| The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife | |

|---|---|

| Japanese: Tako to ama (蛸と海女) | |

| |

| Artist | Hokusai |

| Year | 1814 |

| Type | Woodcut |

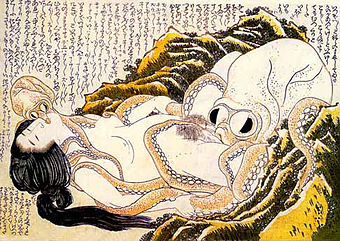

The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife (蛸と海女, Tako to ama, literally Octopus and shell diver) is an erotic woodcut by the Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai. Done in the ukiyo-e style, the print was first published in 1814 in a three-volume collection entitled Kinoe no Komatsu. The work epitomized the shunga, or erotic, style, and influenced many artists and art forms. The print depicts a woman engaged in seemingly consensual intercourse with a pair of octopus; one is seen giving he cunnilingus, while the other caresses her breast and kisses her. Some scholars have asserted that the piece takes it subject matter inspiration from a Japanese legend in which a pearl diver steals from a sea god, and is pursued by ocean life, including octopuses.

This eroticism would have been more accepted in the east than the west, and has inspired a number of pieces and movements. Hokusai’s work pioneered the realistic depictions of the human form in Japanese erotica. The print began the genre later known as tentacle porn, which became a large part of Japanese hentai pornographic movement after depictions of male genitalia were banned in the country. Works derived from the print have sparked debate over pornography, art, and obscenity in Australia, and even Pablo Picasso drew inspiration from the work on a number of occasions. The film Tampopo also drew its inspiration in large part from the print. It has proven to be one of Hokusai’s most influential pieces.

Background

editKatsushika Hokusai, a draftsman and printmaker, not only epitomized ukiyo-e, a term that translates to the pictures of the floating world in English which are woodblock prints of the Edo period usually depicting theater scenes,[1] but he represented the essence of artistic endeavor and achievement over a period of 70 years of single-minded creativity.[2] Hokusai was born in the Honjo Warigesui distric of Edo, and was adopted by Nakajima Ise, a mirror maker in the service to the shogun.[2] He apprenticed to a wood block engraver from age fifteen to eighteen; at age nineteen he became a pupil to leading ukiyo-e master, Katsukawa Shunshō.[2] After his training under Shunshō, he used the name Sōri; he produced highly individual bijinga, or pictures of beautiful women, works in which the smooth lines and elegant, voluptuous charm of the forms distinguished them from other artists of the time such as Kitagawa Utamaro.[2] From 1798, he changed his name to Hokusai and immersed himself in ukiyo-e.[2] His vigorous, sensitive and humorous style combined with various painting techniques of Japan, China, and the western world revitalized the ukiyo-e tradition, adding landscape to its subject repertory.[3]

Hokusai was one of the main shunga artists of the Edo period; he made at least 30,000 drawings and illustrations for 500 books.[2] One of his most famous shunga prints is The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, which was created around 1814 CE.[4] It was published in three volumes during the Edo period.[5] The work is untitled in the collection, but it is generally know as Tako to ama (蛸と海女, "Octopus and Fisherwoman") in Japanese. However the translation of the title to English differs, varying from Diver and Octopi, Pearl Diver and Two Octopi, The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, and Diver and Two Octopi.[6][7][8]

Shunga, or ‘spring picures’ is a type of Japanese art dedicated to the erotic, and was a theme Hokusai commonly employed in his work.[9] Shunga are colored wood engravings depicting sexual pleasure.[4] The purpose of shunga is sexual education, with an emphasis on family continuity; the audience is often seeking advice for their sex life either practically or emotionally.[9] Unlike western sex books, Japanese shunga was a union of science and art, and there was also a serious belief given to conjugal compatibility in accordance with natural or divination-like forces.[9] Shunga also bore close relationships to literature, since certain literary situations became ‘in vogue,’ and were often part of a unified series.[9] Shunga developed from pillow-books, scrolls of erotic prints designed as manuals of sexual knowledge to be kept inside the pillow, and became popular in Japan by the eight century.[4]

