Quiz Show is a 1994 American historical mystery-drama film[3][4] directed and produced by Robert Redford. Dramatizing the Twenty-One quiz show scandals of the 1950s, the screenplay by Paul Attanasio[5] adapts the memoirs of Richard N. Goodwin, a U.S. Congressional lawyer who investigated the accusations of game-fixing by show producers.[6] The film chronicles the rise and fall of popular contestant Charles Van Doren after the fixed loss of Herb Stempel and Goodwin's subsequent probe.

| Quiz Show | |

|---|---|

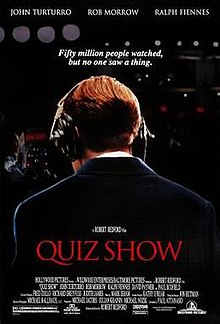

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Robert Redford |

| Screenplay by | Paul Attanasio |

| Based on | Remembering America by Richard Goodwin |

| Produced by | Robert Redford Michael Jacobs Julian Krainin Michael Nozik |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Michael Ballhaus |

| Edited by | Stu Linder |

| Music by | Mark Isham |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Pictures Distribution |

Release date |

|

Running time | 133 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $31 million[2] |

| Box office | $52.2 million |

The film stars John Turturro as Stempel, Rob Morrow as Goodwin, and Ralph Fiennes as Charles Van Doren. Paul Scofield, David Paymer, Hank Azaria, Martin Scorsese, Mira Sorvino, and Christopher McDonald play supporting roles.[5][7][8] The real Goodwin and Stempel served as technical advisors to the production.

The film received generally positive reviews and was nominated for several awards, including a Best Picture Oscar nomination and several Golden Globe Awards, but was a financial disappointment, grossing $52.2 million against a $31 million budget.

Plot

editIn 1958, the questions and answers to be used for the latest broadcast of NBC's popular quiz show Twenty-One are transported from a secure bank vault to the studio. The evening's main attraction is Queens resident Herb Stempel, the reigning champion, who correctly answers every single question he is asked. Eventually, both the network and the program's corporate sponsor, the supplementary tonic Geritol, begin to fear that Stempel's approval ratings are beginning to level out, and decide that the show would benefit from new talent.

Producers Dan Enright and Albert Freedman are surprised when Columbia University instructor Charles Van Doren, son of a prominent literary family, visits their office to audition for a different, less difficult show by the same producers, Tic-Tac-Dough. Realizing that they have found an ideal challenger for Stempel, they offer to ask the same questions during the show which Van Doren correctly answered during his audition. He refuses, but when he nears a game-winning 21 points on the show, he is asked one of the questions from his audition. After a moment of moral indecision, he gives the correct answer. Stempel deliberately misses an easy question and loses, having been promised a future in television if he does so.

In the subsequent weeks, Van Doren's winning streak makes him a national celebrity, but he reluctantly buckles under the pressure and allows Enright and Freedman to start giving him the answers. Meanwhile, Stempel, having lost his prize money to an unscrupulous bookie, begins threatening legal action against NBC after weeks pass without his return to television. He visits New York County District Attorney Frank Hogan, who convenes a grand jury to look into his allegations.

Richard Goodwin, a young Congressional lawyer, learns that the grand jury findings have been sealed and travels to New York City to investigate rumors of rigged quiz shows. Visiting a number of contestants, including Stempel and Van Doren, he begins to suspect that Twenty-One is a fixed operation. Stempel's volatile personality damages his credibility, and nobody else seems willing to confirm that the show is fixed. Fearing Goodwin will give up the investigation, Stempel confesses that he was fed the correct answers during his run on the show, and insists that Van Doren must have been involved as well. Another former contestant gives Goodwin a set of answers that he mailed to himself two days before his quiz show appearance, which Goodwin takes to be corroborating evidence.

A guilt-ridden Van Doren deliberately loses, but NBC offers him a lucrative contract to appear as a special correspondent on the morning Today show. The House Committee for Legislative Oversight convenes a hearing, at which Goodwin presents his evidence of the quiz show's corruption. Stempel testifies at the hearing but fails to convince the committee, and both NBC network head Robert Kintner and Geritol executive Martin Rittenhome deny any knowledge of Twenty-One being rigged. Subpoenaed by Goodwin, Van Doren testifies before the committee and admits his role in the deception. After the hearing adjourns, he learns from reporters that he has been fired from Today and that Columbia's board of trustees will be asking for his resignation.

Goodwin believes that he is close to a victory against Geritol and NBC, but realizes that Enright and Freedman will not jeopardize their own futures in television by turning against their bosses. He silently watches the producers' testimony, vindicating the sponsors and the network from any wrongdoing, and taking full responsibility for rigging the show. Disgusted, he steps outside and sees Van Doren, who waves at him before boarding a taxi.

