Thomas d'Esterre Roberts (7 March 1893 – 28 February 1976) was an English Jesuit prelate. He was rector of St Francis Xavier’s, Liverpool, from 1935 to 1937. He was Archbishop of Bombay, India, from 1937 to 1950 but in practice did not exercise this role after 1946 when he absented himself from the post and left his Indian auxiliary bishop effectively in charge. In 1950 he was appointed titular Archbishop of Sugdaea, modern Sudak.

Thomas Monsignor Roberts | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop Archbishop Emeritus of Bombay | |

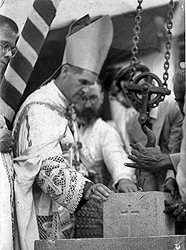

Roberts blessing the foundation stone of St. Peter's Church in Bandra | |

| Church | Roman Catholic Church |

| Archdiocese | Archdiocese of Bombay |

| Province | Bombay |

| Metropolis | Bombay |

| See | Bombay (emeritus) |

| Installed | 12 August 1937 |

| Term ended | 4 December 1950 |

| Predecessor | Joachim Lima SJ |

| Successor | Cardinal Valerian Gracias |

| Other post(s) | Titular Archbishop of Sugdaea |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 20 September 1925 |

| Consecration | 21 September 1937 by Archbishop Richard Joseph Downey |

| Rank | Archbishop |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Thomas d'Esterre Roberts 7 March 1893 Le Havre, France |

| Died | 28 February 1976 (aged 82) London, England |

| Buried | Kensal Green Cemetery 51°31′41″N 0°13′03″W / 51.5281°N 0.2174°W |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Residence | London |

| Parents | William d'Esterre Roberts (father) Clara Louise Roberts (mother) |

| Alma mater | College of St Elme Parkfield School, Liverpool St Francis Xavier's College Stonyhurst St Mary's Hall |

| Motto | Carior libertas (Latin) Freedom is more precious (English) |

| Styles of Thomas Roberts | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | The Most Reverend |

| Spoken style | Your Grace |

| Religious style | Monsignor |

Ordination history of Thomas Roberts | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

After leaving Bombay, not having a regular diocesan job, he dedicated himself to lecturing, writing, and the promotion of debate on controversial issues. He held that to be effective, authority had to be accepted, not imposed. This required that it be subject to open criticism, scrutiny and review, procedures which he felt were somewhat lacking in the governance of the Church. His refusal to sweep any question under the carpet at times unnerved some church authorities[1] and gained him a reputation in some Catholic circles as a "rogue bishop"[2] or a "maverick".[3] Although others applauded his challenging insights, the controversy obscured the significance of his work in Bombay.[4]

Early life

editThomas was born on 7 March 1893 in Le Havre, France, to Clara Louise Roberts and William d'Esterre Roberts, who were cousins. Thomas was the second son and seventh child of eventually nine children.[4] His father was from an Irish Protestant family of French Huguenot extraction.[3] Before Thomas was born, the family had lived in Liverpool, England,[5] then in the West Indies, where William did consular assistance before retiring in ill-health.[4] The family then settled in Le Havre where William became an export merchant. The family moved to Arcachon and Thomas went to the College of St Elme, a Dominican boarding school. The school had a nautical bias which had a lasting influence on Thomas's thought processes. In 1900 his father became a Roman Catholic.[6]

In 1901 his father died and the family moved back to Liverpool, where Thomas went to Parkfield School, a non-Catholic private school.[4] However, by 1908 he was considering the Catholic priesthood and asked to be transferred to St Francis Xavier's College a Jesuit school. On 7 September 1909, he entered the Jesuit noviciate at Manresa House, Roehampton.[3] He studied philosophy at Stonyhurst St Mary's Hall. In 1916 he was sent to Preston Catholic College for teaching practice. In 1922 he went to St Beuno's College, St Asaph, N Wales where he studied theology. He was ordained there on 20 September 1925, aged 32.[7]

After ordination, Roberts had spells teaching back at Preston College, then at Beaumont College, Old Windsor, Berkshire, where he set up a branch of the Catholic Evidence Guild, with 33 speakers at pitches in four dioceses. His tertianship was at Paray-le-Monial in the Saône-et-Loire department, followed by another six years, 1929-1935, teaching at Preston College. In early 1935 he became the youngest Jesuit rector in the country when he was appointed rector of St Francis Xavier's, Liverpool.[a] St Francis Xavier's was one of the largest parishes in England, in an inner-city area, with high unemployment and clashes between Catholics from Southern Ireland and Protestants from Northern Ireland.[8]

On 3 August 1937 he learned he had been named Archbishop of Bombay when a journalist from the Liverpool Post asked him for a comment on his appointment.[4] Years later, in retirement, he insisted his appointment had resulted from a bureaucratic blunder on the part of a Vatican official.[9]

Archbishop of Bombay

editBombay was ceded by the Portuguese to England in 1661 as part of the dowry of Catherine of Braganza on her marriage to King Charles II. Ever since then there had been difficulties between the Portuguese on the one side and the English and the Vatican on the other side over the administration of the Catholic Church in India in general and the appointment of the Archbishop of Bombay in particular. The Vatican had set up the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (known for short by the Latin word Propaganda) to be responsible for missionary areas such as India. However, the Portuguese claimed that the Padroado (by which the Vatican had, beginning in the 15th century, delegated to the kings of Portugal the administration of local churches in the Portuguese sphere of influence) gave them that right in those territories in perpetuity even where Portugal had ceded control. In 1928 it was agreed under a concordat between the Vatican and the English and Portuguese Catholic hierarchies that the post of Archbishop of Bombay would be held alternately by a Portuguese and an English Jesuit. There was no provision for an Indian. The first ordinary appointed under the concordat was a Portuguese, Archbishop Joachim Lima, S.J. He died on 21 July 1936 and Pope Pius XI appointed Roberts on 12 August 1937.[10][11]

