The 1971 San Fernando earthquake (also known as the 1971 Sylmar earthquake) occurred in the early morning of February 9 in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains in southern California. The unanticipated thrust earthquake had a magnitude of 6.5 on the Ms scale and 6.6 on the Mw scale, and a maximum Mercalli intensity of XI (Extreme). The event was one in a series that affected Los Angeles County during the late 20th century. Damage was locally severe in the northern San Fernando Valley and surface faulting was extensive to the south of the epicenter in the mountains, as well as urban settings along city streets and neighborhoods. Uplift and other effects affected private homes and businesses.

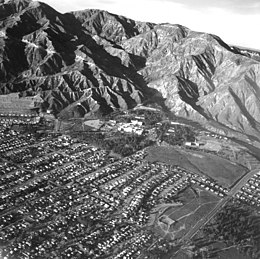

The San Gabriel Mountains with the Veterans Hospital in center (above) and selected cities with reported felt intensity in the US (see intensity table) | |

| UTC time | 1971-02-09 14:00:41 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 787038 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | February 9, 1971 |

| Local time | 06:00:41 PST |

| Duration | 12 seconds[1] |

| Magnitude | 6.5 Ms;[2] 6.6 Mw[3] |

| Depth | 8.4 km (5.2 mi)[2] |

| Epicenter | 34°16′N 118°25′W / 34.27°N 118.41°W[2] |

| Fault | Sierra Madre Fault Zone |

| Type | Oblique-thrust |

| Areas affected | Greater Los Angeles Area Southern California United States |

| Total damage | $505–553 million[4][5] |

| Max. intensity | MMI XI (Extreme)[6] |

| Peak acceleration | 1.25 g at Pacoima Dam[7] |

| Landslides | 1,000+ |

| Casualties | 58–65 dead[4] 200–2,000 injured[4] |

The event affected a number of health-care facilities in Sylmar, San Fernando, and other densely populated areas north of central Los Angeles. The Olive View Medical Center and Veterans Hospital both experienced very heavy damage, and buildings collapsed at both sites, causing the majority of deaths that occurred. The buildings at both facilities were constructed with mixed styles, but engineers were unable to thoroughly study the buildings' responses because they were not outfitted with instruments for recording strong ground motion; this prompted the Veterans Administration to later install seismometers at its high-risk sites. Other sites throughout the Los Angeles area had been instrumented as a result of local ordinances, and an unprecedented amount of strong motion data was recorded, more so than any other event up until that time. The success in this area spurred the initiation of California's Strong Motion Instrumentation Program.

Transportation around the Los Angeles area was severely afflicted with roadway failures and the partial collapse of several major freeway interchanges. All 4,084 square miles of Los Angeles County were declared a disaster area by California Governor Ronald Reagan.[8] The near total failure of the Lower Van Norman Dam resulted in the evacuation of tens of thousands of downstream residents, though an earlier decision to maintain the water at a lower level may have contributed to saving the dam from being overtopped. Schools were affected, as they had been during the 1933 Long Beach earthquake, but this time amended construction styles improved the outcome for the thousands of school buildings in the Los Angeles area. Another result of the event involved the hundreds of various types of landslides that were documented in the San Gabriel Mountains. As had happened following other earthquakes in California, legislation related to building codes was once again revised, with laws that specifically addressed the construction of homes or businesses near known active fault zones.

Tectonic setting

editThe San Gabriel Mountains are a 37.3 mi (60.0 km) long portion of the Transverse Ranges and are bordered on the north by the San Andreas Fault, on the south by the Cucamonga Fault, and on the southwest side by the Sierra Madre Fault. The San Bernardino, Santa Ynez, and Santa Monica Mountains are also part of the anomalous east–west trending Transverse Ranges. The domain of the ranges stretches from the Channel Islands offshore to the Little San Bernardino Mountains, 300 miles (480 km) to the east. The frontal fault system at the base of the San Gabriel Mountains extends from the San Jacinto Fault Zone in the east to offshore Malibu in the west, and is defined primarily by moderate to shallow north-dipping faults, with a conservative vertical displacement estimated at 4,000–5,000 feet (1,200–1,500 m).[9]