Cast

edit- John Turturro as Herb Stempel

- Rob Morrow as Richard N. Goodwin

- Ralph Fiennes as Charles Van Doren

- David Paymer as Dan Enright

- Paul Scofield as Mark Van Doren

- Hank Azaria as Albert Freedman

- Christopher McDonald as Jack Barry

- Johann Carlo as Toby Stempel

- Elizabeth Wilson as Dorothy Van Doren

- Allan Rich as Robert E. Kintner

- Mira Sorvino as Sandra Goodwin

- George Martin as Chairman Oren Harris

- Paul Guilfoyle as Robert W. Lishman

- Martin Scorsese as Martin Rittenhome

- Griffin Dunne as Geritol Account Executive

- Ben Shenkman as Childress

- Timothy Busfield as Fred

- Jack Gilpin as Jack

- Bruce Altman as Gene

- Joe Lisi as Reporter

- Neil Ross as Twenty-One Announcer

- Barry Levinson as Dave Garroway

- Jeffrey Nordling as John Van Doren

- Douglas McGrath as James Snodgrass

- Stephen Pearlman as Judge Mitchell Schweitzer

- William Fichtner as NBC Stage Manager

- Illeana Douglas as Helena

- Ethan Hawke and Calista Flockhart as Columbia Students

Historical accuracy

editAlthough much of Quiz Show is generally accurate based on the actual events,[9][10] its use of artistic license generated controversy and criticism (especially in regard to character changes) by critics and real-life figures involved with the scandal.[11]

The artistic licenses included compressing three years of scandal into one,[12] changing the location of Van Doren's first meeting with Goodwin, altering the start time of Goodwin's investigation, and making Van Doren's choice to incorrectly answer a question his own instead of that of NBC.[9]

The fateful episode in which Van Doren defeated Stempel is inaccurately portrayed. In the film, Stempel's intentionally incorrect response about Marty is in response to a three-point question with the score 18-10 in his favor. In reality, the question was worth five points and the score was 16-10. The film also presents this as the deciding moment of the game, with Van Doren correctly answering the next question about the Civil War to win. Van Doren's next question was actually about Pizarro's conquest of the Incas, and Stempel correctly replied to his next question about the voyages of Christopher Columbus. This forced a 21-21 tie and a new game to determine the winner. The incorrect answer that doomed Stempel occurred in the second game in response to a question about newspaperman William Allen White. Both Van Doren and Stempel then correctly answered a question about the wives of King Henry VIII, and the game ended when Van Doren elected to stop, winning by a score of 18-10.[13]

The film's magnification of the role that Twenty-One and its producer Albert Freedman played in the scandal was criticized by Jeff Kisslehoff, who wrote The Box: An Oral History of Television, 1920-1961, as well as Freedman himself. Kisslehoff argued that the dishonest practice originated in the radio era when players were overtly coached.[3] Goodwin's role in the investigation was less important than as portrayed in the film; he only became involved two years after Twenty-One ended syndication, and a collection of information was handled by publications and assistant district attorneys in New York City.[3] Joe Stone, a congressional committee consultant who investigated the scandal for four years, was angered about the screenplay's spotlight on Goodwin and the fact that Goodwin accepted most of the credit for uncovering the scandal when the film was released. Goodwin's wife Doris Kearns Goodwin apologized to Stone about the film.[3]

Other dramatic liberties involved simplifications, such as the character of Van Doren, who is a "shallow icon" devoid of the ambiguities of the actual Van Doren, the Chicago Reader analyzed.[14] In a July 2008 edition of The New Yorker, Van Doren wrote about the events depicted in the film. He agreed with many of the details but wrote that his girlfriend at the time of his Twenty-One appearances was not depicted in the film. He also noted that he continued teaching after the scandal, contradicting the film's epilogue that states that he never returned to academia.[15]

For legal reasons, the name of Matthew Rosenhaus, CEO of the company that owned Geritol, was changed to Martin Rittenhome, and his personality reflected that of Charles Revson, who was the president of cosmetics brand Revlon that had sponsored another quiz show involved in the scandal, The $64,000 Question (1955–1958).[16]

Production

editBackground

editWhen Robert Redford first saw Twenty-One in the late 1950s, he was in his early 20s taking art and acting classes in New York.[17] He recalled when he first saw Van Doren on the show, "Watching him and the other contestants was irresistible. The actor in me looked at the show and felt I was watching other actors. It was too much to believe, but at the same time, I never doubted the show. I hadn't had evidence television could trick us. But the merchant mentality was already taking hold, and as we know now, there's little morality there."[18] Redford described the scandal as "really the first in a series of scandals . . . that have left us numbed, unsure of what or who to believe."[17]