Roberts received his episcopal consecration on 21 September 1937 from the Archbishop of Liverpool, Richard Downey. Co-consecrators were the Archbishop of Cardiff, Francis Mostyn, who had ordained Roberts, and the Vicar General of Liverpool archdiocese, Robert Dobson.[5] Over 100 priests attended and the congregation of over 1000 spilled out into the street for a service which lasted over three hours, a tribute to someone who 2½ years previously was an obscure lower form master at Preston College.[12]

As his episcopal motto Roberts chose Carior libertas, "Freedom is more precious", from the motto of the Irish branch of his family, the d'Esterres, Patria cara, carior libertas: "My country is precious, but freedom is more precious".[12]

Shortly afterwards, Roberts left Liverpool for Bombay. On the way, he spent two weeks in Lisbon in an attempt to lessen the tensions that still existed between the two hierarchies.[13] He saw the Prime Minister, Dr Salazar, and Cardinal Cerejeira, the first time a non-Portuguese archbishop had made contact with the Portuguese authorities.[3] He arrived in Bombay on 1 December 1937.[14]

The Catholic archdiocese of Bombay was the largest in India, and stretched from Baroda (modern name Vadodara), Gujarat state, about 300 miles north of Bombay, to the village of Korlai, in Maharashtra state, about 50 miles south. There were 68 parishes with 140,000 members predominantly among the poorer sector. There were 121 secular clergy, 66 Jesuits, and three Salesians. It had a college of higher education, Xavier’s, the largest in Bombay and later to become a constituent of Bombay University, 25 high schools and 88 middle and primary schools.[15]

Overlapping and cutting across the Padroado/Propaganda division was a further division based on place of origin: indigenous Bombay Indians, immigrants from Catholic centres such as Goa, Mangalore, Madras, and Malabar, as well as Europeans and Anglo-Indians. All were deeply suspicious and jealous of each other.[16] Roberts exploited his relationship-building with the Portuguese by rationalising the parish structures with the help of the Portuguese Consul General.[13]

Particularly controversial was his decision to abolish the parish of Our Lady of Esperance[b] at Bhuleshwar. This had been the cathedral parish since 1887 but the church was a vast, expensive to maintain building in an area by then devoid of Catholics.[17] He sold the land and used the proceeds to build churches in the suburbs where the Catholics then lived. He adopted the Church of the Holy Name, the parish church on the harbour, as his pro-cathedral, later to become the Cathedral of the Holy Name, Mumbai. He broke with tradition by appointing not a Jesuit but a Goan, Fr Valerian Gracias, as its first secular rector.[18] This was part of a policy of steady Indianisation of the clergy, which Roberts adopted with the blessing of his Jesuit superiors, and which was virtually complete in the archdiocese by 1945.[19]

Roberts worked on improving the unity of the archdiocese by a series of letters to the children of his diocese, published in The Examiner, his diocesan newspaper.[3][c] He put in place a wide range of social services particularly for the poor, orphans, and prostitutes much of it paid for by fund-raising carried out by the children in response to his appeals to them through The Examiner, many catalogued in From the Bridge. He set up centres where seamen could stay while in port. In 1941 he overcame stiff opposition orchestrated by Bombay University's Professor of Economics and member of the Senate K. T. Shah and established the university's Sophia College for women.[21][4] This was for Christians and non-Christians alike. He later had to overcome attempts by Shah in 1942 and again in 1943 to have the college disaffiliated from the university. The senate rejected the 1942 proposal but passed the 1943 proposal. After mass protests in Bombay the decision was overturned by the Government of Bombay which had the final say on Senate decisions.[22]

In 1939 Gandhi's Congress Party proposed to introduce prohibition. Roberts, in an address to the Rotary Club, subsequently broadcast on All India Radio, argued that it would not succeed unless the Indian people were solidly behind it, which he was unconvinced was the case. Although his view received wide approval, it brought him into conflict with Gandhi, who drew a parallel between the state provision of drinking facilities and the state provision of women for prostitution.[23]

During World War II Roberts was appointed Bishop Delegate to H.M. Armed Forces in the Indian and South East Asia Commands. As his American counterpart was unable to fly he also ministered to American service personnel. This involved flights of over 2000 miles (each way) in service planes to where the troops were, in Assam, Burma and as far as the Chinese border, and meant he could be away for months at a time.[24][25] This was not without risk, and he was involved in two crash-landings, one when the undercarriage jammed, the other when an engine failed in mid-flight. For this work he received the Kaisar-i-Hind gold medal in the 1946 Birthday Honours, probably its last recipient.[26] There was a particular problem with the presence in India of religious communities from the Axis powers, particularly German and Italian Catholic nuns. The British colonial rulers invited Roberts, as the only British prelate in India, to sit on the commission set up to deal with them.[27]

With India moving towards independence, Roberts saw that it would be untenable to keep the system whereby Indian Catholics were governed alternately by a British and a Portuguese archbishop. In May 1945 he visited Pope Pius XII in Rome and proposed that the 1928 concordat be terminated, followed by his demitting his post as archbishop. If he simply resigned he would be succeeded by a Portuguese, not an Indian. To get round this, Roberts planned to appoint an Indian auxiliary bishop, ostensively with a view to proving that Indians were perfectly capable of running their own affairs. An auxiliary bishop had no right of succession (so the Portuguese could not object) but might in practice succeed, especially once India was independent. While accepting Roberts's plan in principle, the Pope asked for an explicit undertaking from Roberts that he would not drop the title of Archbishop of Bombay. Roberts returned to India to manage the transfer of his responsibilities to the auxiliary bishop. On 16 May 1946 Gracias was appointed and Roberts consecrated him on 29 June 1946.[28] Roberts then left for England on an oil tanker, the British Aviator.[29]

