Zirconium is a chemical element; it has symbol Zr and atomic number 40. First identified in 1789, isolated in impure form in 1824, and manufactured at scale by 1925, pure zirconium is a lustrous transition metal with a greyish-white color that closely resembles hafnium and, to a lesser extent, titanium. It is solid at room temperature, ductile, malleable and corrosion-resistant. The name zirconium is derived from the name of the mineral zircon, the most important source of zirconium. The word is related to Persian zargun (zircon; zar-gun, "gold-like" or "as gold").[11] Besides zircon, zirconium occurs in over 140 other minerals, including baddeleyite and eudialyte; most zirconium is produced as a byproduct of minerals mined for titanium and tin.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zirconium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /zɜːrˈkoʊniəm/ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery white | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Zr) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

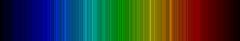

| Zirconium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 40 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Kr] 4d2 5s2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 10, 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 2125 K (1852 °C, 3365 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 4650 K (4377 °C, 7911 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (at 20° C) | 6.505 g/cm3[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 5.8 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 14 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 591 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 25.36 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | common: +4 −2,[4] 0,[5] +1,[6] +2,[7][8] +3[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.33 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 160 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 175±7 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | hexagonal close-packed (hcp) (hP2) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lattice constants | a = 323.22 pm c = 514.79 pm (at 20 °C)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 5.69×10−6/K (at 20 °C)[3][a] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 22.6 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 421 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic[9] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 88 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 33 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 91.1 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 3800 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.34 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 5.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 820–1800 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 638–1880 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-67-7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | after zircon, zargun زرگون meaning "gold-colored". | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Martin Heinrich Klaproth (1789) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First isolation | Jöns Jakob Berzelius (1824) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of zirconium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Zirconium forms a variety of inorganic compounds, such as zirconium dioxide, and organometallic compounds, such as zirconocene dichloride. Five isotopes occur naturally, four of which are stable. The metal and its alloys are mainly used as a refractory and opacifier; pure zirconium plays a vital role in the construction of nuclear reactors due to strong resistance to corrosion and low nuclear reaction cross section, and in space vehicles and turbine blades where high heat resistance is necessary. Zirconium also finds uses in flashbulbs, biomedical applications such as dental implants and prosthetics, deodorant, and water purification systems.

Zirconium compounds have no known biological role, though the element is widely distributed in nature and appears in small quantities in biological systems without adverse effects. There is no indication of zirconium as a carcinogen. The main hazards posed by zirconium are flammability in powder form and irritation of the eyes.

Characteristics

editZirconium is a lustrous, greyish-white, soft, ductile, malleable metal that is solid at room temperature, though it is hard and brittle at lesser purities.[12] In powder form, zirconium is highly flammable, but the solid form is much less prone to ignition. Zirconium is highly resistant to corrosion by alkalis, acids, salt water and other agents.[13] However, it will dissolve in hydrochloric and sulfuric acid, especially when fluorine is present.[14] Alloys with zinc are magnetic at less than 35 K.[13]

The melting point of zirconium is 1855 °C (3371 °F), and the boiling point is 4409 °C (7968 °F).[13] Zirconium has an electronegativity of 1.33 on the Pauling scale. Of the elements within the d-block with known electronegativities, zirconium has the fourth lowest electronegativity after hafnium, yttrium, and lutetium.[15]

At room temperature zirconium exhibits a hexagonally close-packed crystal structure, α-Zr, which changes to β-Zr, a body-centered cubic crystal structure, at 863 °C. Zirconium exists in the β-phase until the melting point.[16]

Isotopes

editNaturally occurring zirconium is composed of five isotopes. 90Zr, 91Zr, 92Zr and 94Zr are stable, although 94Zr is predicted to undergo double beta decay (not observed experimentally) with a half-life of more than 1.10×1017 years. 96Zr has a half-life of 2.34×1019 years, and is the longest-lived radioisotope of zirconium. Of these natural isotopes, 90Zr is the most common, making up 51.45% of all zirconium. 96Zr is the least common, comprising only 2.80% of zirconium.[10]

Thirty-three artificial isotopes of zirconium have been synthesized, ranging in atomic mass from 77 to 114.[10][17] 93Zr is the longest-lived artificial isotope, with a half-life of 1.61×106 years. Radioactive isotopes at or above mass number 93 decay by electron emission, whereas those at or below 89 decay by positron emission. The only exception is 88Zr, which decays by electron capture.[10]

Thirteen isotopes of zirconium also exist as metastable isomers: 83m1Zr, 83m2Zr, 85mZr, 87mZr, 88mZr, 89mZr, 90m1Zr, 90m2Zr, 91mZr, 97mZr, 98mZr, 99mZr, and 108mZr. Of these, 97mZr has the shortest half-life at 104.8 nanoseconds. 89mZr is the longest lived with a half-life of 4.161 minutes.[10]

