The Cuche Formation (Spanish: Formación Cuche, Cc) is a geological formation of the Floresta Massif, Altiplano Cundiboyacense in the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes. The sequence of siltstones, shales, and sandstone beds dates to the Late Devonian and Early Carboniferous periods, and has a maximum thickness of 900 metres (3,000 ft).

| Cuche Formation | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: Frasnian-Early Carboniferous ~ | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | Floresta Massif |

| Underlies | Girón Fm., Tibasosa Fm. |

| Overlies | Floresta Formation |

| Area | ~36 km2 (14 sq mi) |

| Thickness | 300–900 m (980–2,950 ft) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Sandstone, siltstone |

| Other | Shale |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 5°51′37.2″N 72°56′57.6″W / 5.860333°N 72.949333°W |

| Region | Altiplano Cundiboyacense Eastern Ranges, Andes |

| Country | |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Vereda Cuche |

| Named by | Botero |

| Location | Floresta |

| Year defined | 1950 |

| Coordinates | 5°51′37.2″N 72°56′57.6″W / 5.860333°N 72.949333°W |

| Approximate paleocoordinates | 51°42′S 48°06′W / 51.7°S 48.1°W |

| Region | Boyacá |

| Country | |

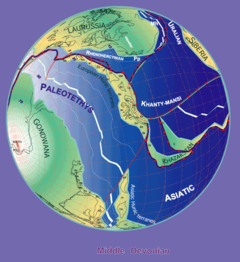

Paleogeography of the Middle Devonian 380 Ma, by Stampfli & Borel | |

The formation was deposited in a tidal-dominated deltaic environment at high southern paleolatitudes at the edge of the Paleozoic Paleo-Tethys Ocean. The Cuche Formation is highly fossiliferous; many Placoderm fish fossils, flora, bivalves, arthropods, crustaceans and ostracods have been discovered in the youngest Paleozoic strate of the Floresta Massif, while the underlying Floresta Formation is richer in trilobite biodiversity.[1]

Etymology

editThe formation was first described as part of the Floresta Series by Olsson and Carter in 1939. The current definition was given by Botero in 1950.[2] The formation is named after the vereda Cuche of Floresta, Boyacá, where the formation outcrops.[3] The word Cuche is taken from Muysccubun, the language of the indigenous Muisca, who inhabited the Altiplano Cundiboyacense before the Spanish conquest.[4]

Regional setting

editThe Floresta Massif is a block in the northern part of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, marked by a metamorphic crystalline core overlain by Devonian to Carboniferous sedimentary sequences; from old to young, the El Tíbet, Floresta and Cuche Formations. The Paleozoic succession is overlain by sediments of much younger date; the Late Jurassic Girón and Early Cretaceous Tibasosa Formations. The massif is bound to the east by the Soapaga Fault and to the west by the Boyacá Fault.[5]

At time of deposition of the Devonian formations, present-day northern South America was located at the edge of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean on the southern hemisphere. The Paleozoic occurrence on the Altiplano is localized in outcrop; the majority of surface sediments are Cretaceous to Paleogene in age. Neogene uplift of the Eastern Ranges, with its main phase in the Plio-Pleistocene, caused the exhumation of older units at surface along major thrust faults in the Eastern Andes. In two phases during the Paleozoic, intrusions occurred into the sedimentary sequence, causing local metamorphism. The first phase is considered pre-Devonian and the latter phase post-Devonian. The remaining stratigraphy of the Cuche Formation appears little affected by this intrusive phase,[6] although slight metamorphism has been identified in later research.[7]

Description

editLithologies

editThe Cuche Formation is characterised by mostly cream and purple coloured shales, with a basal unit of micaceous siltstones with intercalated yellowish-grey shales and 30 metres (98 ft) thick quartzitic and feldspar-rich sandstone beds that colour red caused by meteoric waters. The sandstones have an iron-rich cementation.[3] A middle unit of fine-grained sandstones with thin banks of siltstones follows the lower part and an upper sequence of shales with interbedded ferruginous red beds.[2] The lower sequence contains runzelmark syn-sedimentary structures.[3]