Paleomagnetic evidence has shown that the western Transverse Ranges were formed as the Pacific plate moved northward relative to the North American plate. As the plate shifted to the north, a portion of the terrane that was once parallel with the coast was rotated in a clockwise manner, which left it positioned in its east–west orientation. The Transverse Ranges form the perimeter of a series of basins that begins with the Santa Barbara Channel on the west end. Moving eastward, there is the Ventura Basin, the San Fernando Valley, and the San Gabriel Basin, with active reverse faults (San Cayetano, Red Mountain, Santa Susana, and Sierra Madre) all lining the north boundary. A small number of damaging events have occurred, with three in Santa Barbara (1812, 1925, and 1978) and two in the San Fernando Valley (1971 and 1994), though other faults in the basin that have high Quaternary slip rates have not produced any large earthquakes.[10]

Earthquake

editThe San Fernando earthquake occurred on February 9, 1971, at 6:00:41 am Pacific Standard Time (14:00:41 UTC) with a strong ground motion duration of about 12 seconds as recorded by seismometers,[11] although the whole event was reported to have lasted about 60 seconds.[6] The origin of faulting was located five miles north of the San Fernando Valley. Considerable damage was seen in localized portions of the valley and also in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains above the fault block. The fault that was responsible for the movement was not one that had been considered a threat, and this highlighted the urgency to identify other similar faults in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. The shaking surpassed building code requirements and exceeded what engineers had prepared for, and although most dwellings in the valley had been built in the prior two decades, even modern earthquake-resistant structures sustained serious damage.[12]

Several key attributes of the event were shared with the 1994 Northridge earthquake, considering both were brought about by thrust faults in the mountains north of Los Angeles, and each resulting earthquake being similar in magnitude, though no surface rupture occurred in 1994. Since both occurred in urban and industrial areas and resulted in significant economic impairment, each event drew critical observation from planning authorities, and has been thoroughly studied in the scientific communities.[13]

Surface faulting

editProminent surface faulting trending N72°W was observed along the San Fernando Fault Zone from a point south of Sylmar, stretching nearly continuously for 6 miles (9.7 km) east to the Little Tujunga Canyon. Additional breaks occurred farther to the east that were in a more scattered fashion, while the western portion of the most affected area had less pronounced scarps, especially the detached Mission Wells segment. Although the complete Sierra Madre Fault Zone had previously been mapped and classified by name into its constituent faults, the clusters of fault breaks provided a natural way to identify and refer to each section. As categorized during the intensive studies immediately following the earthquake, they were labeled the Mission Wells segment, Sylmar segment, Tujunga segment, Foothills area, and the Veterans fault.[14][15]

All segments shared the common elements of thrust faulting with a component of left-lateral slip, a general east–west strike, and a northward dip, but they were not unified with regard to their connection to the associated underlying bedrock. The initial surveyors of the extensive faulting in the valley, foothills, and mountains reported only tectonic faulting, while excluding fissures and other features that arose from the effects of compaction and landslides. In the vicinity of the Sylmar Fault segment, there was a low possibility of landslides due to a lack of elevation change, but in the foothills and mountainous area a large amount of landslides occurred and more work was necessary to eliminate the possibility of misidentifying a feature. Along the hill fronts of the Tujunga segment, some ambiguous formations were present because some scarps may have had influence from downhill motion, but for the most part they were tectonic in nature.[14]

In repeated measurements of the different fault breaks, the results remained consistent, leading to the belief that most of the slip had occurred during the mainshock. While lateral, transverse, and vertical motions were all observed, the largest individual component of movement was 5 ft 3 in (1.60 m) of left lateral slip near the middle of the Sylmar segment. The largest cumulative amount of slip of 6 feet 7 inches (2.01 m) occurred along the Sylmar and Tujunga segments. The overall fault displacement was summarized by geologist Barclay Kamb and others as "nearly equal amounts of north–south compression, vertical uplift (north side up), and left lateral slip and hence may be described as a thrusting of a northern block to the southwest over a southern block, along a fault surface dipping about 45° north."[16]

Landslides

editThe USGS commissioned a private company and the United States Air Force to take aerial photographs over 97 sq mi (250 km2) of the mountainous areas north of the San Fernando Valley. Analysis revealed that the earthquake triggered over 1,000 landslides. Highly shattered rock was also documented along the ridge tops, and rockfalls (which continued for several days) were the result of both the initial shock and the aftershocks. Few of the slides that were logged from the air were also observed from the ground. The greatest number of slides were centered to the southwest of the mainshock epicenter and close to the areas where surface faulting took place. The slides ranged from 49–984 feet (15–300 m) in length, and could be further categorized as rock falls, soil falls, debris slides, avalanches, and slumps. The most frequently encountered type of slide was the surficial (less than 3 feet (0.91 m) thick) debris slides and were most often encountered on terrain consisting of sedimentary rock.[17]

