavičius, Vladas; Stanytė - Toločkienė, Inga (18 July 2003). "Strategic Importance of Kaliningrad Oblast of the Russian Federation". Lithuanian Annual Strategic Review. 1 (1): 181–214. doi:10.47459/lasr.2003.1.9. ISSN 1648-8024.

- Szymanowski, Karol (2017). "Air Defense in a Specific Environment of the Suwalki Isthmus". Safety & Defense. 3: 25–30. doi:10.37105/sd.19. ISSN 2450-551X. S2CID 210787561.

- van Dijk, Fieke Margaretha (2024). A risk of conflict – Perception or Reality? : A media study of securitization and strategic narratives in the Suwałki Gap. Institute for Russian and Eurasian Studies - Uppsala University.

- Veebel, Viljar (4 May 2019). "Why it would be strategically rational for Russia to escalate in Kaliningrad and the Suwalki corridor". Comparative Strategy. 38 (3): 182–197. doi:10.1080/01495933.2019.1606659. ISSN 0149-5933. S2CID 197814562.; publicly accessible version: online

- Zverev, Yury (2021). "Possible Directions of NATO Military Operations Against the Kaliningrad Region of the Russian Federation (Based on Materials from Open Publications)". Eurasia. Expert (in Russian) (2): 44–53. doi:10.18254/S271332140015330-0. ISSN 2713-3214. S2CID 244319068.