Occurrence

editZirconium has a concentration of about 130 mg/kg within the Earth's crust and about 0.026 μg/L in sea water. It is the 18th most abundant element in the crust.[18] It is not found in nature as a native metal, reflecting its intrinsic instability with respect to water. The principal commercial source of zirconium is zircon (ZrSiO4), a silicate mineral,[12] which is found primarily in Australia, Brazil, India, Russia, South Africa and the United States, as well as in smaller deposits around the world.[19] As of 2013, two-thirds of zircon mining occurs in Australia and South Africa.[20] Zircon resources exceed 60 million tonnes worldwide[21] and annual worldwide zirconium production is approximately 900,000 tonnes.[18] Zirconium also occurs in more than 140 other minerals, including the commercially useful ores baddeleyite and eudialyte.[22]

Zirconium is relatively abundant in S-type stars, and has been detected in the sun and in meteorites. Lunar rock samples brought back from several Apollo missions to the moon have a high zirconium oxide content relative to terrestrial rocks.[23]

EPR spectroscopy has been used in investigations of the unusual 3+ valence state of zirconium. The EPR spectrum of Zr3+, which has been initially observed as a parasitic signal in Fe‐doped single crystals of ScPO4, was definitively identified by preparing single crystals of ScPO4 doped with isotopically enriched (94.6%)91Zr. Single crystals of LuPO4 and YPO4 doped with both naturally abundant and isotopically enriched Zr have also been grown and investigated.[24]

Production

editOccurrence

editZirconium is a by-product formed after mining and processing of the titanium minerals ilmenite and rutile, as well as tin mining.[25] From 2003 to 2007, while prices for the mineral zircon steadily increased from $360 to $840 per tonne, the price for unwrought zirconium metal decreased from $39,900 to $22,700 per ton. Zirconium metal is much more expensive than zircon because the reduction processes are costly.[21]

Collected from coastal waters, zircon-bearing sand is purified by spiral concentrators to separate lighter materials, which are then returned to the water because they are natural components of beach sand. Using magnetic separation, the titanium ores ilmenite and rutile are removed.[26]

Most zircon is used directly in commercial applications, but a small percentage is converted to the metal. Most Zr metal is produced by the reduction of the zirconium(IV) chloride with magnesium metal in the Kroll process.[13] The resulting metal is sintered until sufficiently ductile for metalworking.[19]

Separation of zirconium and hafnium

editCommercial zirconium metal typically contains 1–3% of hafnium,[27] which is usually not problematic because the chemical properties of hafnium and zirconium are very similar. Their neutron-absorbing properties differ strongly, however, necessitating the separation of hafnium from zirconium for nuclear reactors.[28] Several separation schemes are in use.[27] The liquid-liquid extraction of the thiocyanate-oxide derivatives exploits the fact that the hafnium derivative is slightly more soluble in methyl isobutyl ketone than in water. This method accounts for roughly two-thirds of pure zirconium production,[29] though other methods are being researched;[30] for instance, in India, a TBP-nitrate solvent extraction process is used for the separation of zirconium from other metals.[31] Zr and Hf can also be separated by fractional crystallization of potassium hexafluorozirconate (K2ZrF6), which is less soluble in water than the analogous hafnium derivative. Fractional distillation of the tetrachlorides, also called extractive distillation, is also used.[30][32]

Vacuum arc melting, combined with the use of hot extruding techniques and supercooled copper hearths, is capable of producing zirconium that has been purified of oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon.[33]

Hafnium must be removed from zirconium for nuclear applications because hafnium has a neutron absorption cross-section 600 times greater than zirconium.[34] The separated hafnium can be used for reactor control rods.[35]

Compounds

editLike other transition metals, zirconium forms a wide range of inorganic compounds and coordination complexes.[36] In general, these compounds are colourless diamagnetic solids wherein zirconium has the oxidation state +4. Some organometallic compounds are considered to have Zr(II) oxidation state.[7] Non-equilibrium oxidation states between 0 and 4 have been detected during zirconium oxidation.[8]

Oxides, nitrides, and carbides

editThe most common oxide is zirconium dioxide, ZrO2, also known as zirconia. This clear to white-coloured solid has exceptional fracture toughness (for a ceramic) and chemical resistance, especially in its cubic form.[37] These properties make zirconia useful as a thermal barrier coating,[38] although it is also a common diamond substitute.[37] Zirconium monoxide, ZrO, is also known and S-type stars are recognised by detection of its emission lines.[39]