Strong motion

editIn early 1971, the San Fernando Valley was the scene of a dense network of strong-motion seismometers, which provided a total of 241 seismograms. This made the earthquake the most documented event, at the time, in terms of strong-motion seismology; by comparison, the 1964 Alaska earthquake did not provide any strong motion records. Part of the reason there were so many stations to capture the event was a 1965 ordinance that required newly constructed buildings in Beverly Hills and Los Angeles over six stories in height to be outfitted with three of the instruments. This stipulation ultimately found its way into the Uniform Building Code as an appendix several years later. One hundred seventy-five of the recordings came from these buildings, another 30 were on hydraulic structures, and the remainder were from ground-based installations near faults, including an array of the units across the San Andreas Fault.[18]

The instrument that was installed at the Pacoima Dam recorded a peak horizontal acceleration of 1.25 g, a value that was twice as large as anything ever seen from an earthquake. The extraordinarily high acceleration was just one part of the picture, considering that duration and frequency of shaking also play a role in how much damage can occur. The accelerometer was mounted on a concrete platform on a granite ridge just above one of the arch dam's abutments. Cracks formed in the rocks and a rock slide came within 15 feet (4.6 m) of the apparatus, and the foundation remained undamaged, but a small (half-degree) tilt of the unit was discovered that was apparently responsible for closing the horizontal pendulum contacts. As a result of what was considered a fortunate accident, the machine kept recording for six minutes (until it ran out of paper) and provided scientists with additional data on 30 of the initial aftershocks.[18]

Damage

editThe areas that were affected by the strongest shaking were the outlying communities north of Los Angeles that are bounded by the northern edge of the San Fernando Valley at the base of the San Gabriel Mountains. The unincorporated districts of Newhall, Saugus, and Solemint Junction had moderate damage, even to newer buildings. The area where the heaviest effects were present was limited by geographical features on the three remaining margins, with the Santa Susana Mountains on the west, the Santa Monica Mountains and the Los Angeles River to the south, and along the Verdugo Mountains to the east. Loss of life that was directly attributable to the earthquake amounted to 58 (a number of heart attacks and other health-related deaths were not included in this figure). Most deaths occurred at the Veterans and Olive View hospital complexes, and the rest were located at private residences, the highway overpass collapses, and a ceiling collapse at the Midnight Mission in downtown Los Angeles.[19]

The damage was greatest near and well north of the surface faulting, and at the foot of the mountains. The hospital buildings, the freeway overpasses, and the Sylmar Juvenile Hall were on coarse alluvium that overlay thousands of feet of loosely consolidated sedimentary material. In the city of San Fernando, underground water, sewer, and gas systems suffered breaks too numerous to count, and some sections were so badly damaged that they were abandoned. Ground displacement damaged sidewalks and roads, with cracks in the more rigid asphalt and concrete often exceeding the width of the shift in the underlying soil. Accentuated damage near alluvium had been documented during the investigation of the effects of the 1969 Santa Rosa earthquakes. A band of similarly intense damage further away near Ventura Boulevard at the southern end of the valley was also identified as having been related to soil type.[20]

Federal, county, and private hospitals suffered varying degrees of damage, with four major facilities in the San Fernando Valley suffering structural damage, and two of those collapsing. The Indian Hills Medical Center, the Foothill Medical Building, and the Pacoima Lutheran Professional building were heavily damaged. Nursing homes also were affected. The one-story Foothill Nursing Home sat very close to a section of the fault that broke the surface and was raised up three feet higher than the street. Scarps ran along the sidewalk and across the property. The building was not in use and remained standing. Though the reinforced concrete block structure was afflicted by the shock and uplift, the relatively good performance was in stark contrast to that of the Olive View and Veterans Hospital complexes.[21]