A 1992 documentary on the scandal produced by Julian Krainin as an installment of the PBS series American Experience predated the film.[12]

Writing

editQuiz Show is based on a chapter of the book Remembering America: A Voice from the Sixties (1988) by Richard N. Goodwin,[17] who also was one of the film's many producers.[19] Paul Attanasio began writing the screenplay in 1990, joining immediately for the subject matter's "complex ironies," such as with its main characters.[20] Completing many drafts over the course of three years, Attanasio wrote the script by watching clips of Twenty-One, reading old articles about the scandal, learning about the 1950s television landscape at the Museum of Broadcasting and meeting with Goodwin.[19][21] Redford researched the topic by reading Dan Wakefield's book New York in the Fifties and brought Wakefield to the film set as an advisor who also was given a cameo appearance.[22] Redford had known Goodwin since appearing in The Candidate (1972), and he helped Attanasio integrate Goodwin's personality into the script.[23]

Because the story lacked a protagonist, Attanasio employed "shifting points of view" while maintaining a through line, which complicated the writing of the screenplay.[24] In depicting the themes of ethnic conflict between White Anglo-Saxon Protestants and Jewish characters, Attanasio borrowed from his experiences as a member of an Italian-American family. His relatives were outraged by the stereotypical depiction of Italians as loudmouth gangsters in the media.[19] He also integrated the duplicitous personalities of those with whom he had worked in the film industry in order to incorporate themes of disillusion.[19]

Development

editRedford first read a rough draft after completing production of A River Runs Through It (1992), "looking for something edgier, faster-paced, urban, where I could move the camera more."[17] Barry Levinson's Baltimore Pictures and TriStar Pictures began development of a film project based on the quiz-show scandal, which proved difficult to sell because of its uncommercial style and subject matter. TriStar placed it in turnaround in September 1992, and it was then moved to Walt Disney Studios, which invested $20 million into the budget and launched the project into production through its Hollywood Pictures label in Spring 1993 after Redford agreed to direct.[18] Although Disney offered Charles Van Doren $100,000 to act as a consultant, he declined.[25]

Casting

editCasting took place in New York in May 1993.[26] Redford originally planned for an American actor to play Van Doren, but after auditioning several actors such as William Baldwin,[26] he failed to find the "combination of elements" required for the character and awarded the part to British actor Ralph Fiennes.[17] To prepare for the role, Fiennes viewed clips of Van Doren on Twenty-One and televised interviews with him, and he also visited Van Doren's Cornwall, Connecticut home.[18] Although the men did not meet, Fiennes gained a sense of atmosphere from Van Doren's home.[27] Paul Newman was initially considered for the role of Mark Van Doren, but he declined.[17] In May 1993, Chris O'Donnell was reported to be talking with Redford about appearing in the film, but he was not cast.[28]

Turturro found it easy to assume the Stempel's character, but he gained 25 pounds for the role and altered his voice to mimic Stempel's.[27] After his initial success in Northern Exposure (1990–1995), Rob Morrow was offered several film roles but rejected them until he accepted the offer for Quiz Show: "I knew this was the one. It had the cachet of Bob Redford and was incredibly well-written." In getting the idea of the character of Goodwin, Morrow read four of his books.[29]

Levinson was originally attached to the project as director, but because of his commitment to the film Bugsy (1991), the job went to Redford.[30] However, Levinson was then cast by Redford for the part of Dave Garroway, as Redford liked his "easygoing, casual manner" and interest in 1950s culture.[16] For the scene involving J. Fred Muggs, a chimpanzee "unnerved by the lights and cameras" was found, as no animals trained for film production were available.[16] Martin Scorsese was cast by Redford for his physical features as well as for "his own personal style and delivery, so I found it interesting to have him play a tough character gently. And given his delivery style, in which he talks real fast, I thought it would make the character extremely menacing."[16]

Themes

editQuiz Show has been categorized as a Faustian tale[31] about the loss of innocence (both for its three main characters and the entire country),[19] temptation with money,[32] moral ambiguity,[10] positive guises hiding negative actions,[10] the cult of celebrity,[32] the negative side effects of fame,[32] the power and corruption of big business and mass media,[32][33] the consequences of overcompetitiveness in business,[34] racial, ethnic and class conflict[7][14][35] and the discord between education and entertainment.[32] Attanasio, Redford and many film critics considered Quiz Show's subject matter essential, as it marked the beginning of the country's loss of innocence and faith in its trusted institutions that was exacerbated by events such as the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal.[19][27][31][36][37]