Zirconium tungstate has the unusual property of shrinking in all dimensions when heated, whereas most other substances expand when heated.[13] Zirconyl chloride is one of the few water-soluble zirconium complexes, with the formula [Zr4(OH)12(H2O)16]Cl8.[36]

Zirconium carbide and zirconium nitride are refractory solids. Both are highly corrosion-resistant and find uses in high-temperature resistant coatings and cutting tools.[40] Zirconium hydride phases are known to form when zirconium alloys are exposed to large quantities of hydrogen over time; due to the brittleness of zirconium hydrides relative to zirconium alloys, the mitigation of zirconium hydride formation was highly studied during the development of the first commercial nuclear reactors, in which zirconium carbide was a frequently used material.[41]

Lead zirconate titanate (PZT) is the most commonly used piezoelectric material, being used as transducers and actuators in medical and microelectromechanical systems applications.[42]

Halides and pseudohalides

editAll four common halides are known, ZrF4, ZrCl4, ZrBr4, and ZrI4. All have polymeric structures and are far less volatile than the corresponding titanium tetrahalides; they find applications in the formation of organic complexes such as zirconocene dichloride.[43] All tend to hydrolyse to give the so-called oxyhalides and dioxides.[27]

Fusion of the tetrahalides with additional metal gives lower zirconium halides (e.g. ZrCl3). These adopt a layered structure, conducting within the layers but not perpendicular thereto.[44]

The corresponding tetraalkoxides are also known. Unlike the halides, the alkoxides dissolve in nonpolar solvents. Dihydrogen hexafluorozirconate is used in the metal finishing industry as an etching agent to promote paint adhesion.[45]

Organic derivatives

editOrganozirconium chemistry is key to Ziegler–Natta catalysts, used to produce polypropylene. This application exploits the ability of zirconium to reversibly form bonds to carbon. Zirconocene dibromide ((C5H5)2ZrBr2), reported in 1952 by Birmingham and Wilkinson, was the first organozirconium compound.[46] Schwartz's reagent, prepared in 1970 by P. C. Wailes and H. Weigold,[47] is a metallocene used in organic synthesis for transformations of alkenes and alkynes.[48]

Many complexes of Zr(II) are derivatives of zirconocene,[43] one example being (C5Me5)2Zr(CO)2.

History

editThe zirconium-containing mineral zircon and related minerals (jargoon, jacinth, or hyacinth, ligure) were mentioned in biblical writings.[13][28] The mineral was not known to contain a new element until 1789,[49] when Klaproth analyzed a jargoon from the island of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). He named the new element Zirkonerde (zirconia),[13] related to the Persian zargun (zircon; zar-gun, "gold-like" or "as gold").[11] Humphry Davy attempted to isolate this new element in 1808 through electrolysis, but failed.[12] Zirconium metal was first obtained in an impure form in 1824 by Berzelius by heating a mixture of potassium and potassium zirconium fluoride in an iron tube.[13]

The crystal bar process (also known as the Iodide Process), discovered by Anton Eduard van Arkel and Jan Hendrik de Boer in 1925, was the first industrial process for the commercial production of metallic zirconium. It involves the formation and subsequent thermal decomposition of zirconium tetraiodide (ZrI4), and was superseded in 1945 by the much cheaper Kroll process developed by William Justin Kroll, in which zirconium tetrachloride (ZrCl4) is reduced by magnesium:[19][50]

Applications

editApproximately 900,000 tonnes of zirconium ores were mined in 1995, mostly as zircon.[27]

Most zircon is used directly in high-temperature applications. Because it is refractory, hard, and resistant to chemical attack, zircon finds many applications. Its main use is as an opacifier, conferring a white, opaque appearance to ceramic materials. Because of its chemical resistance, zircon is also used in aggressive environments, such as moulds for molten metals.[27]

Zirconium dioxide (ZrO2) is used in laboratory crucibles, in metallurgical furnaces, and as a refractory material[13] Because it is mechanically strong and flexible, it can be sintered into ceramic knives and other blades.[51] Zircon (ZrSiO4) and cubic zirconia (ZrO2) are cut into gemstones for use in jewelry. Zirconium dioxide is a component in some abrasives, such as grinding wheels and sandpaper.[49] Zircon is also used in dating of rocks from about the time of the Earth's formation through the measurement of its inherent radioisotopes, most often uranium and lead.[52]