So long as the Portuguese insisted on their rights, Roberts could neither resign nor drop his title. As a result he could not take up another permanent appointment. His arrangement with Pius XII required him to be out of Bombay (at sea or in America) to leave any possible successor a free hand, but with the possibility of returning to Bombay if necessary.[30] Thanks to some friends in the British Tanker Company, part of what is now BP, he spent a period as a temporary chaplain of the Apostleship of the Sea, working on oil tankers. He spent some time in India again in 1947/1948 after being ordered back by the Vatican by mistake. He left again in August 1948 by signing on as a crew member of an oil tanker in Bombay harbour, leaving his auxiliary in complete charge.[31]

Eventually Prime Minister Nehru of the now Republic of India called for an end to the remains of colonisation. Padroado and the 1928 Concordat were terminated on 18 July 1950[32] and Roberts's resignation was finally accepted in December 1950. He was succeeded by Gracias, later to become the first Indian cardinal.[33]

Titular Archbishop of Sugdaea

editOn resignation, Roberts was appointed titular Archbishop of Sugdaea in Crimea (modern Sudak).[2] His resignation was announced in L'Osservatore Romano as on grounds of ill health, perhaps because at that time resignations of bishops were unusual except on grounds of senility. However, the announcement that he was ill did not help Roberts in his quest for a new position, even a temporary one.[32] Talk of other full-time episcopal appointments perhaps in Guyana or the West Indies came to nothing.[3] He resumed life as a Jesuit in the English province and dedicated himself to lecturing and writing. He gave retreats for a time at Loyola Hall, Rainhill, Merseyside. In 1951 he became Spiritual Father at Campion Hall, University of Oxford. From 1954 he was based at the Mount Street Jesuit Centre, London. He travelled a great deal, visiting Jesuit institutions and giving retreats in Scotland, England, Germany, and the USA, including periods on the staff of Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington, from May 1958 to September 1959 and for another six months in 1960. He retained his war-time connection with the US military, visiting US troops in Allied-occupied Germany.[25] He also twice visited Bombay at the invitation of Cardinal Gracias.[34]

He promoted debate on issues about which he felt strongly despite their discussion being unpopular with many in the Catholic hierarchy: how authority was exercised in the church and the right, indeed duty, to ask questions of those in authority; the importance of exercising an informed conscience; the Church's stance on contraception[3] and peace, nuclear war and the right to conscientious objection.[35]

Writings on authority

editIn 1954 he wrote Black Popes: Authority its Use and Abuse[d][e] in which he argued that "blind obedience" was harmful and that effective authority requires responsibility, openness, and unhindered two-way communication. Failing this, authority is liable to become abuse. Because of the danger of abuse, obedience to authority should not be out of fear but "intelligent" i.e. questioning and reasoned: he drew an analogy to the non-Catholic's appeal to conscience.

He also criticised the bureaucratic process in the church's marital courts and called for greater involvement of the laity in church affairs.[37]

In April 1961 he followed this up with "Naked Power: Authority in the Church Today", a paper delivered to a symposium on Problems of Authority held at the Abbey of Our Lady of Bec, Normandy.[38] In a quote from Black Popes he took issue with the discouragement of criticism to higher authority in the church: such questioning was regarded as treason,[39] heresy or rebellion,[40] whereas Roberts regarded it as a duty.[41] He pointed out that there were many instances in the Acts of the Apostles of open disagreements between Christ's disciples.[42] He went on to criticise ecclesiastical proceedings under Canon Law. These could be done in secret with anonymous witnesses, without the accused being told the charges, without a hearing and with no acknowledgement of any defence; furthermore, those carrying them out could have no training except spiritual[43] and little knowledge or experience of the world outside the religious.[42]

Association with peace movement

editRoberts was not a pacifist: he believed in a just war and the right to self-defence against those who were "mad or bad".[44] He was in favour of World War I and was embarrassed that his being a clerical student exempted him from call-up.[45] While supporting the right to conscientious objection, his position, explained while Archbishop of Bombay in an interview broadcast on All India Radio and rebroadcast by the BBC, was "a point must be reached when the choice lay between repelling violence by violence or of handing over our children to be indoctrinated to violence".[46] However, the advent of nuclear weapons, which could indiscriminately affect non-combatant countries, caused him to questioned the morality of a future war.[47]

While chaplain to the forces in India, Roberts had seen at first hand the human misery and material loss caused by war. He began to associate himself with peace groups – the Quakers, the Fellowship of Reconciliation, and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament ("CND") – and became a trustee of Amnesty International.[48] In 1959, when lecturing at Gonzaga University, he took part in an inter-faith conference in the city on peace, fundamental human rights and the morality (or otherwise) of governments involving citizens wholesale in nuclear war.[49] He became a sponsor of Pax, a Catholic society for peace which subsequently merged with Pax Christi, and in October of that year he addressed a Pax meeting held at Spode House (also known as Hawkesyard Hall).[f][35]

He refused to join the Committee of 100, a British anti-war group, as he did not believe in civil disobedience. He did, however, agree to appear for the defence at the trial in 1962 of the Wethersfield Six who were prosecuted after 5,000 protesters occupied the runway at an RAF base to prevent planes taking off. In the event, the key question that he was asked by defence counsel on whether nuclear weapons were immoral was ruled of out of order by the judge.[50]

In July 1963, Roberts published an article in Continuum, an American Catholic review, entitled "The Arms Race and Vatican II".[g] In it he developed Pope John XXIII's statement on nuclear non-proliferation in his 11 April 1963 encyclical On Establishing Universal Peace in Truth, Justice, Charity and Liberty (Pacem in Terris) that " … if any government does not acknowledge the rights of man, or violates them, it not only fails in its duty, but its orders completely lack juridical force."[52] Given that in a nuclear war there was likely to be accidental destruction of non-participating countries Roberts concluded that nuclear warfare was not morally lawful.