Description and Concept

editThe initial image of The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife is simply a woman being ravished by two octopuses, but the other purpose of the image is revealed in how it interacts with the other images in the shunga book. The text in the print is a dialogue between the creature and the woman, in which they express mutual sexual enjoyment.[9] Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife is considered one of the most beautiful Japanese erotic prints; it is truly frightening, says Lane.[8] The image consists of a Japanese woman mounted by two octopi; one with its tentacles wrapped around her nipples while his head performs cunnilingus.[8] The smaller octopus, possible the offspring of the larger octopus, is delving into the woman’s mouth while it also caresses her nipples.[8] The woman herself almost has a superhuman expression of agony and sorrow, according to Lane, which convulses this long, graceful female figure with an aquiline nose - and the hysterical joy - which emanates at the same time from her forehead, from those eyes closed as in death are admirable.[8] The effect of the painting is neither comic or pornographic; in this fantasy of a passionate shell-diver, according to Lane, we discover a new facet of Hokusai’s genius, and consummate work of erotic art.[8] Edmond de Goncourt, a European man of the time, wrote, “A terrible plate: on rocks green with marine plants is the naked body of a woman, swooning with gratification, siat cadaver, to such a degree that one cannot tell whether she is drowned or alive, and an immense octopus, with frightening eye-pupils in the shape of black moon segments, sucks the lower part of the body, while a small octopus battens on her mouth.”[10]

Some scholars, such as Danielle Talerico, believe that the image is derived from the story of Princess Tamatori, which was highly popular in the Edo period.[7] In the story, Tamatori is a shell diver who marries Fujiwara no Fuhito of the Fujiwara clan, who is searching for a pearl stolen from his family by the dragon god of the sea named Ryūjin. Tamatori dives down to Ryūjin’s under sea palace of Ryūgū-jō. Ryūjin then pursues Tamatori with his army of sea creatures, including octopuses. To escape with the jewel, she cut open her breast and places the pearl inside, which allowed her to swim faster, but she dies from her wound shortly after surfacing.[7] In the text above Hokusai’s print, it states that the big octopus will bring the woman to Ryūjin’s palace, which creates the tie to the story of Princess Tamatori.[7]

Style

editWoodblock print production in seventeenth century Japan were made by transferring the artists original drawing to wood, then inking the wood and printing it on paper.[11] The artist used a different block for each color by registering the print, alining the new colored area with the previously printed color, and usually the prints were created by a team of artisans overseen by a publisher.[11] During the Edo period Japan evolved and refined its highly sophisticated and successful method of reproducing images in quantities from woodblocks. The method used during the Edo period was a combination of Chinese Woodblock printing and Western Chiaroscuro Woodcut printing, European woodblock printing in which two or more woodblocks were printed on top of the other, usually consisting of flat tonal blocks with limited chromatic range and a line block printed last.[12] The elements needed for woodblock printing were readily availble in Japan such as the correct paper fiber, the right pigments, the bamboo baren, a pad used to take the impression from the woodblock by rubbing the paper vigorously with a circular motion, and the wood for the blocks.[13] Minerals from the earth, flowers, bark, grasses were used for pigments, as were dayflower, safflower, gamboge, orpiment, red lead, indigo, vermilion, and azurite. The pigments used to create the ink in the eighteenth century were mostly organic, therefore they are very sensitive to light and water. Many prints that still existing today have faded in color because of the exposure to the elements.

The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife provides an example of the shunga art style, which consists of a colored woodblock print.[9] Japanese woodblock color prints are called ukiyo-e, which are more traditional than contemporary Europe-oriented Japanese wood engraving.[14] The Japanese treat nudity in their art is very different then western art. The naked form appeared only incidentally: in scenes of disaster and pillage, or bathing. Nudity rarely involved an erotic connotation, and in shunga the context is erotic, the nudity is not.[8] In Japan there were periods of government reform where bans on nudity caused seminudity to flourish briefly in ukiyo-e.[8] The universality of communal bathing in Japan has removed the erotic implications from nudity, and beautiful garments that partially conceal or emphasize sexual organs are considered truly voluptuous. Since the exposure of genitals is not uncommon among the Japanese, artist tend to exaggerate them for dramatic affect.[4]

There was also little of tradition of drawing the figure from life, and no drawing of the nude figure.[8] The lack of anatomical study put the Japanese artist at disadvantage when depicting the human form, thus most artist of the Edo period did not depict the human form; Hokusai was a pioneer in this category.[15] Hokusai arranged his naked or semi-naked couples in gymnastic convolutions to avoid showing genitalia.[16] The use of expresive pictorial structures and flat decorative color in the composition of ukiyo-e prints are formulaic. However, the formulaic elements artistically deployed in a manner that serves not only to convey but to solicit sexual arousal from the viewer as one attends to these features.[17]