Olive View Hospital

editMost of the buildings at the Los Angeles County–owned, 880-bed hospital complex had been built before the adoption of new construction techniques that had been put in place after the 1933 Long Beach earthquake. The group of one-story structures 300 feet west of the new facility, and some other buildings, were not damaged. The damaged buildings variously were wood-frame and masonry structures. The five-story, reinforced-concrete Medical Treatment and Care Building was one of three new additions to the complex (all three of which sustained damage), was assembled with earthquake-resistant construction techniques, and was completed in December 1970. The hospital was staffed by 98 employees and had 606 patients at the time of the earthquake; all three deaths that occurred at the Olive View complex were in this building. Two deaths were due to power failure of life-support systems and one employee was struck by part of the collapsing building while trying to exit the building.[21]

The Medical Treatment and Care Building included a basement that was exposed (above grade) on the east and south sides, mixed (above and below grade) on the west side, and below grade on the north side of the building, the variation being due to the shallow slope at the site. The complete structure, including the four external staircases, could be considered five separate buildings, because the stair towers were detached from the main building by about four inches. Earthquake bracing used in the building's second through fifth floors consisted of shear walls, but a rarely used slip joint technique used with the concrete walls at the first floor kept them from being part of that system. Damage to the building, including ceiling tiles, telephone equipment, and elevator doors, was excessive at the basement and the first floor, with little damage further up. The difference in rigidity at the second floor was proposed as a cause of the considerable damage to the lower levels. Because the first floor almost collapsed, the building was leaning to the north by almost two feet, and three of the four concrete stair towers fell away from the main building.[21]

On the grounds, there were cracks in the pavement and soil, but no surface faulting. In addition to the collapse of the stairways, the elevators were out of commission. Electrical power and communications failed at the hospital at the time of the earthquake, but very few people occupied the lower floors and the stairways at the early hour. Casualties in these highly affected areas might have increased had the shock occurred later in the day. The duration of strong ground motion at that location was probably similar to the 12 seconds observed at the Pacoima Dam, and it is thought that another few seconds' shaking might have been enough to bring the building to collapse.[21]

Veterans Administration Hospital

editThe Veterans Administration Hospital entered into service as a tuberculosis hospital in 1926 and became a general hospital in the 1960s. By 1971, the facility comprised 45 individual buildings, all lying within 5 km (3.1 mi) of the fault rupture in Sylmar, but the structural damage was found to have occurred as a result of the shaking and not from ground displacement or faulting. Twenty-six buildings that were built prior to 1933 had been constructed following the local building codes and did not require seismic-resistant designs. These buildings suffered the most damage, with four buildings totally collapsing, which resulted in a large loss of life at the facility. Most of the masonry and reinforced concrete buildings constructed after 1933 withstood the shaking and most did not collapse, but in 1972 a resolution came forth to abandon the site and the remaining structures were later demolished, the site becoming a city park.[22]

Few strong motion seismometer installations were present outside of the western United States prior to the San Fernando earthquake but, upon a recommendation by the Earthquake and Wind Forces Committee, the Veterans Administration entered into an agreement with the Seismological Field Service (then associated with NOAA) to install the instruments at all VA sites in Uniform Building Code zones two and three. It had been established that these zones had a higher likelihood of experiencing strong ground acceleration, and the plan was made to furnish the selected VA hospitals with two instruments. One unit would be installed within the structure and the second would be set up as a free-field unit located a short distance away from the facility. As of 1973, a few of the highest risk (26 were completed in zone 3 alone) sites that had been completed were in Seattle, Memphis, Charleston, and Boston.[22]

Van Norman Dam

editBoth the Upper and Lower Van Norman Dams were severely damaged as a result of the earthquake. The lower dam was very close to breaching, and approximately 80,000 people were evacuated for four days while the water level in the reservoir was lowered. This was done as a precaution to accommodate further collapse due to a strong aftershock. Some canals in the area of the dams were damaged and not usable, and dikes experienced slumping but these did not present a hazard. The damage at the lower dam consisted of a landslide that dislocated a section of the embankment. The earthen lip of the dam fell into the reservoir and brought with it the concrete lining, while what remained of the dam was just 5 feet (1.5 m) above the water level. The upper lake subsided 3 feet (0.91 m) and was displaced about 5 feet (1.5 m) as a result of the ground movement, and the dam's concrete lining cracked and slumped.[23]

The upper dam was constructed in 1921 with the hydraulic fill process, three years after the larger lower dam, which was fabricated using the same style. An inspection of the lower dam in 1964 paved the way towards an arrangement between the State of California and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power that would maintain the reservoir's water level that was reduced 10 feet lower than was typical. Since the collapse of the dam lowered its overall height, the decision to reduce its capacity proved to be a valuable bit of insurance.[23]

