Henry Guy Jenkins III (born June 4, 1958) is an American media scholar and Provost Professor of Communication, Journalism, and Cinematic Arts, a joint professorship at the University of Southern California (USC) Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism and the USC School of Cinematic Arts.[1] He also has a joint faculty appointment with the USC Rossier School of Education.[2] Previously, Jenkins was the Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities as well as co-founder[3] and co-director (with William Uricchio) of the Comparative Media Studies program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He has also served on the technical advisory board at ZeniMax Media, parent company of video game publisher Bethesda Softworks.[4] In 2013, he was appointed to the board that selects the prestigious Peabody Award winners.[5]

Henry Jenkins | |

|---|---|

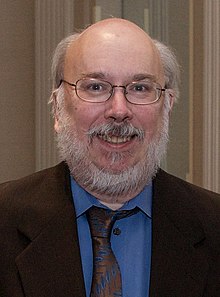

Jenkins at the 2014 Peabody Awards | |

| Born | Henry Guy Jenkins III June 4, 1958 |

| Education | B.A., Political Science & Journalism, M.A., Communication Studies; Ph.D., Communication Arts |

| Alma mater | Georgia State University (BA) University of Iowa (MA) University of Wisconsin–Madison (PhD) |

| Occupation | university professor |

| Years active | 1992–present |

| Employer | University of Southern California |

| Known for | Theories of "transmedia storytelling" and "convergence culture" |

| Title | Provost Professor of Communication, Journalism and Cinematic Arts |

| Spouse | Cynthia |

| Children | 1 |

Jenkins has authored and co-authored over a dozen books including By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism (2016), Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture (2013), Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide (2006), Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture (1992), and What Made Pistachio Nuts?: Early Sound Comedy and the Vaudeville Aesthetic (1989).

Beyond his home country of the United States and the broader English-speaking world, the influence of Jenkins' work (especially his transmedia storytelling and participatory culture work) on media academics as well as practitioners has been notable, for example, across Europe[6] as well as in Brazil[7] and India.[8]

Education and personal life

editJenkins graduated from Georgia State University with a B.A. in Political Science and Journalism. He then earned his M.A. in Communication Studies from the University of Iowa and his Ph.D. in Communication Arts from the University of Wisconsin–Madison.[9] Jenkins's doctoral dissertation, "What Made Pistachio Nuts?": Anarchistic comedy and the vaudeville aesthetic (1989) was supervised by David Bordwell and John Fiske.[10] He and his wife Cynthia Jenkins were housemasters of the Senior House dorm at MIT before leaving MIT for the University of Southern California in May 2009.[11] They have one son, Henry Jenkins IV.[12]

Research fields

editJenkins' academic work has covered a variety of research areas, which can categorized as follows:

Comparative media

editJenkins' media studies scholarship has focussed on several specific forms of media - vaudeville theater, popular cinema, television, comics, and video games - as well as an aesthetic and strategic paradigm, transmedia, which is a framework for designing and communicating stories across many different forms of media. In general, Jenkins' interest in media has concentrated on popular culture forms. In 1999, Jenkins founded the Comparative Media Studies master's program at MIT as an interdisciplinary and applied humanities course which aimed "to integrate the study of contemporary media (film, television, digital systems) with a broad historical understanding of older forms of human expression.... and aims as well for a comparative synthesis that is responsive to the distinctive emerging media culture of the 21st century."[13] The same ethos can be found in Jenkins' research across various forms of media.

Vaudeville and popular cinema

editJenkins' interest in vaudeville theater and popular cinema was an early focus of his research career - his Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Wisconsin explored how the comedy performances of American vaudeville influenced comedy in 1930s sound films, such as those of the Marx Brothers, W.C. Fields, and Eddie Cantor.[14] The dissertation became the basis of his 1992 book What Made Pistachio Nuts?: Early Sound Comedy and the Vaudeville Aesthetic. A key argument of Jenkins' scholarship here was that vaudeville placed a strong emphasis on virtuoso performance and emotional impact which contrasted sharply with the focus of classical Hollywood cinema on character motivation and storytelling. Jenkins' approach was partly inspired by cultural commentators who believed that early cinema was unfairly treated by skeptical commentators of its era because it was a rising new popular culture medium. It was also influenced by scholars of film aesthetics such as David Bordwell. This approach would later help shape Jenkins' scholarly appreciation of video games as another rising popular culture medium attracting much criticism.[15]