In a "question and answer" session with the American (Catholic) Pax society (published in their autumn 1964 newsletter, Peace)[53] Roberts said that most bishops on both sides during the recent war justified supporting their governments on grounds of obedience to the authority of the state. Noting that this was rejected at the Nuremberg trials Roberts argued that the "individual has a fundamental right to freely follow his own conscience" and that "conscientious abstention" (his preferred phrase) was a human right.

In March 1968 Roberts joined a small group praying outside the American Embassy in London for an end to the Vietnam War and for the right of conscientious objection. He later accompanied them to a meeting in the embassy. This attracted some attention in the press because earlier in the month 10,000 had rallied in Trafalgar Square and their march on the embassy had turned into a riot with 86 injured and 200 arrests.[54]

Delation to Rome

editIn May 1960, while he was still at Gonzaga University, Roberts first heard of charges against him in a letter from Archbishop O'Hara, then Apostolic Delegate to Great Britain, in London. The process was described as "delation",[55] an archaic word meaning the secret criticising of someone to church authorities.[56]

He was accused by unnamed bishops and archbishops of addressing a meeting of Pax in October 1959 despite Cardinal Griffin, in 1955, banning such active association after Pax attacked the work of the Catholic Truth Society. O'Hara also accused him of revealing, at that Pax conference, "the secrets of the [Second Vatican] Council" in that he had disclosed his reply to a request from Cardinal Tardini for suggestions for the agenda.[h]

O'Hara also alleged that Roberts had written a letter published in The Universe attacking the English bishops on their implementation of the Pope's wishes on sacred music and the liturgy.

O'Hara then quoted in full a letter from Cardinal Mimmi, Secretary of the Sacred Consistorial Congregation for Bishops which said in essence that Roberts should keep silent in future. O'Hara had already sent copies of the proceedings to four curial Roman departments[i] and to the Secretary General of the Jesuits.

In reply, Roberts refuted the charges and complained that the allegations had been heard, judgement given and punitive action taken before the accused even knew he had been charged.

On the specific charges, he was unaware of any ban on Pax by Griffin, and the relevant conference at Spode, "an irreproachable venue", was advertised in Catholic newspapers. His letter to Tardini did not suggest what the Council might discuss. He had merely asked for an extra-conciliar examination of an issue that troubled the consciences of many people, namely personal decisions about participation in nuclear war.[j] Finally, Roberts challenged O'Hara to produce the letter he was supposed to have written to The Universe attacking the English hierarchy.[k]

Roberts said that he would ask the Vatican for a full investigation of the charges. If found true he would accept the punishment; if false he would expect his innocence to be given as much publicity as the allegations of guilt had already been given without his knowledge.

Three months later, O'Hara wrote again to tell Roberts that his book Black Popes (published 6 years previously) had been discussed at a plenary session of the Holy Office. The Holy Office had issued a decree that "scandalous" portions of the book be omitted or modified in subsequent editions and asked for confirmation of execution of the decree. Roberts wrote back on 5 September 1960 to say that there was no question of new editions at present. On his informing his publishers they had asked which passages had caused offence: no detail had been given other than that the offending material was in chapters 6 and 7. These dealt respectively with the succession and controversial reign of Pope Boniface VIII (1294-1303)[l] and the suppression of the Society of Jesus by Pope Clement XIV for political reasons in 1773. Roberts pointed out that the condemnation of Black Popes could embarrass the Pope as the book's Spanish edition had an imprimatur and there had been many positive reviews of the book in the Catholic press.[m]

Roberts posited that bishops owed to the church a standard of justice higher than any in the world,[60] for example England where justice had to be "done and seen to be done". In order to illustrate his case to the Pope, he obtained the opinions of two experienced lawyers, including an authority on criminal libel, as to the likely outcome of a hypothetical referral to the English courts. He intended then to use his own case as a good example of what was wrong with proceedings under Canon Law. Both lawyers independently advised that the actions of Archbishop O'Hara in the letter of May 1960 and the condemnation of passages in Black Popes would, in the English courts, be regarded as defamatory. Although O'Hara could claim that his communications were covered by privilege, that claim would be defeated because there was evidence, for example the absence of due process, of malice on the part of O'Hara. This would render O'Hara liable in an action for libel and could give rise to a criminal prosecution.

Roberts saw Pope John XXIII on 6 December 1960. The Pope undertook to open an enquiry into the affair. Despite sending reminders Roberts heard nothing further; eventually Cardinal Cicognani, Cardinal Secretary of State and President of the Co-ordinating Commission of the Vatican Council told Roberts in December 1962 that Roberts's hearing nothing meant vindication and there would be no bar to his attending the Council. The Pope, who had been seriously ill for some time, died on 3 June 1963. O'Hara died a month later. Roberts let the matter rest but he remained troubled by it because it was a matter of truth and conscience.[61][4][3]

Position on contraception

editRoberts gave the inaugural address to the Catholic Medical Guild of St Luke, Bombay, which he had set up in 1938. In this he extolled them to follow "Christian tradition" and "not [to] restrict birth artificially". He went on to criticise the 1930 Lambeth Conference for its abandonment of its previous stance against contraception.[n] [62]

In the early 1960s, questions began to be asked by Cardinal Suenens and by many others in the Catholic Church about the appropriateness of its ban on contraception.[63] In order to forestall mass discussion of the topic at the Second Vatican Council, Pope John XXIII set up a Pontifical Commission on Birth Control in 1963.[64]