Differential ground motion and strong shaking (MMI VIII (Severe)) were responsible for serious damage to the Sylmar Juvenile Hall facility and the Sylmar Converter Station (both located close to the Upper Van Norman lake). The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, as well as the County of Los Angeles, investigated and verified that local soil conditions contributed to the ground displacement and resulting destruction. The area of surface breaks on the ground at the site was 900 ft (270 m) (at its widest) and stretched 4,000 ft (1,200 m) down a 1% grade slope towards the southwest. As much as 5 ft (1.5 m) of lateral motion was observed on either end of the slide, and trenches that were excavated during the examination at the site revealed that some of the cracks were up to 15 ft (4.6 m) deep. The two facilities, located near Grapevine and Weldon canyons that channel water and debris off the Sierra Madre Mountains, are lined by steep ridges and have formed alluvial fans at their mouths. The narrow band of ground disturbances were found to have been the result of settling of the soft soil in a downhill motion. Soil liquefaction played a role within confined areas of the slide, but it was not responsible for all the motion at the site, and tectonic slip of faults in the area was also excluded as a cause.[24]

Transportation

editSubstantial disruption to about 10 miles of freeways in the northern San Fernando Valley took place, with most of the damage occurring at the Foothill Freeway / Golden State Freeway interchange, and along a five-mile stretch of Interstate 210. On Interstate 5, the most significant damage was between the Newhall Pass interchange on the north end and the I-5 / I-405 interchange in the south, where subsidence at the bridge approaches and cracking and buckling of the roadway made it unusable. Several landslides occurred between Balboa Boulevard and California State Route 14, but the most significant damage occurred at the two major interchanges. The Antelope Valley Freeway had damage from Newhall Pass to the northeast, primarily from settling and alignment issues, as well as splintering and cracking at the Santa Clara River and Solemint bridges.[25]

- Golden State Freeway – Antelope Valley Freeway Interchange

While the Newhall Pass interchange was still under construction at the time of the earthquake, the requisite components of the overpass were complete. Vibration caused two of the bridge's 191-foot sections to fall from a maximum height of 140 ft (43 m), along with one of the supporting pillars. The spans slipped off of their supports at either end due to lack of proper ties and insufficient space (a 14 in (360 mm) seat was provided) on the support columns. Ground displacement at the site was ruled out as a major cause of the failure, and in addition to the fallen sections and a crane that was struck during the collapse, other portions of the overpass were also damaged. Shear cracking occurred at the column closest to the western abutment, and the ground at the same column's base exhibited evidence of rotation.[26]

- Golden State Freeway – Foothill Freeway Interchange

This interchange is a broad complex of overpasses and bridges that was nearly complete at the time of the earthquake and not all portions were open to traffic. Several instances of failure or collapse at the site took place and two men were killed while driving in a pickup truck as a result. The westbound I-210 to southbound I-5, which was complete except for paving at the ramp section, collapsed to the north, likely because of vibration that moved the overpass off its supports due to an inadequate seat. Unlike the situation at the Antelope Valley Interchange, permanent ground movement (defined as several inches of left-lateral displacement with possibly an element of thrusting) was observed in the area. The movement contributed to heavy damage at the Sylmar Juvenile Hall facility, Sylmar Converter Station, and the Metropolitan Water District Treatment Plant, but its effects on the interchange was not completely understood as of a 1971 report from the California Institute of Technology.[26]

Schools

editA large number of public school buildings in the Los Angeles area displayed mixed responses to the shaking, and those that were built after the enforcement of the Field Act clearly showed the results of the reformed construction styles. The Field Act was put into effect just one month following the destructive March 1933 Long Beach earthquake that damaged many public school buildings in Long Beach, Compton, and Whittier. The Los Angeles Unified School District had 660 schools consisting of 9,200 buildings at the time of the earthquake, with 110 masonry buildings that had not been reinforced to meet the new standards. More than 400 portable classrooms and 53 wood frame pre-Field Act buildings were also in use. All these buildings had been previously inspected with regard to the requirements of the Act, and many were reinforced or rebuilt at that time, but earthquake engineering experts recommended further immediate refurbishment or demolition after a separate evaluation was done after the February 1971 earthquake, and within a year and a half the district followed through with the direction with regard to about 100 structures.[27]