Comics studies

editJenkins, long a fan of comics, is also a scholar of the medium and it continues to be one of the key topics of his academic writing and speaking.[16] Jenkins' interest in comics ranges from superhero comics to alternative comics. His academic publications includes work on comics by Brian Michael Bendis, David W. Mack, Art Spiegelman, Basil Wolverton, Dean Motter, amongst others.[17] In December 2015, it was reported by Microsoft Research New England's Social Media Collective (where Jenkins was a visiting scholar at the time), that Jenkins was working on new book focused on comics.[18]

Video game studies

editJenkins' research into video games was influenced by his prior interest in the debates around emerging popular culture media forms as well as his parallel interest in children's culture. Referring to Gilbert Seldes' Seven Lively Arts (1924) which championed the aesthetic merits of popular arts often frowned on by critics who embraced high art to the exclusion of popular art, Jenkins dubbed video games "The New Lively Art" and argued that it was a crucial medium for the growing rise of digital interactive culture.[15]

Jenkins brings a humanist interdisciplinary perspective, drawing on, for instance, cultural studies and literary studies. Examples of video game topics he has written extensively about include the gendering of video game spaces and play experiences,[19] the effects of interactivity on learning and the development of educational video games (this work led to the creation of the Microsoft Games-To-Teach initiative at MIT Comparative Media Studies in 2001 which in 2003 became the Education Arcade initiative, a collaboration with the University of Wisconsin.[20][21]); and game design as a narrative architecture discipline.[22]

Debate on video game violence

editJenkins' role in the video game violence debate has attracted particular public attention. He has been an advocate of a cultural studies approach to understanding media depictions of violence, arguing that "There is no such thing as media violence — at least not in the ways that we are used to talking about it — as something which can be easily identified, counted, and studied in the laboratory. Media violence is not something that exists outside of a specific cultural and social context.".[23] Jenkins has also called for a culturally focused pedagogical response to these issues.[24]

Jenkins' views criticizing theories (such as Jack Thompson's argument) that video games depicting violence cause people to commit real-world violence have also been described in mainstream video game publications such as Next Generation, Electronic Gaming Monthly and Game Informer magazines.[25]

Transmedia

editOne of Jenkins' most well-known concepts has been his "transmedia storytelling", coined in 2003[26] which has become influential not just within academia but also in media arts and advertising/marketing circles and beyond.[27][28][29]

Jenkins has defined transmedia storytelling as so:

Transmedia storytelling represents a process where integral elements of a fiction get dispersed systematically across multiple delivery channels for the purpose of creating a unified and coordinated entertainment experience. Ideally, each medium makes its own unique contribution to the unfolding of the story.[30]

Transmedia storytelling, Jenkins writes, is "the art of world-making", "the process of designing a fictional universe that will sustain franchise development, one that is sufficiently detailed to enable many different stories to emerge but coherent enough so that each story feels like it fits with the others";[31] and crucially, these different stories or story fragments can be spread across many different media platforms encouraging users engaged in the story experience to explore a broader media ecosystem in order to piece together a fuller and deeper understanding of the narrative.

Building on his studies of media fans and participatory culture, Jenkins has emphasized that transmedia storytelling strategies are well-suited for harnessing the collective intelligence of media users.[32] Jenkins has also emphasized that transmedia is not a new phenomena - ancient examples can be found in religion, for example[33] - but the capabilities of new internet and digital technologies for participatory and collective audience engagement across many different media platforms have made the approach more powerful and relevant. Jenkins also emphasises that Transmedia storytelling can be used to create hype for a franchise, in Convergence Culture, he argues that The Matrix-movies, comics and video-games is an example of this phenomenon.[34]

The principles of transmedia storytelling have also been applied to other areas, including transmedia education and transmedia branding, for instance through initiatives led by Jenkins at the USC Annenberg Innovation Lab.[35][36]

Participatory culture

editParticipatory culture has been an encompassing concern of much of Jenkins' scholarly work which has focused on developing media theory and practice principles by which media users are primarily understood as active and creative participants rather than merely as passive consumers and simplistically receptive audiences. This participatory engagement is seen as increasingly important given the enhanced interactive and networked communication capabilities of digital and internet technologies.[37] Jenkins has described the creative social phenomena arising from as participatory culture and is considered one of the main academics specializing in this topic - see, for instance, his 2015 book Participatory Culture in a Networked Era: A Conversation on Youth, Learning, Commerce, and Politics co-authored with Mimi Ito and danah boyd. Jenkins has highlighted the work of media scholar John Fiske as a major influence, particularly in this area of participatory culture.[38]

Jenkins has defined participatory culture as one...