A small fraction of the zircon is converted to the metal, which finds various niche applications. Because of zirconium's excellent resistance to corrosion, it is often used as an alloying agent in materials that are exposed to aggressive environments, such as surgical appliances, light filaments, and watch cases. The high reactivity of zirconium with oxygen at high temperatures is exploited in some specialised applications such as explosive primers and as getters in vacuum tubes.[53] Zirconium powder is used as a degassing agent in electron tubes, while zirconium wire and sheets are utilized for grid and anode supports.[54][55] Burning zirconium was used as a light source in some photographic flashbulbs. Zirconium powder with a mesh size from 10 to 80 is occasionally used in pyrotechnic compositions to generate sparks. The high reactivity of zirconium leads to bright white sparks.[56]

Nuclear applications

editCladding for nuclear reactor fuels consumes about 1% of the zirconium supply,[27] mainly in the form of zircaloys. The desired properties of these alloys are a low neutron-capture cross-section and resistance to corrosion under normal service conditions.[19][13] Efficient methods for removing the hafnium impurities were developed to serve this purpose.[28]

One disadvantage of zirconium alloys is the reactivity with water, producing hydrogen, leading to degradation of the fuel rod cladding:[57]

Hydrolysis is very slow below 100 °C, but rapid at temperature above 900 °C. Most metals undergo similar reactions. The redox reaction is relevant to the instability of fuel assemblies at high temperatures.[58] This reaction occurred in the reactors 1, 2 and 3 of the Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant (Japan) after the reactor cooling was interrupted by the earthquake and tsunami disaster of March 11, 2011, leading to the Fukushima I nuclear accidents. After venting the hydrogen in the maintenance hall of those three reactors, the mixture of hydrogen with atmospheric oxygen exploded, severely damaging the installations and at least one of the containment buildings.[59]

Zirconium is a constituent of uranium zirconium hydrides, nuclear fuels used in research reactors.[60]

Space and aeronautic industries

editMaterials fabricated from zirconium metal and ZrO2 are used in space vehicles where resistance to heat is needed.[28]

High temperature parts such as combustors, blades, and vanes in jet engines and stationary gas turbines are increasingly being protected by thin ceramic layers and/or paintable coatings, usually composed of a mixture of zirconia and yttria.[61]

Zirconium is also used as a material of first choice for hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) tanks, propellant lines, valves, and thrusters, in propulsion space systems such as these equipping the Sierra Space's Dream Chaser spaceplane[62] where the thrust is provided by the combustion of kerosene and hydrogen peroxide, a powerful, but unstable, oxidizer. The reason is that zirconium has an excellent corrosion resistance to H2O2 and, above all, do not catalyse its spontaneous self-decomposition as the ions of many transition metals do.[62][63]

Medical uses

editZirconium-bearing compounds are used in many biomedical applications, including dental implants and crowns, knee and hip replacements, middle-ear ossicular chain reconstruction, and other restorative and prosthetic devices.[64]

Zirconium binds urea, a property that has been utilized extensively to the benefit of patients with chronic kidney disease.[64] For example, zirconium is a primary component of the sorbent column dependent dialysate regeneration and recirculation system known as the REDY system, which was first introduced in 1973. More than 2,000,000 dialysis treatments have been performed using the sorbent column in the REDY system.[65] Although the REDY system was superseded in the 1990s by less expensive alternatives, new sorbent-based dialysis systems are being evaluated and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Renal Solutions developed the DIALISORB technology, a portable, low water dialysis system. Also, developmental versions of a Wearable Artificial Kidney have incorporated sorbent-based technologies.[66]

Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate is used by mouth in the treatment of hyperkalemia. It is a selective sorbent designed to trap potassium ions in preference to other ions throughout the gastrointestinal tract.[67]

Mixtures of monomeric and polymeric Zr4+ and Al3+ complexes with hydroxide, chloride and glycine, called aluminium zirconium glycine salts, are used in a preparation as an antiperspirant in many deodorant products. It has been used since the early 1960s, as it was determined more efficacious as an antiperspirant than contemporary active ingredients such as aluminium chlorohydrate.[68]

Defunct applications

editZirconium carbonate (3ZrO2·CO2·H2O) was used in lotions to treat poison ivy but was discontinued because it occasionally caused skin reactions.[12]

Safety

edit| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Although zirconium has no known biological role, the human body contains, on average, 250 milligrams of zirconium, and daily intake is approximately 4.15 milligrams (3.5 milligrams from food and 0.65 milligrams from water), depending on dietary habits.[69] Zirconium is widely distributed in nature and is found in all biological systems, for example: 2.86 μg/g in whole wheat, 3.09 μg/g in brown rice, 0.55 μg/g in spinach, 1.23 μg/g in eggs, and 0.86 μg/g in ground beef.[69] Further, zirconium is commonly used in commercial products (e.g. deodorant sticks, aerosol antiperspirants) and also in water purification (e.g. control of phosphorus pollution, bacteria- and pyrogen-contaminated water).[64]