Reviews from TV Guide and Newsweek noted that in the era of the film's release, scandals and culturally unacceptable behaviors were more expected and less shocking to the American public than they had been in the 1950s.[7][38] Newsweek wrote: "Neck high in '90s cynicism, it's hard to believe the tremors these scandals provoked. [...] In the '50s, Ingrid Bergman was blacklisted from Hollywood for having a baby out of wedlock. Today, Oliver North makes hash of the Constitution and it jump-starts his political career. What used to ruin your life gets you invited on 'Oprah' and a fat book deal. Shame is for losers; public confession and a 12-step program can turn you into a role model."[7]

Release

editQuiz Show was released in September 1994. although some reports from late 1993 indicated that the film was planned to be distributed in the first half of 1994.[39]

With Quiz Show, Disney launched a platform-release strategy geared to generate interest in and publicity for the film by releasing it in a limited number of theaters before opening wider. The Shawshank Redemption, released around the same time, was distributed in a similar manner, but as with Quiz Show, it was a box-office failure.[40]

Quiz Show opened in New York on September 14, 1994 and expanded to 27 screens for the weekend, grossing $757,714, the fifth-highest-grossing opening weekend for a film showing on fewer than 50 screens.[1][41] It grossed $792,366 in its first five days.[42] The film gradually expanded over the next four weeks to a maximum of 822 screens and grossed a total of $24,822,619 in the U.S. and Canada.[43] In the U.S., the film's box-office performance began to fall even after its four Academy Award nominations, dropping 63% in weekly grosses for the week of March 12, 1995.[44]

Following its theatrical run, Quiz Show ran at international festivals, such as the 1995 Berlin International Film Festival[45] and the Chinese edition of the Sundance Film Festival, which ran from October 5 to 12, 1995.[46] Five weeks prior to the Berlin festival, Redford informed Disney that he would not attend because of his work in Up Close and Personal (1996) and commitment to the Sundance festival. However, according to festival director Moritz de Hadeln, the festival had agreed to promote Quiz Show only if Redford had attended. His failure to attend eroded his relationship with Disney and other film-festival organizers, and it negatively impacted promotion for the film's international release.[47]

In countries such as Germany and France, Quiz Show generally performed far better in big cities than in smaller towns and attracted more female viewers than male. In Italy, despite much press and interest in the film, it was not a commercial success. The film performed well in Spain, where it grossed $368,000 within six days during a 31-screen run.[48] The film grossed an international total of $1.4 million by February 12, 1995.[49] It finally grossed $27.4 million internationally, for a worldwide total of $52.2 million.[50][51]

Critical reception

editQuiz Show currently holds a 97% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 117 reviews, with an average rating of 8.4/10. The site's consensus states: "Directed with sly refinement by Robert Redford and given pizazz by a slew of superb performances, Quiz Show intelligently interrogates the erosion of public standards without settling on tidy answers."[52]

Film critic Roger Ebert awarded the film three and a half stars out of four, calling the screenplay "smart, subtle and ruthless."[53] Web critic James Berardinelli praised the "superb performances by Fiennes" and wrote that "John Turturro is exceptional as the uncharismatic Herbie Stempel."[54] Writing for Entertainment Weekly, Owen Gleiberman highlighted the supporting performance of Paul Scofield as Mark Van Doren, stating that "it's in the relationship between the two Van Dorens that Quiz Show finds its soul."[55] Kenneth Turan called Scofield's performance his best since A Man for All Seasons (1966) and suggested that the film "would have been a very different experience" without Fiennes' "ability to project the pain behind a well-mannered facade, to turn intellectual and emotional agony into a real and living thing",[10] but also criticized Turturro's and Morrow's exaggerated performances.[10]

Charles Van Doren said: "I understand that movies need to compress and conflate, but what bothered me most was the epilogue stating that I never taught again. I didn't stop teaching, although it was a long time before I taught again in a college. I did enjoy John Turturro's version of Stempel. And I couldn't help but laugh when Stempel referred to me in the film as 'Charles Van Fucking Moron.'"[56]

Year-end lists

edit- 1st – Joan Vadeboncoeur, Syracuse Herald American[57]

- 1st – John Hurley, Staten Island Advance[58]

- 2nd – Peter Travers, Rolling Stone[59]

- 2nd – Sean P. Means, The Salt Lake Tribune[60]

- 2nd – Craig Kopp, The Cincinnati Post[61]

- 2nd – Terry Lawson, Dayton Daily News[62]

- 2nd – Robert Denerstein, Rocky Mountain News[63]

- 2nd – Scott Schuldt, The Oklahoman[64]

- 2nd – National Board of Review[65]

- 3rd – Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times[66]

- 3rd – Janet Maslin, The New York Times[67]

- 3rd – Desson Howe, The Washington Post[68]

- 3rd – Stephen Hunter, The Baltimore Sun[69]