At Los Angeles High School (20 mi (32 km) from Pacoima Dam) where the exterior walls of the main pre-Field Act building (constructed 1917) were unreinforced brick masonry, long portions of the parapet and the associated brick veneer broke off and some fragments fell through the roof to a lower floor, while other material landed on an exit stairway and into a courtyard area. The main building was demolished at a cost of $127,000, and none of the various post-Field Act buildings were damaged at the site. Except for the concrete gymnasium, all of the buildings at Sylmar High School (3.75 mi (6.04 km) from Pacoima Dam) were post-Field Act, one-story, wood construction. Abundant cracks formed in the ground at the site, and some foundations and many sidewalks were also cracked. The estimate for repairs at the site was $485,000. At 2 mi (3.2 km), Hubbard Street Elementary School was the closest school to Pacoima dam and was also less than a mile from the Veterans Hospital complex. The wood-frame buildings (classrooms, a multipurpose building, and some bungalows) were built after the Field Act, and damage and cleanup costs there totaled $42,000. Gas lines were broken and separation of the buildings' porches was due to lateral displacement of up to six inches.[27]

Aftermath

editFollowing many of California's major earthquakes, lawmakers have acted quickly to develop legislation related to seismic safety. After the M6.4 1933 Long Beach earthquake, the Field Act was passed the following month, and after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, the Seismic Hazards Mapping Act and Senate Bill 1953 (hospital safety requirements) were established. Following the San Fernando event, earthquake engineers and seismologists from established scientific organizations, as well as the newly formed Los Angeles County Earthquake Commission, stated their recommendations that were based on the lessons learned. The list of items needing improvements included building codes, dams and bridges being made more earthquake resistant, hospitals that are designed to remain operational, and the restriction of development near known fault zones. New legislation included the Alquist-Priolo Special Studies Zone Act and the development of the Strong Motion Instrumentation Program.[28][29]

Alquist-Priolo Special Studies Zone Act

Introduced as Senate Bill 520 and signed into law in December 1972, this legislation was originally known as the Alquist-Priolo Geologic Hazard Zones Act, and had the goal of reducing damage and losses due to surface fault ruptures or fault creep. The act restricts construction of buildings designed for human occupancy across potentially active faults. Since it is presumed that surface rupture will likely take place where past surface displacement has occurred, the state geologist was given the responsibility for evaluating and mapping faults that had evidence of Holocene rupture, and creating regulatory zones around them called Earthquake Fault Zones. State and local agencies (as well as the property owner) were then responsible for enforcing or complying with the building restrictions.[29]

California Strong Motion Instrumentation Program

Prior to the San Fernando earthquake, some structural engineers had already believed that the existing groundwork for seismic design required enhancement. Although instruments had recorded a force of 0.33 g during the 1940 El Centro earthquake, building codes only required structures to withstand a lateral force of 0.1 g as late as the 1960s. Even at that time, engineers were against the idea of constructing buildings to resist the high forces that were seen in the El Centro shock, but after a 1966 earthquake peaked at 0.5 g, and a maximum of 1.25 g was observed at the Pacoima Dam during the San Fernando event, a debate began as to whether that low requirement was sufficient.[28]

Despite the compelling seismogram from the 1940 event in El Centro, strong-motion seismology was not explicitly sought until later events occurred—the San Fernando earthquake made evident the need for more data for earthquake engineering applications. The California Strong Motion Instrumentation Program was initiated in 1971 with the goal of maximizing the volume of data by furnishing and maintaining instruments at selected lifeline structures, buildings, and ground response stations. By the late 1980s, the program had instrumented more than 450 structures, bridges, dams, and power plants. The 1979 Imperial Valley and 1987 Whittier Narrows earthquakes were presented as gainful events that were recorded during that period, because both produced valuable data that increased knowledge of how moderate events affect buildings. The success of the Imperial Valley event was especially pronounced because of a recently constructed and fully instrumented government building that was shaken to the point of failure.[30][31]

See also

edit- 1994 Northridge earthquake, a magnitude 6.7 quake which affected many of the same areas

- California State Route 126

- Interstate 105 (California)

- List of earthquakes in 1971

- List of earthquakes in California

- Long Beach Search and Rescue

- San Gabriel Fault

- Wadsworth Chapel

References

edit- ^ Maley, R. P.; Cloud, W. K. (1971), "Preliminary strong motion results from the San Fernando earthquake of February 9, 1971", The San Fernando, California, earthquake of February 9, 1971; a preliminary report published jointly by the U.S. Geological Survey and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Geological Survey Professional Paper 733, United States Government Printing Office, p. 163, doi:10.3133/pp733, hdl:2027/uc1.31210020751366

- ^ a b c ISC-EHB Event 787038 [IRIS] (retrieved 2018-05-05).