“Hokusai’s passionate ‘search for form’ shows a kinship with western art that goes surprisingly deep, but it may not be from western influence at all,” suggests scholar Michael Sullivan, “In the preparatory drawings for some of the prints such as The Rape, he goes over the line again and again in his search for the most telling contour, giving this sheet the extraordinary Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife almost the quality of a seventeenth century Italian drawing.”[18]

Influences

editHokusai’s style is very similar to his teacher Shunshō, and with out his signature, Hokusai’s pieces would be very difficult to distinguish from the work of his fellow pupils in the Shunshō school.[19] From about the year 1806, Hokusai became engrossed in the detailed illustration of ‘Gothic Novels.’ The influence of these novels along with the classical Chinese painting lead gradually to a change of style resulting in more powerful and monumental figures, but a loss of the willowy grace of his earlier work in the ukiyo-e manner.[20] “However, there were a couple of years from 1806 to 1808 where the two contrasting styles merge or rather struggle for domination”, according to Lane, “thus in the intriguing cover to a theater-booklet of 1808, we can see both somthing of the pliant grace of the earlier Hokusai, and the beginnings of that harder, less graceful style of his middle period.”[20]

Reception and Impact

editAs result of The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, the tentacle porn movement began, according to Sparling.[21] The tentacle porn movement was influenced by many factors and gained its momentum through the Shinto religion and shunga such as The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife.[21] Tentacle porn resurfaced and became very popular in Japan after World War II. The occupying forces in Japan at the time implemented laws banning the representation of genitalia in sexual acts; this created a block for erotic art at the time because the difficulty of showing sexual acts without depicting the genitals.[21] To get around these laws artist of the time turned to tentacles because of their long phallic shape, thus tentacle pornography took off in Japan.[21] Even today when people have easy access to conventional hentai, erotic graphic novels, and porn, people still enjoy tentacle porn.[21]

The print has an unconventional subject matter for the West along with other places around the world, which causes some controversy.[22] The piece stirred the waters not only in the nineteenth century, but also in modern times. In 2003, an art versus pornography debated started in Melbourne, Australia over a piece also called The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife by David Laity, which was inspired by Hokusai’s print.[22] A government funded gallery is negotiating the purchase of the print; Metro 5 Gallery director Brian Kino received more than fifty threatening phone calls about the piece. Some people even threatened to bomb the gallery where the piece is being shown, and because of its content the Australian Family Association national vice-president, Bill Muehlenberg, said it should be taken down and not shown in a public gallery.[22] The artist, however, disagrees saying, “I don’t think it’s controversial or is going to have any effect on anyone. I can’t see hundreds of women jumping off St. Kilda pier in search of octopus as a result.”[22]

Pablo Picasso is another western artist who was inspired by Hokusai’s print The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife; which have been the subject of an exhibition at the Barcelona Museu Picasso in 2009. “Secret Images” aims to show the influence of the nineteen erotic prints of Picasso. The prints, from the seventeenth to nineteenth century and which were a part of Picasso’s private collection, are displayed alongside the twenty-seven engravings and drawings of Picasso that they inspired. Picasso was very influenced by the detailed work of Japanese artists, such as Hokusai, depicting genital organs during sex.[23]

Another work of art that Hokusai’s print influenced is Tampopo. The director Juzo Itami creates links between food and eating, along with various human situations and relationships, including sex, according to Scholar Zvika Serper.[24] Tampopo was filmed in 1985, and Itami uses a western story of a stranger riding into town, finding a shabby restaurant; who then turns into the best in town then drifts away again. Itami uses this story as the canvas of his sensual exploration, because as he states, “It was spineless. It needed a strong plot, a clear narrative.”[24] Itami reveals the sensual aspect of food and eating, such as touching, licking and biting.[24] In Tampopo the dancing lobster in the scene where Itami replaces static food with active food to become a symbol of sex, states Serper, it is positioned between the woman’s vulva and breasts which is very similar to The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife. Noboru Sawai is a Japanese artist that was inspired by The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, and created the piece entitled Fisherman’s Dream in 1991. It is a woodblock prink with intaglio depicting a bountiful harvest of fish in the lower register of the piece. In the top register are scenes with both women, men and sea creatures preforming sexual acts.[9] This piece was influenced by the legend of Princess Tamatori, similar to The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife.[9]

Notes

edit- ^ Clark and Clark "Ukiyo-e" (2010).

- ^ a b c d e f Naitō (2010), 1.

- ^ Naitō (2010), 2.

- ^ a b c d Webb (2010).

- ^ Ulenbeck (2005), 56.

- ^ Forrer (1992), 124.

- ^ a b c d Talerico (2001), 24-42.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lane (1989), 166.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lenehan-White (2006).

- ^ Avurtich (1991), 84.

- ^ a b Clark and Clark "Japanese Prints" (2010).

- ^ Johnson (2010).

- ^ Kurml (2010).

- ^ Tschichold (1971), 75-79.

- ^ Lane (1989), 167.

- ^ Calza (2003), 192.

- ^ Kieran (2002), 6.

- ^ Sullivan (1989), 34.

- ^ Lane (1989), 163.

- ^ a b Lane (1989), 152.

- ^ a b c d e Sparling (2007).

- ^ a b c d New Zealand Press Association (2010).

- ^ Mallen (2009).

- ^ a b c Serper (2003), 72-89.

References

edit- Avurtich, Sharon (1991). The Japanese Picture Book: A Selection from the Ravicz Collection. New York City: Harry N. Abrams.

- Clark, Michael (2010). "Japanese Prints". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms. Oxford Art Online. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- Clark, Michael (2010). "Ukiyo-e". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms. Oxford Art Online. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Forrer, Matthi (1992). Hokusai: Prints and Drawings. New York City: Prestel. ISBN 3791342223.

- Johnson, Jane (2010). "Woodcut, chiaroscuro". Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- Kieran, Matthew (2002). "On Obscenity: The Thrill and Repulsion of the Morally Prohibited". Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 64 (1). Providence, Rhode Island: International Phenomenological Society: 31–55. doi:10.1111/j.1933-1592.2002.tb00141.x. JSTOR 3071018. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- Kruml, Richard (2010). "Japanese §IX: Prints and Books: Edo Period". Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- Lane, Richard (1989). Hokusai Life and Work. London: Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 0525244557.

- Lenehan-White, Anne (2006). "Shunga and Ukiyo-e: Spring Pictures and Pictures of the Floating World". Northfield, Minnesota: St. Olaf College. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- Mallen, Enrique (6 November 2009). "Picasso's Japanese erotic inspiration on show in Barcelona". On-Line Picasso Project. Huntsville, Texas: Sam Houston State University. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- Naitō, Masato (2010). "Katsushika Hokusai". Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- New Zealand Press Association (21 October 2003). "Love is a many-tentacled thing..." The New Zealand Herald. Auckland, Australia. APN News & Media. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- Serper, Zvika (2003). "Eroticism in Itami's 'The Funeral' and 'Tampopo': Juxtaposition and Symbolism". Cinema Journal. 42 (3). Norman, Oklahoma: Society for Cinema and Media Studies: 70–95. doi:10.1353/cj.2003.0012. JSTOR 1225905. S2CID 194071119. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- Sparling, Shayna (27 October 2006). "When Tentacles Tantalize". Imprint. Imprint Publications. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- Talerico, Danielle (2001). "Interpreting Sexual Imagery in Japanese Prints: A Fresh Approach to Hokusai's Diver and Two Octopi". Impressions. 23. Ukiyo-e Society of America.

- Tschichold, Jan (Winter 1971). "Chinese and Japanese Colour Wood-Block Printing". Leonardo. 4 (1). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Uhlenbeck, Chris (2005). Japanese Erotic Fantasies: Sexual Imagery of the Edo Periods. Hotei. ISBN 9074822665.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Webb, Peter (2010). "Erotic Art". Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

Further reading

edit- Behrens, Roy (April 2006). "Hokusai". Leonardo. 3 (2). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Berry, Paul (2004). "Rethinking "Shunga": The Interpretation of Sexual Imagery of the Edo Period". Archives of Asian Art. 54. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press: 7–22. doi:10.1484/aaa.2004.0002. JSTOR 20111313. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- Lillehoj, Elizabeth (Summer 2005). "Gender and Power in the Japanese Visual Field". Journal of Japanese Studies. 31 (2). Society for Japanese Studies: 453–458. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Mitchell, C. H. (Autumn 1976). "Shunga: The Art of Love in Japan". Monumenta Nipponica. 31 (3). Tokyo: Sophia University: 323–324. doi:10.2307/2384219. JSTOR 2384219. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Zatlin, Linda Gertner (1997). "Aubrey Beardsley's "Japanese" Grotesques". Victorian Literature and Culture. 25 (1). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 87–108. doi:10.1017/S1060150300004642. JSTOR 25058375. S2CID 162596064. Retrieved 23 November 2010.