- 3rd – David Stupich, The Milwaukee Journal[70]

- 3rd – Michael Mills, The Palm Beach Post[71]

- 3rd – Sandi Davis, The Oklahoman[72]

- 3rd – Mal Vincent, The Virginian-Pilot[73]

- 4th – Steve Persall, St. Petersburg Times[74]

- 4th – Christopher Sheid, The Munster Times[75]

- 5th – Gene Siskel, Chicago Tribune[76]

- 6th – Michael MacCambridge, Austin American-Statesman[77]

- 7th – Bob Strauss, Los Angeles Daily News[78]

- 7th – Douglas Armstrong, The Milwaukee Journal[79]

- 7th – Jerry Roberts, Daily Breeze[80]

- 8th – David Rahr, The Santa Fe New Mexican[81]

- 9th – Mack Bates, The Milwaukee Journal[82]

- 10th – Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times[83]

- 10th – James Berardinelli, ReelViews[84]

- Top 7 (not ranked) – Duane Dudek, Milwaukee Sentinel[85]

- Top 9 (not ranked) – Dan Webster, The Spokesman-Review[86]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Mike Clark, USA Today[87]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – William Arnold, Seattle Post-Intelligencer[88]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Matt Zoller Seitz, Dallas Observer[89]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Eleanor Ringel, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution[90]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Steve Murray, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution[90]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Jeff Simon, The Buffalo News[91]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Bob Ross, The Tampa Tribune[92]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Eric Harrison, Arkansas Democrat-Gazette[93]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Mike Mayo, The Roanoke Times[94]

- Top 10 (not ranked) – Betsy Pickle, Knoxville News-Sentinel[95]

- Top 10 (not ranked) – Bob Carlton, The Birmingham News[96]

- Top 10 (not ranked) – Jim Delmont and Jim Minge, Omaha World-Herald[97]

- Top 10 (not ranked) – Howie Movshovitz, The Denver Post[98]

- Top 10 (not ranked) – George Meyer, The Ledger[99]

- "Next Best" 10 (not ranked) – Gary Arnold, The Washington Times[100]

- Top 10 Runner-up – Dan Craft, The Pantagraph[101]

- Best of the year (not ranked) - Michael Medved, Sneak Previews[102]

- Honorable mention – Glenn Lovell, San Jose Mercury News[103]

- Honorable mention – Dennis King, Tulsa World[104]

- Honorable mention – David Elliott, The San Diego Union-Tribune[105]

Accolades

edit| Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20/20 Award[106] | Best Picture | Quiz Show | Nominated |

| Best Director | Robert Redford | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Paul Scofield | Nominated | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Paul Attanasio | Nominated | |

| Best Art Direction | Jon Hutman | Nominated | |

| Academy Award[107] | Best Picture | Robert Redford, Michael Jacobs, Julian Kranin and Michael Nozik | Nominated |

| Best Director | Robert Redford | Nominated | |

| Best Actor in a Supporting Role | Paul Scofield | Nominated | |

| Best Screenplay Based on Material Previously Produced or Published | Paul Attanasio | Nominated | |

| Awards Circuit Community Awards[108] | Best Achievement in Directing | Robert Redford | Nominated |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Paul Scofield | Nominated | |

| Boston Society of Film Critics Award[109] | Best Director | Robert Redford | Runner-up |

| British Academy Film Award[110][111] | Best Film | Robert Redford | Nominated |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Paul Attanasio | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Paul Scofield | Nominated | |

| Directors Guild of America Award[112] | Outstanding Directing — Feature Film | Robert Redford | Nominated |

| Golden Globe Award[113] | Best Motion Picture – Drama | Robert Redford | Nominated |

| Best Director | Robert Redford | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | John Turturro | Nominated | |

| Best Screenplay | Paul Attanasio | Nominated | |

| Golden Laurel Award[114] | Outstanding Producer of Theatrical Motion Pictures | Robert Redford, Michael Jacobs, Julien Krainin, Michael Nozik | Nominated |

| National Society of Film Critics[115] | Best Supporting Actor | Paul Scofield | 3rd place |

| Best Screenplay | Paul Attanasio | Runner-up | |

| New York Film Critics Circle[116][117] | Best Film | Quiz Show | Won |

| Best Supporting Actor | Paul Scofield | Runner-up | |

| Best Screenplay | Paul Attanasio | Runner-up | |

| Screen Actors Guild Award[118] | Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Supporting Role | John Turturro | Nominated |

Paul Scofield was also nominated for the Dallas–Fort Worth Film Critics Association Award for Best Supporting Actor, the National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Supporting Actor and the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Supporting Actor.

John Turturro was also nominated for the Chicago Film Critics Association Award for Best Supporting Actor.

