| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Marxian economics |

|---|

|

Marxism and Keynesianism

editThe work of economists John Maynard Keynes and Karl Marx has been extremely influential within the study of economics. With both men's works fostering respective schools of economic thought (Marxian Economics and Keynesian economics) that have had significant influence in both various academic circles, along with influencing government policy of various states. Keynes' work found popularity in developed liberal economies following the Great Depression and World War II, most notably Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal in the United States. While Marx's work, with varying degrees of faithfulness, led the way to a number of socialist republics, notably the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China, among others. The immense influence of both Marxist and Keynesian schools has therefore led to numerous comparisons of the work of both economists along with synthesis of both schools.

With Keynes' work stemming from the neoclassical tradition, and Marx's from Classical economics and German idealism (notably the work of Georg Wilhem Friedrich Hegel), their understandings of the nature of capitalism varied, however both men also held significant similarities in their work. Unlike the Classical and Neoclassical economists who influenced them, both Marx and Keynes saw significant faults within the capitalist system (albeit to varying degrees), this is in opposition to many Classical and Neoclassical economists who tend to understand that faults within a capitalist system are brought upon by market imperfections and the influence of "exogenous shocks to the macroeconomic system".[1] Central to this comparison however, is the distinction between Keynes' belief in remedying the faults of capitalism, while Marx saw Capitalism as a stepping stone towards further societal development.[2]

Views on Crisis

editUnlike their Classical and Neoclassical contemporaries, both Marx and Keynes understood Laissez-faire capitalism as having inherent crisis associated with it. However despite these similarities both their understanding of capitalist crisis as well as the possible remedies for it, differ heavily. Keynes understood that majority of economic recessions were a result of fluctuating investment within business cycles, with low capital investment resulting in recession and deflation and high investment resulting in boom and inflation.[3] [4]Keynes believed that these business cycles of capitalist economies be remedied by sufficient interference by the state in order to maintain full employment and a strong economy. His influence over the multiplier theorem proved extremely substantial in outlining the effectiveness that state economic intervention can have in compensating during economic downturn.[5] Furthermore, Keynes understood how the raising and lowering interest rates could be used as a means of combating economic imbalance. Keynes used his findings to promote 'counter-cyclical policy', primarily explored within his 1930 work, A Treatise on Money. Keynes believed that by lowering interest rates during a recession, investment in the economy would be stimulated, while interest rates could be raised to counter inflation.[6] In broad terms, Keynes believed that the crisis associated with capitalism could be effectively controlled by utilizing effective government policy though both monetary and fiscal means.

In a similar vain to Keynes, Marx believed crisis to be inherent to the processes of capitalism. Marx understood crisis as deriving within the capitalist system and as the result of a breakdown within the process of capital accumulation as brought upon by imbalances within the accumulation process. These imbalances are primarily caused by general overproduction, as brought upon by the desire for capitalists to maximize their attainment of surplus value, and necessity to increase productive capacity to ensure higher returns, however the lack of effective demand within an economy limits the ability for the entire economy to grow alongside the rise of production.[7] Marx further explores how the failure of overproduction within a single industry can greatly effect the livelihood of workers, notably found with his cotton cloth example:

Furthermore, Marx claims that the interconnected nature of production and markets increases the fragility of both and will therefore have widespread effects on the economy if general overproduction occurs.[10] From here we can understand that while both may be critical of the crisis found in capitalism, their interpretations of its foundations differ, with Marx focusing on failure within production whereas Keynes focuses on investment.

Views on Social Conflict

editFor Marx and Keynes, their respective understandings of social hierarchy and class conflicts have similar foundations yet substantial differences in their relative understandings. Marx saw class conflict as the primary driver towards social change and development (as per dialectical materialism), with the growing economic divide between the capitalist class and proletariat resulting in class conflict and subsequent socialist revolution.[11] Furthermore, Marx understood this class conflict as inherent within the structure of capitalism, as with the establishment of hierarchical classes also brings with it the foundations on which conflict arises.[12]

In contrast however, Keynes viewed social conflict as a fault in capitalism which can be adjusted through the implementation of public intervention into the economy, as "Public intervention is a more elevated response to a natural state of inter-class conflict which feeds into itself".[13] Keynesian economics therefore, acted as a 'middle-way' for many developed liberal capitalist economies to appease the working class in lieu of a socialist revolution.[14] Keynes himself was also argued against the creation of a class war, noting that "The class war will find me on the side of the educated bourgeoisie."[15]