- ^ ANSS: San Fernando 1971 (accessed 2018-05-05).

- ^ a b c PAGER-CAT Earthquake Catalog, Version 2008_06.1, United States Geological Survey, September 4, 2009

- ^ Reich, Kenneth (February 4, 1996). "'71 Valley Quake a Brush With Catastrophe". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012.

- ^ a b Stover, C. W.; Coffman, J. L. (1993), Seismicity of the United States, 1568–1989 (Revised) – U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1527, United States Government Printing Office, p. 92, archived from the original on April 13, 2019, retrieved April 3, 2016

- ^ Cloud & Hudson 1975, pp. 278, 287

- ^ Craven, Jasper (June 2024). "The Land War". Long Lead. Retrieved June 30, 2024.

- ^ Morton, D. M.; Baird, A. K. (1975), "Tectonic setting of the San Gabriel mountains", San Fernando, California, earthquake of 9 February 1971, Bulletin 196, California Division of Mines and Geology, pp. 3, 5

- ^ Yeats, R. (2012), Active Faults of the World, Cambridge University Press, pp. 111–114, ISBN 978-0-521-19085-5

- ^ Steinbrugge, Schader & Moran 1975, pp. 323

- ^ Steinbrugge, K. V.; Schader, E. E.; Bigglestone, H. C.; Weers, C. A. (1971). San Fernando Earthquake: February 9, 1971. Pacific Fire Rating Bureau. p. vii. Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

- ^ Bolt, B. (2005), Earthquakes: 2006 Centennial Update – The 1906 Big One (Fifth ed.), W. H. Freeman and Company, pp. 106–107, ISBN 978-0716775485

- ^ a b Kamb et al. 1971, pp. 41–43

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Staff (1971), "Surface Faulting", The San Fernando, California, earthquake of February 9, 1971; a preliminary report published jointly by the U.S. Geological Survey and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Geological Survey Professional Paper 733, United States Government Printing Office, p. 57, doi:10.3133/pp733, hdl:2027/uc1.31210020751366

- ^ Kamb et al. 1971, p. 44

- ^ Morton, D. M. (1971), "Seismically triggered landlslides in the area above the San Fernando Valley", The San Fernando, California, earthquake of February 9, 1971; a preliminary report published jointly by the U.S. Geological Survey and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Geological Survey Professional Paper 733, United States Government Printing Office, p. 99, doi:10.3133/pp733, hdl:2027/uc1.31210020751366

- ^ a b Cloud & Hudson 1975, pp. 273, 277, 287

- ^ Steinbrugge, Schader & Moran 1975, pp. 323–325

- ^ Steinbrugge, Schader & Moran 1975, pp. 350–353

- ^ a b c d Steinbrugge, Schader & Moran 1975, pp. 341–346

- ^ a b Bolt, B.; Johnston, R. G.; Lefter, J.; Sozen, M. A. (1975), "The study of earthquake questions related to Veterans Administration hospital facilities", Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 65 (4): 937, 938, 943–945, Bibcode:1975BuSSA..65..937B, doi:10.1785/BSSA0650040937, S2CID 132336432, archived from the original on September 23, 2015, retrieved May 20, 2013

- ^ a b Youd, T. L.; Olsen, H. W. (1971), "Damage to constructed works, associated with soil movements and foundation failures", The San Fernando, California, earthquake of February 9, 1971; a preliminary report published jointly by the U.S. Geological Survey and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Geological Survey Professional Paper 733, United States Government Printing Office, pp. 126–129, doi:10.3133/pp733, hdl:2027/uc1.31210020751366

- ^ Smith, J. L.; Fallgren, R. B. (1975), "Ground displacement at San Fernando Valley Juvenile Hall and the Sylmar Converter Station", San Fernando, California, earthquake of 9 February 1971, Bulletin 196, California Division of Mines and Geology, pp. 157–158, 163