Short-term exposure to zirconium powder can cause irritation, but only contact with the eyes requires medical attention.[70] Persistent exposure to zirconium tetrachloride results in increased mortality in rats and guinea pigs and a decrease of blood hemoglobin and red blood cells in dogs. However, in a study of 20 rats given a standard diet containing ~4% zirconium oxide, there were no adverse effects on growth rate, blood and urine parameters, or mortality.[71] The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) legal limit (permissible exposure limit) for zirconium exposure is 5 mg/m3 over an 8-hour workday. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) recommended exposure limit (REL) is 5 mg/m3 over an 8-hour workday and a short term limit of 10 mg/m3. At levels of 25 mg/m3, zirconium is immediately dangerous to life and health.[72] However, zirconium is not considered an industrial health hazard.[64] Furthermore, reports of zirconium-related adverse reactions are rare and, in general, rigorous cause-and-effect relationships have not been established.[64] No evidence has been validated that zirconium is carcinogenic[73] or genotoxic.[74]

Among the numerous radioactive isotopes of zirconium, 93Zr is among the most common. It is released as a product of nuclear fission of 235U and 239Pu, mainly in nuclear power plants and during nuclear weapons tests in the 1950s and 1960s. It has a very long half-life (1.53 million years), its decay emits only low energy radiations, and it is not considered particularly hazardous.[75]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ The thermal expansion of a zirconium crystal is anisotropic: the parameters (at 20 °C) for each crystal axis are αa = 4.91×10−6/K, αc = 7.26×10−6/K, and αaverage = αV/3 = 5.69×10−6/K.[3]

References

edit- ^ "Standard Atomic Weights: Zirconium". CIAAW. 2024.

- ^ Prohaska, Thomas; Irrgeher, Johanna; Benefield, Jacqueline; Böhlke, John K.; Chesson, Lesley A.; Coplen, Tyler B.; Ding, Tiping; Dunn, Philip J. H.; Gröning, Manfred; Holden, Norman E.; Meijer, Harro A. J. (2022-05-04). "Standard atomic weights of the elements 2021 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. doi:10.1515/pac-2019-0603. ISSN 1365-3075.

- ^ a b c d Arblaster, John W. (2018). Selected Values of the Crystallographic Properties of Elements. Materials Park, Ohio: ASM International. ISBN 978-1-62708-155-9.

- ^ Zr(–2) is known in Zr(CO)2−6; see John E. Ellis (2006). "Adventures with Substances Containing Metals in Negative Oxidation States". Inorganic Chemistry. 45 (8). doi:10.1021/ic052110i.

- ^ Zr(0) occur in (η6-(1,3,5-tBu)3C6H3)2Zr and [(η5-C5R5Zr(CO)4]−, see Chirik, P. J.; Bradley, C. A. (2007). "4.06 - Complexes of Zirconium and Hafnium in Oxidation States 0 to ii". Comprehensive Organometallic Chemistry III. From Fundamentals to Applications. Vol. 4. Elsevier Ltd. pp. 697–739. doi:10.1016/B0-08-045047-4/00062-5. ISBN 9780080450476.

- ^ a b Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ a b Calderazzo, Fausto; Pampaloni, Guido (January 1992). "Organometallics of groups 4 and 5: Oxidation states II and lower". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 423 (3): 307–328. doi:10.1016/0022-328X(92)83126-3.

- ^ a b Ma, Wen; Herbert, F. William; Senanayake, Sanjaya D.; Yildiz, Bilge (2015-03-09). "Non-equilibrium oxidation states of zirconium during early stages of metal oxidation". Applied Physics Letters. 106 (10). Bibcode:2015ApPhL.106j1603M. doi:10.1063/1.4914180. hdl:1721.1/104888. ISSN 0003-6951.

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). "Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds". CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (PDF) (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ a b c d e Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3): 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae.

- ^ a b Harper, Douglas. "zircon". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ a b c d Emsley, John (2001). Nature's Building Blocks. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 506–510. ISBN 978-0-19-850341-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lide, David R., ed. (2007–2008). "Zirconium". CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Vol. 4. New York: CRC Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8493-0488-0.

- ^ Considine, Glenn D., ed. (2005). "Zirconium". Van Nostrand's Encyclopedia of Chemistry. New York: Wylie-Interscience. pp. 1778–1779. ISBN 978-0-471-61525-5.

- ^ Winter, Mark (2007). "Electronegativity (Pauling)". University of Sheffield. Retrieved 2024-07-27.

- ^ Schnell I & Albers RC (January 2006). "Zirconium under pressure: phase transitions and thermodynamics". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 18 (5): 16. Bibcode:2006JPCM...18.1483S. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/18/5/001. S2CID 56557217.