Informed by his nine years in India, with its high birth rates and poverty, Roberts, too, had come to question the continued appropriateness of the Catholic traditional approach. He gave an interview to Michael de la Bédoyère for publication in the April 1964 edition of the latter’s magazine Search. In this he admitted that could not understand the Catholic Church's position that contraception was "unethical". He could not see how the position taken by the 1958 Lambeth Conference[o] could be refuted by reason alone and said that if he were not bound by the Church's ruling he would have accepted it.[66]

On 7 May 1964, English bishops led by Archbishop (later Cardinal) Heenan published in the Sunday Times a statement quoting Pope Pius XI's encyclical letter Christian Marriage, 1930, (Casti connubii) that contraception was "against the laws of God and of nature" and that the church "cannot change God's law". In a thinly veiled attack on Roberts they warned of "false leaders". Roberts was then in Chicago. The London Evening Standard drew his attention to the article and asked for a response which it would publish. In it Roberts denied the claim of the English hierarchy that he was "leading people astray". He merely represented the views of many in the church in calling for a review. After all, the Church had changed its mind historically about what was and what was not sinful.[67][68]

Roberts wrote an expanded version of the Search paper which was published later in 1964 in Objections to Roman Catholicism alongside his Continuum paper on war. At the same time he contributed the introduction to a symposium on Contraception and Holiness: the Catholic Predicament. Roberts argued from his experience seeing the poverty and malnutrition caused by the population explosion in India on the back of improved medical facilities and the failure of the Indian government's attempt to promote the rhythm method. He was also conscious of the divergent attitudes to this question taken by Christian missionaries in India from Catholic and Protestant traditions yet the term "natural law" implied something that should be universally recognised. He intended to say so at the Second Vatican Council, which was then in progress. He would urge the Council, as an ecumenical council, to consult widely but specifically to include married couples in order to re-examine the question with a view to clarifying this "natural law" and to justifying its case by logical reasoning.[69]

In practice, discussion at the Council was stifled when the Pope, by now John XXIII's successor, Paul VI, announced that the matter was reserved to him.[70] In 1966, after the end of Vatican II but before the Commission reported, during which there was a feeling in the Catholic laity that there might shortly be a relaxation of the ban on contraception, Roberts wrote Quaker Marriage: A Dialogue between Conscience and Coercion. This was a case study about an imaginary couple, the man a devout Quaker, the woman a devout Catholic, who had been told after the difficult birth of their first child that future pregnancies were likely to be fatal for the wife. The paper explored their relationship with each other and with their traditionally-minded parish priest and his more liberal curate. It was published in the symposium The Future of Catholic Christianity.

The Pontifical Commission reported after the close of the Council, a large majority recommending that the ban on artificial birth control be lifted. This was rejected by the Pope, who accepted a minority report. This admitted that there was no argument in reason why contraception should be condemned, but recommended that the Pope use his authority to maintain the status quo. On 29 July 1968 the Pope issued the encyclical Humanae Vitae reaffirming the ban.[64] Roberts was reported in the New York Times as having said that the encyclical "flies in the face of reality" and that Catholics no longer raised the use of birth control in the confessional.[71]

When asked to, Roberts continued to speak on contraception, but was careful never to undermine the papacy or hierarchy tasked with promulgation of the ruling. He stuck to the facts: how the decision was made, the views of bishops in various parts of the world, the views of non-Catholic Christians and of non-Christians,[p] that the encyclical was not subject to "infallibility", and that popes had made mistakes in the past.[72]

Involvement with Second Vatican Council

editRoberts attended the Second Vatican Council ("Vatican II"), held from 1962 to 1965, but he never managed to speak on the council floor.[3] In the second period (autumn 1963), Roberts submitted a paper asking for reform in ecclesiastical procedures affecting marriage and divorce which he claimed were cruel and unnecessarily drawn out.[2] In the third period (autumn 1964), in the session on "The Church in the Modern World", Roberts submitted a shortened version of his Continuum paper and asked for Catholic support for conscientious objection to wars that were immoral. He cited the recently publicised case of Franz Jägerstätter executed by the Germans in World War II.[35] He was not called to speak and conscientious objection and the question of obedience that made World War II possible were not discussed.[73] The statement which eventually emerged in Gaudium et Spes fell short of a demand for unilateral nuclear disarmament but left little scope for any real conviction that the use of nuclear weapons could be justified.[1]

This was followed by a session on "Marriage and the Family". Roberts applied to speak, submitting a shortened version of his Objections paper on contraception.[74] He was not called to speak, but the matter was taken up by other bishops, including Cardinal Suenens who warned "let us avoid a new Galileo case".[75] Discussion was curtailed pending the report of the Pontifical Commission.

Not being called to speak at the Council sessions, Roberts took every opportunity to make his views known outside them, for example in press conferences.[76] Referring to a discussion in Council on the guilt of the Jews for deicide, he took the opportunity to return to his theme of the Church's discouragement of criticism: "It is so plain that the guilt lay not with the Jewish people, but with the Jewish priestly establishment, that it seems legitimate to wonder whether the refusal to face up to this may not be a subconscious reluctance to face up to the analogy in the Church today".[77]

Roberts's attitude to women

editRoberts's stance on women was that they must not be treated as second-class citizens.[78]

He founded Bombay University's Sophia College for women in 1941, 6 years before women were admitted as full members of Cambridge University in England.[79]

When Vatican II started women were not admitted (all observers had to be male). When the Quaker observer at the Council, Dr Ullmann, died in August 1963, Roberts suggested that his widow be invited to attend in his stead, but this was not possible. At a press conference he gave on 22 October 1963, during the 2nd session, he complained that "There are whole classes of Catholics unrepresented at this Council: nuns and other women." Women were admitted as observers from the 3rd session (September 1964) onwards.[80]

In a 1964 interview in the New York Catholic magazine Jubilee Roberts complained that the church's attitude to women had hardly changed since Old Testament times. He pointed out that the views of the early Church Fathers reflected the views of their time, namely that women were little more than animals and that procreation was the sole purpose of sex in marriage. He went on to criticise professors in seminaries for not emphasising to seminarians that such views were no longer valid.[81]