However despite these differences, Keynes and Marx both saw that Laissez-faire Capitalist economies inherently stratify social classes. However, Keynes had a significantly more optimistic view in regards to the effectiveness of the state in promoting social welfare and a decent standard or living, unlike Marx who was substantially more critical of the dangers posed upon the proletariat inherent within Capitalism.[16] For Marx the 'fix' for the class struggle in a capitalist system is the abolition of class itself, and subsequent establishment of socialism.[17]

Views on Unemployment

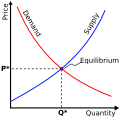

editFor both Marx and Keynes, analyzing and combating the dangers of unemployment were key to understanding the capitalist system. Majority of the Classical and Neoclassical orthodoxy agree that Say's Law allows for an economy to maintain full employment by mechanisms of equilibrium within capitalism that allow for equality of aggregate supply and demand.[18] However, both Marx and Keynes refute the viability of Say's Law occurring within the economy.

For Keynes, unemployment within a capitalist economy was deemed as a significant social ill of economies, as observed by the mass unemployment following the First World War. Keynes saw that the two popular remedies for unemployment were "real wage cuts... and general austerity", were ineffective in contrast to public intervention within the economy.[19]

Heterodoxy and Keynes-Marx synthesis

edit- ^ Aliber, R. Z.; Kindleberger, C. P. (2015). Manis, Panics , and Crashes: A History of Financial Crisis. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 39.

- ^ Matyas, A. (1983). "Similarities Between the Economic Theories of Marx and Keynes". Acta Oeconomica. 31 (3/4): 1.

- ^ "Treatise on Money and the General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money 1927 to 1939". maynardkeynes.org.

- ^ Keynes, John Maynard (1950). A Treatise on Money. London: Macmillan and co. pp. 148–149.

- ^ Chang, Ha-Joon (2014). Economics: The User's Guide. London: Penguin Group. pp. 148–149.

- ^ "Treatise on Money and the General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money 1927 to 1939". maynardkeynes.org.

- ^ Sardoni, Claudio (1987). Marx and Keynes on Economic Recession. New York: New York University Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 0-8147-7871-2.

- ^ Sardoni, Claudio (1987). Marx and Keynes on Economic Recession. New York: New York University Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-8147-7871-2.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1968). Theories of Surplus Value, Part II. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- ^ Sardoni, Claudio. (2011). Unemployment, recession and effective demand : the contributions of Marx, Keynes and Kalecki. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-84844-969-5. OCLC 748686285.

- ^ Bortz, Pablo Gabriel (Winter 2017). "The road they share: the social conflict element in Marx, Keynes and Kalecki". Review of Keynesian Economics. 5 (4): 564 – via Elgar Online.

- ^ Bortz, Pablo Gabriel (Winter 2017). "The road they share: the social conflict element in Marx, Keynes and Kalecki". Review of Keynesian Economics. 5 (4): 564–565 – via Elgar Online.

- ^ Bortz, Pablo Gabriel (Winter 2017). "The road they share: the social conflict element in Marx, Keynes and Kalecki". Review of Keynesian Economics. 5 (4): 570 – via Elgar Online.

- ^ Skidelsky, Robert (January 2010). "The Crisis of Capitalism: Keynes versus Marx". Indian Journal of Industrial Relations. 45 (3): 326.

- ^ Bortz, Pablo Gabriel (Winter 2017). "The road they share: the social conflict element in Marx, Keynes and Kalecki". Review of Keynesian Economics. 5 (4): 563 – via Elgar Online.

- ^ Bortz, Pablo Gabriel (Winter 2017). "The road they share: the social conflict element in Marx, Keynes and Kalecki". Review of Keynesian Economics. 5 (4): 573–574 – via Elgar Online.

- ^ Chang, Ha-Joon (2014). Economics: The User's Guide. London: Penguin Group. pp. 130–131.

- ^ Sardoni, Claudio. (2011). Unemployment, recession and effective demand : the contributions of Marx, Keynes and Kalecki. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-84844-969-5. OCLC 748686285.

- ^ Bortz, Pablo Gabriel (Winter 2017). "The road they share: the social conflict element in Marx, Keynes and Kalecki". Review of Keynesian Economics. 5 (4): 570 – via Elgar Online.