1. With relatively low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement.

2. With strong support for creating and sharing one's creations with others

3. With some type of informal mentorship whereby what is known by the most experienced is passed along to novices

4. Where members believe that their contributions matter

5. Where members feel some degree of social connection with one another (at the least they care what other people think about what they have created). Not every member must contribute, but all must believe they are free to contribute when ready and that what they contribute will be appropriately valued.[39]

Jenkins has also highlighted these key forms of participatory culture:

Affiliations — memberships, formal and informal, in online communities centered around various forms of media (such as Facebook, message boards, metagaming, game clans, or MySpace).

Expressions — producing new creative forms (such as digital sampling, skinning and modding, fan videomaking, fan fiction writing, zines, mash-ups).

Collaborative Problem-solving — working together in teams, formal and informal, to complete tasks and develop new knowledge (such as through Wikipedia, alternative reality gaming, spoiling).

Circulations — Shaping the flow of media (such as podcasting, blogging).[40]

In addition, Jenkins and his collaborators have also identified a range of media literacy skills needed to be effective members of these participatory culture forms[40] - see the New media literacies section below.

Fan studies

editJenkins' work on fan culture arises from his scholarly interests in popular culture and media as well as reflection on his own experiences as a media fan. This also shaped his interest and understanding of participatory culture. Jenkins has described himself as an "aca-fan", a term that first gained currency in the early 1990s [41] that he is credited with helping to popularize more widely (together with Matt Hills' concept of the "fan-academic" in his 2002 work Fan Cultures) to describe an academic who consciously identifies and writes as a fan.[42] Jenkins' 1992 book Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture is regarded as a seminal and foundational work on fan culture which helped establish its legitimacy as a serious topic for academic inquiry, not just in television studies but beyond.[43][44][45] Jenkins' research in Textual Poachers showed how fans construct their own culture by appropriating and remixing—"poaching"—content from mass culture. Through this "poaching", the fans carried out such creative cultural activities as rethinking personal identity issues such as gender and sexuality; writing stories to shift focus onto a media "storyworld's" secondary characters; producing content to expand of the timelines of a storyworld; or filling in missing scenes in the storyworld's official narratives order to better satisfy the fan community.

New media literacies

editBuilding on his work on participatory culture, Jenkins helped lead Project New Media Literacies (NML), one part of a 5-year $50 million research initiative on digital learning funded by the MacArthur Foundation which announced it in 2006.[46] NML's aim was to develop instructional materials designed to help prepare young people to meaningfully participate in the new media environment. As Jenkins explained it: "The NML conceptual framework includes an understanding of challenges, new media literacies, and participatory forms. This framework guides thinking about how to provide adults and youth with the opportunity to develop the skills, knowledge, ethical framework, and self-confidence needed to be full participants in the cultural changes which are taking place in response to the influx of new media technologies, and to explore the transformations and possibilities afforded by these technologies to reshape education."[47] Jenkins introduces a range of social skills and cultural competencies that are fundamental for meaningful participation in a participatory culture. The new media literacies areas given particular definitions by this project (as listed here) include: appropriation (education), collective intelligence, distributed cognition, judgment, negotiation, networking, performance, simulation, transmedia navigation, participation gap, the transparency problem, and the ethics problem.

Convergence culture

editSince his work on fan studies, which led to his 1992 book Textual Poachers, Jenkins' research across various topics can be understood as a continuum with an overall theme. This research theme addresses how groups and communities in online & digital media era participatory culture exercise their own agency. Such agency is exercised by tapping into and combining numerous different media sources and channels, in both officially approved and unapproved ways; when fans or users work as communities to leverage their combined expertise, a collective intelligence process is generated. One of Jenkins' key arguments is that given these cultural phenomena, media convergence is best understood by both media scholars and practitioners as a cultural process, rather than a technological end-point. The key work in Jenkins' development of this argument was his 2006 book Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. As described in this book, convergence culture arises from digital era post-broadcast media landscape where audiences are fragmented by the proliferation of channels and platforms while media users are more empowered than ever before to participate and collaborate – across various channels and platforms – in content creation and dissemination through their access to online networks and digital interactivity.

To help apply the insights of the convergence culture paradigm to industry, he founded the Convergence Culture Consortium - later renamed the Futures of Entertainment Consortium - research initiative in 2005[48] when he was director of Comparative Media Studies program at MIT. Starting in 2006, the Consortium launched the annual Futures of Entertainment conference at MIT for a combined academic and industry audience. In 2010, a sister annual hybrid academia–industry conference, Transmedia Hollywood (renamed Transforming Hollywood in 2014) hosted by USC and UCLA was launched.[49][50][51]

