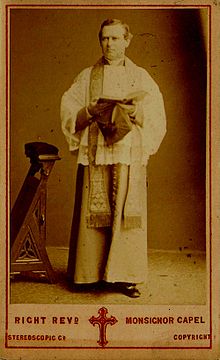

The Rt Rev. Thomas John Monsignor Capel (born 28 October 1836, Ireland – died 23 October 1911, Sacramento, California) was a senior-ranking Catholic priest.

Thomas Monsignor Capel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Title | Monsignor |

| Personal | |

| Born | 28 October 1836 Ireland |

| Died | 23 October 1911 (aged 74) Sacramento, California, U.S. |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

| Notable work(s) | A Reply to the Right Hon W E Gladstone’s ‘Political Expostulation’ (1874), Confession and Absolution (1884), Great Britain and Rome or Ought the Queen of England [sic] to Hold Diplomatic Relations with the Sovereign Pontiff (1884) |

| Military service | |

| Rank | Domestic Prelate of the Pope |

Early life

editBorn in either Waterford or Ardmore in Ireland,[1] by 1881 he gives his place of birth as Ramsgate in Kent;[2] this was either done for social reasons or represents a genuine error. His father John Capel was a Chief Boatman with the Coast Guard. His younger brother Arthur Joseph Capel was the father of the socialite Boy Capel.

In 1854 he helped to establish St Mary's Training College in Hammersmith and became its vice-principal where he remained until 1858 when ill health forced him to resign and go to France to recover. While in France he established the English Catholic Mission at Pau.

The Apostle to the Genteel

editOn his return to England he received into the Catholic Church the Marquis of Bute and many high-profile Anglicans. This led to Capel being satirised by Disraeli in his novel Lothair where he appears as Mgr Catesby. The identification of Thomas Capel as Catesby was fairly widespread as a letter of John Cashel Hoey to Archbishop Manning of 2 May 1870, the day of the book's publication, shows.[3] In 1873, possibly as a result of this and other conversions, he was created Domestic Prelate to the Pope.

Catholic University College

editIn 1874 Archbishop Manning established a Catholic University College in Kensington[4] and Mgr Capel was appointed Rector. The College was established to provide higher education to Catholics who were forbidden by Papal Decree to attend Oxford or Cambridge. The College faced problems from the outset, the principle one being that of finance; the theory was that the rich Catholic families who would benefit from the College would help to fund it during the first few years.[5] In practice however these families preferred to send their sons to Oxford or Cambridge and seek a dispensation for doing so. This situation was worsened by Mgr Capel's financial mismanagement[6] which left the College in debt and Mgr Capel bankrupt.

Diocesan Investigation

editOn 27 January 1879 a Commission of Investigation was set up[7] to investigate the following charges:

- To acts of criminal intercourse alleged to have taken place periodically between you (Capel) and Mrs Bellew from 1875 to September 1878

- To indecent liberties offered to Mrs Bellew's servant girl in the autumn of 1878

- To acts of criminal intercourse with Miss Mary Stourton in 1875, soon afterwards related by her to the Cardinal Archbishop. This relation she was believed to have subsequently retracted. But she had repeatedly since then affirmed ... that the letter which was supposed to be a retraction was written at your dictation and was untrue

- At the time when you took liberties, as alleged, with Mrs Bellew's servant, you were, as it is asserted, under the influence of liquor.[7]

The Commission met in February 1879 and began an exhaustive series of interviews with just about everyone involved however slightly with the case, the exception being Mrs Bellew who declined to attend.

Mgr Capel's defence attacked the character of Mrs Bellew[8] describing her as drunken, immoral and with a character that was "tarnished in no small degree".[8]

However the Commission found against Mgr Capel on the first three counts. Following this verdict Manning suspended Capel; he responded by appealing to Rome.

