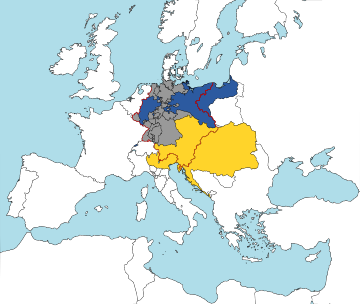

The German question was a debate in the 19th century over the best way to achieve the Unification of Germany. From 1815–1871, hundreds of independent German-speaking states existed. The Großdeutsche Lösung ("Greater German solution") favored unifying all German-speaking peoples under one state, and was favored by the Austrian Empire and its supporters. The Kleindeutsche Lösung ("Lesser German solution") sought only to unify the northern German states and did not include Austria; this proposal was favored by the Kingdom of Prussia. The solutions are also referred to by the states they would create, Kleindeutschland and Großdeutschland ("Lesser Germany" and "Greater Germany"). Both movements were part of a growing German nationalism. The movements also drew upon similar efforts to create a unified nation-state of people who shared a common language in the era, such as the Unification of Italy by the House of Savoy or the Serbian revolution for independence.

While a number of factors swayed allegiances in the debate, the most prominent was religion. The Großdeutsche Lösung would have implied a dominant position for Catholic Austria, the largest and most powerful German state of the early 1800s. As a result, Catholics and Austria-friendly states usually favored Großdeutschland. A unification of Germany led by Prussia would mean the domination of the new state by the Protestant House of Hohenzollern, a more palatable option to Protestant northern German states. Another complicating factor was the Austrian Empire's inclusion of a large number of non-German minorities, such as Magyars, Croats, Czechs, and others. The Austrians were reluctant to enter a unified Germany if it meant giving up their non-German speaking territories.

The debate was settled in favor of the Kleindeutsche Lösung in 1871 with the foundation of the German Empire. Protestant Prussia became the dominant power of the new state, and Austria-Hungary remained a separate polity. While "Greater Germany" would briefly exist from 1938–1945 after Adolf Hitler's Nazi Germany annexed Austria in the Anschluss, the separation of Germany and Austria has otherwise remained.

Background

editOn August 6, 1806, Emperor Francis II of Habsburg had abdicated the throne of the Holy Roman Empire in the course of the Napoleonic Wars with France, thereby ending the loose Empire which had officially unified Germany for a millennium. Despite its later name affix "of the German Nation", the Holy Roman Empire had never been a nation state. Instead its rulers over the centuries had to cope with a continuous loss of authority to its constiuent Imperial States. The disastrous Thirty Years' War proved especially fatal to the Holy Roman Emperor's authority, as the mightiest entities, the Austrian Habsburg Monarchy and Brandenburg-Prussia evolved into rivaling European absolute powers with territory reaching far beyond Imperial borders. The countless small city-states splintered, meanwhile. In the 18th century the Holy Roman Empire consisted of over 1800 separate territories governed by distinct authorities.

This German dualism phenomenon at first culminated in the Seven Years' War, it outlasted the French Revolution and Napoleon's storm over Europe. Facing the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, the ruling House of Habsburg proclaimed the Austrian Empire instead and maintained their title as Emperor. The 1815 restoration by the Final Act of the Vienna Congress established the German Confederation, which was not a nation but a loose association of sovereign states in the territory of the former Holy Roman Empire.

March revolution

editIn 1848, German liberals and nationalists united in revolution, forming the Frankfurt Parliament. The Greater German movement within this National Assembly demanded the unification of all German-populated lands into one nation. In general, the left favored a republican Großdeutsche Lösung, whereas the liberal centre favoured the Kleindeutsche Lösung with a constitutional monarchy. Eduard von Simson, president of the Frankfurt Parliament, is believed to be the one who coined these names.[citation needed]

Austria posed a problem because the Habsburg lands were linked with the Kingdom of Hungary including large Slovak, Romanian and Croat populations. It further comprised numerous possessions with predominantly non-German populations, including Czechs in the Bohemian lands, Poles, Rusyns and Ukrainians in the Galician province, Italians in Lombardy-Venetia as well as Slovenes in Styria, Carinthia, Gorizia and Gradisca and Carniola, making up the larger part of the Austrian Empire. Except for Bohemia and Carniola, these territories were not part of the German Confederation because they had not been part of the former Holy Roman Empire, and all of them had no desire to be included into a German nation state. The Czech politician František Palacký explicitly rejected his mandate to the Frankfurt assembly, stating that the Slavic lands of the Habsburg Empire were not a subject of German debates. On the other hand, for Austrian prime minister Prince Felix of Schwarzenberg, only an accession of the Habsburg Empire as a whole was acceptable because it would not part from its non-German possessions and dismantle in order to remain in an all-German Empire.

Thus, some members of the assembly and namely Prussia promoted the Kleindeutsche Lösung which excluded the whole Austrian Empire with its German and its non-German possessions. Yet, the drafted constitution provided for the possibility for Austria to join without its non-German possessions later. On March 30, 1849, the Frankfurt parliament offered the German Imperial crown to King Frederick William IV of Prussia, who rejected it. The revolution failed and several subsequent attempts by Prince Schwarzenberg to build up a German federation headed by Austria came to nothing.

Austro-Prussian War and Franco-Prussian War

editThese efforts were finally terminated by Austria's humiliating defeat in the 1866 Austro-Prussian War. The Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck, now at the helm of German politics, pursued the expulsion of Austria and managed to unite all German states except Austria under Prussian leadership. Von Bismarck wished to prevent the Austrians and Bavarian Catholics in the south and west from being a predominant force in a mainly Protestant Prussian Germany. Bismarck successfully used the Franco-Prussian War to convince the other German states to stand with Prussia against France; Austria did not participate in the war. After Prussia's speedy victory, it used the prestige it gained to maintain the alliance and declared the German Empire in 1871. Austria was excluded and the Lesser German solution prevailed.