Spreadable media

editBuilding on his work on convergence culture as well as being a direct outgrowth of the conversations between industry and academia fostered by the Convergence Culture Consortium, Jenkins developed the concept of spreadable media, which differs from the theories behind memes and viral media. (This led to his 2013 book Spreadable Media: Creating Meaning and Value in a Networked Culture, co-authored with Sam Ford and Joshua Green). The idea of viral media or memes uses metaphors that leave little room for the deliberate agency while Jenkins' idea of spreadability focuses on the active agency of the ordinary media user in sharing, distributing, creating and/or remixing media content. This focus on the active media user is understood through this concept as increasingly crucial in online/digital era media landscapes where participatory culture is more important than ever, and where the dominance of large-scale media content distribution tightly controlled by corporate or governmental owners has been undermined by the rise of grassroots circulation. The idea of spreadability also contrasts with the idea of "stickiness" in media strategy, which calls for aggregating and holding attention on particular websites or other media channels, Spreadability instead calls for media strategists to embrace how their audiences and users will actively disperse content, using formal and informal networks, not always approved.[52]

Participatory politics (youth civics and activism)

editJenkins has led the Civic Paths and Media, Activism & Participatory Politics (MAPP) initiatives at USC Annenberg since 2009 - work supported in part by a MacArthur Foundation Digital Media & Learning initiative on Youth & Participatory Politics. The focus of these related initiatives has been on studying innovative online and digital media practices in grassroots youth-led civics and activism movements, and builds on Jenkins' earlier work on fan cultures, online communities, and participatory culture. In 2016, By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism, a book co-authored by Jenkins and based on the work of Civic Paths and MAPP, was published.

Children's culture

editOne focus of Jenkins' earlier scholarly career was children's culture, which he has defined as "popular culture produced for, by, and/or about children.... the central arena through which we construct our fantasies about the future and a battleground through which we struggle to express competing ideological agendas."[53] Key topics in Jenkins' children's culture research include children as media consumers, video game studies, the history of child-rearing, the cultural construction of childhood innocence, and the debates over media violence.[53]

Critiques

editJenkins' conception of media convergence, and in particular convergence culture, has inspired much scholarly debate.

In 2011, a special issue of the academic journal Cultural Studies was dedicated to the critical discussion of Jenkins' notion of convergence culture. Titled 'Rethinking "Convergence/Culture," the volume was edited by James Hay and Nick Couldry. Hay and Couldry identify some of the key scholarly critiques of Jenkins' work on convergence culture. They are: an excessive emphasis on the participatory potential of users; an under-appreciation of the inherently corporate logic of convergence; an insufficient consideration of the broader media landscape, with its corresponding power dynamics, in which the user engages with convergence; and an overly optimistic view of the democratic contribution of convergence.[55]

Jenkins published a detailed response in a 2014 issue of the same journal, (also published online by the journal in 2013)—'Rethinking "Rethinking Convergence/Culture"'—countering the critiques laid out in the special issue and clarifying aspects of his work.[56]

Restricted user agency and corporatisation

editA prominent critique in the special Cultural Studies issue criticizing Jenkins' account of convergence culture is that he overstates the power of the user in a convergent media sphere. Jenkins argues that convergence represents a fundamental change in the relationship between producers and consumers of media content. With the transition from supposedly passive to active consumers, the role and agency of consumers have been redefined, with a focus on their ability to engage with media content on their own terms.[57][58] The ability of these 'newly' (the novelty and substantiveness of this empowerment is contested by some critics) empowered audiences to migrate to the content they wanted to engage with was central to Jenkins' claim that convergence is reshaping the cultural logic of media, giving rise to what he termed 'participatory culture'.[59][60] Participatory culture follows from the replacement of the supposedly passive media consumer with a new active media user in an online sphere, no longer governed by the unidirectional dynamic of traditional mass media but by the two-way dynamic of interactivity. These critics interpreted Jenkins' account as a techno-optimist conception of the agency of these users and therefore saw it as highly contentious. Jenkins' account of the dynamic of traditional mass media, and subsequent passivity of the audience is criticised as simplistic because he overemphasises the virtues of interactivity, without considering the real-life power structures in which users exist.[61] In his 2014 response, Jenkins rejected these critics' characterization of his work as techno-optimistic or techno-determinist, stressing that the outcomes of current social and technological change are still to be determined. He also argued that his critics confuse interactivity (pre-programmed into the technology) and participation (emerging from social and cultural factors). Jenkins also countered that there has been a significant level of acknowledging the broader context of offline power structures throughout his scholarship.[56]

Nico Carpentier's argument in the special Cultural Studies issue was that what he sees as Jenkins' "conflation of interaction and participation" is misleading: the opportunities for interaction have increased, but the conglomerated and corporate media environment that convergence has both facilitated and come about in, restricts the capacity of users to genuinely participate in the production, or co-production, of content, due to the media systems' logic of commercial gain.[62] This is in keeping with traditional media business models, which sought a static, easily quantifiable audience to advertise to. In 2012–3, Carpentier and Jenkins had an extended dialogue which clarified that their perspectives actually had much common ground, leading to their co-authoring of a journal article about the distinctions between participation and interaction, and how the two concepts are tied up with power.[63]