References

editCitations

edit- ^ a b "All-Time Opening Weekends: 50 Screens or Less". Daily Variety. September 20, 1994. p. 24.

- ^ "Box Office Information for Quiz Show". Archived from the original on October 14, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Dunkel, Tom (September 27, 1994). "The Man with All the Answers". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved 2022-01-15.

- ^ a b "Quiz Show". Turner Classic Movies. Atlanta: Turner Broadcasting System (Time Warner). Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- ^ Goodwin, Richard N. (2014). Remembering America: A Voice from the Sixties (Paperback ed.). New York City: Open Road Integrated Media. ISBN 978-1497676572.

- ^ a b c d David Ansen (September 18, 1994). "When America Lost Its Innocence--Maybe". Newsweek.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (September 14, 1994). "QUIZ SHOW; Good and Evil in a More Innocent Age". The New York Times.

- ^ a b von Tunzelmann, Alex (December 14, 2012). "Quiz Show: Robert Redford's film gets all the answers right". The Guardian. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Turan, Kenneth (September 16, 1994). "Movie Review : 'Quiz Show's' Category: Evil and Moral Ambiguity". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ Greenfield, Meg (October 17, 1994). "The Quiz Show Scandals". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- ^ a b Auletta, Ken (September 19, 1994). "The $64,000 Question". The New Yorker. p. 48.

- ^ Twenty One (Game Show) Famous episode of December 5, 1956, 30 March 2020, retrieved 2023-09-27

- ^ a b Rosenbaum, Jonathan (7 September 1994). "Quiz Show". Chicago Reader. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Van Doren, Charles (July 28, 2008). "All The Answers". The New Yorker. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Eller, Claudia (August 7, 1994). "They're Naturals for 'Quiz Show'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Gelmis, Joseph (September 13, 1994). "An Icon With a Few Questions : Robert Redford's Personal Films Examine America's Merchant Mentality". Newsday. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c Hruska, Bronwen (August 28, 1994). "They Conned America". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Weinraub, Bernard (September 12, 1994). "Flawed Characters In the Public Eye, Past and Present". The New York Times. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ Rose 1994, 1:24–2:19.

- ^ Rose 1994, 3:25–3:58.

- ^ Wakefield, Dan (August 21, 1994). "His 50s, Then and Now.; Robert Redford". The New York Times. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- ^ Rose 1994, 4:59–5:17.

- ^ Rose 1994, 2:37–3:16.

- ^ Johnson, Ted (July 21, 2008). "Blast from the Past". Variety. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ a b "Entertainment news for May 14, 1993". Entertainment Weekly. May 14, 1993. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c Cawley, Janet (September 4, 1994). "Innocence was the Big Loser". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ Archerd, Army (May 6, 1993). "AMC sure it can lure out couch potatoes". Variety. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ Koltnow, Barry (September 23, 1994). "Rob Morrow Trades TV for Big-Screen Exposure". Orange County Register. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ Rose 1994, 5:43–5:52.

- ^ a b "Time Out". 8 February 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Newman, Kim (1995). "Quiz Show Review". Empire. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Wilmington, Michael (September 16, 1994). "Tarnishing the Golden Age". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (September 16, 1994). "Redford's 'Quiz Show' Raises All the Right Questions". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Levy, Emanuel (July 27, 2007). "Quiz Show (1994): Redford's Compelling Drama of TV Twenty-One Scandal, Starring Ralph Fiennes". EmanuelLevy.com. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Royko, Mike (September 23, 1994). "Movie Critics' View from Isolation Booth". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Stack, Peter (April 21, 1995). "Dark Days of a TV 'Quiz Show'". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "Quiz Show". TV Guide. Archived from the original on October 29, 2000. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Dutka, Elaine (October 7, 1993). "Levinson on Hollywood: The People on the Fringe". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ "Studios Ponder Perils, Payoffs Of Platforming". Variety. 16 January 1995. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ Quiz Show at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- ^ "Film Box Office Report". Daily Variety. September 20, 1994. p. 8.

- ^ "Quiz Show (1994)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ^ "Full 'House' 'Bunch' Slips 'Just' OK". Variety. 13 March 1995. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ Molner, David (January 22, 1995). "Berlin Boasts 19 World Bows". Variety. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ "China opens its doors to Sundance fest". Variety. October 9, 1995. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ Molner, David (February 19, 1995). "'Kiss' Seduces Berlin, Stirring Sluggish Mood". Variety. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ Groves, Dan (February 26, 1995). "'Quiz' Shows Spotty B.O. Overseas". Variety. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ "O'seas B.O. Is 'Terminal'". Variety. February 12, 1995. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ "Worldwide rentals beat domestic take". Variety. February 13, 1995. p. 28.