- ^ California Division of Highways (1975), "Highway damage in the San Fernando earthquake", San Fernando, California, earthquake of 9 February 1971, Bulletin 196, California Division of Mines and Geology, p. 369

- ^ a b Jennings, P. C.; Wood, J. H. (1971), "Earthquake damage to freeway structures", Engineering features of the San Fernando earthquake of February 9, 1971, California Institute of Technology, pp. 366–385

- ^ a b Meehan, J. F. (1975), "Performance of public school buildings", San Fernando, California, earthquake of 9 February 1971, Bulletin 196, California Division of Mines and Geology, pp. 355, 356, 359–364

- ^ a b Geschwind, C. (2001). California Earthquakes: Science, Risk, and the Politics of Hazard Mitigation. Vol. 83. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 166, 170, 171. Bibcode:2002EOSTr..83...39S. doi:10.1029/2002EO000029. ISBN 978-0801865961.

- ^ a b Bryant, W. A. (2010). "History of the Alquist-Priolo Earthquake Fault Zoning Act, California, USA" (PDF). Environmental & Engineering Geoscience. XVI (1): 7–10. Bibcode:2010EEGeo..16....7B. doi:10.2113/gseegeosci.16.1.7. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 16, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- ^ Lee, W. H. K. (2002), "Challenges in observational seismology", International Handbook of Earthquake & Engineering Seismology, Part A, Volume 81A (First ed.), Academic Press, p. 273, ISBN 978-0124406520

- ^ Shakal, A. F.; Huang, M.; Ventura, C. E. (1988). The California Strong Motion Instrumentation Program: Objectives, Status, and Recent Data (PDF). from the 9th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Tokoyo, Japan, August 2–9, 1988. pp. 1–4.

Sources

- ANSS, "San Fernando 1971: M 6.6 – 10 km SSW of Agua Dulce, CA", Comprehensive Catalog, U.S. Geological Survey

- International Seismological Centre. ISC-EHB Bulletin. Thatcham, United Kingdom.

- Allen, C.; Hanks, T. C.; Whitcomb, J. H. (1975), "Seismological studies of the San Fernando earthquake and their tectonic implications", San Fernando, California, earthquake of 9 February 1971, Bulletin 196, California Division of Mines and Geology, pp. 257–262.

- Cloud, W. K.; Hudson, D. E. (1975), "Strong motion data from the San Fernando, California, earthquake of February 9, 1971", San Fernando, California, earthquake of 9 February 1971, Bulletin 196, California Division of Mines and Geology, pp. 273–303.

- Kamb, B.; Silver, L. T.; Abrams, M. J.; Carter, B. A.; Jordan, T. H.; Minister, J. B. (1971), "Pattern of faulting and nature of fault movement in the San Fernando earthquake", The San Fernando, California, earthquake of February 9, 1971; a preliminary report published jointly by the U.S. Geological Survey and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Geological Survey Professional Paper 733, United States Government Printing Office, pp. 41–54, doi:10.3133/pp733, hdl:2027/uc1.31210020751366.

- Steinbrugge, K. V.; Schader, E. E.; Moran, D. F. (1975), "Building damage in the San Fernando Valley", San Fernando, California, earthquake of 9 February 1971, Bulletin 196, California Division of Mines and Geology, pp. 323–353.

Further reading

edit- Bouchon, M. (1978). "A dynamic source model for the San Fernando earthquake". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 68 (6): 1555–1576. Bibcode:1978BuSSA..68.1555B. doi:10.1785/BSSA0680061555. S2CID 132403783.

- Gaudreau, É.; Hollingsworth, J.; Nissen, E.; Funning, G. (2022), "Complex 3-D surface deformation in the 1971 San Fernando, California earthquake reveals static and dynamic controls on off-fault deformation", Ess Open Archive ePrints, 105, Wiley, Bibcode:2022esoar.10511699G, doi:10.1002/essoar.10511699.1

External links

edit- San Fernando Earthquake – Southern California Earthquake Center

- Historic Earthquakes – San Fernando, California – United States Geological Survey

- California Geological Survey – About CSMIP – California Department of Conservation

- The International Seismological Centre has a bibliography and/or authoritative data for this event.

- Veterans Memorial Community Regional Park – Los Angeles County Department of Parks and Recreation

- Watch Disasters-Anatomy of Destruction (1987) on the Internet Archive