Mark Andrejevic also critiqued Jenkins in the 2011 special issue, emphasizing that interactivity can be seen as the provision of detailed user information for exploitation by marketers in the affective economy, that the users themselves willingly submit to.[64] And according to Ginette Verstraete's critique of Jenkins' work in the same issue, the tools of media convergence are inextricably corporate in their purpose and function, even the generation of alternative meanings through co-creation is necessarily contained within a commercial system where "the primary aim is the generation of capital and power through diffraction".[65] Thus, user agency as enabled by media convergence is always already restricted.

This critique of convergence culture as facilitating the disenfranchisement of the user, is taken up by Jack Bratich, who argues that rather than necessarily and inherently facilitating democracy (as Jenkins' position is interpreted by Bratich) convergence may instead achieve the opposite.[66] This emphasis on convergence as restricting the capacities of those who engage with it is also made by Sarah Banet-Weiser in reference to the commodification of creativity.[67] She argues that as convergence is "a crucial element to the logic of capitalism," the democratisation of creative capacity that has been enabled by media convergence, through platforms such as YouTube, serves a commercial purpose.[68] In this account, users become workers and the vast majority of convergence-enabled creative output, by virtue of the profit-driven platforms on which it takes place, can be seen as a byproduct of the profit-imperative. In contrast to Bratich's and Banet-Weiser's perspectives, in Jenkins' 2014 response to the critical special issue, he wrote that "These new platforms and practices potentially enable forms of collective action that are difficult to launch and sustain under a broadcast model, yet these platforms and practices do not guarantee any particular outcome, do not necessarily inculcate democratic values or develop shared ethical norms, do not necessarily respect and value diversity, do not necessarily provide key educational resources, and do not ensure that anyone will listen when groups speak out about injustices they encounter." Jenkins' position is that he has argued consistently - including in his 2006 book Convergence Culture - against any inherent outcomes of convergence.[56]

Limited focus

editCatherine Driscoll, Melissa Gregg, Laurie Ouellette, and Julie Wilson refer to Jenkins' work in the 2011 special issue as part of their challenging of the larger framework of media convergence scholarship. They argue that the willing submission of the user to the corporate interests fuelling media convergence is also gendered as the logic of convergence, which is, to a large extent, informed by the logic of capitalism, albeit in an online environment, perpetuating the ongoing exploitation of women through a replication of the 'free' labour built into social expectations of women.[69][70] And Richard Maxwell & Toby Miller in the same issue also reference Jenkins' work to critique the broader discourse of media convergence, arguing that the logic of convergence is one of ceaseless growth and innovation that inevitably preferences commercial over individual interests.[71](In Jenkins' 2014 response, he counters that throughout his scholarship he has emphasized collective agency not individual agency[56]). Furthermore, Maxwell & Miller argue prevailing discussions of convergence have attended to the micro level of technological progress over the macro level of rampant economic exploitation, through concepts like 'playbour' (labour freely provided by users as they interact with the online world) resulting in a dominant focus on the Global North that ignores the often abhorrent material conditions of workers in the Global South who fuel the ongoing proliferation of digital capitalism.

Democratic contribution

editIn his contribution to the special Cultural Studies issue critiquing Jenkins' work on convergence, Graeme Turner argued for the need to be wary of any overtly optimistic accounts of the impacts of convergence culture.[72] Although there is no denying, he argues, that the idea of convergence has "its heart in the right place," seeking the "empowerment for the individual ... the democratizing potential of new media, and ... [the desire to] achieve something more socially useful than commercial success," there are no guarantees that any of this is achievable.[73] In his 2014 response to such criticism, Jenkins acknowledged that "My experiences at intervention have tempered some of the exuberance people have identified in Convergence Culture with a deeper understanding of how difficult it will be to make change happen....I have also developed a deeper appreciation for all of the systemic and structural challenges we face in changing the way established institutions operate, all of the outmoded and entrenched thinking which make even the most reasonable reform of established practices difficult to achieve..."[56]