In his introduction to Contraception and Holiness, written before the composition of the Pontifical Commission on Birth Control was made public, Roberts echoed Cardinal Suenens's call for a special commission "composed of laymen and clergy, men and women [emphasis in original] to study the problem in collaboration with the [Pontifical Commission]."[82]

In the run-up to the 1971 Synod of Bishops, a Belgian Dominican nun, Sr Buisseret, wrote an open letter to the bishops calling for bishops to be able "to confer on qualified women the exercise of certain ministries hitherto reserved to men, not excluding the priesthood". This would be "on an experimental basis" and "in certain limited areas of the church": she instanced missionary areas where priests were in short supply.[83] She asked for those who agreed with her proposal to write to her indicating their support. Roberts wrote that his experience as a Jesuit priest for 48 [sic][q] years and an archbishop for 34 years led him to "endorse her suggestion without reserve."[84][78]

Roberts's unconventionality

editObedience was an obsession for Roberts and he took his vow of poverty literally, eschewing 1st class travel and wearing handed-down clothes.[85] At the Vatican Council, he stayed in a tiny room and would often receive visitors in a pyjama top and aged shawl over black trousers.[86]

He disliked ecclesiastical pomp and advocated simplification. He particularly disliked Pontifical High Mass, where he felt that the focus of attention was on the bishop instead of on the service. He disliked the term "Your Grace" preferring to be called "Father". He disliked fancy lace vestments, likening them to women's underwear, and kept his episcopal ring in his back pocket to discourage people from feeling they were expected to kiss it. He disliked St Peter's Basilica in Rome and told his biographer, Hurn, "I never feel altogether comfortable in St Peter's. I keep remembering that it was largely built from the sale of indulgences." These attitudes gave him an affinity with Low Church members.[87]

His experience of working with non-Christian religions in India led him to promote friendships with non-Catholics generally and rapprochement with other Christian denominations in particular.[88] By invitation from Archbishop and Mrs Ramsey, he became the first Roman Catholic prelate to dine at Lambeth Palace since Cardinal Pole, the last Roman Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury, in the 16th century.[89]

He advised Pope Pius XII against dogmatically defining the Assumption of Mary in 1950[9] and long before Vatican II he was in favour of a relaxation of the ban on cremation,[90] advocated involvement of the laity in church affairs, and associated himself with the Christian anti-racism movement.[91]

Relationship with the Hierarchy

editRoberts was unswervingly loyal to the church, but to him loyalty did not include passive acquiescence in the status quo, which he saw as laziness if not cowardice.[92] His unconventional views, his willingness to challenge authority, and his association with non-Catholic Christians, unsettled some in the Catholic Hierarchy, who shunned him, blocked his activities, and on occasion actively attacked him.[4]

He was asked to lead the prayers at an interdenominational CND and Christian Action meeting in Trafalgar Square on Remembrance Sunday, 12 November 1961, but Cardinal Godfrey forbade him from doing so.[93]

In 1964, the Fellowship of Reconciliation asked him to make a lecture tour of the US and he took part in many lectures across the US and Canada. However, Cardinal McIntyre of Los Angeles and Bishop Furey of San Diego forbade him from speaking in their dioceses.[r][95]

When the 38th International Eucharistic Congress was held in Bombay in November 1964 and attended by Pope Paul VI, Cardinal Gracias invited Roberts to be his guest, but then shunned him and excluded him from meeting the Pope. Much was made of the fact that Gracias was the first Indian cardinal but Roberts's role in his career was not acknowledged.[96]

In January 1965 Roberts was invited to be principal speaker at a lunch, organised by Foyles booksellers at The Dorchester, to promote the book Objections to Roman Catholicism, which had been published the previous October. Three days before the lunch he received a note suggesting that he withdraw, which he did. This caused speculation in the press as to who had written the note: Roberts considered himself under a vow of silence. Speculation increased when Archbishop Heenan declined to give an "on the record" comment.[97] On the eve of the lunch, Fr Terence Corrigan, head of the Jesuits in England, said that he had asked Roberts to "reconsider" his invitation to speak as he felt that the attendance of a well known Jesuit figure on such an occasion would have suggested that the society was somehow in a dispute with the English Catholic hierarchy.[98] Roberts then issued a statement which was read at the lunch in which he said, "… neither the book as a whole, nor my contribution to it, was intended to be a move against the English Roman Catholic hierarchy. Its purpose was more vital – to air problems which were of intimate concern to thousands of Catholics, and, indeed, to the whole world. I am glad that the book is succeeding in its task."[99]

In 1967, in a talk Roberts was giving at the University of Cambridge on freedom of conscience, Rev. Joseph Christie, acting chaplain for Roman Catholic students, interrupted the talk and accused Roberts of heresy.[2]

In 1968, Roberts was asked to give a talk to the Catholic Society at the University of St Andrews. Aware that there was likely to be unfounded criticism of his talk and misrepresentation of what he said he was very careful to stick to facts, particularly when asked directly for his view on the Scottish bishops' statement on the encyclical Humanae Vitae. Nevertheless, the university chaplain, Fr Ian Gillan, intervened and accused him of publicly insulting the Scottish hierarchy and of encouraging his listeners not to follow their bishops, charges refuted by the chairman of the meeting, Miss Isabel Mageniss.[100]

Despite his being called a "rogue bishop" or a "maverick" by some, others, particularly among the Jesuits, thought highly enough of him to devote the entire March 1973 issue of The Month to a symposium entitled "Tribute to Archbishop Roberts on his 80th Birthday". As well as some biographical notes on his achievements in Bombay, this included articles discussing and developing his challenging ideas, with one author calling him the 'courageous and inspiring churchman we honour in these pages'.[101]

He was also in great demand from the laity who went to him for advice and encouragement, particularly in distress.[3]

Death

editAfter a month in hospital in London, Roberts died of a heart attack on 28 February 1976.[33]

At his requiem mass at the Church of the Immaculate Conception, Farm Street, on 8 March, Archbishop Heim, Apostolic Delegate, was chief celebrant and 200 priests concelebrated, including the head of Jesuits in Great Britain. Bishop Butler preached the homily.[1]

Roberts was buried at Kensal Green Cemetery.[1]

Selected writings

edit- From the Bridge (with Three Reports to the Bridge). Bombay Examiner Press. 1939.