Stratigraphy and depositional environment

editThe Cuche Formation in some places discordantly and in other areas transitionally defined by colour changes,[8][9] overlies the Floresta Formation in Boyacá and the Mogotes Formation in Santander,[10] and is, by an angular unconformity up to 60 degrees,[11] overlain by the Upper Jurassic Girón,[12] and Early Cretaceous Tibasosa Formations.[3] The angular unconformity between the Paleozoic and Mesozoic is exposed along the road between Duitama and Sogamoso, and is the location where the first flora fossils were found in 1978.[11]

The age of the Cuche Formation has been estimated to be Late Devonian to Early Carboniferous,[2][13] after an original designation as Permian-Carboniferous by Botero in 1950, further restricted to the Carboniferous by Julivert in 1968.[14] The formation covers an area of approximately 36 square kilometres (14 sq mi) and ranges in thickness between 300 and 900 metres (980 and 2,950 ft).[2] Stratigraphically, the Cuche Formation is time equivalent with the Diamante Formation of the Santander Massif to the north of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense.[15] To the west of Paz de Río, the Cuche Formation is thrusted upon the Neogene Concentración Formation by the Soapaga Fault.[16] In the northern part of the Floresta Massif, the contact between the metamorphic Otengá Stock and the Cuche Formation is formed by the Duga Fault.[17]

Based on the preservation of fossils, the lithologies, syn-sedimentary structures and stratigraphic position, a depositional environment of shallow low energy waters has been proposed, possibly in a lagoonal setting at the edge of a regressional Paleo-Tethys Ocean.[1][18] Other parts of the Cuche Formation were deposited in a continental environment, evidenced by the red beds and absence of marine fossils and abundant root imprints.[19] Overall, the sequence represents a coastal deltaic environment with frequent marine incursions, a tidal deltaic setting.[20][21]

Fossil content

editThe first identification of fossil content of the Cuche Formation was done by Botero, who studied the formation in 1950. Research in the early 1980s revealed the presence of many more fossils in the formation and among the first fossil flora found were species then identified as the genera Ginkgo and Baiera.[14] The lower units show poorly preserved plant remains and the overlying shales provided arthropods and crustaceans. In the middle units of the formation, more and better preserved plant fossils were found alongside bivalves, ostracods (of the genus Welleria) and arthropods.[22]

The Cuche Formation contains unique Placoderm fish fossils, first noted by Mojica and Villarroel in 1984.[23] Across the section, also plant fossils and bivalves are found. In this part of the sequence the first fish fossils were discovered. The top section provided brachiopods (genus Lingula) and other at that moment undetermined fossil fragments.[24]

Later research has provided more insight into the flora of the formation, with the "Ginkgo" species possibly a Ginkgophyton sp..[25] Additionally, fossil flora of Colpodexylon cf. deatsii and cf. Archaeopteris sp. have been described from the formation.[26] In the continental sandstone facies of the Cuche Formation, ichnofossils of Diplichnites have been described.[27]

Fishes

editA closer paleogeographical relation between the paleocontinents has been suggested to explain this curious combination.

Remains of the cartilaginous fish Antarctilamna sp., the Placoderms Asterolepis sp. and two species of Bothriolepis,[28] the spiny shark ?Cheiracanthoides sp., the Porolepiform Holoptychius sp., and the Rhizodontid ?Strepsodus sp. have been uncovered from the Cuche Formation.[23] Several other fossils are less well recognizable at the genus level, among others Actinopterygii, Sarcopterygii,[29] and Osteolepiformes.[30] The fish specimens were found in sediments possibly representing localized transgressive marine incursions into brackish lagoonal settings,[20][31] in all cases associated with the presence of bivalves, ostracods and brachiopods.[32]