"More participatory culture"

editIn Jenkins' 2014 response to the 2011 special issue, he countered arguments such as Turner's above by stating that while we may not yet know the full extent of the impact of convergence, we are "better off remaining open to new possibilities and emerging models". However, Jenkins agreed too that his original conception of participatory culture could be overly optimistic about the possibilities of convergence.[56] He also suggested that the revised phrasing of 'more participatory culture,' which acknowledges the radical potential of convergence without pessimistically characterising it as a tool of "consumer capitalism [that] will always fully contain all forms of grassroots resistance". Such pessimism, in this view, would repeat the determinist error of the overly optimistic account. As Jenkins wrote in his 2014 response: "Today, I am much more likely to speak about a push toward a more participatory culture, acknowledging how many people are still excluded from even the most minimal opportunities for participation within networked culture, and recognizing that new grassroots tactics are confronting a range of corporate strategies which seek to contain and commodify the popular desire for participation. As a consequence, elites still exert a more powerful influence on political decision-making than grassroots networks, even if we are seeing new ways to assert alternative perspectives into the decision-making process."[56]

Books published

edit- Jenkins, Henry (1992). What Made Pistachio Nuts?: Early Sound Comedy and the Vaudeville Aesthetic. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-07855-9.

- Jenkins, Henry (1992). Textual Poachers: Television Fans & Participatory Culture. Studies in culture and communication. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-90571-8.

- Jenkins, Henry (ed. with Kristine Brunovska Karnick) (1994). Classical Hollywood Comedy. American Film Institute Film Readers. New York: Routledge, Chapman and Hall. ISBN 978-0-415-90639-5.

- Tulloch, John; Jenkins, Henry (1995). Science Fiction Audiences: Doctor Who, Star Trek and Their Followers. London: Routledge, Chapman and Hall. ISBN 978-0-4150-6141-4.

- Jenkins, Henry (ed. with Justine Cassell) (1998). From Barbie to Mortal Kombat: Gender and Computer Games. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-2620-3258-2.

- Jenkins, Henry (1998). The Children's Culture Reader. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-4231-0.

- Jenkins, Henry (ed. with Tara McPherson and Jane Shattuc) (2002). Hop on Pop: The Politics and Pleasures of Popular Culture. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2737-0.

- Thorburn, David and Henry Jenkins (Eds.) (2003). Rethinking Media Change: The Aesthetics of Transition. Media in Transition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-20146-9.

- Jenkins, Henry and David Thorburn (Eds.) (2003). Democracy and New Media. Media in Transition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-10101-1.

- Jenkins, Henry (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-4281-5.

- Jenkins, Henry (2006). Fans, Bloggers, and Gamers: Exploring Participatory Culture. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-4284-6.

- Jenkins, Henry (2007). The Wow Climax: Tracing the Emotional Impact of Popular Culture. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-4282-2.

- Jenkins, Henry (with Ravi Purushotma, Margaret Weigel, Katie Clinton, and Alice J. Robison) (2009), Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century, Cambridge: MIT Press, ISBN 9780262513623

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jenkins, Henry; Ford, Sam; Green, Joshua (2013), Spreadable Media: Creating Meaning and Value in a Networked Culture, New York: New York University Press, ISBN 978-0-8147-4350-8

- Jenkins, Henry; Kelley, Wyn (with Katie Clinton, Jenna McWilliams, Ricardo Pitts-Wiley and Erin Reilly) (2013), Reading in a Participatory Culture: Remixing Moby-Dick for the English Literature Classroom, New York: Teachers College Press, ISBN 9780262513623

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jenkins, Henry; Ito, Mizuko; boyd, danah (2015), Participatory Culture in a Networked Era: A Conversation on Youth, Learning, Commerce, and Politics, Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, ISBN 978-0-7456-6070-7

- Jenkins, Henry; Shresthova, Sangita; Gamber-Thompson, Liana; Kligler-Vilenchik, Neta; Zimmerman, Arely (2016), By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism, Connected Youth and Digital Futures, New York: New York University Press, ISBN 978-1-4798-9998-2

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Henry Jenkins - USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism".

- ^ "Profile - Rossier School of Education".

- ^ Keith Stuart (2008-10-08). "Henry Jenkins on the eight biggest game myths". the Guardian.

- ^ "ZeniMax Media Profile-Technical Advisory Board". ZeniMax.com. 2001. Archived from the original on October 8, 2001. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- ^ "Jenkins named to George Foster Peabody Awards Board - Rossier School of Education". Rossier School of Education. 2013-10-28. Archived from the original on 2019-01-02. Retrieved 2017-04-26.

- ^ "Au Revoir: Heading to Europe". May 2012.

- ^ "My Big Brazilian [sic] Adventure". 7 June 2010.

- ^ "Why I Went to India…". 2 September 2015.

- ^ "Who the &%&# Is Henry Jenkins?". 10 November 2023.