=International gross 1994: $1.5m

- ^ Klady, Leonard (February 19, 1996). "B.O. with a vengeance: $9.1 billion worldwide". Variety. p. 1.

International gross 1995: $25.9m

- ^ "Quiz Show, Rotten Tomatoes". Rottentomatoes.com. Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ Roger Ebert. "Quiz Show". September 16, 1994.

- ^ James Berardinelli. "Quiz Show". ReelViews.

- ^ Owen Gleiberman. "Quiz Show", Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ Van Doren, Charles (July 28, 2008). "All the Answers". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on June 8, 2021.

- ^ Vadeboncoeur, Joan (January 8, 1995). "Critically Acclaimed Best Movies of '94 Include Works from Tarantino, Burton, Demme, Redford, Disney and Speilberg". Syracuse Herald American (Final ed.). p. 16.

- ^ Hurley, John (December 30, 1994). "Movie Industry Hit Highs and Lows in '94". Staten Island Advance. p. D11.

- ^ Travers, Peter (December 29, 1994). "The Best and Worst Movies of 1994". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ P. Means, Sean (January 1, 1995). "'Pulp and Circumstance' After the Rise of Quentin Tarantino, Hollywood Would Never Be the Same". The Salt Lake Tribune (Final ed.). p. E1.

- ^ Kopp, Craig (December 29, 1994). "OUR CRITIC'S PICKS '94's winners: from 'Clerks' to 'Pulp Fiction'". The Cincinnati Post (Metro ed.). p. 3.

- ^ Lawson, Terry (December 25, 1994). "UNKNOWN QUALITIES Best Yet to Come Among Years Top 10 Movies". Dayton Daily News (City ed.). p. 3C.

- ^ Denerstein, Robert (January 1, 1995). "Perhaps It Was Best to Simply Fade to Black". Rocky Mountain News (Final ed.). p. 61A.

- ^ Schuldt, Scott (January 1, 1995). "Oklahoman Movie Critics Rank Their Favorites for the Year Without a Doubt, Blue Ribbon Goes to "Pulp Fiction," Scott Says". The Oklahoman. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ "Awards for 1994". National Board of Review. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (December 25, 1994). "1994: YEAR IN REVIEW : No Weddings, No Lions, No Gumps". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (December 27, 1994). "CRITIC'S NOTEBOOK; The Good, Bad and In-Between In a Year of Surprises on Film". The New York Times. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ Howe, Desson (December 30, 1994), "The Envelope Please: Reel Winners and Losers of 1994", The Washington Post, retrieved July 19, 2020

- ^ Hunter, Stephen (December 25, 1994). "Films worthy of the title 'best' in short supply MOVIES". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ Stupich, David (January 19, 1995). "Even with gore, 'Pulp Fiction' was film experience of the year". The Milwaukee Journal. p. 3.

- ^ Mills, Michael (December 30, 1994). "It's a Fact: 'Pulp Fiction' Year's Best". The Palm Beach Post (Final ed.). p. 7.

- ^ Davis, Sandi (January 1, 1995). "Oklahoman Movie Critics Rank Their Favorites for the Year "Forrest Gump" The Very Best, Sandi Declares". The Oklahoman. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ Vincent, Mal (January 7, 1995). "Mal's 10 Best Movies of '94". The Virginian-Pilot (Final ed.). p. E1.

- ^ Persall, Steve (December 30, 1994). "Fiction': The art of filmmaking". St. Petersburg Times (City ed.). p. 8.

- ^ Sheid, Christopher (December 30, 1994). "A year in review: Movies". The Munster Times.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (December 25, 1994). "The Year's Best Movies". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ MacCambridge, Michael (December 22, 1994). "it's a LOVE-HATE thing". Austin American-Statesman (Final ed.). p. 38.

- ^ Strauss, Bob (December 30, 1994). "At the Movies: Quantity Over Quality". Los Angeles Daily News (Valley ed.). p. L6.

- ^ Armstrong, Douglas (January 1, 1995). "End-of-year slump is not a happy ending". The Milwaukee Journal. p. 2.

- ^ Roberts, Jerry (December 30, 1994). "What kind of a movie year was it? It was mainly the pits Tom Hanks played "Forrest Gump" in one of the year's best". Daily Breeze. p. K12.

- ^ Rahr, David (December 30, 1994). "Tarantino Top's Rahr's List". The Santa Fe New Mexican. p. 37.

- ^ Bates, Mack (January 19, 1995). "Originality of 'Hoop Dreams' makes it the movie of the year". The Milwaukee Journal. p. 3.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 31, 1994). "The Best 10 Movies of 1994". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ Berardinelli, James (January 2, 1995). "Rewinding 1994 -- The Year in Film". ReelViews. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ Dudek, Duane (December 30, 1994). "1994 was a year of slim pickings". Milwaukee Sentinel. p. 3.