The fossil fish assemblage of the Cuche Formation presents a curious mixture of Euramerican "Old Red Sandstone" (Catskills, Greenland, Scotland and the Baltic states)[20] species (Asterolepis and Holoptychius), and Gondwanan taxa (Antarctilamna), suggesting the interchange of species between the paleogeographical regions, possibly at closer distance than is presented in most paleogeographical models.[33][34] This hypothesis is further strengthened by the discovery of typical Euramerican flora, as Archaeopteris.[26]

Asterolepis has been known only from Euramerican fossils, except for a specimen found in Iran.[20] The fish of the Cuche Formation are quite different from Bolivian Devonian fossils, with the exception of Antarctilamna. The similar sediments of the Colpacucho Formation in Bolivia have not provided the species discovered in the Cuche Formation, probably because of the cooler climate of the Devonian Bolivian seas more to the south than the paleogeographical position of northern Colombia (already around 51°S) at that time.[34]

Fossils assigned to Florestacanthus cf. morenoi, Colombiaspis rinconensis and Colombialepis villarroeli were later described from the Cuche Formation.[35][36][37]

Eurypterids

editIn 2019, fragments of the eurypterid Pterygotus were retrieved from the formation. The find represents the first sea scorpion from Colombia and the fourth from South America.[38] The specimen (SGC-MGJRG.2018.I.5), assigned with uncertainty to P. bolivianus due to similarities with its holotype, represents the first eurypterid of Colombia and the fourth of South America. The fossil was dated as Frasnian (Late Devonian), showing that Pterygotus did not become extinct during the Middle Devonian as previously thought.[39]

Outcrops

editThe Cuche Formation is found at the Floresta Massif around its type locality in Floresta, Boyacá, stretching across Floresta to the west close to Belén and Paz de Río,[2][40] up to north of Tibasosa in the valley of the Chicamocha River.[41]

Regional correlations

edit- Legend

- group

- important formation

- fossiliferous formation

- minor formation

- (age in Ma)

- proximal Llanos (Medina)[note 1]

- distal Llanos (Saltarin 1A well)[note 2]

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Morzadec et al., 2015, p.331