- ^ Sumikama, T.; et al. (2021). "Observation of new neutron-rich isotopes in the vicinity of Zr110". Physical Review C. 103 (1): 014614. Bibcode:2021PhRvC.103a4614S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.103.014614. hdl:10261/260248. S2CID 234019083.

- ^ a b Peterson, John; MacDonell, Margaret (2007). "Zirconium". Radiological and Chemical Fact Sheets to Support Health Risk Analyses for Contaminated Areas (PDF). Argonne National Laboratory. pp. 64–65. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-28. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ^ a b c d "Zirconium". How Products Are Made. Advameg Inc. 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-26.

- ^ "Zirconium and Hafnium – Mineral resources" (PDF). 2014.

- ^ a b "Zirconium and Hafnium" (PDF). Mineral Commodity Summaries: 192–193. January 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ^ Ralph, Jolyon & Ralph, Ida (2008). "Minerals that include Zr". Mindat.org. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ Peckett, A.; Phillips, R.; Brown, G. M. (March 1972). "New Zirconium-rich Minerals from Apollo 14 and 15 Lunar Rocks". Nature. 236 (5344): 215–217. Bibcode:1972Natur.236..215P. doi:10.1038/236215a0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Abraham, M. M.; Boatner, L. A.; Ramey, J. O.; Rappaz, M. (1984-12-20). "The occurrence and stability of trivalent zirconium in orthophosphate single crystals". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 81 (12): 5362–5366. Bibcode:1984JChPh..81.5362A. doi:10.1063/1.447678. ISSN 0021-9606.

- ^ Callaghan, R. (2008-02-21). "Zirconium and Hafnium Statistics and Information". US Geological Survey. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ^ Siddiqui, A. S.; Mohapatra, A. K.; Rao, J. V. (2000). "Separation of beach sand minerals" (PDF). Processing of Fines. 2. India: 114–126. ISBN 81-87053-53-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Nielsen, Ralph (2005) "Zirconium and Zirconium Compounds" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a28_543

- ^ a b c d Stwertka, Albert (1996). A Guide to the Elements. Oxford University Press. pp. 117–119. ISBN 978-0-19-508083-4.

- ^ Wu, Ming; Xu, Fei; Dong, Panfei; Wu, Hongzhen; Zhao, Zhiying; Wu, Chenjie; Chi, Ruan; Xu, Zhigao (January 2022). "Process for synergistic extraction of Hf(IV) over Zr(IV) from thiocyanic acid solution with TOPO and N1923". Chemical Engineering and Processing - Process Intensification. 170: 108673. Bibcode:2022CEPPI.17008673W. doi:10.1016/j.cep.2021.108673.

- ^ a b Xiong, Jing; Li, Yang; Zhang, Xiaomeng; Wang, Yong; Zhang, Yanlin; Qi, Tao (2024-03-25). "The Extraction Mechanism of Zirconium and Hafnium in the MIBK-HSCN System". Separations. 11 (4): 93. doi:10.3390/separations11040093. ISSN 2297-8739.

- ^ Pandey, Garima; Darekar, Mayur; Singh, K.K.; Mukhopadhyay, S. (2023-11-02). "Selective extraction of zirconium from zirconium nitrate solution in a pulsed stirred column". Separation Science and Technology. 58 (15–16): 2710–2717. doi:10.1080/01496395.2023.2232102. ISSN 0149-6395.

- ^ Xu, L.; Xiao, Y.; van Sandwijk, A.; Xu, Q.; Yang, Y. (2016). "Separation of Zirconium and Hafnium: A Review". Energy Materials 2014. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 451–457. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-48765-6_53. ISBN 978-3-319-48765-6.

- ^ Shamsuddin, Mohammad (22 June 2021). Physical Chemistry of Metallurgical Processes. The Minerals, Metals & Materials Series (2nd ed.). Springer Cham. pp. 1–5, 390–391. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58069-8. ISBN 978-3-030-58069-8.

- ^ Brady, George Stuart; Clauser, Henry R. & Vaccari, John A. (2002). Materials handbook: an encyclopedia for managers, technical professionals, purchasing and production managers, technicians, and supervisors. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 1063–. ISBN 978-0-07-136076-0. Retrieved 2011-03-18.

- ^ Zardiackas, Lyle D.; Kraay, Matthew J. & Freese, Howard L. (2006). Titanium, niobium, zirconium and tantalum for medical and surgical applications. ASTM International. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-0-8031-3497-3. Retrieved 2011-03-18.

- ^ a b Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ a b "Zirconia". AZoM.com. 2008. Archived from the original on 2009-01-26. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ^ Gauthier, V.; Dettenwanger, F.; Schütze, M. (2002-04-10). "Oxidation behavior of γ-TiAl coated with zirconia thermal barriers". Intermetallics. 10 (7): 667–674. doi:10.1016/S0966-9795(02)00036-5.