- ^ Webster, Dan (January 1, 1995). "In Year of Disappointments, Some Movies Still Delivered". The Spokesman-Review (Spokane ed.). p. 2.

- ^ Clark, Mike (December 28, 1994). "Scoring with true life, 'True Lies' and 'Fiction.'". USA Today (Final ed.). p. 5D.

- ^ Arnold, William (December 30, 1994). "'94 Movies: Best and Worst". Seattle Post-Intelligencer (Final ed.). p. 20.

- ^ Zoller Seitz, Matt (January 12, 1995). "Personal best From a year full of startling and memorable movies, here are our favorites". Dallas Observer.

- ^ a b "The Year's Best". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. December 25, 1994. p. K/1.

- ^ Simon, Jeff (January 1, 1995). "Movies: Once More, with Feeling". The Buffalo News. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ Ross, Bob (December 30, 1994). "1994 The Year in Entertainment". The Tampa Tribune (Final ed.). p. 18.

- ^ Harrison, Eric (January 8, 1995). "Movie Magic". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. p. 1E.

- ^ Mayo, Mike (December 30, 1994). "The Hits and Misses at the Movies in '94". The Roanoke Times (Metro ed.). p. 1.

- ^ Pickle, Betsy (December 30, 1994). "Searching for the Top 10... Whenever They May Be". Knoxville News-Sentinel. p. 3.

- ^ Carlton, Bob (December 29, 1994). "It Was a Good Year at Movies". The Birmingham News. p. 12-01.

- ^ Delmont, Jim; Minge, Jim (December 30, 1994). "A Critical Look Back 'Gump,' 'Little Women' Among Top Films of '94 Can You Still See Them?". Omaha World-Herald (Sunrise ed.). p. 31sf.

- ^ Movshovitz, Howie (December 25, 1994). "Memorable Movies of '94 Independents, fringes filled out a lean year". The Denver Post (Rockies ed.). p. E-1.

- ^ Meyer, George (December 30, 1994). "The Year of the Middling Movie". The Ledger. p. 6TO.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (January 1, 1995). "Film". The Washington Times (2 ed.). p. D3.

- ^ Craft, Dan (December 30, 1994). "Success, Failure and a Lot of In-between; Movies '94". The Pantagraph. p. B1.

- ^ Lyons, Jeffrey (host); Medved, Michael (host) (January 6, 1995). "Best & Worst of 1994". Sneak Previews. Season 20. WTTW. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ Lovell, Glenn (December 25, 1994). "The Past Picture Show the Good, the Bad and the Ugly -- a Year Worth's of Movie Memories". San Jose Mercury News (Morning Final ed.). p. 3.

- ^ King, Dennis (December 25, 1994). "SCREEN SAVERS In a Year of Faulty Epics, The Oddest Little Movies Made The Biggest Impact". Tulsa World (Final Home ed.). p. E1.

- ^ Elliott, David (December 25, 1994). "On the big screen, color it a satisfying time". The San Diego Union-Tribune (1, 2 ed.). p. E=8.

- ^ "2015 Nominees – 6th Annual 20/20 Awards". 20/20 Awards. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ "The 67th Academy Awards (1994) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. 4 October 2014. Retrieved June 6, 2018.

- ^ "ACCA 1994". Awards Circuit. 2014. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ Carr, Jay (December 19, 1994). "Boston critics pick 'Pulp' as top film". The Boston Globe. p. 59.

- ^ Dawtrey, Adam (February 19, 1995). "'Weddings' Waltzes With 11 BAFTA Noms". Variety. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ "British film & TV acad toasts 'Weddings' with five nods". Variety. May 1, 1995. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ Cox, Dan (January 29, 1995). "New Faces, Practiced Hands". Variety. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ "Quiz Show". Golden Globe Awards. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ "PGA Film Noms Mirror DGA Pix". Variety. January 29, 1995. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ Carr, Jay (January 5, 1995). "'Pulp Fiction' Wins Critics' Nod". Seattle Post-Intelligencer (Final ed.). p. C5.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (December 16, 1994). "Critics Honor 'Pulp Fiction' And 'Quiz Show'". The New York Times. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ "New York Film Critics Circle – Year 1994". FilmAffinity. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ "The Inaugural Screen Actors Guild Awards". SAG Awards. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

Videos

edit- Rose, Charlie (September 13, 1994). Paul Attanasio. Charlie Rose (Talk show interview). Retrieved July 20, 2020.

External links

edit- Quiz Show at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Quiz Show at IMDb

- Quiz Show at the TCM Movie Database

- Quiz Show at Rotten Tomatoes