- ^ a b c d e Rodríguez & Solano, 2000, p.57

- ^ a b c d Mojica & Villarroel, 1984, p.65

- ^ Giraldo Gallego, 2014

- ^ Mojica & Villarroel, 1984, p.60

- ^ Mojica & Villarroel, 1984, p.63

- ^ Geoestudios, 2006, p.68

- ^ Rodríguez & Solano, 2000, p.58

- ^ Mojica & Villarroel, 1984, p.67

- ^ Rodríguez Gutiérrez, 2017, p.75

- ^ a b Mojica & Villarroel, 1984, p.68

- ^ Rodríguez & Solano, 2000, p.41

- ^ Villarroel & Mojica, 1985, p.85

- ^ a b Mojica & Villarroel, 1984, p.71

- ^ Villafañez Cardona, 2012, p.39

- ^ Geoestudios, 2006, p.14

- ^ Geoestudios, 2006, p.202

- ^ Mojica & Villarroel, 1984, p.75

- ^ Giroud López, 2014, p.146

- ^ a b c d Janvier & Villarroel, 2000, p.756

- ^ Giroud López, 2014, p.147

- ^ Mojica & Villarroel, 1984, p.72

- ^ a b Janvier & Villarroel, 2000, p.729

- ^ Mojica & Villarroel, 1984, p.66

- ^ Mojica & Villarroel, 1984, p.74

- ^ a b Berry et al., 2000

- ^ Gómez Cruz et al., 2015

- ^ Janvier & Villarroel, 1998, p.7

- ^ Janvier & Villarroel, 1998, p.11

- ^ Janvier & Villarroel, 1998, p.12

- ^ Janvier & Villarroel, 1998, p.9

- ^ Janvier & Villarroel, 1998, p.14

- ^ Janvier & Villarroel, 1998, p.15

- ^ a b Janvier & Villarroel, 2000, p.757

- ^ Olive et al., 2019, p.4

- ^ Olive et al., 2019, p.6

- ^ Olive et al., 2019, p.8

- ^ Olive et al., 2019, p.17

- ^ Olive et al., 2019, p.13

- ^ Plancha 172, 1998

- ^ Pardo Díaz et al., 2014, p.55

- ^ a b c d e f García González et al., 2009, p.27

- ^ a b c d e f García González et al., 2009, p.50

- ^ a b García González et al., 2009, p.85

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Barrero et al., 2007, p.60

- ^ a b c d e f g h Barrero et al., 2007, p.58

- ^ Plancha 111, 2001, p.29

- ^ a b Plancha 177, 2015, p.39

- ^ a b Plancha 111, 2001, p.26

- ^ Plancha 111, 2001, p.24

- ^ Plancha 111, 2001, p.23

- ^ a b Pulido & Gómez, 2001, p.32

- ^ Pulido & Gómez, 2001, p.30

- ^ a b Pulido & Gómez, 2001, pp.21-26

- ^ Pulido & Gómez, 2001, p.28

- ^ Correa Martínez et al., 2019, p.49

- ^ Plancha 303, 2002, p.27

- ^ Terraza et al., 2008, p.22

- ^ Plancha 229, 2015, pp.46-55

- ^ Plancha 303, 2002, p.26

- ^ Moreno Sánchez et al., 2009, p.53

- ^ Mantilla Figueroa et al., 2015, p.43

- ^ Manosalva Sánchez et al., 2017, p.84

- ^ a b Plancha 303, 2002, p.24

- ^ a b Mantilla Figueroa et al., 2015, p.42

- ^ Arango Mejía et al., 2012, p.25

- ^ Plancha 350, 2011, p.49

- ^ Pulido & Gómez, 2001, pp.17-21

- ^ Plancha 111, 2001, p.13

- ^ Plancha 303, 2002, p.23

- ^ Plancha 348, 2015, p.38

- ^ Planchas 367-414, 2003, p.35

- ^ Toro Toro et al., 2014, p.22

- ^ Plancha 303, 2002, p.21

- ^ a b c d Bonilla et al., 2016, p.19

- ^ Gómez Tapias et al., 2015, p.209

- ^ a b Bonilla et al., 2016, p.22

- ^ a b Duarte et al., 2019

- ^ García González et al., 2009

- ^ Pulido & Gómez, 2001

- ^ García González et al., 2009, p.60

Bibliography

editGeology

edit- Geoestudios; ANH (2006), Cartografía geológica cuenca Cordillera Oriental - Sector Soapaga (PDF), ANH, pp. 1–239, retrieved 2017-05-05

- Giraldo Gallego, Diana Andrea (2014), "Antropónimos muiscas en la Colonia (1608-1650)", Forma y Función, 27 (2): 41–94, doi:10.15446/fyf.v27n2.47666, retrieved 2017-05-05

- Mojica, Jairo; Villarroel, Carlos (1984), "Contribución al conocimiento de las unidades paleozoicas del área de Floresta (Cordillera Oriental Colombiana; Departamento de Boyacá) y en especial al de la Formación Cuche" (PDF), Geología Colombiana, 13: 55–80, retrieved 2017-05-05

- Pardo Díaz, Marta Yolima; Gil Padilla, Marta Liliana; Garavito Rincón, Laura Natalia; Corredor Vargas, Pedro; Gutiérrez Barrios, Carolina; Parra, Wilson; Amaya Pedraza, Nancy (2014), Estudios técnicos, económicos, sociales y ambientales Complejo de Páramos Altiplano Cundiboyacense, Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt & CORPOBOYACÁ, pp. 1–546