- Black Popes. Authority: Its Use and Abuse. Sheed and Ward. 1954.

- Diary of Bathsheeba edited by Archbishop T. D. Roberts, S.J. Sands. 1970.

- Contributions

- Walter, Stein, ed. (1961). "Foreword". Nuclear Weapons and Christian Conscience. Merlin Press.

- Todd, John M., ed. (1962). "Naked Power: Authority in the Church Today". Problems of Authority. Darton, Longman and Todd.

- De La Bédoyère, Michael, ed. (1964). "Questions to the Vatican Council: Contraception and War". Objections to Roman Catholicism. Constable and Co.

- "Introduction". Contraception and Holiness: The Catholic Predicament. Herder and Herder. 1964.

- De La Bédoyère, Michael, ed. (1966). "Quaker Marriage: A Dialogue between Conscience and Coercion". The Future of Catholic Christianity. J. B. Lippincott Company.

Notes

edit- ^ Coincidentally, his parents had married there.[5]

- ^ Also known as Nossa Senhora da Esperança, easily confused with others with this name of which there were many in India.

- ^ Many of these were later published in From the Bridge, the title of which was a reference to Roberts's nautical interests.[20]

- ^ "Black Pope" is a popular title given to the General of the Society of Jesus.

- ^ Kirkus Reviews thought he wrote in response to American Freedom and Catholic Power (1949) by Paul Blanshard.[36]

- ^ Spode House, Armitage, near Rugeley, Staffordshire, was the first Roman Catholic conference centre in Great Britain.

- ^ The article was re-printed in the book Objections to Roman Catholicism.[51]

- ^ Tardini, as Cardinal Secretary of State, had written to all bishops soliciting items for discussion at the Council

- ^ These were the Consistorial Congregation, the Holy Office, the Congregation of Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs, and the Congregation of Religious.[57]

- ^ In any case, while communications from the Vatican were confidential, bishops were free to publicise their replies and many did, including Roberts at the Spode conference.

- ^ The point was that he had written no such letter.

- ^ Roberts was later to devote a chapter of his book Diary of Bathsheeba to criticising Boniface's actions.[58]

- ^ Yves Congar, who became a key figure at the Second Vatican Council, noted in his diary in 1961 that Roberts had not been ordered to withdraw his criticisms of contemporary church governance, "and those are the pages to which he himself is most attached".[59]

- ^ See Resolution 15, The Lambeth Conference, Resolutions Archive from 1930 https://www.anglicancommunion.org/media/127734/1930.pdf

- ^ This had laid responsibility for deciding the number and frequency of children on the consciences of parents in the context of the resources of the family and the needs of society as a whole.[65]

- ^ The encyclical was addressed "to all men of good will".

- ^ Actually 46

- ^ In a 1963 decree "On the Powers and Privileges Granted to Bishops", Pope Paul VI held that a bishop is free "To preach the word of God everywhere in the world, unless a local [bishop] expressly disapproves".[94]

References

edit- ^ a b c d "Obituary: Archbishop Thomas Roberts", Kay, Hugh, Letters and Notices, Volume 81, No 371, Society of Jesus, November 1976

- ^ a b c d "Archbishop Roberts Dies at 82; 'Rogue Bishop' Served Bombay". New York Times. 29 February 1976. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hebblethwaite, Peter (6 March 1976). "Archbishop Roberts". The Tablet. Archived from the original on 21 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Blake, Robert; Nicholls, C.S., eds. (23 September 2004). "Roberts, Thomas D'Esterre (1893–1976)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography 1971-1980. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198652089.

- ^ a b c "Mother and Sister See Archbishop Roberts Consecrated". Catholic Times. 24 September 1937.

- ^ Hurn p 9

- ^ Hurn pp 10-11

- ^ Hurn pp 11-12

- ^ a b Kaiser, Robert Blair (2002). Clerical Error: A True Story. A&C Black. p. 121. ISBN 9780826413840. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ Hurn pp 29-33

- ^ Black Popes, p viii

- ^ a b "Crowds at Liverpool Ceremony". Catholic Herald. 24 September 1937.

- ^ a b "Farewell to Archbishop Roberts". The [Bombay] Examiner. 6 February 1954.

- ^ From the Bridge, pp1,7

- ^ Aguiar, p 69

- ^ Aguiar, p 68

- ^ Aguiar, p 78

- ^ Hurn p 36

- ^ Hurn p 42

- ^ Hurn pp 37-38

- ^ University of Mumbai, list of colleges, http://mu.ac.in/portal/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Updated-All-College-List-with-Course-Detailss.pdf

- ^ Aguiar, pp 78-79

- ^ Aguiar, p 75, quoting from Gandhi's publication Harijan

- ^ Aguiar, p 80

- ^ a b "Archbishop Thomas d'Esterre Roberts, S.J. to Open Religion in Life Series" (Press release). University of Dayton. 13 October 1969. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ "No. 37598". The London Gazette (Supplement). 13 June 1946. p. 2797.