- ^ Jenkins III, Henry Guy (1989). "What Made Pistachio Nuts?": Anarchistic comedy and the vaudeville aesthetic (PhD Communication Art thesis). The University of Wisconsin. ProQuest 303791532.

Film studies; Motion pictures; Theater

- ^ Natasha Nath. "Jag Patel, Antony Donovan Move In to Senior House - The Tech". Archived from the original on 2010-06-18. Retrieved 2016-01-30.

- ^ "The World of Reality Fiction". 18 September 2006.

- ^ "MIT Reports to the President 1998-99 / COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES".

- ^ "Youtube and the Vaudeville Aesthetic". 19 November 2006.

- ^ a b "Henry Jenkins - Games, the New Lively Art".

- ^ ""henry jenkins" comics - Google Search".

- ^ "comics Bendis OR Mack OR Spiegelman OR Wolverton OR Motter author:"H Jenkins" - Google Scholar".

- ^ Gillespie, Tarleton (18 December 2015). "Henry Jenkins, on "Comics and Stuff"".

- ^ Egenfeldt-Nielsen, Smith, ToscaUnderstanding Video Games: The Essential Introduction. New York and London: Taylor and Francis Group, 2008

- ^ "iCampus Project: Games-to-Teach".

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-20. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-07-29. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "A Few Thoughts on Media Violence…". 24 April 2007.

- ^ "A Pedagogical Response to the Aurora Shootings: 10 Critical Questions about Fictional Representations of Violence". 22 July 2012.

- ^ "Videogames are good for you!". Next Generation (29): 8–13, 161, 162. May 1997.

- ^ Jenkins, Henry. "Transmedia Storytelling".

- ^ "Transmedia and the new art of storytelling". The Daily Dot. 23 October 2012.

- ^ "In Ridley Scott's 'Prometheus,' the Advertising Is Part of the Picture". 23 March 2012.

- ^ "5 Lessons For Storytellers From The Transmedia World". 7 June 2012.

- ^ "Transmedia Storytelling 101". 21 March 2007.

- ^ Jenkins, Henry Convergence Culture: Where old and new media collide. New York: New York University Press, 2006

- ^ "Jenkins on Collective Intelligence and Convergence Culture - Chapter 1: Literacies on a Human Scale - Literacies - New Learning".

- ^ Lacasa, P. (18 September 2013). Learning in Real and Virtual Worlds: Commercial Video Games as Educational Tools. Springer. ISBN 9781137312051 – via Google Books.

- ^ Jenkins, Henry, 1958-. Convergence culture : where old and new media collide. New York. ISBN 978-0-8147-4368-3. OCLC 829025920.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ anonymous. "T is for Transmedia - Annenberg Innovation Lab". Archived from the original on 2016-04-17. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- ^ anonymous. "Transmedia Branding - Annenberg Innovation Lab". Archived from the original on 2016-03-30. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- ^ "Understanding the Participatory Culture of the Web: An Interview with Henry Jenkins - The Signal". 24 July 2014.

- ^ "John Fiske: Now and The Future". 16 June 2010.

- ^ "Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century (Part One)". 19 October 2006.

- ^ a b Jenkins, Henry (2009). "Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education For the 21st Century". Building the Field of Digital Media and Learning. ISBN 9780262513623.

- ^ Roach, Catherine M. (31 March 2016). Happily Ever After: The Romance Story in Popular Culture. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253020529 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Acafan - Fanlore".

- ^ Barker, Chris (12 December 2011). Cultural Studies: Theory and Practice. SAGE. ISBN 9781446260432 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Fans and Fan Culture : Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology : Blackwell Reference Online". Archived from the original on 2017-10-16. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- ^ Scott, Suzanne (10 December 2014). "Understanding fandom: An introduction to the study of media fan culture, by Mark Duffett". Transformative Works and Cultures. 20. doi:10.3983/twc.2015.0656.

- ^ "MacArthur Investing $50 Million In Digital Learning — MacArthur Foundation".

- ^ Jenkins, Henry. "Our Methods". USC Annenberg School of Communication and Journalism. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ "Henry Jenkins on 'Spreadable Media,' why fans rule, and why 'The Walking Dead' lives".

- ^ "Don't Miss Transmedia, Hollywood Conference March 16". 3 March 2010.

- ^ "Further Information About Transforming Hollywood: The Future of Television". 14 March 2014.

- ^ "Futures of Entertainment - Transforming Hollywood".

- ^ NY, CHIPS. "Spreadable Media".

- ^ a b "Henry Jenkins - Children's Culture".