- Rodríguez Gutiérrez, Madeleidy (2017), Criterios de Análisis y Validación del Comportamiento de los Túneles con Squeezing en Rocas, Escuela Colombiana de Ingeniería Julio Garavito, pp. 1–541

- Rodríguez Parra, Antonio José; Solano Silva, Orlando (2000), Mapa Geológico del Departamento de Boyacá - 1:250,000 - Memoria explicativa, INGEOMINAS, pp. 1–120

- Villafañez Cardona, Yohana (2012), Análisis de procedencia de areniscas cuarzosas del Devónico-Carbonífero de la Formación Floresta (Norte de Santander): Consideraciones paleogeográficas regionales, EAFIT, pp. 1–89

Paleontology

edit- Olive, Sébastien; Pradel, Alan; Martinez Pérez, Carlos; Janvier, Philippe; Lamsdell, James C.; Gueriau, Pierre; Rabet, Nicolas; Duranleau-Gagnon, Philippe; Cardenas Rozo, Andres L.; Zapata Ramirez, Paula A.; Botella, Héctor (2019), "New insights into Late Devonian vertebrates and associated fauna from the Cuche Formation (Floresta Massif, Colombia)", Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, e1620247 (3): 1–18, Bibcode:2019JVPal..39E0247O, doi:10.1080/02724634.2019.1620247, hdl:10784/26939, retrieved 2019-10-09 doi:10.1080/02724634.2019.1620247

- Gómez Cruz, Arley de Jesús; Moreno Sánchez, Mario; Lemus Restrepo, Alexander (2015), Diplicnites isp. del Devónico y Carbonífero de Colombia, Tercer Simposio Latinoamericano de Icnología, Colonia de Sacramento, Uruguay, pp. _, retrieved 2017-05-05

- Morzadec, Pierre; Mergl, Michal; Villarroel, Carlos; Janvier, Philippe; Racheboeuf, Patrick R. (2015), "Trilobites and inarticulate brachiopods from the Devonian Floresta Formation of Colombia: a review" (PDF), Bulletin of Geosciences, 90: 331–358, doi:10.3140/bull.geosci.1515, retrieved 2017-05-05

- Giroud López, Marie Joëlle (2014), El Mar en la Localidad Tipo del Devónico Medio, del Municipio de Floresta - Boyacá, Colombia, Universidad de La Habana, pp. 1–174, retrieved 2017-05-05

- Berry, Christopher M.; Morel, Eduardo; Mojica, Jairo; Villarroel, Carlos (2000), "Devonian plants from Colombia, with discussion of their geological and palaeogeographical context", Geological Magazine, 137 (3): 257–268, Bibcode:2000GeoM..137..257B, doi:10.1017/S0016756800003964, retrieved 2017-05-05

- Janvier, Philippe; Villarroel, Carlos (2000), "Devonian vertebrates from Colombia", Palaeontology, 43 (4): 729–763, Bibcode:2000Palgy..43..729J, doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00147, retrieved 2017-05-05

- Janvier, Philippe; Villarroel, Carlos (1998), "Los Peces Devónicos del Macizo de Floresta (Boyacá, Colombia). Consideraciones taxonómicas, bioestratigráficas, biogeográficas y ambientales", Geología Colombiana, 23: 3–18, retrieved 2017-05-05

Maps

edit- Renzoni, Giancarlo; Rosas, Humberto (2009), Plancha 171 - Duitama - 1:100,000, INGEOMINAS, p. 1, retrieved 2017-06-06

- Ulloa, Carlos E.; Guerra, Álvaro; Escovar, Ricardo (1998), Plancha 172 - Paz de Río - 1:100,000, INGEOMINAS, p. 1, retrieved 2017-06-06

- Renzoni, Giancarlo; Rosas, Humberto; Etayo Serna, Fernando (1998), Plancha 191 - Tunja - 1:100,000, INGEOMINAS, p. 1, retrieved 2017-06-06