Kensington Confession Case

editIn August 1880 Mr Rutherford-Smith received an anonymous letter that said:

"I caution you as I have had to caution others against allowing your wife to go to luncheon so often at Monsignor Capel’s. Her friendship with Monsignor Capel is more than of an ordinary character and you had better come to London to sever the acquaintance. Cardinal Manning is already aware of it"[9]

He ignored this letter and a subsequent anonymous postcard, however on returning to London in November, and hearing a Catholic friend disparage Mgr Capel, Mr Rutherford-Smith decided to go to confession at the Pro-Cathedral of Our Lady of Victories in London. He made his confession to Fr Walter Robinson and during the confession mentioned the anonymous letters and his concerns regarding Mgr Capel. Fr Robinson asked to meet him outside of the confessional and they agreed to meet on the next Monday[10] at Fr Robinson's lodgings at 79 Abingdon Road. Up to this point the statements of Fr Robinson and Mr Rutherford-Smith agree, however in his statement of 26 March 1881 Mr Rutherford-Smith states that he believed that this conversation was also covered under the rules of the confessional whereas Fr Robinson said that he was given permission to discuss the matter with "any person or persons whom I might think fit for the sake of council".[10] In March Mr Rutherford-Smith formally charged Fr Robinson with breach of the confessional and in April the matter was placed into the hands of the Holy Office of the Inquisition and the Sacred Congregation de Propaganda Fide. Mgr Capel added further charges in a statement of 30 April[11] including accusing Fr Robinson of defamation of Mgr Capel, disobedience when Mgr Capel was Rector of the CUC and Fr Robinson its Censor, fabricating with the Mother Superior of the Convent of the Assumption Kensington Square accusations of Mgr Capel's drunkenness, encouraging the accusations of Lucy Stevens (c.f. the Diocesan Commission), and encouraging the resignation of Margaret Plues (Superintendent of St Anne’s Home) by suggesting that the Cardinal had "judged (Mgr Capel) guilty of serious faults against morality extending over many years" and that he was determined to "suspend (Mgr Capel) absolutely and that within a few weeks".[11] However, in May Mr Rutherford-Smith made a statement to Cardinal Manning[12] in which he not only retracted his complaint against Fr Robinson but also stated that it was Mgr Capel who had persuaded him to make the complaint. Furthermore, he suggested that the letter from Mrs Rutherford-Smith sent to Cardinal Manning was not written in her style although it was in her hand; he suggests that she copied something written by another. This accusation is supported by a letter of Fr Robinson to Cardinal Manning of 22 May.[13] By July a pamphlet had appeared giving the version of the case that condemned Fr Robinson; a copy was sent to the editor of the Weekly Register (an ultramontane Catholic paper based at 44 Catherine Street, Strand).[14] The increase in public interest in the case was of great concern to Manning.

Mgr Capel's Defence in Rome

editMgr Capel had appealed his condemnation in England to Propaganda Fide in Rome; this gave him advantages over Cardinal Manning. A letter received by Manning from Archbishop Michael Corrigan,[15] Archbishop of New York, which contains a letter to Corrigan by Archbishop John Lynch of Toronto highlights the problem. In the letter the Archbishop complained that any attempt to discipline a priest is foiled if that priest appeals to Rome; there, the letter continues, as he is the man on the spot his evidence has far more weight than that of his Bishop, who by the nature of his job is forced to remain in his diocese and can communicate with the authorities only by letter. Despite Manning's influence in Rome and the work of his agents there it was not possible to secure a conviction, although, despite Mgr Capel's various protestations to friends and supporters, he was not found innocent either. Manning informed Propaganda Fide and the Pope through Cardinal Howard that he would never grant to Mgr Capel faculties in England.

As a compromise it was decided that Mgr Capel should go to the United States; he was permitted to return to England to wind up his affairs and then must leave. Mgr Capel returned and Manning provided a large sum to settle his debts; the New York Times reports on the auction[16] at Cedar Villas.