- ^ "How Content Gains Meaning and Value in the Era of Spreadable Media". June 18, 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ Hay, James; Couldry, Nick (2011). "Rethinking Convergence/Culture: An Introduction". Cultural Studies. 25 (4–5): 473–486. doi:10.1080/09502386.2011.600527. S2CID 142908522.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jenkins, Henry (2014). "Rethinking "Rethinking Convergence/Culture"". Cultural Studies. 28 (2): 267–297. doi:10.1080/09502386.2013.801579. S2CID 144101343.

- ^ Jenkins, Henry (2004). "The Cultural Logic of Media Convergence". International Journal of Cultural Studies. 7 (1): 37. doi:10.1177/1367877904040603. S2CID 145699401.

- ^ Deuze, Mark. Media Work. Cambridge: Polity. p. 74.

- ^ Jenkins, Henry (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780814742815.

- ^ Jenkins, Henry (2014). "Rethinking 'Rethinking Convergence/Culture'". Cultural Studies. 28 (2): 268. doi:10.1080/09502386.2013.801579. S2CID 144101343.

- ^ Hay, James; Couldry, Nick (2011). "Rethinking Convergence/Culture". Cultural Studies. 25 (4–5): 473–486. doi:10.1080/09502386.2011.600527. S2CID 142908522.

- ^ Carpentier, Nico (2011). "Contextualising Author-Audience Convergences". Cultural Studies. 25 (4–5): 529. doi:10.1080/09502386.2011.600537. S2CID 54766187.

- ^ Jenkins, Henry; Carpentier, Nico (2013). "Theorizing participatory intensities: A conversation about participation and politics". Convergence. 19 (3): 265 [1]. doi:10.1177/1354856513482090. S2CID 143448444.

- ^ Andrejevic, Mark (2011). "The Work that Affective Economics Does". Cultural Studies. 25 (4–5): 604–620. doi:10.1080/09502386.2011.600551. S2CID 154418707.

- ^ Verstraete, Ginette (2011). "The Politics of Convergence". Cultural Studies. 25 (4–5): 542. doi:10.1080/09502386.2011.600544. S2CID 143544327.

- ^ Bratich, Jack (2011). "User-Generated Discontent: Convergence, Polemology, and Dissent'". Cultural Studies. 25 (4–5). doi:10.1080/09502386.2011.600552. S2CID 153261808.

- ^ Banet-Weiser, Sarah (2011). "Convergence on the Street: Re-thinking the Authentic/Commercial Binary'". Cultural Studies. 25 (4–5). doi:10.1080/09502386.2011.600553. S2CID 142859601.

- ^ Banet-Weiser, Sarah (2011). "Convergence on the Street: Re-thinking the Authentic/Commercial Binary". Cultural Studies. 25 (4–5): 654. doi:10.1080/09502386.2011.600553. S2CID 142859601.

- ^ Driscoll, Catherine; Gregg, Melissa (2011). "Convergence Culture and the Legacy of Feminist Cultural Studies". Cultural Studies. 25 (4–5): 566–584. doi:10.1080/09502386.2011.600549. S2CID 144257756.

- ^ Ouelette, Laurie; Wilson, Julie (2011). "Women's Work: Affective Labour and Convergence Culture". Cultural Studies. 25 (4–5). doi:10.1080/09502386.2011.600546. S2CID 142738154.

- ^ Maxwell, Richard; Miller, Toby (2011). "Old, New and Middle-Aged Media Convergence". Cultural Studies. 25 (4–5): 595. doi:10.1080/09502386.2011.600550. S2CID 145153660.

- ^ Turner, Graeme (2011). "Surrendering the Space: Convergence Culture, Cultural Studies and the Curriculum". Cultural Studies. 25 (4–5). doi:10.1080/09502386.2011.600556. S2CID 143373733.

- ^ Turner, Graeme (2011). "Surrendering the Space: Convergence Culture, Cultural Studies and the Curriculum". Cultural Studies. 25 (4–5): 696. doi:10.1080/09502386.2011.600556. S2CID 143373733.

External links

edit- Official website and blog

- Comparative Media Studies, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Foreword to the Italian Edition of Convergence Culture (English translation)

- How Content Gains Meaning in the Age of Spreadable Media, talk given by Henry Jenkins in Bologna, Italy, on June 27, 2012. Streaming audio with a written introduction and summary by Wu Ming 1 (in Italian).

- Henry Jenkins Playlist Appearance on WMBR's Dinnertime Sampler Archived 2011-05-04 at the Wayback Machine radio show January 15, 2003

- Henry Jenkins Complete Freedom of Movement: Video Games as Gendered Play Spaces

- MacArthur Foundation profile

- Henry Jenkins Frontline interview on schools and technology

- Discussions at WGBH Studios, from the web-only interview series WGBH One Guest

- Video games as art Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Participatory media Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Citizen journalism Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine