The Persian embassy to Siam (1685–1687) was sanctioned by Shah Sulaiman I in response to an envoy sent to Persia in 1682 by King Narai of Siam. The embassy departed Persia in June 1685 and sailed via Madras to the Siamese port of Mergui. The delegates then crossed the peninsula's jungles to reach the royal capital, Ayuthaya, before heading north to meet King Narai at his palace in Lopburi. After an exchange of formalities, including the presentation of Shah Sulaiman's letter to King Narai, the Persians were invited to remain in the country and accompany the king on elephant and tiger hunts. The embassy left Siam early in 1687 and following protracted delays and an encounter with pirates in India, arrived back in Persia in May 1688.

Sources

editSources include the Ship of Sulaiman, a travelogue written by the mission's secretary in a "contrived, metaphorial" style characteristic of Safavid literature. The account was translated into English from a British Museum manuscript and described by David Wyatt as "among the most important primary sources for the history of Siam in the reign of King Narai".[3][a] British British East India Company records document aspects of the embassy's voyage from Persia to Siam and provide detail about the delegates, their entourage and cargo.[5] French envoys present in Siam in 1685 were aware of the Persians and expressed concerns that the embassy's motive might be to convert King Narai to Islam.[6] Siamese sources include the Royal Chronicles of Ayuthaya, though the earliest of these to cover the period under review was not written until 1795.[7] Aside from being secondary rather than primary sources, a major problem with these chronicles is that the identity of non-Siamese individuals is frequently obscured by the use of formal titles and generic names that shed little light on the name or nationality of those concerned.[8] Modern sources include David Wyatt's A Persian Mission to Siam in the Reign of King Narai, and Safine-ye Solaymani, an overview of the Ship of Sulaiman published on Encyclopædia Iranica.[9]

Background

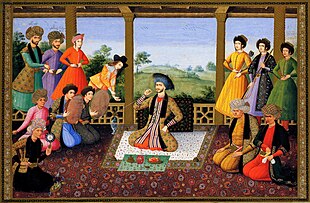

editIn the early years of the seventeenth century a Persian community took root in the Siamese capital, Ayuthaya. Prominent members of this enclave included brothers Sheikh Ahmad and Muhammad Said, who arrived in the city during the reign of King Naresuan. Sheikh Ahmad worked closely with Kings Songtham and Prasat Thong, and was eventually appointed Phra Khlang, the Siamese official responsible for foreign affairs.[10] The Persian community grew and by the middle of the seventeenth century wielded considerable political influence in the kingdom. Sanjay Subrahmanyam described this florescence as an "Iranian revolution". Locally resident Persians were instrumental in bringing about King Narai's accession to the throne; a large contingent of Persian soldiers was recruited from India to serve as the royal bodyguard; Simon de la Loubère, French envoy to Siam in 1687, noted that "the Principal Offices of the Court, and of the Provinces were then in the hands of the Moors".[11] King Narai was strongly influenced by the Persians in his kingdom: he not only ate their cuisine but adopted a similar style of dress and dining etiquette.[12] At least two academics have referred to him as an Iranophile.[13]

King Narai sent an envoy to Persia in 1682, but despite his admiration for Persians and their culture, it is not clear why.[14] Engelbert Kaempfer reported seeing the envoy at Isfahan in 1684 and claimed his mission was to enlist naval support in a Siamese military campaign against the Burmese Kingdom of Pegu.[15] King Narai may also have wanted to forge diplomatic ties to consolidate existing bilateral trade; another possibility is he was seeking an alliance with Persia to counter the growth of Mughal commerce and the empire's incursions into the Deccan sultanates.[16] Unclear too are the reasons why Shah Sulaiman dispatched a reciprocal embassy in 1685. The embassy's secretary stated emphatically that the mission's purpose was to convey goodwill, but such an innocuous motive little justifies the time and expense needed to mount the expedition.[17] French concerns that the Persians were attempting to convert King Narai to Islam have been dismissed (the delegates were military men rather than Muslim clerics); one academic suggested the mission may have been countenanced by Shah Sulaiman's grand vizier, Sheikh Ali khan Zangeneh, who took a keen interest in commerce and was eager to increase revenue from international trade.[18]