Mgr Capel in America

editOn 30 July 1883 Mgr Capel arrived in New York[17] where he was feted and received much popular attention. By 1886 however things had started to go wrong for Mgr Capel; the New York Times of 4 October of that year published an article entitled "Mgr Capel's Downfall"[18] detailing accusations of drunkenness, inappropriate behaviour with women and an affair with the wife of Count Valesin a wealthy California rancher. A later article[19] suggests that the American clerical authorities had believed that Mgr Capel's problems in England were a result of financial mismanagement with the possibility of peculation but that they had "never before heard of his being connected with a woman". Cardinal Manning was informed on 10 July 1886[20] that the Pope had suspended Mgr Capel a divinis; this decree was never cancelled. Mgr Capel lived out the rest of his life at the McAulay Ranch in Sacramento California as tutor to Pio Valesin the son of Count Valesin. His death[21] was announced in the New York Times 23 October 1911.

Mgr Capel's guilt or innocence

editAmong the papers of the Westminster Diocesan Archive there are many records relating to the accusations directed at Mgr Capel;[22] these accusations are not limited to those that were examined by the Diocesan Commission or by Propaganda Fide. Mgr Capel is repeatedly accused of sexual irregularities some of which date back many years, although the accusations are made much later after rumours of the investigation have leaked, there are also many accusations of financial irregularity. The suggestion that Mgr Capel borrowed monies without any immediate possibility of repayment is clearly established but there are also reports of his offers to "invest" money for women[23] and failing to provide any return on this investment. Some of the cases against him are hampered by the changing stories of the women involved; Mary Stourton repeatedly changed her version of events although she did eventually support the accusation against Capel. This is entirely understandable; the social repercussions upon an unmarried woman of an admission of unchastity were dreadful and in some of Miss Stourton's later letters to Cardinal Manning it would appear that she had suffered a degree of social and familial ostracism.[citation needed]

References

edit- ^ 1851 Census (Class: HO107; Piece: 1635; Folio: 650; Page: 30; GSU roll: 193538.)

- ^ 1881 Census (Class: RG11; Piece: 23; Folio: 54; Page: 11; GSU roll: 1341005)

- ^ Westminster Diocesan Archive: Letter Regarding Political Issues, 2 May 1870: Ma.2/25/22

- ^ Westminster Diocesan Archive: Open Letter 21 November 1873: Ma.2/5/30

- ^ Westminster Diocesan Archive: Acta of the Bishops' Meetings, 9 April 1875: 34.5

- ^ Westminster Diocesan Archive: Papers on the Catholic University College in the Manning Collection: Ma.2/5

- ^ a b Westminster Diocesan Archive: Minutes of a Commission of Enquiry, 1879: Ma.2/3/166

- ^ a b Westminster Diocesan Archive: Mgr Capel's Defence: Ma.2/3/167

- ^ Westminster Diocesan Archive: Letter to Mgr Capel 26/3/1881: Ma.2/32/36

- ^ a b Westminster Diocesan Archive: Statement of Fr Robinson: Ma.2/32/6

- ^ a b Westminster Diocesan Archive: Accusation of Mgr Capel: Ma.2/32/43

- ^ Westminster Diocesan Archive: Statement of Mr Rutherford-Smith: Ma.2/32/48

- ^ Westminster Diocesan Archive: Letter of Fr Robinson: Ma.2/32/49

- ^ Westminster Diocesan Archive: Pamphlet regarding the Rutherford-Smith Case: Ma.2/32/51

- ^ Westminster Diocesan Archive: Letter Regarding Priestly Behaviour November 1883: Ma.2/31/27

- ^ https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1880/02/24/98889019.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1883/07/31/113296878.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1886/10/05/106302664.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1886/10/13/103988472.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Westminster Diocesan Archive: Letter Regarding Mgr Capel: Ma.2/3/540

- ^ https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1911/10/24/104879895.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Westminster Diocesan Archive: Manning Papers: Ma.2/3/1ff, Ma.2/32/1ff

- ^ Westminster Diocesan Archive: Letter Regarding Mgr Capel 7 March 1881: Ma.2/3/338

External links

edit- Media related to Thomas John Capel at Wikimedia Commons

- Works by Thomas John Capel at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Thomas John Capel at the Internet Archive

- Relationship to Arthur "Boy" Capel