- ^ Keenan, P. C. (1954). "Classification of the S-Type Stars". Astrophysical Journal. 120: 484–505. Bibcode:1954ApJ...120..484K. doi:10.1086/145937.

- ^ Opeka, Mark M.; Talmy, Inna G.; Wuchina, Eric J.; Zaykoski, James A.; Causey, Samuel J. (October 1999). "Mechanical, Thermal, and Oxidation Properties of Refractory Hafnium and zirconium Compounds". Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 19 (13–14): 2405–2414. doi:10.1016/S0955-2219(99)00129-6.

- ^ Puls, Manfred P. (2012). The Effect of Hydrogen and Hydrides on the Integrity of Zirconium Alloy Components. Engineering Materials. Springer London. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-4195-2. ISBN 978-1-4471-4194-5.

- ^ Rouquette, J.; Haines, J.; Bornand, V.; Pintard, M.; Papet, Ph.; Bousquet, C.; Konczewicz, L.; Gorelli, F. A.; Hull, S. (2004-07-23). "Pressure tuning of the morphotropic phase boundary in piezoelectric lead zirconate titanate". Physical Review B. 70 (1): 014108. Bibcode:2004PhRvB..70a4108R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.70.014108. ISSN 1098-0121.

- ^ a b South Ural State University, Chelyabinsk, Russian Federation; Sharutin, V.; Tarasova, N. (2023). "Zirconium halide complexes. Synthesis, structure, practical application potential". Bulletin of the South Ural State University Series "Chemistry" (in Russian). 15 (1): 17–30. doi:10.14529/chem230102.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Housecroft, C. E.; Sharpe, A. G. (2018). Inorganic Chemistry (5th ed.). Prentice-Hall. p. 812. ISBN 978-0273742753.

- ^ MSDS sheet for Duratec 400, DuBois Chemicals, Inc.

- ^ Wilkinson, G.; Birmingham, J. M. (1954). "Bis-cyclopentadienyl Compounds of Ti, Zr, V, Nb and Ta". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 76 (17): 4281–4284. doi:10.1021/ja01646a008.; Rouhi, A. Maureen (2004-04-19). "Organozirconium Chemistry Arrives". Chemical & Engineering News. 82 (16): 36–39. doi:10.1021/cen-v082n016.p036. ISSN 0009-2347. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ^ Wailes, P. C. & Weigold, H. (1970). "Hydrido complexes of zirconium I. Preparation". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 24 (2): 405–411. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)80281-8.

- ^ Hart, D. W. & Schwartz, J. (1974). "Hydrozirconation. Organic Synthesis via Organozirconium Intermediates. Synthesis and Rearrangement of Alkylzirconium(IV) Complexes and Their Reaction with Electrophiles". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 96 (26): 8115–8116. doi:10.1021/ja00833a048.

- ^ a b Krebs, Robert E. (1998). The History and Use of our Earth's Chemical Elements. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 98–100. ISBN 978-0-313-30123-0.

- ^ Hedrick, James B. (1998). "Zirconium". Metal Prices in the United States through 1998 (PDF). US Geological Survey. pp. 175–178. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ^ "Fine ceramics – zirconia". Kyocera Inc.

- ^

- Davis, Donald W.; Williams, Ian S.; Krogh, Thomas E. (2003). Hanchar, J.M.; Hoskin, P.W.O. (eds.). "Historical development of U-Pb geochronology" (PDF). Zircon: Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 53: 145–181. doi:10.2113/0530145.

- Kosler, J.; Sylvester, P.J. (2003). Hanchar, J.M.; Hoskin, P.W.O. (eds.). "Present trends and the future of zircon in U-Pb geochronology: laser ablation ICPMS". Zircon: Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 53 (1): 243–275. Bibcode:2003RvMG...53..243K. doi:10.2113/0530243.

- Fedo, C. M.; Sircombe, K. N.; Rainbird, R. H. (2003). "Detrital zircon analysis of the sedimentary record". Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 53 (1): 277–303. Bibcode:2003RvMG...53..277F. doi:10.2113/0530277.

- ^ Rogers, Alfred (1946). "Use of Zirconium in the Vacuum Tube". Transactions of the Electrochemical Society. 88: 207. doi:10.1149/1.3071684.

- ^ "Zirconium Metal: The Magic Industrial Vitamin". Advanced Refractory Metals. Retrieved Oct 21, 2024.

- ^ Ferrando, W.A. (1988). "Processing and use of zirconium based materials". Advanced Materials and Manufacturing Processes. 3 (2): 195–231. doi:10.1080/10426918808953203.