French priests from the Missions Étrangères arrived in Siam in 1662. Inspired King Narais's generosity, religious tolerance and interest in Christianity, the priests saw an opportunity to convert him to Catholicism and duly recommended forging diplomatic ties between his country and theirs. Letters from Europe followed: King Louis XIV and Pope Clement IX wrote to King Narai, thanking him for the kindness and care he had shown French ecclesiastics and counselling him to maintain the religious freedom he had granted them. The Siamese monarch received the letters in 1673 and

Embassy

editThe greatest part of the Kingdom of Siam lies between the Golf of Siam and the Golf of Bengala; bordering upon Pegu toward the North, and the Peninsula of Malacca toward the South. The shortest and nearest way for the Europeans to go to this Kingdom, is to go to Ispahan, from Ispahan to Ormus, from Ormus to Surat, from Surat to Golconda, from Golconda to Maslipatan, there to embark for Denouserin (Tenasserim), which is one of the Ports belonging to the Kingdom of Siam. From Denouserin to the Capital City, which is also call'd Siam, is thirty-five days journey, part by Water, part by Land, by Waggon, or upon Elephants. The way, whether by Land or Water, is very troublesome; for by Land you must be always upon your guard, for fear of Tigers and Lions; by Water, by reason of the many falls of the River, they are forc'd to hoise up their Boats with Engines.

– Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, The Six Voyages of John Baptista Tavernier, 1678.[19]

In June 1685 the envoys departed the Persian Gulf port of Bandar Abbas on an English vessel bound for Madras; they took with them a cargo of "magnificent presents" and a letter from Shah Sulaiman to King Narai.[20][b] Ambassador Muhammad Hussein Beg led the delegation; secretary Ibn Muhammad Ibrahim kept a written record of the mission.[23] British East India Company records describe the delegates' reception at Madras and how they were escorted ashore by Elihu Yale, the future governor of Fort St George and philanthropist after whom Yale University is named.[24] About three weeks later on September 7 the Persian delegates left Madras and continued their journey eastward across the Bay of Bengal to Siam.[25][c] After passing the Andaman Islands and narrowly escaping shipwreck near Pegu, the embassy entered Siamese waters, weighed anchor at the port of Mergui and continued by boat to Tenasserim.[29] François-Timoléon de Choisy, France's envoy to Siam in 1685, described the Persian ambassador's "impertinent" behavior at Tenasserim, claiming he borrowed money from the local governor, refused to pay the English sea captain whose ship had brought the embassy to Siam, and complained bitterly about Siamese food.[30] True or not, the ambassador never had a chance to respond: his health had deteriorated since leaving Bandar Abbas and by the time the embassy reached Siam he was critically ill. Doctors were called, but to no avail; on December 19 the Persian ambassador died.[31]

Despite their loss the remaining delegates decided to continue across the peninsula to Ayuthaya. The journey lasted six weeks and included travel by boat and elephant that took the delegates first to Phetchaburi, then Suphanburi, and finally their destination.[32] On arrival in Ayuthaya the Persians were told the king had left the city and gone to the second capital, Lopburi.[1] The delegates promptly continued north to Lopburi and after a three-week delay were granted an audience with King Narai.[33] The king graciously accepted the letter from Shah Sulaiman and asked about the shah's health and if Persia were at war; he then invited the Persians to remain in Siam as his guests and join him that evening on an elephant hunt.[34] The delegates accompanied the king on two elephant hunts during their stay in Lopburi; they also spectated at a tiger hunt, participated in a falconry expedition, toured the city's temples and attended numerous banquets.[35] When the monsoon started the king and the Persians returned to Ayuthaya.[36] After further meetings with Narai, the presentation of farewell gifts and a letter for Shah Sulaiman, the delegates departed Ayuthaya in January 1687 aboard an Indian merchant ship that took them past the Sultanate of Pattani, into the Malacca Straits and across the Bay of Bengal to India.[37] Following a protracted stopover at Cochin and an encounter with pirates en route to Surat, they spent three and a half months at Bombay before heading back to the Persian Gulf. They arrived home in Bandar Abbas on 14 May 1688.[38]