- ^ Hurn pp 42-44

- ^ Hurn pp 44-47

- ^ Aguiar, p 81

- ^ Statement by Roberts, as a postscript to Aguiar, p 81

- ^ Hurn pp 47-48

- ^ a b Hurn p 49

- ^ a b Valerian Cardinal Gracias (6 March 1976). "Archbishop T. D. Roberts, S.J.". The Examiner.

- ^ Hurn p 52

- ^ a b c "Archbishop Roberts: A [Pax Christi] Friend's Tribute". Catholic Herald. 5 March 1976.

- ^ "Black Popes: Authority its use and abuse". Kirkus Reviews.

...prompted, we feel sure, by attacks on Catholic authoritarianism such as American Freedom and Catholic Power.

- ^ Black Popes pp 4-33

- ^ Hurn p 68 et seq

- ^ Hurn p 69

- ^ Hurn p 74

- ^ Hurn pp 77-82

- ^ a b Black Popes p 5

- ^ Hurn p 70

- ^ Hurn pp 65-66

- ^ Hurn p 10

- ^ Hurn p 43

- ^ Hurn p 67

- ^ Hurn pp53, 162

- ^ Objections pp 185-186

- ^ Hurn p 64

- ^ Objections, pp 182 et seq

- ^ Quoted in Objections, pp 183

- ^ Extracts quoted in Hurn pp 61-67

- ^ Short, John (31 March 1968). "Protests". Catholic Pictorial.

- ^ O'Hare, J.A. (2003). "Roberts, Thomas d'Esterre". New Catholic Encyclopedia. The Gale Group Inc.

- ^ "delation". Oxford Living Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ Hurn p 100

- ^ Diary... chapter 2, pp 23-35

- ^ Congar, Yves (2012). My Journal of the Council. Liturgical Press. p. 45. ISBN 9780814680292. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ Black Popes p 6

- ^ Hurn chapter nine, pp 94-112;

- ^ Aguiar p 73

- ^ Hurn p 130

- ^ a b Slevin, Gerald (23 March 2011). "New birth control commission papers reveal Vatican's hand". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ Resolution 115, The Lambeth Conference, Resolutions Archive from 1958, https://www.anglicancommunion.org/media/127740/1958.pdf

- ^ Search article is quoted in Hurn pp 131-136 and also in "Pope and Pill". Wijngaards Institute for Catholic Research. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Hurn pp 137-143

- ^ Objections p 177

- ^ Objections pp 173, 176-180

- ^ Hurn p 125

- ^ Leo, John (30 July 1968). "Takes Note of Opposition; Dissent is Voiced" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ Moore, Tim (19 August 1968). "Archbishop speaks on the pill". Nationalist & Leinster Times.

- ^ Hurn p 55

- ^ Quoted in Hurn p 128-129

- ^ Hurn p 152

- ^ Hurn p 126

- ^ Thomas Beaudoin, Catholics, Jews, and Vatican II: A New Beginning, quoting from Frederick Franck, Exploding Church (New York: Delacorte Press, 1968), 230, The Historical Text Archive, http://historicaltextarchive.com/sections.php/sections.php?action=read&artid=76

- ^ a b Lucas, Barbara, Women's Liberator, The Month, March 1973, pp 108-109

- ^ University of Cambridge, History, The University after 1945. https://www.cam.ac.uk/about-the-university/history/the-university-after-1945

- ^ Allen, John L, Jnr, Remembering the women of Vatican II, National Catholic Reporter, 12 October 2012)

- ^ Hurn p 160

- ^ Contraception p 23

- ^ Extracts from her letter, which included a discussion of the arguments against female priests, were published in The Church in the World: News and Notes from all Parts, The Tablet, 4 September 1971.

- ^ Letters to the Editor, The Tablet, 18 September 1971.

- ^ Hurn pp 3-5

- ^ "Archbishop Thomas d'Esterre Roberts". Sunday Times Magazine. 5 December 1965.

- ^ Hurn pp 2-6, 155

- ^ Hurn pp 2-3

- ^ Hurn p 154

- ^ Hurn p44

- ^ Hurn p 155

- ^ Corbishley, Thomas, and Hebblethwaite, Peter, One Long Blast on the Whistle, The Month, March 1973, p 67

- ^ Hurn p 156

- ^ Pope Paul VI (28 November 1963). "Pastorale Munus (English translation)". Papal Encyclicals Online.

- ^ Hurn p 158

- ^ Hurn p 50

- ^ "Archbishop silenced by RC authority". Guardian. 12 January 1965.

- ^ "Archbishop withdrew for Jesuits". Guardian. 13 January 1965.

- ^ "Archbishop withdraws from Foyles literary luncheon". Irish Times. 14 January 1965.

- ^ "Students secretary defends Archbishop Roberts". Glasgow Observer. 25 October 1968.

- ^ Zahn, Gordon, The Limits of Legitimate Authority, The Month, March 1973, p 88

Sources

edit- Main sources

Aguiar, B. M., Archbishop in Bombay, The Month, March 1973, pp 68–81.

Archives of the Jesuits in Britain, http://www.jesuit.org.uk/archives-jesuits-britain. A summary of the papers held on Roberts can be seen here: https://archive.catholic-heritage.net/TreeBrowse.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&field=RefNo&key=ABSI%2fSJ%2f13.

Hurn, David Abner (1966). Archbishop Roberts, S.J.: His Life and Writings. Darton, Longman and Todd..

- Additional sources

Balaguer, M.M.; Fernander, Angelo; Gracias, Valerian; Archbishop Thomas D. Roberts, S.J.: Impressions, The Examiner, 15 September 1962.

Dane, Clement, In the Public Eye: Archbishop Roberts, The Universe, 15 December 1950.

Lucas, Barbara (1965). Archbishop Thomas D'Esterre Roberts, S.J. University of Notre Dame Press. (Issue 16 of the series "Men who make the council")

Who Was Who, Vol 7 1971-1980, Black, 1981, ISBN 0713621761.