- ^ Kosanke, Kenneth L.; Kosanke, Bonnie J. (1999), "Pyrotechnic Spark Generation", Journal of Pyrotechnics: 49–62, ISBN 978-1-889526-12-6

- ^ Motta, Arthur T.; Capolungo, Laurent; Chen, Long-Qing; Cinbiz, Mahmut Nedim; Daymond, Mark R.; Koss, Donald A.; Lacroix, Evrard; Pastore, Giovanni; Simon, Pierre-Clément A.; Tonks, Michael R.; Wirth, Brian D.; Zikry, Mohammed A. (May 2019). "Hydrogen in zirconium alloys: A review". Journal of Nuclear Materials. 518: 440–460. Bibcode:2019JNuM..518..440M. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2019.02.042.

- ^ Gillon, Luc (1979). Le nucléaire en question, Gembloux Duculot, French edition.

- ^ The Fukushima Daiichi accident. STI/PUB. Vienna, Austria: International Atomic Energy Agency. 2015. pp. 37–42. ISBN 978-92-0-107015-9.

- ^

- Tsuchiya, B.; Huang, J.; Konashi, K.; Teshigawara, M.; Yamawaki, M. (March 2001). "Thermophysical properties of zirconium hydride and uranium–zirconium hydride". Journal of Nuclear Materials. 289 (3): 329–333. Bibcode:2001JNuM..289..329T. doi:10.1016/S0022-3115(01)00420-2.

- Olander, D.; Greenspan, Ehud; Garkisch, Hans D.; Petrovic, Bojan (August 2009). "Uranium–zirconium hydride fuel properties". Nuclear Engineering and Design. 239 (8): 1406–1424. Bibcode:2009NuEnD.239.1406O. doi:10.1016/j.nucengdes.2009.04.001.

- ^

- Meier, S. M.; Gupta, D. K. (1994). "The Evolution of Thermal Barrier Coatings in Gas Turbine Engine Applications". Journal of Engineering for Gas Turbines and Power. 116: 250–257. doi:10.1115/1.2906801. S2CID 53414132.

- Allison, S. W. "37th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit" (PDF). AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference.

- ^ a b Clark, Stephen (2023-11-01). "After decades of dreams, a commercial spaceplane is almost ready to fly". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2023-11-03.

- ^ ATI Materials. "Zircadyne® 702/705 in Hydrogen Peroxide" (PDF). atimaterials. Retrieved 2023-11-03.

- ^ a b c d e Lee DBN, Roberts M, Bluchel CG, Odell RA. (2010) Zirconium: Biomedical and nephrological applications. ASAIO J 56(6):550–556.

- ^ Ash SR. Sorbents in treatment of uremia: A short history and a great future. 2009 Semin Dial 22: 615–622

- ^ Kooman, Jeroen Peter (2024-03-20). "The Revival of Sorbents in Chronic Dialysis Treatment". Seminars in Dialysis. doi:10.1111/sdi.13203. ISSN 0894-0959. PMID 38506130.

- ^ Ingelfinger, Julie R. (2015). "A New Era for the Treatment of Hyperkalemia?". New England Journal of Medicine. 372 (3): 275–7. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1414112. PMID 25415806.

- ^ Laden, Karl (January 4, 1999). Antiperspirants and Deodorants. CRC Press. pp. 137–144. ISBN 978-1-4822-2405-4.

- ^ a b Schroeder, Henry A.; Balassa, Joseph J. (May 1966). "Abnormal trace metals in man: zirconium". Journal of Chronic Diseases. 19 (5): 573–586. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(66)90095-6. PMID 5338082.

- ^ "Zirconium". International Chemical Safety Cards. International Labour Organization. October 2004. Archived from the original on 2008-12-01. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- ^ Zirconium and its compounds 1999. The MAK Collection for Occupational Health and Safety. 224–236

- ^ "NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards – Zirconium compounds (as Zr)". CDC. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ^ PubChem. "Zirconium, Elemental". Hazardous Substances Data Bank. Retrieved 2024-10-25.

- ^ Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft; Commission for the Investigation of Health Hazards of Chemical Compounds in the Work Area, eds. (November 2002). The MAK-Collection for Occupational Health and Safety: Annual Thresholds and Classifications for the Workplace (in German) (1 ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/3527600418.mb744067vere0012. ISBN 978-3-527-60041-0.

- ^ "ANL Human Health Fact Sheet: Zirconium (October 2001)" (PDF). Argonne National Laboratory. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

External links

edit- Chemistry in its element podcast (MP3) from the Royal Society of Chemistry's Chemistry World: Zirconium

- Zirconium at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)