Assessment

editAftermath

editAccording to Encyclopædia Iranica the embassy was probably the last diplomatic contact between Persia and Siam until formal ties between the two countries were established in the 20th century.[39]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ The manuscript was initially thought to be unique, but a second copy is known to exist at the Malik National Museum in Tehran. A Persian language edition of the text was published in Tehran, 1977.[4]

- ^ The phrase "magnificent presents" is a translation of De Choisy's description, "présens magnifiques". De Choisy and the British East India Company also refer to the embassy's large number of attendants.[21] King Narai's "extremely precious gifts" to Shah Sulaiman (presented at the court of Isfahan in 1684) consisted of golden vessels, Chinese porcelain, Japanese lacquerware and a collection of rare birds. Engelbert Kaempfer described the presentation ceremony, observing that a retinue of forty bearers was needed to convey the gifts.[22]

- ^ Dates given by the Persian embassy's secretary do not reconcile with British East India Company records. For example, the secretary claimed the embassy departed Bandar Abbas on June 27 1685; he said fourteen days were needed to reach Muscat and a further forty seven days were spent traveling to Madras. This implies the embassy arrived in Madras towards the end of August.[26] British East India Company documents record the embassy's arrival on July 29.[27] Departure dates from Madras are also an issue: the embassy's secretary gave September 16; British accounts give September 7.[28]

Citations

edit- ^ a b Marcinkowski (2002a).

- ^ De Choisy (1687), p. 195; Tachard (1686), p. 308.

- ^ Wyatt (1974), pp. 151, 153, 157.

- ^ Marcinkowski (2002c), pp. 40–41.

- ^ Records of the Relations between Siam and Foreign Countries in the 17th Century. Volume 3, pp. 341, 380–2, 385–386.

- ^ Rota (2010), pp. 74–75; De Choisy (1687), p. 195; Tachard (1686), p. 308.

- ^ Suwannathat-Pian (1979), pp. 205–206.

- ^ Suwannathat-Pian (1979), p. 203; Marcinkowski (2002b).

- ^ Wyatt (1974), pp. 151–157; Marcinkowski (2002a).

- ^ Scupin (1980), pp. 62–64.

- ^ Marcinkowski (2002c), pp. 36–38; Loubère (1693), p. 112.

- ^ Scupin (1980), pp. 66–67.

- ^ Marcinkowski (2005), p. 34; Rota (2010), p. 72.

- ^ Wyatt (1974), p. 151; Rota (2010), p. 71.

- ^ Marcinkowski (2002c), p. 35; Rota (2010), p. 72.

- ^ Rota (2010), pp. 71–73.

- ^ Ibn Muhammad Ibrahim (1972), p. 61; Rota (2010), pp. 73–75.

- ^ Rota (2010), pp. 73–75; Matthee (2015a).

- ^ Tavernier (1678), p. 189.

- ^ Marcinkowski (2002a); De Choisy (1687), p. 195; Records of the Relations between Siam and Foreign Countries in the 17th Century. Volume 3, p. 380.

- ^ De Choisy (1687), p. 195; Records of the Relations between Siam and Foreign Countries in the 17th Century. Volume 3, p. 380.

- ^ Marcinkowski (2002c), p. 35.

- ^ Ibn Muhammad Ibrahim (1972), pp. 17, 20–21.

- ^ Records of the Relations between Siam and Foreign Countries in the 17th Century. Volume 3, p. 382; Elihu Yale (Encyclopædia Britannica).

- ^ Records of the Relations between Siam and Foreign Countries in the 17th Century. Volume 3, pp. 385–386.

- ^ Ibn Muhammad Ibrahim (1972), pp. 25, 29–30, 33.

- ^ Records of the Relations between Siam and Foreign Countries in the 17th Century. Volume 3, p. 380.

- ^ Ibn Muhammad Ibrahim (1972), p. 43; Records of the Relations between Siam and Foreign Countries in the 17th Century. Volume 3, pp. 385–386.

- ^ Ibn Muhammad Ibrahim (1972), pp. 43–44, 47; Marcinkowski (2002a).

- ^ De Choisy (1687), pp. 242–243.

- ^ Alam and Subrahmanyam (2007), p. 164; Marcinkowski (2005), p. 24.

- ^ Alam and Subrahmanyam (2007), p. 164; Marcinkowski (2005), pp. 24–25; Wyatt (1974), p. 152.

- ^ Alam and Subrahmanyam (2007), pp. 165–167; Ibn Muhammad Ibrahim (1972), pp. 60–62.

- ^ Ibn Muhammad Ibrahim (1972), pp. 61–65; Marcinkowski (2005), p. 26.

- ^ Ibn Muhammad Ibrahim (1972), pp. 69–74.

- ^ Ibn Muhammad Ibrahim (1972), pp. 74–75; Marcinkowski (2005), p. 26.

- ^ Alam and Subrahmanyam (2007), p. 168.

- ^ Marcinkowski (2005), pp. 30–31.

- ^ Marcinkowski (2002b).

Sources

editEncyclopædia Britannica

- "Constantine Phaulkon: Greek Adventurer". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- "Elihu Yale: English Merchant and Philanthropist". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- "Narai: King of Siam". Encyclopædia Britannica.

Encyclopædia Iranica

- Marcinkowski, Muhammad Ismail (2002a). "Safine-ye Solaymani". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Marcinkowski, Muhammad Ismail (2002b). "Thailand-Iran Relations". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Matthee, Rudi (2015a). "Sayk-Ali Khan Zangana". Encyclopædia Iranica.

Books: primary sources

- De Choisy, François-Timoléon (1687), Journal ou Suite du Voyage de Siam (in French), Amsterdam: Chez Pierre Mortier

- Ibn Muhammad Ibrahim (1972). The Ship of Sulaiman. Translated by John O'Kane. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 023103654X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|layurl=ignored (help) - Loubère, Simon de la (1693), A New Historical Relation of the Kingdom of Siam. Volume 1, London: Horne

- Records of the Relations between Siam and Foreign Countries in the 17th Century. Volume 3, 1680–1685, Bangkok: Vajiranana National Library, 1916

- Tachard, Guy (1686), Voyage de Siam des Peres Jesuites (in French), Paris: Chez Arnould Seneuze et Daniel Horthemels

- Tavernier, Jean-Baptiste (1678), The Six Voyages of John Baptista Tavernier, London

Books: secondary sources

- Alam, Muzaffar; Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (2007), Indo-Persian Travels in the Age of Discoveries, 1400–1800, UK: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521129559

- Marcinkowski, Muhammad Ismail (2005), From Isfahan to Ayutthaya: Contacts between Iran and Siam in the 17th Century, Singapore: Pustaka Nasional Pte Ltd, ISBN 9971774917

- Rota, Giorgio (2010), "Diplomatic Relations between the Safavids and Siam in the 17th Century", in Kauz, Ralph (ed.), Aspects of the Maritime Silk Road: From the Persian Gulf to the East China Sea, Weisbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 71–84, ISBN 3447061030

Journals

- Marcinkowski, Muhammad Ismail (2002c), "The Iranian-Siamese Connection: An Iranian Community in the Thai Kingdom of Ayutthaya", Iranian Studies, 35 (1/3), International Society for Iranian Studies: 23–46, ISSN 0021-0862

- Love, Ronald S. (2001), "Lost at Sea: The Tragedy of the Soleil d'Orient and the First Siamese Embassy to France, 1680–1684", The Proceedings of the Western Society for French History, 29 (1), Western Society for French History: 60–71, ISSN 2573-5012

- Scupin, Raymond (1980), "Islam in Thailand before the Bangkok Period" (PDF), Journal of the Siam Society, 68 (1), Bangkok: The Siam Society: 55–71, ISSN 0857-7099

- Suwannathat-Pian, Kobkua (1979), "Devolepment of Thai Historiography: Part I" (PDF), Jebat: Malaysian Journal of History, Politics & Strategic Studies, 9 (1), Kuala Lumpur: National University of Malaysia: 195–207, ISSN 2180-0251

- Wyatt, David (1974), "A Persian Mission to Siam in the Reign of King Narai" (PDF), Journal of the Siam Society, 62 (1), Bangkok: The Siam Society: 151–157, ISSN 0857-7099